Alberta, Canada

by Elizabeth Templeman

The Navajo were “careful to obliterate every trace of their temporary occupation…. Just as it was the white man’s way to assert himself in any landscape, to change it, make it over a little (at least to leave some mark of memorial of his sojourn), it was the Indian’s way to pass through a country without disturbing anything, to pass and leave no trace, like fish through the water… to vanish into the landscape, not to stand out against it.”

– Willa Cather, Death of an Archbishop

Art reflects the social, historical, political and economic contexts of the time during which it was produced, according Charles Olton, an art theorist and teacher. Any work of art, he explains, will either celebrate or rebel against those contexts. This can be said of painting and sculpture, but, holds equally true of dance or theatre—or even essay writing.

In understanding art, the second factor to consider, according to Olton, is the particular artistic tradition from which the work of art springs: its contemporary influences, in other words. As with its socio-cultural contexts, the individual work of art will either conform to the artistic context, or defy its constraints.

“The Writing-On-Stone Provincial Park” situates as the earth splits, cracking the dusty plains open to reveal layers of ancient geography—sandstone scrubbed by rain and wind and glacier and who knows what violent or persistent acts of nature. Bumping against the southerly border of Alberta, north of the American Badlands, it lies east of the Cypress Hills and along the warm and chalky Milk River.

“The Writing-On-Stone Provincial Park” situates as the earth splits, cracking the dusty plains open to reveal layers of ancient geography—sandstone scrubbed by rain and wind and glacier and who knows what violent or persistent acts of nature. Bumping against the southerly border of Alberta, north of the American Badlands, it lies east of the Cypress Hills and along the warm and chalky Milk River.

In the area of the park, temperatures soar as high as forty-one and can plunge to forty-three below. The land has assumed those similarly dizzying pitches, from ridge to river. This land is no gradually unfurling surface. Here, the earth has heaved and fractured, shuddered and convulsed, exposing Hoodoos and middens and coulees, and expanses of wild grasslands.

he parkland is known as Aisinaihpi — “Where the Drawings Are” — in the language of the Blackfoot. My family visited Writing-On-Stone in June of 2001. On our second morning at the park, we followed other tourists into the bus that would deposit us within the portions of the park which have been closed off to tourists for the past decade.

he parkland is known as Aisinaihpi — “Where the Drawings Are” — in the language of the Blackfoot. My family visited Writing-On-Stone in June of 2001. On our second morning at the park, we followed other tourists into the bus that would deposit us within the portions of the park which have been closed off to tourists for the past decade.

Our guide for the morning was an earnest and knowledgeable young woman, a sturdy individual with the ruddy complexion of one who spends most of her life out of doors. Our group formed, on the whole, an engaged, mildly curious, amenable, and passive audience. We provided the perfect antidote for her enthusiasm. Something about the bright sunshine, or the warmth, or perhaps just the novelty of bumping along on a bus like school kids, didn’t bring out the best in us.

My kids and I found ourselves mesmerized by the names and dates scratched out on those rock faces rising all around us as we tumbled off our bus. “Edward Robinson was here, 1912” tugged at our attention. While the legends represented in faint rust-coloured outlines were exotic and alien to us, we recognized the impulse to assert our individuality across time, by inscribing a surface with a name. Our guide remained resolutely unimpressed when our boys pointed out, with growing excitement, dates stretching back to 1887, from the years when the area was an outpost for the NW Mounted Police.

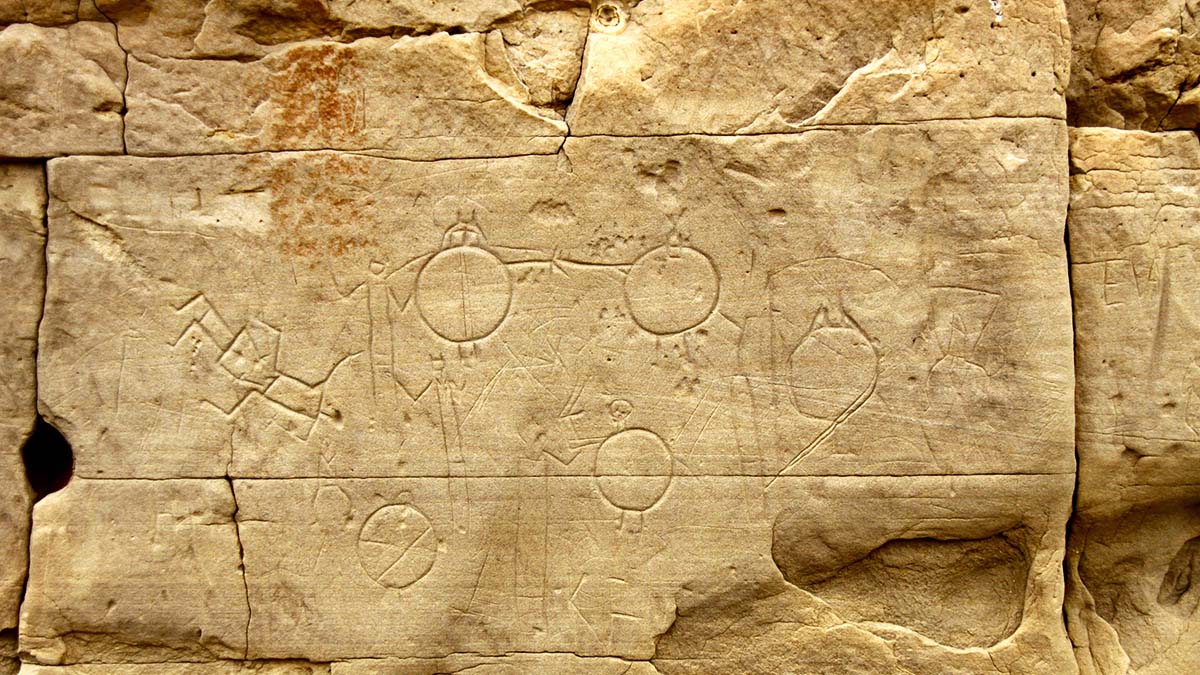

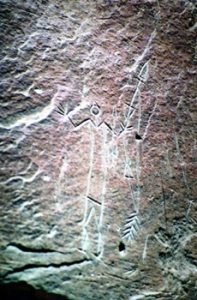

She explained, with patient determination, how a proclamation that you had been here on such and such a date pales in comparison to the powerful narrative unfolding in the faded etching of rock on rock, depicting horses and tepees and human forms, holding what could be tools, or spears, or arrows. These form the works of whole communities, etched out for reasons largely unknown to us today. They represent social and cultural mysteries, and are centuries old—thought to extend as far as five thousand years, according to the Government of Alberta.

And yes, to us the petroglyphs are mysterious, and even eloquent, in a mute and remote way. But they leave me baffled, excluded, distant. Which is fitting, and parallels the impression the land forms make upon me.

Not that layers of significance and intentionally spill forth from the letters which spell out a man’s name and the date he stood at this same rock face. I’m still left to infer the terrible loneliness and power of this land in 1912, or in 1887. I still have to wonder to whom this named individual expected to be announcing his existence. There is so much left to our imaginations.

Not that layers of significance and intentionally spill forth from the letters which spell out a man’s name and the date he stood at this same rock face. I’m still left to infer the terrible loneliness and power of this land in 1912, or in 1887. I still have to wonder to whom this named individual expected to be announcing his existence. There is so much left to our imaginations.

What is definite is that I can’t dismiss it. The graffiti is compelling. I can’t share the disdain of the park ranger leading us along through these parched hills in the broiling late morning sun. I’m not convinced that these writers knowingly defiled ancient art. Who can be sure they weren’t adding their own message to layers of message beneath? Who can say they would have recognized the other as art? Who can know whether they rebelled by defacing—or conformed by contributing to—the larger text represented by human markings upon the landscape?

Consider the utter desolation facing the young man who may have found himself stationed at this police outpost in the 1880s. Would he be among friends, or with a brother, or a lone recruit new to the force? Perhaps it was in search of adventure, or to fulfill some notion of duty and honour, that he found himself on a peacekeeping mission in such an peculiar surrounding. Maybe, like us, he had not even dreamed of the geological oddity of a hoodoo, mushrooming from the ground in a swell of fragility and preposterous dimensions. Maybe the winds rustling the grasses and whirling grit drove him near to despair.

What of the young Blackfoot who scratched out an image from his vision quest, after solitary days of hunger and scorching sun? How can I begin to comprehend such a trial? What would it possibly have meant to him, that I bear witness to the trace of his quest? It’s all beyond my ken.

And hovering over both the drawings of the Blackfoot and the graffiti of the cowboy or adventurer, juts a ledge on which one can—craning one’s head just so—make out the profile of a man. Blink and refocus, and it becomes the outline of a badger, and then an eagle. Surely the forces of nature are mocking our very human preoccupation with finding likenesses. Up there, the creator is as enigmatic as the creation, and wholly without ego.

Surely both of those humans felt dwarfed by this landscape, diminished by the bony harshness of the place, a common denominator which links us all. Both felt some compulsion, or some elemental need, to proclaim their humanity. One way, by tracing name and date, might have seemed, to its creator, as an imagined facsimile of the self. In the Euro-western way, the statement would read: “It is me. I am here. This is my name, and this, my time.”

Surely both of those humans felt dwarfed by this landscape, diminished by the bony harshness of the place, a common denominator which links us all. Both felt some compulsion, or some elemental need, to proclaim their humanity. One way, by tracing name and date, might have seemed, to its creator, as an imagined facsimile of the self. In the Euro-western way, the statement would read: “It is me. I am here. This is my name, and this, my time.”

The other says, perhaps, something less individual, more timeless, about a communal impression of interaction with the world, to some god or other humankind. The message could have been, “This was an extraordinary horse.” Or “Many worthy men died in this battle.” But just possibly some of these messages might have been mundane, or even frivolous. One such pictograph—fainted outlined in ochre and which we all gawk at and snap pictures—may have meant “Smokey John is a rube,” or “I love Dawn Willow-thrush.” How can we know?

Information provided by the Government of Alberta tells us that the Blackfoot had forced other inhabitants away from this land. It had been home to Shoshoni, Sioux, Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, before the Blackfoot Confederation settled there. It is thought that some of the rock art dates back to the earlier peoples. The pictographs, those symbols painted onto the stone with ochre or charcoal, appear more transitory, yet may be more recent. Who would ever outline an image on rock with crushed iron mixed in animal fat and expect it to outlast the lifespan of generations, to persist through flood and drought and battles and plagues?

The petroglyphs, those etched into the surface, were first carved with stone or bone or antler, and much later with metal implements. Those might have been created with the intent to assert ones presence, to change the landscape, even to obliterate the spirit or symbols of a previous dweller.

Art could be no more than the human voice ringing out in the wilderness. It may ring in protest, breaking free of the chorus of voices, or in glorious harmony. Maybe all such voices really say, at their barest essence, is “I was here. We were here. Take note.” It could all be no more than this, and yet, maybe the spirit of humanity hinges upon it.

Canadian Badlands Day Trip from Calgary

If You Go:

Weblinks for travel to Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park

Writing-on-Stone on Wikipedia

Travel Alberta: Writing-On-Stone park

About the author:

Elizabeth Templeman lives at Heffley Lake, BC and teaches at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, BC. In 2003, Oolichan Books published a collection of creative non-fiction pieces called Notes from the Interior. Her essays have appeared in various magazines and journals including High Plains Literary Review, Harpweaver, Mothering, The River Review/Revue Rivere, Canadian Women’s Studies, and Wordworks. She’s reviewed non-fiction for Fourth Genre, and Canadian fiction for Southern Humanities Review.

Photo credits:

First petroglyphs detail photo by: Matthias Süßen / CC BY-SA

All other photos are by Nicole Templeman.