Before James Bond, There was The Man in Lincoln’s Nose

by Rick Neal

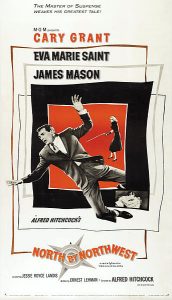

As any filmgoer can tell you, James Bond is easily the longest continuing character in movie history. Six different actors have played agent 007 in a film chronology that has spanned nearly half a century, but certain personality traits have remained constant: an insolent charm that borders on arrogance, a readiness to circumvent the rules that always leads to danger, and above all an astonishing success rate with members of the opposite sex. But before the dashing super agent bedded his first Russian spy or thwarted his first arch villian, there was Cary Grant scurrying across the face of Mount Rushmore and seducing Eva Marie Saint on board the 20th Century Limited train.

Mister Bond, meet your daddy.

Released in 1959 three years before the first Bond flick, Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest remains one of the most entertaining motion pictures of all time. It pops up repeatedly on lists of Greatest American Movies and thanks largely to Turner Classic Movies, is possibly the most televised of all Hitchcock films. Odd then, that one of his most famous pictures started as a vague notion about a guy hanging from Abraham Lincoln’s nose.

Released in 1959 three years before the first Bond flick, Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest remains one of the most entertaining motion pictures of all time. It pops up repeatedly on lists of Greatest American Movies and thanks largely to Turner Classic Movies, is possibly the most televised of all Hitchcock films. Odd then, that one of his most famous pictures started as a vague notion about a guy hanging from Abraham Lincoln’s nose.

By 1950 Hitchcock was already an accomplished filmmaker, having directed such classics as The 39 Steps, Shadow of a Doubt, and Notorious. But film historians and fans generally agree that The Master of Suspense reached his apex in the 1950s. Strangers On a Train, Rear Window and Vertigo are among his finest and most widely analyzed works, exploring dark themes of mistaken identity, voyeurism, and obsession. So after the release of the complex psychological thriller Vertigo in 1958, Hitchcock wanted his final motion picture of the decade to be an enjoyable romp free of the symbolism prevalent throughout that decade’s previous releases.

After a successful lunchtime meeting at the Polo Lounge, Hitchcock hired Ernest Lehman as the scriptwriter for the new MGM picture. The duo brainstormed several suggestions for a script, but none seemed viable until Hitchcock mentioned an idea he’d had seven years earlier that started with an image of a man hanging from Abraham Lincoln’s nostril on Mount Rushmore. That idea grew into a vague narrative about a CIA decoy who becomes involved in international espionage and mistaken identity. Lehman was inspired by the concept, eventually transforming it into an amusing and engaging script that he intended as “the Hitchcock picture to end all Hitchcock pictures.”

The plot is convoluted to say the least, and yet it succeeds. Roger O. Thornhill, a dashing New York advertising executive, is kidnapped by a group of spies after he is mistaken for a CIA agent. Thornhill narrowly escapes, but is soon falsely accused of an assassination at the United Nations. Suddenly, the spies and the police are both after him. In order to prove his innocence, he boards the 20th Century Limited train to Chicago in search of the real agent. Onboard he meets and seduces beautiful Eve Kendall (or is it the other way around?) who sends him to that infamous encounter with a deadly crop dusting plane. After a few more plot twists Thornhill is whisked off to South Dakota, setting up the memorable climax on Mount Rushmore.

Jimmy Stewart, who had starred in Vertigo, lobbied hard for the role of Thornhill, but Hitchcock blamed Vertigo’s poor box office on Stewart, who the director thought looked too old. The studio suggested Gregory Peck or William Holden, but Hitchcock insisted on Cary Grant, who ironically was four years older than Stewart. At first Grant refused the role, believing that at fifty-five he was getting too old to play debonair romantic leads, but then Hitchcock offered the astounding sum of $450,000, plus a share of the profits. When a further nine weeks of shooting were required he also received an extra $300,000 in overtime pay.

Jimmy Stewart, who had starred in Vertigo, lobbied hard for the role of Thornhill, but Hitchcock blamed Vertigo’s poor box office on Stewart, who the director thought looked too old. The studio suggested Gregory Peck or William Holden, but Hitchcock insisted on Cary Grant, who ironically was four years older than Stewart. At first Grant refused the role, believing that at fifty-five he was getting too old to play debonair romantic leads, but then Hitchcock offered the astounding sum of $450,000, plus a share of the profits. When a further nine weeks of shooting were required he also received an extra $300,000 in overtime pay.

Almost from the moment he signed on the legendary star bellyached that he wanted out. He argued that the plot made no sense (a not totally unfounded criticism) and that Lehman’s script lacked humour. Whatever his misgivings, he gave a funny and restrained performance in what has become one of his signature roles, looking composed even while running from a crop duster. For the female lead, MGM wanted Cyd Charisse while Cary Grant fancied Sophia Loren. Hitchcock, who had a penchant for blondes, raised some eyebrows when he cast Eva Marie Saint. Her previous roles were dowdy, girl next-door types but Hitchcock saw something in her that convinced him she would be effective as the alluring spy. His hunch paid off. The romantic scenes between the two stars sizzle in spite of their twenty-year age gap and are, for the fifties, surprisingly risqué. Hitchcock leaves little doubt how they passed the night on that train. The censors also missed the Freudian symbolism of the final scene, when Thornhill pulls Kendall on to the bed as their shiny train slips into a dark tunnel.

As unforgettable as the two leads were, the movie would not be the masterwork it is without its marvelous supporting cast. James Mason oozes velvety charm as the leader of the spy ring. Watching him trade verbal barbs with Grant is pure wicked pleasure. Martin Landau is equally sinister as Mason’s somewhat effeminate sidekick, while Jesse Royce Landis provides comic relief as Grant’s wisecracking mother, even though she was only seven years his senior.

North by Northwest was made between August and December 1958, with a few re-takes in April 1959. Hitchcock couldn’t get permission to shoot inside the United Nations, so he had it filmed with a hidden camera and then recreated the interior on a soundstage. The scene of Grant entering the building was also shot with a concealed camera.

Authorities wouldn’t allow Hitchcock to film an attempted murder on the real Mount Rushmore, so the scene was shot in the studio on a detailed replica. Everything was staged with great care to avoid showing disrespect to the faces on the monument. Hitchcock actually did want to include a sequence where Thornhill would hide inside Lincoln’s nose and be discovered after a sneezing fit. After a lengthy argument, someone convinced the obstinate director that the scene was undignified and the idea was scrapped.

Authorities wouldn’t allow Hitchcock to film an attempted murder on the real Mount Rushmore, so the scene was shot in the studio on a detailed replica. Everything was staged with great care to avoid showing disrespect to the faces on the monument. Hitchcock actually did want to include a sequence where Thornhill would hide inside Lincoln’s nose and be discovered after a sneezing fit. After a lengthy argument, someone convinced the obstinate director that the scene was undignified and the idea was scrapped.

The crop duster scene is one of the most widely revered in film history. The action takes place on a highway by an open field, where Thornhill has been sent to meet a CIA agent. The only other person around is a man waiting for a bus, who remarks that a plane in the distance is “dustin’ crops where there ain’t no crops.” Suddenly, the crop duster swoops down on Thornhill and begins shooting. He runs into a nearby cornfield but the plane sprays him with pesticide. In desperation, he runs onto the highway in front of an approaching gasoline tanker truck, which stops just as the oncoming plane crashes into it and explodes in a ball of fire.

Filmed in broad daylight and without music, Hitchcock employed a series of “rapid fire” camera shots to craft an incredibly thrilling scene that has been held up as a prototype for generating suspense. It is difficult to say anything original about it, except to point out that it is almost completely unnecessary. You may rightly ask why Hitchcock didn’t have the bad guys just drive up to Thornhill and shoot him. Perhaps the answer is that he didn’t want to deprive cinema of one of its most lionized sequences. And maybe that’s reason enough.

In spite of Hitchcock’s desire that North by Northwest be devoid of the symbolism found in his earlier efforts, it has been widely scrutinized for its themes of deception, mistaken identity, and Cold War morality. Everyone is playing a role and no one is who they seem to be. However, Hitchcock and Lehman scorned claims of symbolism, claiming that the film is best enjoyed as the capricious tour de force they intended it to be.

Critics have pointed out that much of the plot was re-worked from earlier Hitchcock efforts, deriding the motion picture as nothing but a glorified “greatest hits” package. There is some strength to this argument. This was the last of several movies he made that exploit the “wrong man” theme, beginning with The 39 Steps (1935), while the climactic scene on Mount Rushmore borrowed heavily from the ending of Saboteur (1942), set on top of the Statue of Liberty. But it’s a testament to Hitchcock’s genius that he was able to take these various elements and whip them into a delicious, if slightly off-balance concoction that invites repeated viewings.

Ian Fleming stated that James Bond was based in some measure on the ultra suave Cary Grant. In fact, the actor was asked to play 007 in the first Bond flick, Dr. No (1962). Cary, who was pushing sixty, understandably turned down the offer, but in retrospect it seems fitting that he should have played the iconic character in his inaugural screen appearance. A young Scottish actor by the name of Sean Connery was finally cast partially because of his resemblance to Grant. Aside from the rakish leading man, other similarities between North by Northwest and the James Bond films have been noted, such as the exotic settings and the espionage. But the truth is, the spirit of this film inhabits nearly every action picture produced in the last fifty years. When movies like The Fugitive (1993) and The Usual Suspects (1995) are described as classic thrillers, North by Northwest is the original classic thriller from which they trace their ancestry.

Mount Rushmore and Black Hills Safari Tour from Rapid City

Movie Information:

About the author:

Rick Neal is a free lance writer living in Vancouver, Canada. He’s been published in www.offbeattravel.com, www.hackwriters.com, and in Senior Living magazine. Rick has been to Europe, Turkey, Mexico, Central America, China, and Vietnam. Rick hopes to make South America his next destination.

Photo credits:

North by Northwest Cary Grant still from movie trailer in Public Domain via Wikimedia

Movie poster: Copyrighted by Loew’s, Incorporated. Incorporates artwork by Saul Bass / Public domain

James Mason, Eva Marie Saint and Cary Grant at Mount Rushmore: Motion Picture Daily name at top of page / Public domain

North by Northwest Eva Marie Saint still from movie trailer in Public Domain via Wikimedia