by Paris Franz

At first glance, the town of Bletchley, some fifty miles to the north of London, appears to be an unremarkable kind of place. For a long time, as far as the outside world was concerned at least, the town’s main claims to fame were the busy railway junction and the manufacture of bricks.

At first glance, the town of Bletchley, some fifty miles to the north of London, appears to be an unremarkable kind of place. For a long time, as far as the outside world was concerned at least, the town’s main claims to fame were the busy railway junction and the manufacture of bricks.

As for the manor house at Bletchley Park, just across the railway tracks from the town centre, it has been known to make architectural historians shudder. Its idiosyncratic jumble of building styles – the Italianate pillars, mock Gothic arches and rococo ceilings – can most charitably be explained as an architectural experiment on the part of the Victorian nouveau riches.

Yet it was the unremarkable nature of the place that turned out to be the key to its greatness. For it was here, far from the bombs pounding London and the attention of enemy spies, that hundreds of formidably brainy people broke German, Italian and Japanese codes during World War Two.

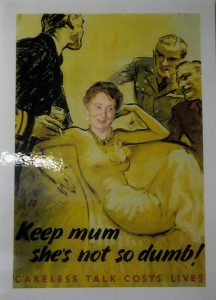

Careless Talk Costs Lives

Such was the strength of the veil of secrecy surrounding Bletchley Park that it didn’t begin to lift until the 1970s. Even those who worked here were forbidden to talk to each other about what they did. Careless talk could cost lives, and there are many posters on display around the park warning of the perils of indiscretion.

Such was the strength of the veil of secrecy surrounding Bletchley Park that it didn’t begin to lift until the 1970s. Even those who worked here were forbidden to talk to each other about what they did. Careless talk could cost lives, and there are many posters on display around the park warning of the perils of indiscretion.

On descending from the train at Bletchley station on a bright sunny day, I thought of what it must have been like for the new arrivals, many of whom had never left home before. If they arrived at night, they would have needed a guide, for all that the park was just across the way, as the blackout plunged everything into darkness.

For the mathematicians and classicists, linguists, administrators and messengers who were posted here, it was an introduction to an intense and demanding world.

My arrival was a little less fraught. It was a short walk from the station to the fifty-five acres of Bletchley Park, although once there, it was a little difficult to know where to start. There are a range of films and interactive displays in the entrance block, Block C, where you buy your ticket, along with a fascinating exhibition on modern cyber security. There’s also a cafe and a bookshop, and I knew I would have to be disciplined, or I would likely get distracted and never see the rest of the site.

I eventually opted to walk across the park to the ornamental lake and the manor house beyond and then make my way back. The lake was pretty and peaceful in the autumn sunshine, with a breeze rustling the leaves and rippling the water. It was easy to imagine code-breakers taking a well-earned rest by the water’s edge.

I eventually opted to walk across the park to the ornamental lake and the manor house beyond and then make my way back. The lake was pretty and peaceful in the autumn sunshine, with a breeze rustling the leaves and rippling the water. It was easy to imagine code-breakers taking a well-earned rest by the water’s edge.

Breaking Codes and Social Barriers at Bletchley Park

The lake used to freeze over in winter, allowing for skating. It was also the scene for one of Bletchley Park’s most famous anecdotes, concerning the mathematician Josh Cooper. He was walking by the lake one day, so the story goes, coffee cup in hand and deep in thought. He then threw up his hands, tossed his coffee cup in the lake, and shouted, “I’ve done it!” before racing back to one of the huts to crack another code.

Eccentric boffins are an integral part of Bletchley Park lore. The place seemed to deliberately foster an informal, slightly anarchic atmosphere, with little emphasis on rank, all the better to encourage lateral thinking. The Enigma machine was not going to be broken by going by the book.

As for the mansion, its style can only be described as eclectic. Sir Herbert Leon and his wife Fanny bought the house in 1883, and almost immediately embarked on an extravagant building programme, embracing a wide range of architectural fashions.

Inside, it is all warm wood panelling, stained glass windows, narrow passageways and chandeliers. Some of the new recruits, used to rather grander places, regarded it as a Victorian monstrosity, while for others it represented the kind of stately home they never thought they would enter. Aside from its code-breaking role, the Bletchley Park operation is emblematic of the social upheaval of the period.

Inside, it is all warm wood panelling, stained glass windows, narrow passageways and chandeliers. Some of the new recruits, used to rather grander places, regarded it as a Victorian monstrosity, while for others it represented the kind of stately home they never thought they would enter. Aside from its code-breaking role, the Bletchley Park operation is emblematic of the social upheaval of the period.

The Government Code and Cypher School moved into Bletchley in 1938, as rumours of war gathered pace. The operation rapidly became too big for the main house, and a series of rather ramshackle huts and, later, somewhat sturdier blocks were built to accommodate the code-breakers and linguists.

The huts were spartan, utilitarian spaces, manned around the clock in eight-hour shifts. The evocative reconstructions, complete with soundtracks and images projected onto the walls, give a strong impression of what it must have been like. Inside, dimly lit rooms radiate off long, central passageways. Heavy blackout curtains are drawn over the windows, and piles of decoded messages, waiting to be translated, lie atop scuffed wooden desks.

Hut 8, which focused on breaking the Naval Enigma code, key to winning the Battle of the Atlantic, is a little brighter. The hut boasts a number of interactive displays, where you can test your own skills at seeing patterns and breaking codes. You can also visit Alan Turing’s office, where you can sit in his chair and attempt to look smart.

Challenges and Deceptions in Block B

Block B houses the main museum on the site, complete with multiple Enigma machines, the largest such collection in the world. Each branch of the German military had their own version, modified in various ways to increase security. The settings were changed daily, and the addition of extra rotors and a plug board made cracking the Enigma machine a much more difficult proposition. Just thinking about it gave me a headache.

Block B houses the main museum on the site, complete with multiple Enigma machines, the largest such collection in the world. Each branch of the German military had their own version, modified in various ways to increase security. The settings were changed daily, and the addition of extra rotors and a plug board made cracking the Enigma machine a much more difficult proposition. Just thinking about it gave me a headache.

The other exhibits include motorbikes used by the despatch riders who carried messages from listening posts around the country to Bletchley Park, posters, multimedia displays and the story of the cracking of the Lorenz cypher. I particularly enjoyed the tales of the double agents such as Garbo, and I couldn’t help but wonder at their nerve. Some people like to live dangerously.

The exhibition also houses a display on the work of Alan Turing, as well as a reconstruction of a Bombe machine, a large, noisy and vital construction that decoded messages on an industrial scale. Women of the Women’s Royal Naval Service, the Wrens, tended the machines day and night.

The sun was sinking as I made my way out of Bletchley Park and headed back to the station for the train to London. The visit had given me a lot of food for thought, and made me regret, briefly, that I hadn’t paid more attention in maths class.

If You Go:

♦ Bletchley Park is easy to get to. The Park is a short walk from Bletchley train station, which is easily accessible from London Euston, Coventry and Birmingham New Street. The Park is a National Rail 2For1 Attraction, which means two people can visit for the price of one, provided they both have national rail tickets and a 2For1 voucher. You can find out more information about the scheme and download a voucher at www.daysoutguide.co.uk/bletchley-park

♦ For information on the latest news and events from Bletchley Park, you can check their comprehensive website at www.bletchleypark.org.uk

Historical London Walking Tour including Westminster and Entry to Churchill War Rooms

About the author:

Paris Franz is a London-based freelance writer. She has had work published in a variety of web and print publications, including The Independent, Wanderlust, Decoded Past and Europe Up Close. See more of her work at www.parisfranz.com

All photos by Paris Franz:

Bletchley Park manor house

Poster advertising Bletchley Park

Keep Mum, She’s Not So Dumb

The lake at Bletchley Park

Hut interior

Enigma machine

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.