Haworth, West Yorkshire

by M.L. Gordon

I came to Haworth, as many do, in search of ghosts. Not necessarily the kind that come rapping at your window in the night (although those would have been fine, too), but the kind that beget inspiration and satisfy that inexplicable craving to connect to those whose words we cherish. I came, in the words of Virginia Woolf, “as though [I were] to meet some long-separated friend, who might have changed in the interval—so clear an image of Haworth had [I] from print and picture.” The parsonage was a shrine; its past inhabitants, ethereal, visionary beings. I came with expectations.

I shuddered into the station at Haworth in style aboard a beautifully restored Keighley and Worth Valley Railway steam train. My guidebook said I could have taken a bus, but I sought a more authentic Brontë experience. That said, I don’t know what I expected to be greeted by upon my arrival in town (a glowering Rochester in front of Thornfield, perhaps?) but this was certainly not it. Oh, sure—I could see the muted browns and purples of the moors in the distance, and a cold drizzle gave luster to the cobblestones—but Haworth Tandoori? Had I come this far to imagine the three sisters walking arm in arm off the moors and onto the cobbled street to stop for the best curry take-away this side of Bombay before they went home to write their masterpieces? “Mmm, Anne, you’ve got to try their chicken tikka!” This I was not prepared for. Welcome to Brontë Country.

I shuddered into the station at Haworth in style aboard a beautifully restored Keighley and Worth Valley Railway steam train. My guidebook said I could have taken a bus, but I sought a more authentic Brontë experience. That said, I don’t know what I expected to be greeted by upon my arrival in town (a glowering Rochester in front of Thornfield, perhaps?) but this was certainly not it. Oh, sure—I could see the muted browns and purples of the moors in the distance, and a cold drizzle gave luster to the cobblestones—but Haworth Tandoori? Had I come this far to imagine the three sisters walking arm in arm off the moors and onto the cobbled street to stop for the best curry take-away this side of Bombay before they went home to write their masterpieces? “Mmm, Anne, you’ve got to try their chicken tikka!” This I was not prepared for. Welcome to Brontë Country.

“I do not know whether pilgrimages to the shrines of famous men ought not to be condemned as sentimental journeys,” wrote Woolf in the same essay about her 1904 trip to Haworth. I have to agree. It wasn’t as though the Brontës themselves hadn’t tried to warn me. Haworth, appearing in an assortment of forms throughout their juvenilia, is a sadly ordinary place. And I soon realized the only ghosts it might manifest for me were those of my own naive imagining.

Just beyond the Black Bull Inn (which, if legend is to be believed, is where Branwell Brontë drank himself into oblivion) is the hill leading to Haworth Parsonage and the Church of St. Michael and All Angels, where much of the family is buried. Dodging raindrops, I set out to pay my respects.

Just beyond the Black Bull Inn (which, if legend is to be believed, is where Branwell Brontë drank himself into oblivion) is the hill leading to Haworth Parsonage and the Church of St. Michael and All Angels, where much of the family is buried. Dodging raindrops, I set out to pay my respects.

The existing church was built just over 100 years ago; only the tower would have been familiar to the Brontës. It is a very ordinary church by any standard in spite of its housing such relics as a Brontë family Bible and Charlotte’s 1854 marriage certificate to Arthur Bell Nicholls, her father’s curate. A simple monument marks the location of the family vault: no statues, no ostentatious bouquets, no velvet ropes. Little distinguishes it from any other memorial, in fact, aside from the quiet clusters of tourists. Together we paced by it over again as if to give it a second chance, puzzled, perhaps, that we weren’t more moved.

I took the street past the graveyard and to the door of the parsonage, all squat and dour in greys and browns. This was the family’s home from 1820 until the Reverend Patrick Brontë’s death in 1861. Having read several biographies of the family, many things were familiar to me—the clock that Reverend Brontë wound nightly, the bedroom where Branwell supposedly set his bedclothes ablaze in a drunken stupor, the cozy clutter of pots and pans in the kitchen where Emily often studied even as she baked or helped Tabby with “pilling a potate,” as her diary fragment put it. Here were created some of the most enduring works of the English language by the three sisters who shared stories during nightly walks in the dining room. Their windows overlooked the moors and the graveyard, already full in their day, and it is not hard to imagine the genesis of these dark tales. I still expected to feel something of this as I moved from room to room, looking at the unexceptional, everyday items that had outlasted their owners.

I took the street past the graveyard and to the door of the parsonage, all squat and dour in greys and browns. This was the family’s home from 1820 until the Reverend Patrick Brontë’s death in 1861. Having read several biographies of the family, many things were familiar to me—the clock that Reverend Brontë wound nightly, the bedroom where Branwell supposedly set his bedclothes ablaze in a drunken stupor, the cozy clutter of pots and pans in the kitchen where Emily often studied even as she baked or helped Tabby with “pilling a potate,” as her diary fragment put it. Here were created some of the most enduring works of the English language by the three sisters who shared stories during nightly walks in the dining room. Their windows overlooked the moors and the graveyard, already full in their day, and it is not hard to imagine the genesis of these dark tales. I still expected to feel something of this as I moved from room to room, looking at the unexceptional, everyday items that had outlasted their owners.

“You can get one of them sampler patterns in the gift shop, dearie,” an old woman next to me said, patting me on the arm as we shuffled past a case of Brontë needlework.

Where was the gloom? The oppressive sense of genius and promise unfulfilled? The last traces of their otherworldly ingenuity? I sure wasn’t going to find it in the family chamber pot.

I paused for a moment in the narrow children’s study, made even smaller by Charlotte’s expansions after her sisters’ deaths. Surely this, the room in which a box of wooden soldiers had served as the origin of stories that would later evolve into Jane Eyre, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Wuthering Heights, would bring me the epiphany I craved.

I looked out the window at the graveyard below, struck by its size. Tens of thousands of gravestones jutted out at awkward angles under a canopy of trees, and I thought of how commonplace death was in the world of the Brontës. The children had lost their mother and two older sisters before Charlotte, the next eldest, was ten. And her three younger siblings—Branwell, Emily and Anne—all died young within mere months of each other. Charlotte herself died in the early stages of pregnancy before the age of forty. Just before I had the chance to wax pensive over the tragedy of the Bronte family, a line of uniformed schoolchildren snaked wildly through the grey monuments in the graveyard below. A few brave souls climbed atop the stones and shrieked with laughter as teachers pulled them down, avoiding the eyes of indignant onlookers. No ghosts here. I sighed, and decided to head for the moors.

I looked out the window at the graveyard below, struck by its size. Tens of thousands of gravestones jutted out at awkward angles under a canopy of trees, and I thought of how commonplace death was in the world of the Brontës. The children had lost their mother and two older sisters before Charlotte, the next eldest, was ten. And her three younger siblings—Branwell, Emily and Anne—all died young within mere months of each other. Charlotte herself died in the early stages of pregnancy before the age of forty. Just before I had the chance to wax pensive over the tragedy of the Bronte family, a line of uniformed schoolchildren snaked wildly through the grey monuments in the graveyard below. A few brave souls climbed atop the stones and shrieked with laughter as teachers pulled them down, avoiding the eyes of indignant onlookers. No ghosts here. I sighed, and decided to head for the moors.

I had dutifully shelled out a few pounds for the parsonage tour and followed the steady stream of tourists through the house and church, but a walk on the moors in wild weather was the sort of thing you couldn’t buy tickets for. Every fiber of my romantic being hungered for transcendence. A hint of evening already lurked in the rough hollows between the hills and rain – needle-sharp and nearly horizontal – pricked at my arms. I stumbled into the wind, half believing Heathcliff might be just over the next rise. He was not. Two local girls, gossiping and giggling as they skipped up the hill in jeans and bulky, damp sweaters, were. They politely indulged me by snapping my photograph next to an obliging sheep and headed in the direction of the village. As they passed, I could see on the horizon behind them Top Withens, which is the alleged original for Wuthering Heights (though it bears little resemblance to Emily’s description in the book). It was a wonderfully stark, lonely view, one I had enjoyed in various incarnations in the Brontës’ works. But the moment had been broken so many times before that I decided to leave it there – to run into a sign that gave directions to Top Withens in Japanese a few yards down the path would have spoiled it forever. I turned back, passed the parsonage, and headed towards the train station.

By the time I reached the churchyard, the downpour had subsided into an indifferent drizzle that darkened the tombstones and the church walls. I ducked inside for a last look. This time I found myself alone. Except for them. They were there, of course, all but Anne—the mother, the father, the aunt, the little sister-saints and their literary siblings that comprised three-fourths of the so-called “dark quartet.”

But for all of their romanticized Gothic appeal, and in spite of the dismal weather, I had to conclude that the day had been disappointingly devoid of spirits. The parsonage had made the “tragic” family hopelessly and quaintly corporeal, from the banality of the family’s washstand to the display of their nightshirts and caps. Any lingering desire I had to idealize the moors had been swept away by the shrill chatter of the young girls ambling over the path to the village. Even the church, pockmarks in the tower and all (supposedly from Mr. Brontë’s gun, which folklore says he discharged daily), cheerfully refused to be haunted.

And somehow I didn’t want it to be anymore. Gazing over the family monument tucked modestly under its pillar, I couldn’t help but wonder with Lockwood in Wuthering Heights “how any one could ever imagine unquiet slumbers for the sleepers in that quiet earth.”

Private Group Haworth, Bolton Abbey and Steam Trains Day Trip from York

If You Go:

Bronte Parsonage Museum

www.bronte.org.uk

Church Street

Haworth

Keighley

West Yorkshire

England

BD22 8DR

Open daily from 10.00am – 5.30pm April to September, 11.00am – 5.00pm October to March.

Standard admission £6.00

Senior Citizens £4.00

Students £4.00

Children 5-16 years £2.50

Children under 5 free

Family Ticket £15.00 (admits 2 adults and up to 3 children age 5 – 16 years)

About the author:

M.L. Gordon is a freelance writer and English teacher living in Phoenix, Arizona. Contact info: revas_m@yahoo.com

Photo credits:

Top Withins by Dave.Dunford Dave.Dunford / Public domain

Haworth railway station by: NRTurner / CC BY-SA

Black Bull Inn, Haworth by: Tim Green from Bradford / CC BY

Bronte Parsonage Museum view from graveyard by: Davekpcv / CC BY-SA

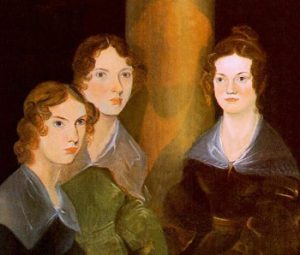

Brontë Sisters portrait by Patrick Branwell Brontë restored Branwell Brontë / Public domain