Yucatan, Mexico

by Georges Fery

What makes Dzibilchaltún – one of the oldest settlement of the northwestern Maya lowlands of Yucátan in Mexico – so perplexing are the seven crudely made figurines found buried below the altar in what has become known as the Temple of the Seven Dolls. At its peak, Dzibilchaltún which means “where there is writing on flat stones,” was a large and complex community, “engaged in the exploitation of nearby coastal resources, especially salt, and long-distance trade inland and marine.” It had more than “8,000 buildings spread over twenty square miles, most of which are one or two rooms platforms that once supported pole-and-thatch dwellings. Its population may have reached 20,000 souls; at that time, it was the biggest city on the peninsula” (Kurjack, 1979 in Andrews, 1980).

Located 7.5 miles from present day Mérida, and seven miles from the coast, Dzibilchaltún’s earliest recorded permanent settlement dates from the Early Formative pre-Nabanchè phase.1, 900BC. It was continually occupied from the middle to the late pre-Classic 500-250BC, with high and low occupation periods, up to the arrival of the Europeans in 1521. For the purpose of our story, we will focus on the city’s center and the Temple of the Seven Dolls, the easternmost major structure in the urban area where the figurines, or dolls, were found. Archaeologists refer to the temple as Structure.1-sub (Str.1-sub). It shares its spiritual powers with those of its westernmost counterpart, a temple known as Structure.66 (Str.66).

The program of investigation and restoration at Dzibilchaltún was initiated by E. Wyllys Andrews IV in 1956, with the sponsorship of the National Geographic Society and the Middle American Research Institute at Tulane University. The archaeological team realized that the 7,000 tons of collapsed ruble known was Structure.1 (Str.1) was irretrievably damaged and had to be removed, allowing for Str.1sub, which was below it, to be reclaimed. Str.1-sub was built on the base of an even earlier sanctuary, that was unlike those at other Maya sites in the Yucatán. The ancient city’s major structures and temples were painted with various bright colors, among which red was predominant. Str.1-sub, however, was painted white, and so was sacbe.1 surfaced with white limestone a “white road,” or raised causeway, that ended at the terrace in front of the temple. Traditionally, in an urban context, an east-west causeway covered with white stucco, was associated with the path of the sun. The Temple of the Seven Dolls was built on such an orientation. Of note is that the temple was named by archaeologists “Temple of the Dolls” while in all probability its ancient name was “Temple of the Sun.”

Str.1-sub is located on the easternmost side of Dziblichaltún, half a mile from the central plaza. The temple has four windows, unusual in Maya temples of that time, and two trapezoidal doors on both its east and west walls. There are two identical doors, but no windows, on the north and south walls. The importance of the play of light and shadows, that take place on March 21 and September 20 or 23 were strong indicators of the sun’s solsticial course. The first date signals the start of the seeding season, while the second that of harvesting. At that time, the sun god directed the priest-shamans’ seeding rituals in the temple. Its main doors and four windows on the east and west sides, and no windows on the opposite sides, underlines the temple sacred function.

Rituals in ancient communities followed the agrarian cycles under the auspices of their respective deities. The first sanctuaries were built for these mediators between the world at large (nature) and humankind (culture), because culture could not, on its own, control nature. Priest-shamans had to ensure the accuracy of the sun (K’inich Ahau, the sun-faced lord), which never failed to reappear at the exact same place, day after day, solstice after solstice, equinox after equinox. Priest-shamans were helped in their tasks by supplication and invocation rituals during which they addressed the deities of the vegetal world and the powerful god of rain.

Rituals in ancient communities followed the agrarian cycles under the auspices of their respective deities. The first sanctuaries were built for these mediators between the world at large (nature) and humankind (culture), because culture could not, on its own, control nature. Priest-shamans had to ensure the accuracy of the sun (K’inich Ahau, the sun-faced lord), which never failed to reappear at the exact same place, day after day, solstice after solstice, equinox after equinox. Priest-shamans were helped in their tasks by supplication and invocation rituals during which they addressed the deities of the vegetal world and the powerful god of rain.

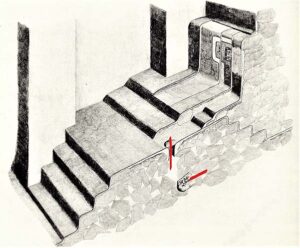

Solsticial and equinoxial movements were closely observed, but as important was the sun’s zenith event, that is when the sun reaches the observer’s zenith, 90° above the horizon, which only happens between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. Contreras offers an interesting hypotesis for monitoring this episode. “The high ceiling of the inner room of Str.1-sub forms a tower projecting above the temple roof. Str.1-sub tower’s ceiling may have been made of a lighter material to allow for temporary removal in order to let the sun rays at its zenith to light up the floor of the central chamber below” (Jobbova et al., 2018)). Str.1-sub tower collapsed when Str.1 debris were removed in 1959, but its restoration shows a small doorway on the south side for access to its roof. At Dzibilchaltún’s latitude, the sun’s zenith at the spring solstice is traditionally associated with the beginning of the planting cycle and the rainy season.

The monitoring of the repetition of natural events was associated with the aforementioned “mind-made” deities, masters of the seasons and people’s subsistence. The character of the ceremonies, directed by priest-shamans under the auspices of the lords of the realm, were dedicated to the all-powerful rain god Cha’ak, second only in the pantheon to K’inich Ahau, the sun god. Was the Temple of the Sun conceived allegorically as the “anchor” of the sun with ceremonies and rituals traditionally associated with the seeding of the earth? Most likely.

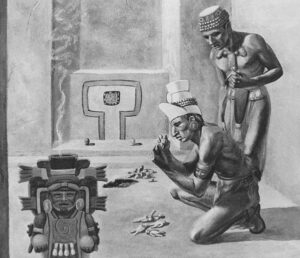

And so were the seven dolls, which were ritually “planted” by priest-shamans down a duct three feet deep, dug into the floor at the center of the temple’s altar. Bates Littlehales rendering (1959, in Andrews.1980) depicts the re-enactment of the ceremony of the seven dolls that took place during the Decadent Period’s Chechem Phase (1200-1500). The climate record for the Yucatán shows that this ceremony took place within the time frame of recurrent droughts.

And so were the seven dolls, which were ritually “planted” by priest-shamans down a duct three feet deep, dug into the floor at the center of the temple’s altar. Bates Littlehales rendering (1959, in Andrews.1980) depicts the re-enactment of the ceremony of the seven dolls that took place during the Decadent Period’s Chechem Phase (1200-1500). The climate record for the Yucatán shows that this ceremony took place within the time frame of recurrent droughts.

What was expected from rituals associated with the seven crudely made figurines? We do not know, and may never know. The figurines were described by archaeologists as displaying physical deformities. Andrews remarks “None of us had ever seen anything like them…we can only guess at their significance. Perhaps these little idols embodied the Maya priests’ formulas for curing disease” (1980). Of note is the fact that their number, seven, places them at the center of the culture’s spiritual world, at the intersection of the four cardinal directions, along with the zenith, the nadir, and the figurines’ position, believed to be the center of the community’s universe. The six females and one male figurines display oversized genitals (the male supports a disproportioned erect member). They are symbolic of the reproductive powers scattered by the sun, master of nature, a ritual found in many ancient cultures.

The disparity in gender, however, is puzzling and leads to the question: why six females and one male? Why not four and three, or other mix? Since there is no satisfactory answer from scholars, the next step was to ask respected local shamans (h’men) if they had any opinion on the gender disparity. One remarked, “one male and a number females in age of reproduction would secure the group’s survival, while conversely, one female among any number of males, would warrant its extinction” (2020). A stern observation that may be grounded in the survival of our species’ long lost past.

The disparity in gender, however, is puzzling and leads to the question: why six females and one male? Why not four and three, or other mix? Since there is no satisfactory answer from scholars, the next step was to ask respected local shamans (h’men) if they had any opinion on the gender disparity. One remarked, “one male and a number females in age of reproduction would secure the group’s survival, while conversely, one female among any number of males, would warrant its extinction” (2020). A stern observation that may be grounded in the survival of our species’ long lost past.

The figurines are not unlike those made by children, however, they are not “dolls.” Andrews note that “the tubular shaft at the bottom of which they were buried “psyco-duct” as we call it was not sealed but left open to, we assume, allow these spirits of the tomb to communicate their mysterious powers to the human world above” (1959:107-108). Placed at the very heart of the temple, the figurines may have been the guardians to the portal of the “otherworld,” the place where eternal life rises over death.

Scattering rituals were coincident with climatic stress during periods of decreased rain or drought. Is there a correlation between these age-old rituals and the figurines? Probably, because there is no other rationale for the priest-shamans to literally “plant” these deformed crudely made figurines below the floor of the temple’s altar. Their association with nature is symbolically linked with the roots of plants synonymous with the roots of life, for the figurines were made to never been seen. Furthermore, the scattering of human seeds was still practiced by farmers during the late nineteenth century in parts of the Americas. It was believed to periodically reaffirm a common law of the “right of blood” for farmstead inherited from ancestors, as opposed to the “right of land” claimed by invaders.

Scattering rituals were coincident with climatic stress during periods of decreased rain or drought. Is there a correlation between these age-old rituals and the figurines? Probably, because there is no other rationale for the priest-shamans to literally “plant” these deformed crudely made figurines below the floor of the temple’s altar. Their association with nature is symbolically linked with the roots of plants synonymous with the roots of life, for the figurines were made to never been seen. Furthermore, the scattering of human seeds was still practiced by farmers during the late nineteenth century in parts of the Americas. It was believed to periodically reaffirm a common law of the “right of blood” for farmstead inherited from ancestors, as opposed to the “right of land” claimed by invaders.

Archaeological data reported in Science (2018), show repeated phases of drought in the paleoclimate record from sediments in Lake Chinchancanab on the Yucatán peninsula. During the Maya Classic period (600-900), “…annual rain decreased between 41% and 54%, with intervals of up to 70% rainfall reduction during peak drought conditions” (Evans et al, 362:498-501). Furthermore, Metcalf and Davis, in Science & Public Policy Institute (SPPI, 2012), reported that “dry conditions, probably the driest of the Holocene, are recorded over the period 700-1200” (2007). Catastrophic natural events, and droughts in particular, were ascribed to the actions of malevolent deities that punished members of the priesthood and the nobility, who were at times overthrown as failed agents for their lack of devotion. “Planting and rain-beckoning rituals are a very common way in which past and present human communities have confronted the risk of drought across a range of environments across the world” (Jobbova et al, 2018).

Both Merida and Dzibilchaltún are located inside the Chicxulub crater created by the impact of the asteroid that struck the earth within the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) time-frame (66MYA), and caused the extinction event of the mega-fauna. The chain of cenotes or sinkholes, in this part of the peninsula is clustered outside the circle of the 93-mile impact zone, with a much smaller number found inside. In ancient agrarian societies, bodies of water, besides being vital to life, were at the heart of their religious beliefs and rituals because water was understood to be the essence of all life forms. Cenote Xlacah, (“old town” in Yucatec) is a major surface sinkhole at Dzibilchaltún. It was essential to the life of the city and its neighboring communities, given the lack of rivers in northern Yucatán and within the Chicxulub crater in particular. Xlacah’s surface area is bigger (328 feet x 657 feet) than the Sacred Well at Chichén Itzá (164×200 feet x 65 feet deep).

Within this mythological context, Xlacah was perceived as the anchor of the permanence and persistence of life, mediator of the nature-culture dichotomy found in the beliefs of ancient societies. In addition to Xlacah, over “ninety-five man-made wells were found in Dzibilchaltún’s twenty-plus square miles populated area” (Kurjack, 1974). They were mostly hand-dug holes, since the water table is but a few feet below the surface. Unlike small wells, however, large cenotes are replenished by circulating underground water, and cleaned by schools of tiny fish and aquatic plants. Located at the southwestern corner of the Central Plaza, Xlacah represents, in Coggins report “…the south and down, or the entrance and exit from the waters of the underworld” (1983:49-23). At its bottom, Xlacah’s floor slopes sharply down then levels off, continuing to an unknown distance in pitch blackness.

The cenote was the focus of rituals, as attested by more than 3,000 broken ceramic and water jars found at its bottom, together with portions of at least eight human skeletons and animal bones. Its waters were used for both daily needs and rituals that did not involve human or animal sacrifice. The few human remains found, therefore, were probably due to people that drowned while collecting water. Surface and underground cenotes are mirrors of two worlds, understood as the home of Cha’ak “patron of agriculture and one of the oldest continuously worshipped god of ancient Mesoamerica” (Miller+Taube, 1993). “Xlacah represent the center of Dzibilchaltún’s agrarian universe, its pivotal axis” (Lothrop, 1952, Tozzer, 1957). The powerful god of rain, lightning, and thunder was the master of life and fear, because should rain fail, the life giving maize harvest (corn-Zea mays subsp.) would wither, and lead to hunger, conflict and death. The Mayans have a deep reverence for maize for, in their mythology, the gods created them out of maize dough. It therefore is not only their main staple and daily sustenance, it is associated with their very existence, their soul.

The cenote was the focus of rituals, as attested by more than 3,000 broken ceramic and water jars found at its bottom, together with portions of at least eight human skeletons and animal bones. Its waters were used for both daily needs and rituals that did not involve human or animal sacrifice. The few human remains found, therefore, were probably due to people that drowned while collecting water. Surface and underground cenotes are mirrors of two worlds, understood as the home of Cha’ak “patron of agriculture and one of the oldest continuously worshipped god of ancient Mesoamerica” (Miller+Taube, 1993). “Xlacah represent the center of Dzibilchaltún’s agrarian universe, its pivotal axis” (Lothrop, 1952, Tozzer, 1957). The powerful god of rain, lightning, and thunder was the master of life and fear, because should rain fail, the life giving maize harvest (corn-Zea mays subsp.) would wither, and lead to hunger, conflict and death. The Mayans have a deep reverence for maize for, in their mythology, the gods created them out of maize dough. It therefore is not only their main staple and daily sustenance, it is associated with their very existence, their soul.

The half-mile causeway.1 runs in a straight line from the city’s central plaza to the Temple of the Seven Dolls. One hundred forty-three feet west of Str.1sub are three structures with two rooms each, built astride the causeway, that controlled the approach to the temple, together with a high defensive stone wall in front (now gone). Access was limited through two narrow passageways, between the central pair of rooms, a reminder of the sanctity of the temple. Four hundred and forty-five feet west of the defensive wall stood Structure.12 (Str.12), a four-stairway/six-steps quadrangular platform with an eleven-foot-tall limestone monolith, Stela.3. It was covered with stucco and painted with figures of the Maya pantheon, now lost to time. It is one of about thirty such monuments on the site and squarely faces the west side door of the Temple of the Seven Dolls. Its position relative to the temple, however, indicates that it was most probably used as a sighting device reciprocal to those of Str.1-sub for the observation of heavenly bodies. Of interest is the fact that, from an allegorical standpoint, structures were important but no more so than the play of light and shadows at dedicated times, such as at solstices and equinoxes. Following the path of the sun, the shadows had the same ritual value as that of structures or select natural landmarks.

Architecturally similar to Str.1-sub, Str.66 is radially symmetrical and is located at the western end of sacbe.2. However, it has not been restored, hence the limited information on both structure and remains. The similarity with the Seven Dolls complex, however, is striking and extends to Str.63 with a four-stairway/six-steps quadrangular platform and an eleven-foot limestone monolith, Stela.21, located 145 feet east of Str.66’s plaza, and built squarely on sacbe.2. Like Stela.3 to the east, Stela.21 was covered with stucco and painted with figures of the Maya pantheon, now lost to time. Andrews refers to Str.66 as “a mirror image of the Seven Dolls group” (1961), dedicated to the moon, counterpart to Str.1-sub, which was dedicated to the sun. Like the Temple of the Seven Dolls, it also had its access restricted by Str.64 and Str.65 which were built across its plaza.

Architecturally similar to Str.1-sub, Str.66 is radially symmetrical and is located at the western end of sacbe.2. However, it has not been restored, hence the limited information on both structure and remains. The similarity with the Seven Dolls complex, however, is striking and extends to Str.63 with a four-stairway/six-steps quadrangular platform and an eleven-foot limestone monolith, Stela.21, located 145 feet east of Str.66’s plaza, and built squarely on sacbe.2. Like Stela.3 to the east, Stela.21 was covered with stucco and painted with figures of the Maya pantheon, now lost to time. Andrews refers to Str.66 as “a mirror image of the Seven Dolls group” (1961), dedicated to the moon, counterpart to Str.1-sub, which was dedicated to the sun. Like the Temple of the Seven Dolls, it also had its access restricted by Str.64 and Str.65 which were built across its plaza.

The first sanctuaries were built for deities, mediators between an unmanageable nature and humankind, to persuade them through prayers and sacrifices to provide or facilitate food. From early human history, daily sustenance was an enduring concern. Dependence on the vagaries of the Yucatán’s seasons, climate, and the “mood of the gods,” kept communities in constant dread. Natural events such as, flood, drought, or insect plagues, brought constant fear, anxiety, and hunger. It is not surprising then that communities sought solace and help from their shamans, the needed go-betweens to commune with the overbearing deities of nature, to help people carry their unpredictable burdens.

For centuries, ancient gods and deities were the heartbeat of this great city and helped people cope with environmental stress such as drought, locusts, hurricanes, and other natural events. As is the case for all rituals and prayers, they helped people contend with an inherently unpredictable nature. The shadows of centuries inexorably blurred gods and deities, but below Str.1-sub altar, undisturbed by time and events, the Seven Dolls kept their relentless watch over Dzibilchaltún.

Photos/Drawings Captions and Credits:

- 12 and Stela.3 – ©georgefery.com

- Map of Dzibilchaltun – ©Andrews-MARI

- Temple of the Seven Dolls – ©georgefery.com

- The Dolls Cache.3 – ©Andrews-MARI

- The Seven Dolls – ©Andrews-MARI

- Dolls Burial, Reenactment – ©Andrews-MARI

- Cenote Xlacah – ©georgefery.com

- The Seven Dolls Complex – ©Edward B. Kurjack

Bibliography / References:

Edward B. Kurjack, 1974 – Prehistoric Lowland Maya Community and Social Organization, A Case Study at Dzibilchaltun, Yucatan, Mexico; and,

Willis Andrews.IV and E.W.Andrews.V, 1980 – Excavations at Dzibilchaltun, Yucatan, Mexico; and,

Clemency Coggins, 1983 – The Stucco Decoration and Architectural Assemblage of Structure-1.sub, Dzibilchaltun, Yucatan, Mexico.

MARI-Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA

Orlando Josué Casares Contreras, 2001 – Una Revisión Arqueoastronómica a la Estructura 1-Sub de Dzilbilchaltún, Yucatán – Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Merida.

Eva Jobbova, Christophe Helkme + Andrew Bevan, 2018 – Ritual Responses to Drought: An Examination of Ritual Expressions in Classic Maya Written Sources – Human Ecology

Mary Miller & Karl Taube,1993 – The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya

Evans et al, 362:498-501). Science (2018)

In 1995, Hodell, Curtis and Brenner published a paleoclimate record from Lake Chichancanab on the Yucatán Peninsula that showed an intense, protracted drought occurred in the 9th century AD and coincided with the Classic Maya collapse

About the Author:

Freelance writer, researcher, and photographer, Georges Fery (georgefery.com) addresses topics, from history, culture, and beliefs to daily living of ancient and today’s indigenous communities of the Americas. His articles are published online in the U.S. at travelthruhistory.com, popular-archaeology.com, and ancient-origins.net, as well as in the quarterly magazine Ancient American (ancientamerican.com). In the U.K. his articles are found in mexicolore.co.uk.

The author is a fellow of the Institute of Maya Studies instituteofmayastudies.org Miami, FL, and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org. As well as a member in good standing of the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org, the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org, NFAA-Non Fiction Authors Association nonfictionauthrosassociation.com, and the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. americanindian.si.edu.

More Stories About Yucatan Pyramids:

Looking for a Mexico Tour?

Sacred Pyramid Tour of Mexico

September 2 – 12, 2022

Hosted by Cliff Dunning of Earth Ancients

Offered by Body Mind Spirit Journeys

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.