A Fusion of Frontier Cultures

by Victor A. Walsh

Shafts of early morning light flit across the two-lane paved road like an illusion. The rolling hills of the Santa Cruz Valley are painted in tones of eerie gray. Shadows linger in the ravines.

We arrive at the ruin of Mission San José de Tumacácori (Too muh ka KO re) off Arizona Highway 19 by 7:30 a.m., a half-hour before it opens. Everything is closed, including the restaurant and tourist shops across the street.

The rising light shimmers off the large mesquite trees creating spider webs of shadows out of their twisted gnarled branches. The top of the yellow stucco enclosure wall seems to glow in the warm light. I wonder if what I’m seeing is a momentary illusion of Tumacácori’s shattered past. Founded in 1691 by the intrepid Jesuit missionary and explorer, Fr. Eusebio Francisco Kino, the original mission would serve as the northern most outpost of Spanish Christendom in Arizona for over a century against near insufferable odds of struggle among different cultures in harsh desert conditions.

My friend Dick and I wait patiently, watching two big black crows circling overhead. At 8 a.m., we enter. The grounds are empty. The mission church, which was built between 1800 and 1823, stands on the far side of a barren field as it probably looked in 1908 when President Theodore Roosevelt declared Tumacácori a national monument. The massive bell tower and kiln-fired adobe brick walls stand obliquely, silently in the morning light. Time has stopped here as if inhabited by the ghosts, by dreams somehow gone astray.

My friend Dick and I wait patiently, watching two big black crows circling overhead. At 8 a.m., we enter. The grounds are empty. The mission church, which was built between 1800 and 1823, stands on the far side of a barren field as it probably looked in 1908 when President Theodore Roosevelt declared Tumacácori a national monument. The massive bell tower and kiln-fired adobe brick walls stand obliquely, silently in the morning light. Time has stopped here as if inhabited by the ghosts, by dreams somehow gone astray.

In the garden we meet our guide Wally Mohr, an effusive retiree brimming with ideas. He tells us that the mission was originally founded on the site of a Pima or Akimel O’odham Indian village on the opposite (east) bank of the Santa Cruz River. “Tumacácori is a Spanish phonetic translation of the O’odham name for their village,” he says. “It probably means ‘rocky flat place.’”

In the garden we meet our guide Wally Mohr, an effusive retiree brimming with ideas. He tells us that the mission was originally founded on the site of a Pima or Akimel O’odham Indian village on the opposite (east) bank of the Santa Cruz River. “Tumacácori is a Spanish phonetic translation of the O’odham name for their village,” he says. “It probably means ‘rocky flat place.’”

The Akimel O’odham, we learn, invited Kino to visit them. “He made Tumacácori into a year-round, self-sustaining community by bringing livestock and fruit trees to the O’odham,” says Wally, pointing at a small pomegranate and apricot tree in the garden. “He learned their language, and treated them with great respect. Unlike most missions, there was no forced conversion here.”

We walk inside to the room with a model of the mission as it probably looked in the early 19th century. Along with the church, it features housing for the O’odham converts, numerous workshops, an irrigation system, a school, granary, cemetery and mortuary chapel, gardens, orchards and fields of beans, squash and corn.

We walk inside to the room with a model of the mission as it probably looked in the early 19th century. Along with the church, it features housing for the O’odham converts, numerous workshops, an irrigation system, a school, granary, cemetery and mortuary chapel, gardens, orchards and fields of beans, squash and corn.

Spanish Catholic devotions and practices were not fundamentally different from the traditional polytheistic beliefs of the O’odham. “When the Jesuits arrived, they brought even more Gods, only called saints. They had the cross, the statues of the saints, the holy water—all symbols of divine presence and intercession,” explains Wally. “The O’odham have a creation story like Noah’s Ark in which a great flood destroyed all the evil people. Their God, I’itoi, who led the first people out of the Underworld, is the equivalent of Jesus Christ.”

Once outside, I stare again at the church’s pale brown adobe façade decorated with a rich fretwork of pilasters and curved and pointed arches and a lofty redbrick bell tower. Big swaths of white lime plaster cling to the wall. Some of the original paint is still visible under the cornice below the main window. In its day this frontier church must have been a dazzling spectacle of color and architectural elegance; in fact, it still is — a testament to a steadfast communal faith that seems sadly out of step in modern society.

Once outside, I stare again at the church’s pale brown adobe façade decorated with a rich fretwork of pilasters and curved and pointed arches and a lofty redbrick bell tower. Big swaths of white lime plaster cling to the wall. Some of the original paint is still visible under the cornice below the main window. In its day this frontier church must have been a dazzling spectacle of color and architectural elegance; in fact, it still is — a testament to a steadfast communal faith that seems sadly out of step in modern society.

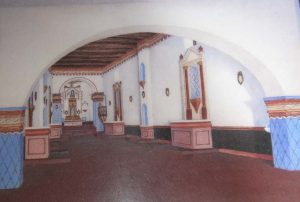

The interior is even more colorful. The lime-plaster walls of the nave are embedded with crushed red brick and decorated with Mexican baroque statuary and carvings of the Stations of the Cross. The walls surrounding the altar and the towering domed ceiling above it are still adorned with traces of the original painted and stenciled devotional imagery. The flickering candles, mosaic of color and images, and sound of choir voices echoing throughout the great hall must have brought tranquility to parishioners, Indian and non-Indian alike. The bonds of faith, born from a higher spiritual purpose, kept them together.

The church regrettably was never completed, stymied by the intractable forces of history. The struggle for Mexican independence from Spain brought chaos to the region and neglect of the missions. Apache raids once again devastated the Santa Cruz Valley. Funds for construction were meager, and epidemics of smallpox took a frightful toll among the children — so great that a new cemetery was created for their internment in 1822. Six years later Tumacácori lost its last resident priest when the Mexican government ordered all Spanish-born residents to leave the country.

Indian converts and a few settlers with the aid of visiting Mexican priests held on for another two decades. During the war against the United States, Mexico could neither defend nor supply the beleaguered mission. Lieutenant Cave Johnson Couts on his way back with U.S. troops from the 1847 campaign in Mexico noted in his journal:

At Tumacácori is a very large and fine church standing in the midst of a few conical Indian huts…This Church is now taken care of by the Indians….No priest has been in attendance for many years, though all its images, pictures, figures, etc. remain unmolested, and in good keeping.

Mounting Apache raids and a bitterly cold winter in 1848 finally drove out the last residents. They carried with them the church’s holy statues, chalices and priestly vestments to San Xavier del Bac, the Tohono O’odham Indian church near Tucson.

More than anywhere else, the cemetery enclosed by high adobe walls around the mortuary chapel tells the mission’s story. There is no trace of mission-era Indian graves – long ago destroyed by weather, treasure hunters, and cattlemen who used the cemetery as a corral. Around 1900, Indian families, who remembered Tumacácori’s past, began to bury their dead once again on this holy ground – campo santo.

Mounds of rocks and old wooden crosses mark the gravesites. A few of them have bouquets of artificial flowers. There are no names; just stillness as the branches of two old mesquites cast a quilt work of zigzag shadows across an adobe wall.

If You Go:

Getting There:

- Tumacácori National Historical Park is located off of Exit 29 of Interstate 19, forty-five miles south of Tucson, Arizona, and nineteen miles north of Nogales, Arizona. The park is open every day except Thanksgiving and Christmas from 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.

Getting Around:

- The best way to get to Tumacácori is by care, although buses, shuttles and taxis are available in nearby towns, along with renting bicycles.

History and Attractions:

- In 1990, Congress designated Tumacácori a national historical park. The re-designation included the mission ruins of nearby Los Santos Ángeles de Guevavi and San Cayetano de Calabazas. These ruins are not open to the public, but can be visited during the winter months as part of scheduled reserved tours.

- The National Park Service’s mandate is to preserve the mission ruins. After residents left in 1848, the mission deteriorated. Its current appearance reflects this historical circumstance.

- The mission hosts a variety of special events, including Day of the Dead festivities on November 2nd and the popular La Fiesta de Tumacácori during the first weekend in December.

- The Cathedral of San Xavier del Bac, located just south of Tucson off I-19, is perhaps the finest example of Spanish colonial architecture in the United States. It is a living parish community, the mother church of the Tohono O’odham (the Desert People).

- Located just north of Tumacácori on I-19, Tubac Presidio State Historic Park is a quiet enclave that evokes a bygone era. The park includes the 1752 presidio footprint, an excellent museum, and an innovative underground archaeology display. The town itself has many antique and handicraft shops around the main square.

- Best time to visit the Santa Cruz Valley is during summer when many rural border towns hold celebrations such as the Día de San Juan and the Fíesta de San Agustín, two festivals with roots extending back to the Catholic Spanish era.

Accommodations:

- Santa Cruz County is a major hub of tourism and different types of accommodations from expensive resorts to lodges, inns, motels and B&Bs are available in nearby towns like Green Valley, Amado, Tubac, Rio Rico and Nogales. Camping is available at the U.S. Forest Service’s Bog Springs and White Rock Campgrounds and RV parks exist off I-19 in Amado and on Route 82 twelve miles east of Nogales.

For More Information:

- Contact Tumacácori National Historical Park, P.O. Box 67, Tumacácori, AZ 85640, (520) 398-2341.

About the author:

Victor A. Walsh spends his time when he’s productively unemployed prowling forgotten or unusual destinations looking for stories that connect a place and its people to their remembered past. His historical essays and travel stories have appeared in the Christian Science Monitor, American History, Literary Traveler, California History, Rosebud and Sunset, among other publications.

Photos by by Richard Miller and Victor A. Walsh.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.