by Lynne Howden

Peruvians, dressed in parkas, hammered on the driver’s enclosed compartment, yelling “Frio, frio!” The only heater on the bus appeared to be under my seat. I kept this good fortune to myself, moving my feet closer to the warmth. “Better to hold on than use the toilet,” my husband said. The Cusco travel agent had booked us on a tortuous overnight bus ride to Puno; destination Lake Titicaca.

Arrival time 5:15 a.m. We waited an hour in the dark and cold before the travel agent’s office opened. Joseph told us to leave all but the bare essentials behind; there was not much room in the boat. What’s essential? Rain ponchos would not be needed, he assured us. As we made a run for the launch, the skies opened, drenching us with ice pellets. Cursing the agent, I shivered in the downpour for the half-hour ride to the Uros Islands, five kilometers off shore. Layering up with all the clothing I brought did no good; there was no shelter from the rain. Would I ever feel warm again?

Lake Titicaca is located on the border of Peru and Bolivia, 3810 meters above sea level. The native Uros are indigenous people pre-dating the Incas. As of 2011, about 1200 Uros lived on about 60 reed islands, where the shelters are also made of reeds.

Rows of colorfully costumed natives lined up on the shore, welcoming us to their floating reed island. Smiling shyly, revealing gaps in their teeth, the mamas invited us into their huts. Once in the dimly-lit shelters, they opened their bags of goodies, enticing us to buy with entreating looks and gestures. The bright clothes and proud demeanor belie a sparse existence; the inhabitants of the islands are hunters and gatherers and use tourism to supplement their income. Who could refuse to buy a carved gourd or woven mat?

Rows of colorfully costumed natives lined up on the shore, welcoming us to their floating reed island. Smiling shyly, revealing gaps in their teeth, the mamas invited us into their huts. Once in the dimly-lit shelters, they opened their bags of goodies, enticing us to buy with entreating looks and gestures. The bright clothes and proud demeanor belie a sparse existence; the inhabitants of the islands are hunters and gatherers and use tourism to supplement their income. Who could refuse to buy a carved gourd or woven mat?

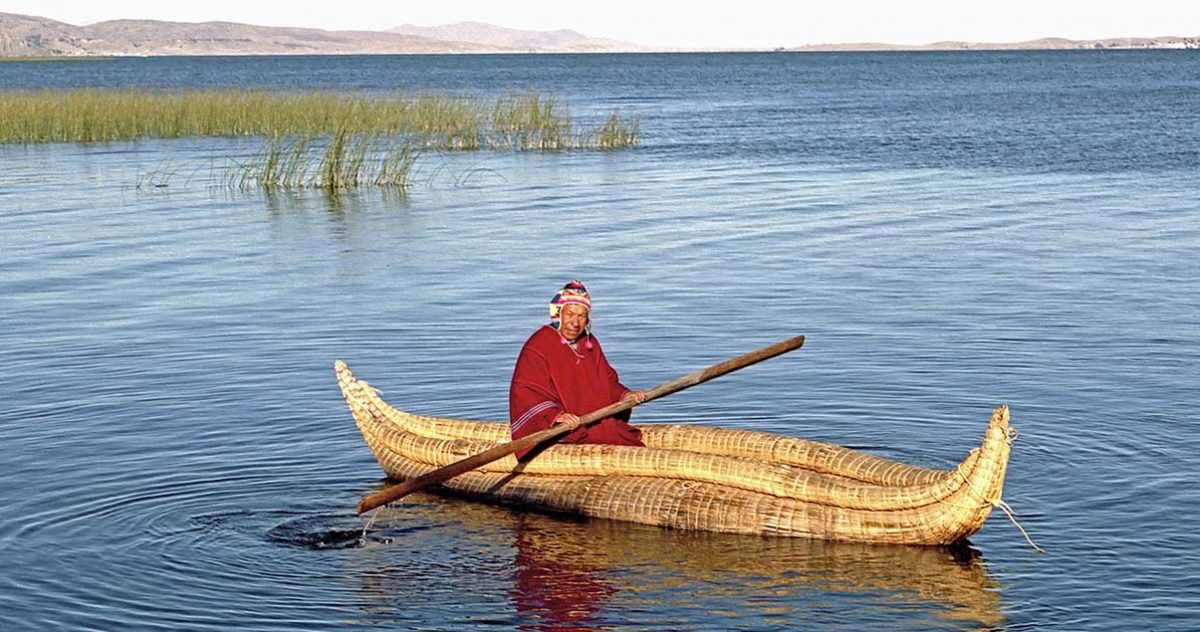

Proudly, the papas demonstrated how they built the “Viking-style” boats, tying reeds together with ropes. The boats can be up to 30 meters long and are also used for fishing and hunting seabirds. Twenty of us piled into the totora boat for a short ride; the captain and his son serenading us as we drifted to another island where we bought a sandwich and coffee, our first food of the day. Suddenly, the sun erupted from behind the clouds, enveloping us in its heat. It was time to move on to two other islands with the local guide.

Proudly, the papas demonstrated how they built the “Viking-style” boats, tying reeds together with ropes. The boats can be up to 30 meters long and are also used for fishing and hunting seabirds. Twenty of us piled into the totora boat for a short ride; the captain and his son serenading us as we drifted to another island where we bought a sandwich and coffee, our first food of the day. Suddenly, the sun erupted from behind the clouds, enveloping us in its heat. It was time to move on to two other islands with the local guide.

On Amantaní we were welcomed at the dock by an array of brightly-costumed “mamas,” waiting to lead us up the steep terraced hillside to our hosts’ homes for the night. There are 800 families, about 4000 people, living on this rugged island. The ten communities take turns hosting tourists. Our hostesses were gaily arrayed in hot pink puffy skirts, green, blue and pink floral motif inlaid on white cotton peasant blouses, cinched tightly at the waist by a chumpi belt. Around their shoulders, they wore a chuco, a black shawl that doubles as a head covering.

On Amantaní we were welcomed at the dock by an array of brightly-costumed “mamas,” waiting to lead us up the steep terraced hillside to our hosts’ homes for the night. There are 800 families, about 4000 people, living on this rugged island. The ten communities take turns hosting tourists. Our hostesses were gaily arrayed in hot pink puffy skirts, green, blue and pink floral motif inlaid on white cotton peasant blouses, cinched tightly at the waist by a chumpi belt. Around their shoulders, they wore a chuco, a black shawl that doubles as a head covering.

After introductions, the mamas shyly led us up the steep, rocky paths to their simple adobe-bricked homes. Our mama was Jenni (Yenni), a 26-year-old, who had trained as a teacher but couldn’t deal with the rambunctious boys! The arduous climb was a challenge to those suffering from altitude sickness. I was happy to have spent a few days before acclimatizing to the altitude in Cusco. Once we arrived at our home for the night, Jenni served us a fragrant, refreshing tea made from muna, a type of mint, that she picked on the way up, that helps alleviate altitude sickness. Her command of English was surprisingly good; her parents did not speak English or Spanish.

In the courtyard, Jenni’s father, 76, crushed dried wheat stalks with his feet while her mother, Valentina, ground them with a mortar stone. The locals also grow maize, quinoa, potatoes and barley, trading them for other goods on the mainland. Host families are paid about US$20 per person for the homestay. We were shown to our private bedroom, lit by candlelight and equipped with plenty of blankets for the cold night ahead, then treated to a basic meal of quinoa soup, boiled potatoes, rice and fried cheese. The islanders eat very little meat, as it’s so expensive. The food was delicious and freshly prepared, and the aromas enticed us to eat several bowls of the soup. I was not looking forward to visiting the shared outhouse with its primitive water-bucket flushing toilet 100 meters away in the middle of the night, so resolved to limit my liquid intake in the evening.

In the courtyard, Jenni’s father, 76, crushed dried wheat stalks with his feet while her mother, Valentina, ground them with a mortar stone. The locals also grow maize, quinoa, potatoes and barley, trading them for other goods on the mainland. Host families are paid about US$20 per person for the homestay. We were shown to our private bedroom, lit by candlelight and equipped with plenty of blankets for the cold night ahead, then treated to a basic meal of quinoa soup, boiled potatoes, rice and fried cheese. The islanders eat very little meat, as it’s so expensive. The food was delicious and freshly prepared, and the aromas enticed us to eat several bowls of the soup. I was not looking forward to visiting the shared outhouse with its primitive water-bucket flushing toilet 100 meters away in the middle of the night, so resolved to limit my liquid intake in the evening.

After a dinner of barley soup (we declined potatoes and rice), Jenny dressed us in the local costumes for the dance at the community hall. Men wear ponchos and traditional knitted alpaca toques with earflaps. We laughed at each other wearing these costumes over our long pants and hiking boots; but it was all part of the unique cultural experience. Under the full moon, armed with flashlights, we made our way to the hall to take part in dancing while a local band created lively music with drums, flutes and guitars. I can’t say I enjoyed dancing, though, as it’s hard enough to breathe at 4000 meters while being tightly bound, never mind dancing!

Both Amantani and Taquile, where we went the next day, have no electricity or running water as oil for generators became too expensive to transport from the mainland years ago. A few families have solar power; otherwise, it’s candles for light and wood for cooking. On Taquile, the big craft is knitting, which is done by men and boys, who learn to knit the chullo, a hat which indicates marital or public status.

Both Amantani and Taquile, where we went the next day, have no electricity or running water as oil for generators became too expensive to transport from the mainland years ago. A few families have solar power; otherwise, it’s candles for light and wood for cooking. On Taquile, the big craft is knitting, which is done by men and boys, who learn to knit the chullo, a hat which indicates marital or public status.

Women weave the sturdy belts, centuros, that hold up to 50 kgs. and the chuspa (coca leaf bags) carried by men who ceremonially exchange a few leaves on meeting. Seventy per cent of the islanders are Catholic while the remainder are Seventh Day Adventists. Everything must be hauled up the 540 steps from the harbor; you see people of all ages carrying heavy loads on their backs in the colorful woven blankets. We had nothing but admiration for these resilient islanders. A simple life is certainly not an easy life.

We would carry the serenity and warmth of a brief encounter with the people of Titicaca with us, as we moved on from the lake at the top of the world.

If You Go:

If time permits, it’s worthwhile booking a two-day tour which stops at the Uros Islands before visiting the larger natural islands of Amanataní and Taquile. These two islands are inhabited by the indigenous Aymara people who have their own unique customs and traditions, not to mention there are numerous ancient sites and breathtaking vistas.

We spent a night in Puno so we could travel back to Cusco during the day, through the stark but interesting altiplano, rolling grasslands with their grazing herds of llamas and alpacas, at 4-5,000 meters elevation. Near villages, locals bathed or washed clothes in the river, spreading them out to dry in the sun.

Getting there: Air from Lima (1:40 hrs) or Cusco (1:00 hr) to Juliaca, which is 44 km. (1 hour) by road from Puno. Airlines are Avianca and LATAM.

Train – Peru Rail runs a luxury train between Cusco and Puno six days a week (except Tuesdays) for US$404 return, including lunch, tea and entertainment.

Bus – Several reputable companies, such as Cruz del Sur and Turismo Mer, make the 7:30 hour-trip from US$17 each way.

Full Day Tour: Uros and Taquile Islands on the Titicaca Lake from Puno

References:

10 Things You Should Know Before Visiting the Uros Floating Islands

Kayaking on Lake Titicaca to Uros and Taquile Floating Islands

About the author:

Lynne Howden is a retired ESL teacher who has been interested in history, writing, travel, photography and learning about other cultures for most of her life. She and her husband live in Vancouver and have travelled to all continents, except Antarctica. You can follow her travel blog, with photos at https://travellingfools.blogspot.com and her photos on Flickr at https://www.flickr.com/photos/26058675@N02/albums

10-Day Tour from Lima: Machu Picchu, Lake Titicaca and Colca Canyon

Top photo by Dennis Jarvis from Halifax, Canada / CC BY-SA

Photos #2 – #6 © by Lynne Howden