by Jason Templer

Doe-eyed and powder-faced, the girls march in single file through a wooden hula-hoop, flourishing their Muromachi-style kimonos as camera shots fill the air like a multitudinous flutter of pigeons. Sitting down to perform the rice dance, Reiko peers back at the throng of camera-toting tourists in a wizened look of innocence, as if disapproving the vain Instagram and twitter paparazzos.

Doe-eyed and powder-faced, the girls march in single file through a wooden hula-hoop, flourishing their Muromachi-style kimonos as camera shots fill the air like a multitudinous flutter of pigeons. Sitting down to perform the rice dance, Reiko peers back at the throng of camera-toting tourists in a wizened look of innocence, as if disapproving the vain Instagram and twitter paparazzos.

Waving straw fans, a kin-blooded group of elders appraise the ceremony with austere silence. The Osaka sun painting yellow splotches on their meditative frown lines. Bandana-headed boys pound the Taiko drums as the first group of flat-hatted girls bow deeply in a circle before Sumiyoshi shrine. Then with the syncopated rhythm of drums and woodblock strikes, they dip down into the earth with invisible plows, performing the first moves of the Sumiyoshi harvest festival dance.

It can be challenging to find active celebrants of cultural heritage in a country brimming with high-tech electro gadgets, cars, and robots – a tech junkie’s utopia. But as policemen wielding mini light sabers herd me into the siphoned viewing areas of one of Japan’s summer throwback festivals, my hopes of witnessing authentic local traditions are realized.

Donning a Spiderman hat from Osaka’s Universal Studios, I crop out the outstretched forearms of iPhones and cameras to capture photos of the anachronistic dance.

The warbling hum of seated monks on the backstage of Sumiyoshi shrine’s cypress wood floors leaves me oddly enchanted. The ceremony makes me think of old school teachers haranguing students on correct behavior; but the kids aren’t coaxed by singing lectures nor monkish divinity, they continue skipping and clapping as if never returning from playground recess.

The Shinto priests croon their incantations like a chorus of exotic birds, some of the monks whistling through bamboo flutes that give off the airy overtone of meditating in a peaceful temple garden. Wearing oversized green night gowns, thin ballooned pants, and black pouch hats, I imagine the monks are like divine parakeets, flying to the heavens in inflatable pajamas, and singing their prayers to Sumiyoshi Sanjin – one of the three deities of Shinto religion in Japan. In the dusty foreground of the shrine, the paddle-clapping girls chant and clap like playing a game of ring-around-the rosy tethered to an imaginary maypole, and keeping in perfect rhythm with the drummer boys.

No doubt the melodious effect of this quirky ensemble is blessing for a propitious harvest, one marked by youthful vitality and elderly wisdom.

Peace-fingering me in a yellow-flowered kimono, I meet Reiko as one of the dance performers, a high-school student from the Kansai area of Japan. “It’s fun to dance in summer with friends and family.” She says, fanning a plastic-Mickey Mouse fan over the runnels of sweat trickling down her powder-caked face.

Peace-fingering me in a yellow-flowered kimono, I meet Reiko as one of the dance performers, a high-school student from the Kansai area of Japan. “It’s fun to dance in summer with friends and family.” She says, fanning a plastic-Mickey Mouse fan over the runnels of sweat trickling down her powder-caked face.

We eat kakigori (shaved ice) in a teeming plaza of Vendors and tourists near Sumiyoshi shrine. Reiko goes on to tell me the folk legend of the harvest dance tradition, known as dengaku. Reputedly, empress Jungu, a Japanese empress from the early 3rd century AD, prepared for an invasion of Korea. The legendary queen, born from parents with mouthful-pronouncing names (Okinaganosukunenomiko and Kazurakinotakanukahime) dispatched young female rice planters to Sumiyoshi shrine to plant rice – thus to covet her war campaign as an auspicious event with divine favor. After receiving seeds from the main temple sanctuary, they walk to a sacred field. The seeds cultivated on this holy soil are given to farmers so that when the seeds sprout, the crops are harvested as magical grains of rice, believed to have power from Sumiyoshi Sanjin.

Warned by an oracle, the empress instructed the temple’s architect named Tamomi no Sukune, to enshrine the Shinto god before eventually immortalizing herself there.

Touted as one of the greatest summer festivals in Osaka city, Sumiyoshi festival is held over four days and congregates at the Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine or (Sumiyoshi Taisha). The Shinto temple garners an ancient reputation for being one of the oldest in Japan, only third to the Ise and Izumo shrines.

As a signature of its popularity, the temple brandishes a roofed hip-knob or okichigi, a samurai-crossed wooden centerpiece over five horizontal billets of timber. Without using a plethora of gaudy religious ornaments, the use of woodwork evokes a certain warrior attitude and simplistic charm – an aesthetic background for spiritual warriors like Empress jingu to meet and receive blessings for future battles.

Worshipped as the headquarters for 2,000 of Japan’s Sumiyoshi shrines, Sumiyoshi Taisha enshrines Sumiyoshi Sanjin as not only a god of harvest, but a protector of land, sea, and patron of waka, a Japanese style of poetry that implements 31 syllables in comparison to haiku’s truncated 17 syllable form. Holding her hand to hide her mirth, Reiko fails to suppress a schoolgirl giggle. “At some Sumiyoshi temples men bathe in the rice water.” According to folklore myth, a crane dropped the first seed, which sprouted as a rice-deity at Izu shrine. To honor this humble beginning, naked men climb down into the flooded farm field and jump and splash like skinny-dipping in a giant mud bath.

Ostensibly, the purpose isn’t just to create a full-monty like spectacle but to divine answers from a symbolic deity; a giant pole standing in the field, representing Sumiyoshi Sanjin, falls down at a certain side of the rice field (maybe due to the pool’s build-up of testosterone or from an all-together masculine pull) which answers fortune-telling questions for local villagers.

Ostensibly, the purpose isn’t just to create a full-monty like spectacle but to divine answers from a symbolic deity; a giant pole standing in the field, representing Sumiyoshi Sanjin, falls down at a certain side of the rice field (maybe due to the pool’s build-up of testosterone or from an all-together masculine pull) which answers fortune-telling questions for local villagers.

After a monk’s closing speech, the performers march back in procession through the city streets. “Walking through the Chinowa (a ring of straw) is good luck” says Reiko. “I want to do well on tests and go to a good university.”

She notes that the festival starts with a purification shower on Umi no hi (Sea Day July 3rd) and climaxes around the end of July known as Nagoshi Harai Shinji, where starry-eyed fortune-seekers not only duck their heads through for good luck, but to purify oneself of negative energies.

If You Go:

You can travel to the Otaue rice harvest festival on June 14th in Osaka. Please visit www.jnto.go.jp/eng/spot/festival/otauericeplanting.html

You can also attend the summer matsuri festival on Marine Day in Japan (July 16th or the third Monday of July) and from July 30th to August 1st.

The festival location is about 3 minute walk from Sumiyoshi Taisha Station on the Nankai Dentetsu line coming from Shin-Imamiya station. Or you can get off at Sumiyoshihigashi Station by taking the Nankai Koya line on the Nankai Electric Railway in Osaka city.

About the author:

Jason is an aspiring free-lance writer who has pitched his tent abroad in Czech Republic, Korea, and Japan, empowering youth and consulting foreign businesses and governments on English language skills and professional development. In his spare time, he finds time to write, energizing his synapses with quirky travel memoirs and budget-roughing misadventures, believing his endless vagabonding is on a fruitful quest for authenticity.

Image credits:

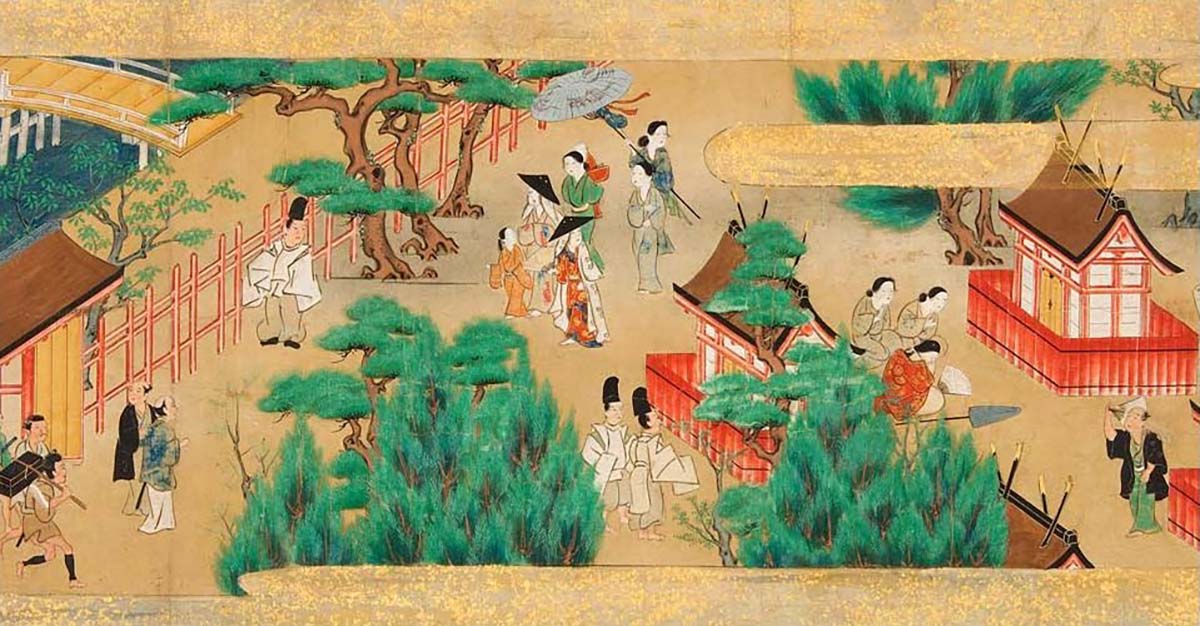

17th Century Festival at Sumiyoshi Shrine (detail), Japan, Edo period, 17th century, anonymous handscroll, ink, color and gold on paper, Honolulu Museum of Art by Unknown author / Public domain

All photos by Jason Templer, jasonw4770@yahoo.com