Anne Askew and Her “Brothers”

by Kathy Simcox

Over the years I’ve developed a passion for the English Reformation. Although, until two years ago, I never knew England actually had a Reformation of its own. Being Lutheran, I knew all about Martin Luther and his 95 Theses of 1517 and a tiny clue as to who Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I all were. But I didn’t know the impact of Luther’s ideas on the wider world, England’s world in particular. During a recent trip to England, armed with an appropriate amount of knowledge, I toured from Devon and Cornwall, to London and Kent and came face-to-face with many of the English Reformation sites, including sites dedicated to many of the martyrs, both Catholic and Protestant, executed for their beliefs.

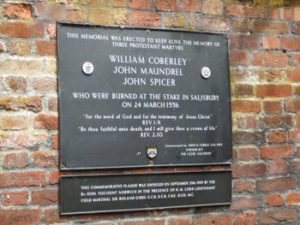

In the town of Salisbury, home of the famous Salisbury Cathedral, three Protestant martyrs were burned in 1156. One of them because he called the Pope an Antichrist. At Oxford University, the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer, Bishop Hugh Latirmer and clergyman Nicolas Ridley were all accused of heresy in 155 and burned at the entrance gate of Balliol College. It is said the gate still bears the scorch marks.

In the town of Salisbury, home of the famous Salisbury Cathedral, three Protestant martyrs were burned in 1156. One of them because he called the Pope an Antichrist. At Oxford University, the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer, Bishop Hugh Latirmer and clergyman Nicolas Ridley were all accused of heresy in 155 and burned at the entrance gate of Balliol College. It is said the gate still bears the scorch marks.

The English Reformation can go down in history as one of the bloodiest events in England’s history. Hundreds of Christians lost their lives during this upheaval in the 16th century. Almost 300 Protestants were executed during the five-year reign of “Bloody” Mary I and throughout the English Reformation 350 Catholics suffered the same fate, many under Elizabeth I.

Between 1535 and 1681, over a hundred Catholics were executed at Tyburn Convent, located at the northeastern corner of Hyde Park in London. This was the site of The King’s Gallows for six centuries. Those accused of treason were hung, drawn and quartered here. John Houghton, a Carthusian Prior, was the first Catholic to be hanged at Tyburn. He was sent to the rope in 1535 because he refused to acknowledge the supremacy of Henry VIII over the Church of England. Another martyr, a Catholic priest named Ralph Sherwin, was accused of conspiring to murder Queen Elizabeth I and sentenced to hang in 1581.

In the shadow of St. Paul’s Cathedral, situated at the intersection of Little Britain and West Smithfield is Smithfield, a livestock market dating back 800 years, one of the oldest markets in London. The area was once known as the execution site for 50 Protestants who met their end by fire. I visited Smithfield the first Sunday of my London journey. It was eerily quiet that morning, barely a person about, so I was able to absorb the historical immensity of the place, a truly emotional experience.

In the shadow of St. Paul’s Cathedral, situated at the intersection of Little Britain and West Smithfield is Smithfield, a livestock market dating back 800 years, one of the oldest markets in London. The area was once known as the execution site for 50 Protestants who met their end by fire. I visited Smithfield the first Sunday of my London journey. It was eerily quiet that morning, barely a person about, so I was able to absorb the historical immensity of the place, a truly emotional experience.

Across the street from Smithfield Market, embedded in the wall of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, is a plaque dedicated to these martyrs. Three are named: John Rogers, who became a Protestant after meeting the author of the first English translation of the New Testament, William Tyndale, in Antwerp; John Philpot, Archdeacon of Winchester; and John Bradford, prebend of St. Paul’s church. These men met their fate in the mid 1500’s while Bloody Mary occupied the throne.

Across the street from Smithfield Market, embedded in the wall of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, is a plaque dedicated to these martyrs. Three are named: John Rogers, who became a Protestant after meeting the author of the first English translation of the New Testament, William Tyndale, in Antwerp; John Philpot, Archdeacon of Winchester; and John Bradford, prebend of St. Paul’s church. These men met their fate in the mid 1500’s while Bloody Mary occupied the throne.

All of these martyrs, both Catholic and Protestant, deserve to have their stories told. But one young woman in particular has mysteriously captured my heart has mysteriously captured my heart: Anne Askew. For her tragic tale, we must first go back to the events that triggered the English Reformation.

Henry VIII (1509 – 1547) was a Catholic and remained so throughout his life. He loved the ceremonies, the structure and the traditions of the Catholic Church, and considered Martin Luther a heretic. For this he was called Fidei Defensor, or “Defender of the Faith” in England. However, as much as Henry hated Luther, he hated the Pope even more. This was the result of his desire to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon and the church’s harsh reaction toward it. As king, one of his responsibilities to his people was to secure the throne with a male heir. His marriage to Catherine had produced the future Queen Mary. This was a problem as women heirs to the throne were highly frowned upon. Out of frustration he sought the help of his cardinal and favorite, Thomas Wolsey. Wolsey was sent on a mission to Rome to appeal for Henry’s divorce. The Pope wouldn’t hear of it and so just as quickly as the “Great Cardinal” came into favor with Henry, he fell right back out again. Another, Thomas Cromwell, replaced him.

Cromwell had Protestant sympathies. Thanks to the advent of the printing press, Luther’s ideas were being spread throughout the western world. Parliament was already pushing for church reform and reform ideas were being talked about in many educational centers like Oxford. Between the years 1529 and 1536, Henry held seven parliaments, during which Henry was declared the Supreme Head of Church and State in England, granting him freedom to do whatever he pleased with his marriage to Catherine giving him freedom to marry Anne Boleyn, in hopes of producing a male heir. “The King’s Great Matter”, as Henry’s divorce issues were known, and all of the changes brought about by it, prepared England for her long and bloody journey toward Protestantism.

Cromwell had Protestant sympathies. Thanks to the advent of the printing press, Luther’s ideas were being spread throughout the western world. Parliament was already pushing for church reform and reform ideas were being talked about in many educational centers like Oxford. Between the years 1529 and 1536, Henry held seven parliaments, during which Henry was declared the Supreme Head of Church and State in England, granting him freedom to do whatever he pleased with his marriage to Catherine giving him freedom to marry Anne Boleyn, in hopes of producing a male heir. “The King’s Great Matter”, as Henry’s divorce issues were known, and all of the changes brought about by it, prepared England for her long and bloody journey toward Protestantism.

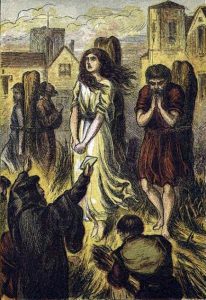

All of these activities wouldn’t go unnoticed by a 25-year-old poet and preacher from Lincolnshire. Anne Askew was born of a noble family in 1521 and forced into and unhappy marriage at the tender age of 15. Anne not only rebelled against her husband by refusing his surname, she rebelled against his Catholic beliefs as well. Her strong Protestant convictions caused her husband to throw her out of the home. She left him and their two children and traveled to London to preach against the doctrine of transubstantiation (the literal presence of Christ’s body and blood at the Eucharist) and to distribute Protestant literature. She had connections with ladies at Queen Catherine Parr’s Protestant court, but even threatened with torture she wouldn’t reveal any names as to do so would mean their downfall, including the queen’s herself.

These acts landed Anne in the Tower of London, charged with heresy. She was tortured on the Rack so badly that when it came time for her execution at Smithfield in 1546, she had to be carried to the scaffold on a chair since she was unable to walk. She could still write, however, and wrote many letters from prison, including a hymn that resonates with a maturity and depth of faith well beyond her 25 years. The first stanza reads:

These acts landed Anne in the Tower of London, charged with heresy. She was tortured on the Rack so badly that when it came time for her execution at Smithfield in 1546, she had to be carried to the scaffold on a chair since she was unable to walk. She could still write, however, and wrote many letters from prison, including a hymn that resonates with a maturity and depth of faith well beyond her 25 years. The first stanza reads:

“Like an armed knight appointed to the field, with this world I will fight and Faith shall be my shield.”

She also wrote a first-person account of her ordeal, published in John Bale’s Examinations and later in John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments of these Latter and Perilous Days, touching Matters of the Church (Foxe’s Book of Martyrs) in 1563.

I had read only a few things about Anne Askew and though I knew who she was and the reason she died, I didn’t really consider anything more about her other than her trial and execution at Smithfield. In fact, she was the main reason I penciled Smithfield into my itinerary in the first place. So imagine my surprise when, as I explored the inside the Bloody Tower at the Tower of London, I walked right into her cell. I had just visited the room where the Rack and other replicas of torture instruments were being displayed. As I climbed up the steps I noticed a tiny, yet intriguing room and ventured inside and glanced around. The room was about five feet by five feet and barely ten feet high with one arched window embedded in the wall. As I turned back toward the doorway, I saw something that made my heart skip a beat: a large plaque attached to the cold stone explaining the life and death of Anne Askew. I stood in her cell riveted to the spot for several minutes, overcome with emotion, trying to feel her presence. I tried to imagine how she would have felt knowing she was about to die for her beliefs and wondered how someone so young could have such strength of conviction.

I had read only a few things about Anne Askew and though I knew who she was and the reason she died, I didn’t really consider anything more about her other than her trial and execution at Smithfield. In fact, she was the main reason I penciled Smithfield into my itinerary in the first place. So imagine my surprise when, as I explored the inside the Bloody Tower at the Tower of London, I walked right into her cell. I had just visited the room where the Rack and other replicas of torture instruments were being displayed. As I climbed up the steps I noticed a tiny, yet intriguing room and ventured inside and glanced around. The room was about five feet by five feet and barely ten feet high with one arched window embedded in the wall. As I turned back toward the doorway, I saw something that made my heart skip a beat: a large plaque attached to the cold stone explaining the life and death of Anne Askew. I stood in her cell riveted to the spot for several minutes, overcome with emotion, trying to feel her presence. I tried to imagine how she would have felt knowing she was about to die for her beliefs and wondered how someone so young could have such strength of conviction.

I’ve always thought that a divine spirit guides us to places unknown when we least expect it to. I truly had no clue what I had stumbled upon that day but looking back on it now, there’s no doubt in my mind what led me to Anne’s special place in Tower history.

I walked back outside in a daze, not quite understanding what had happened or how everything I had experienced came to be. It wasn’t until later that I realized that that ever-present divine hand was guiding me to that room, and that I was guided there in order to tell Anne’s story to others.

Why was I so taken by her story? Perhaps it’s because I share her Protestant faith. Or perhaps my own cowardice reveres someone so young who was willing to sacrifice so much for her beliefs. Would I be so brave?

The stories of all the English martyrs are stories worth being told, for as the years dwindle, so too does history’s memory. The events that shaped the lives of the 16th century martyrs also shaped the world we live in today, and they are events, and lives, too important to forget.

Tower of London Tours Now Available:

Private Guided Tour: Tower of London

Tower of London Entrance Ticket Including Crown Jewels and Beefeater Tour

Royal London Walking Tour Including Early Access to the Tower of London and Changing of The Guard

London Super Saver: London City Sightseeing Including Tower of London plus Jack the Ripper and Ghost Walking Tour

Further Information:

For more about Anne Askew:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anne_Askew

The Tower of London:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tower_of_London

Smithfield Market:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smithfield_London

About the author:

Kathy Simcox lives in Columbus, Ohio. Ms. Simcox is an office manager at the College of the Arts at Ohio State University. She has a BA in psychology from Ohio University and has recently graduated from Ohio State with a 2nd B.A. in Religious Studies. She is active in her church, singing in the music program. She enjoys traveling, writing, kayaking, hiking, biking, cross country skiing, swimming, Irish music, British comedies, and Guinness. She is also known to pick up an occasional book, preferably historical fiction. Some of her pictures can be viewed at: community.webshots.com/user/kayakgirl41 Contact: itravellen@shaw.ca

Image credits:

All photos by Kathy Simcox

Tower of London engraving: Nathaniel Buck, Samuel Buck / Public domain

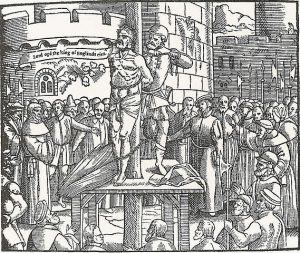

Woodcut of Preparations to burn the body of William Tyndale: John Foxe / Public domain

Martyrdom of Anne Askew illustration: Unknown author / Public domain