by Georges Fery

Pizarro’s arrival was the most significant event since the city’s foundation. Everybody gathered at the port to see the gold and silver, the colorful fabrics, the ceramics, and the horse-like animals (llamas). The crew members who had returned with Tafur bitterly deplored their lack of resolve. The name Perú, instead of Birú, was officially recognized and spread from mouth to mouth and from streets to taverns. The “Eastern Enterprise” was renamed the “Perú Enterprise.” Not so happy was Governor Pedro de los Rìos, for he was concerned that should many people leave for the new land, it would depopulate the government of Tierra Firme.

The partners realized they needed their discovery to be recognized by the Crown in Madrid. After arguing about the terms of a potential contract, they agreed that Pizarro should go to Spain, where he would ask for titles for each of them: governor of Perú, for Pizarro; “adelantado” or military commander, for Almagro; and the bishopric of Tumbes for Luque. Ruiz de Estrada would get the title of “alguacil mayor,” an ancient title meaning bailiff and a high office charge. The thirteen crew members of the last expedition would receive bonuses in addition to paid functions.

In early September 1528, when all was agreed, Pizarro boarded a ship from the port of Nombre de Dios on Tierra Firme’s Caribbean coast. With him were the young boys Felipillo, Yacané and Martinillo whom he had captured off the Island of Salango; the ship also carried half a dozen llamas, fine painted ceramics and embroideries, and much gold and silver. Pizarro landed at the Spanish port of Sanlúcar and went on to Seville. There, the lawyer Martin Fernández de Enciso recognized Pizarro as Alonso de Ojeda’s former lieutenant, accused him of having connived with Pedrarias Dávila in Balboa’s trial and execution, and demanded that he be jailed.

Someone at Court in Madrid, probably Pizarro’s brother Hernán demanded, through the Council’s office, that he be released on grounds of unsustainable facts and falsehood. In Madrid, Pizarro met with members of the Royal Supreme Council of the Indies, where he presented his written accounts and the maps of his voyages of discovery to Queen Isabela.I (1451-1504). He presented the tumbisinos Felipillo, Yacané, Martinillo and showed the llamas, the finely embroidered fabrics, and the gold and silver. The Royal Council was stunned by the news of this unknown world they named Nueva Castilla. A formal agreement or capitulación was then drawn giving Pizarro the titles of Captain General, Governor, Administrator (Adelantado), and Constable (Alguacil Mayor) over New Castille’s 200 leagues (700 miles). This area would henceforth be called Perú. Pizarro would receive an annual remittance of 725,000 gold maravedis (+/-$240K); Almagro was named Mayor and Constable of Tumbes, renamed Nueva Valencia de la Mar del Sur, with 300,000 maravedis and the honorific title of “hidalgo” or gentleman; Bartolomé Ruiz was named first navigator of the South Seas with 60,000 maravedis; Pedro de Candia, was elevated to the rank of artillery major of Perú and councilor of Tumbes, while the thirteen sailors were granted the status of knights of the Golden Spur with related benefits.

Under the terms of the agreement, Pizarro was authorized to set up towns with good soil and clear running water to grow food; name town mayors; mine gold and silver; build forts and organize military forces of 250 men; import horses and slaves; protect and evangelize the natives. Queen Isabela.I signed this Capitulación de Toledo or Agreement of Toledo, on 6 of July 1529. Once the nominations and agreement were signed, Pizarro, now with the title of governor of Perú rode to Trujillo, his birthplace in the province of Extremadura. He enjoyed his extended family there for a few weeks, many of whom would follow him to the New World. They included his illegitimate brothers Juan and Gonzalo Pizarro, a half-brother, Francisco Martín de Alcántara, and several childhood friends. In early 1530, they all met in Seville with Crown officials assigned to follow Pizarro, who planned to sail from the port of Sanlúcar de Barameda, instead of the traditional port of Cádiz. His last-minute port change was to bypass the terms of his agreement and exit license, which required him to take 250 soldiers.

Pizarro’s brother Hernando smartly suggested that, with his family and friends, the number of men met the exit license requirements. Meanwhile, the partners in Panama, Almagro and Luque, anxiously awaited Pizarro’s arrival in Nombre de Dios. Almagro was angry because, in past correspondences, he believed that his partner had hoarded Perú’s three most important Crown titles. He was enraged that he wanted to break the “Perú Enterprise.” Luque told him that there had to be reasons that would be explained upon their partner’s arrival. Almagro tepidly welcomed Pizarro, who, perceiving his partner’s antagonism, told him that he had to accept the three titles because the Crown did not want to split the agreement between two or more holders. Therefore, he had to bow to the Crown’s demands or lose the deal. Pizarro then underlined that the “Perú Enterprise” terms of association of equal partnership remained unchanged. Almagro was mollified, and the partners started to organize the third expedition to Perú. As expected, arguments quickly arose between Almagro and Pizarro’s brothers, Juan, González, and Hernando, with whom Almagro never got along. The antagonism was again threatening to break the enterprise, but thanks to Pizarro’s authority and Luque’s conciliatory approach, Almagro remained.

In the following weeks, two ships arrived from Nicaragua loaded with Indian slaves, under the command of Juan Ponce de Leon and his partner Captain Hernando de Soto. For his support in the Perú venture, de Soto demanded the position of lieutenant governor. He further demanded, for Ponce de León discoverer of Florida (1513), a large portion of land with natives to conquer. Once Pizarro, Almagro, Luque and the others agreed on the terms of their association, they prepared the third expedition.

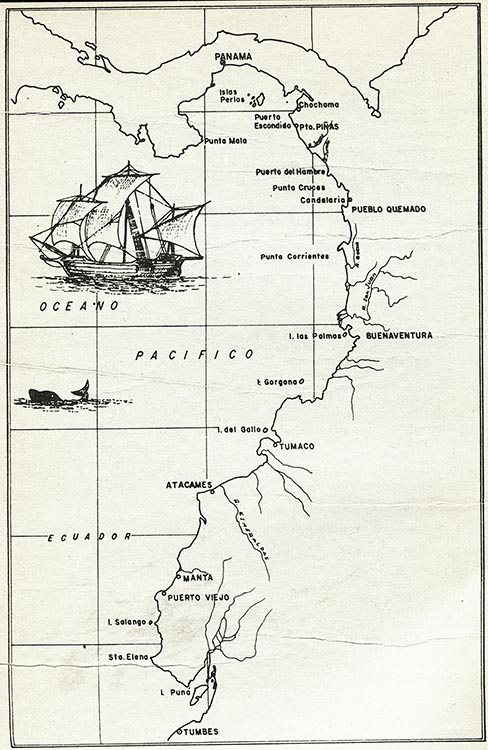

On December 27, 1530, the flags were blessed in Panama’s main church. The following day, Pizarro called for sailing within the next few weeks, and on January 20, 1531, they sailed to the Pearl Islands and then headed south with a good sea and winds. Besides its crew, there were 180 soldiers, support personnel, 36 horses, and war dogs. The second ship under Captain Cristóbal de Mena’s command was ordered to follow in early February.

Pizarro and his army landed on February 17 in a bay called San Mateo. While the second ship sailed further south, Pizarro, on horseback, accompanied by riders, headed inland along the coast. They entered the town of Atacames, where locals wore fine dresses. In the fishing town of Cancebi they met nobles wearing jewels of gold and saw precious ceramics and fishing nets. Tired, hungry, and under clouds of mosquitoes, they crossed the Quiximes Delta and, battling Coaque natives, found more gold and emeralds. Still heading south, and suffering from painful warts that crippled many, they stopped at a small village where they stayed from April 19 to September 11 to recover. In mid-September, a boat from Nicaragua arrived with reinforcements. The captain, Sebastián de Belalcázar, agreed to bring his men to join Pizarro’s troops, together with two of his friends, on condition that one be named aide-de-camp to Pizarro and the other the town’s mayor. With his sick army, Pizarro had no choice but to agree to the demands. With reinforcement, he proceeded south on a desert-like landscape of vast arid and sandy coastal plains interspaced by valleys and rivers of low water flow, seasonally fed by the snow melts from the snow melts of the Andes mountains.

In early October, after passing through Anta, Odon, and other small towns, and a place named Punta de Santa Elena, Pizarro rested his tired, thirsty, and hungry troopers. On Christmas Day of 1531, they met the Puna Island’s chief, Tumbalá, who brought them water and food, and invited them to visit his island. From past experiences of natives’ tricks hidden by smiles, Pizarro insisted he would only board the boat with the local chief, who was taken aback but accepted.

At this point, it is suitable to clarify who the people of Perú were in the sixteenth century. Today, the country is home to fifty-eight indigenous groups speaking forty-seven languages. The largest is Quechua, with Aymara a second but essential group, that together make up about a quarter of the country’s indigenous population. When the Spaniards arrived in the sixteenth century, there were more ethnic groups, each with their dialect, beliefs, customs, and antagonisms. Quechua was spoken in the kingdom’s capital, Cusco, called “Land of Four Parts” or Tahuantinsuyo. It spanned a territory from today’s Ecuador to most of the northern part of Chile and the northwestern part of Argentina in the south. This mosaic of cultures and languages strained under the Incas’ iron-fisted authority, which fueled sporadic rebellions.

Pizarro understood the latent antagonisms but did not realize then the immensity, complexity, and cultural fragmentation of the Inca empire. His persistent distrust of unknown people was grounded in his experiences in sixteenth-century European wars, where defiance was the norm. On Puna Island, captive young men from other tribes confirmed his suspicions. Pizarro learned about an agreement between recent enemies, Tumbalá of Puna and Chilimaza of Tumbes. The latter secretly arrived at night with warriors to capture or kill the white bearded men who fought back savagely for their lives. The Spaniards were saved by the arrival of two ships and soldiers under the command of Hernando de Soto, who turned the tide.

The “war of succession” that had gone on in the mountains over the last few years indirectly affected the people of the coast, but they knew what was happening from families and friends. Inca officials seconded the chiefs of towns and cities to assist them in administering and overseeing the local political order. That is why it was found later that the Inca governor of Tumbes knew about Tumbalá and Chilimaza’s deep-seated antagonism. Under threat from the Inca, they were forced to cooperate and capture or kill the Europeans, who were unaware of the raging war in the country. In April 1532, with de Soto in Chilimaza’s light boats, the Spaniards boarded their ship and left the island, which they had renamed Isla de Santiago. They then sailed to Tumbes on the coast and left that city on May 16 of that year, leaving behind a squadron of soldiers, a Crown official and a priest. A week later, Pizarro and his men reached the town of Poechos, where its chief Maizavilca welcomed them. Over a few weeks, Pizarro’s informed him of his plan to build a city and a port on the coast a few leagues away at the mouth of the Río Chíra. This plan soured the chief’s welcome because he realized he would lose authority. Like other chiefdoms in the region, however, he wanted to shake off the heavy hand of the Sapa Inca in his affairs but realized that he might have welcomed a heavier hand that would weaken his kinglet powers. Maizavilca shared his concerns with other principals of townships in the Río Chira’s Valley, who agreed to persuade Pizarro to move up the mountains, where bigger prizes and gold awaited. The Indian chiefs’ double aim was to get the Spaniards out of their lands and hand them over to Inca Atahualpa’s army, encamped near Cajamarca, nine thousand feet up in the Andes Mountain range.

The Inca was informed of the progress of Pizarro’s army on the coast and sent a spy to ascertain that they were men and not, as Maizavilaca claimed, huiracochas, the messengers of Huiracocha, the foremost god in the Inca religious pantheon. The spy met Hernando Pizarro and understood he was Francisco Pizarro’s brother. He was fascinated by the barber who shaved men’s faces, and the tamer who, at will, managed horses and war dogs. He also found out that horses only ate grass, not meat, while war dogs ate meat, not grass. His most significant discovery was that the Spaniards were men, not huiracochas, and he reported his findings to the Inca Atahualpa, who understood Maizavilca’s duplicity and kept it in mind for later retribution.

Pizarro was still focused on building a town to settle European migrants. So, on July 15, 1532, he built the village of Tangarará on a promontory South of Poechos in the Rio Chira Delta, whose shores were covered with trees and grass. It would not be his last attempt at a permanent settlement. Pizarro’s thirst for gold had not dimmed despite his venture’s trials, hardships, and growing costs. At that time, he knew the riches were not on the coast but up the mountains in Cusco, where he said the city was covered with gold.

Persistent rumors by natives about war up in the mountains would not stop him. He promised the rope to warn would-be deserters in his crew, demanding to return to Tierra Firme. Unbeknownst to the Spaniards, over the last two years, the war of succession for the crown of the Tahuantinsuyo or “Land of Four Parts” had raged between Huayna Capac Inca Yupanqui’s two sons, Atahualpa and Huascar. This tragic chapter of Perú’s history will be narrated in “The Fall of Cusco.”

This is the second of a two-part article – Read Part One Here

Photo credits:

Ph.5 – Queen Isabela.I of Castille Museo del Prado, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

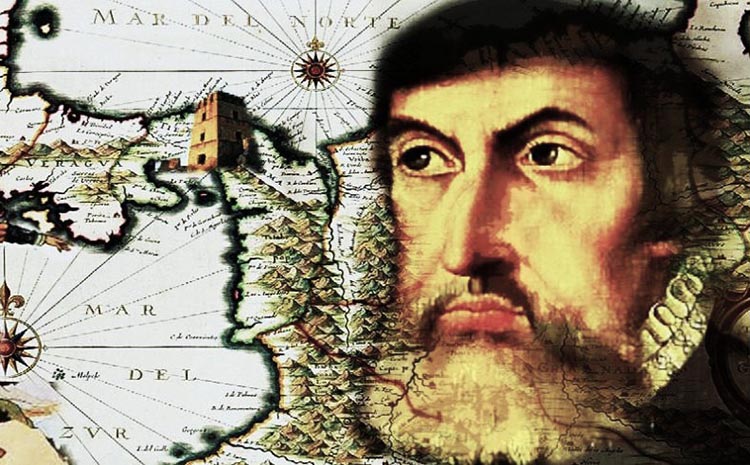

Ph.6 – Francisco Pizarro Ph.Amable-Paul Coutan, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ph. 7 – Hernando de Soto Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Contributor’s Bio:

Freelance writer, researcher and photographer georgefery.com addresses topics, from history, culture, and beliefs to daily living of ancient and today’s communities of Mesoamerica and South America. His articles are published online at travelthruhistory.com, ancient-origins.net and popular-archaeology.com, in the quarterly magazine Ancient American (ancientamerican.com), as well as in the U.K. at mexicolore.co.uk.

The author is a fellow of the Institute of Maya Studies in Miami, FL instituteofmayastudies.org and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org. Also a member in good standing of the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org, the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org, the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. americanindian.si.edu, and the NFAA – Non-Fiction Authors Association nonfictionauthrosassociation.com.

Contact:

Georges Fery – 5200 Keller Springs Road, # 1511, Dallas, Texas 75248 – T. (786) 501 9692 – gfery.43@gmail.com and www.georgefery.com