This is the 2nd of three articles by Lee Ruddin about slavery in Liverpool and a walking tour of the city where evidence of Black History can now be seen.

See part 1 at https://travelthruhistory.com/liverpool-black-history-walking-tour-part-1/

FROM LIVERPOOL TOWN HALL TO ABELL’S MEMORIAL STONE

Standing/seated to the right of the portico entrance of the Town Hall that overlooks Castle Street, specifically beneath the unabashed iconography on the east façade situated on High Street, turn right (heading north-west) towards Exchange Flags: it’s here where merchants such as John Gladstone (father to the aforementioned William who was, according to the Legacies of British Slave-ownership project, the biggest claimant of government compensation for the loss of “property” after abolition in 1834) transacted business in the open air, author of Capitalism and Slavery Williams reiterates, selling ‘sugar and other produce […] grown on his own plantations and imported in his own ships’. When continuing along the rear (north side) of the building pause momentarily and try to imagine the bustling commercial activity on the site of today’s grandiose quadrangle. After peeling your eyes away from the Grade II-listed Nelson Monument, follow the building around to the left (its west side) before turning right back onto Water Street, stopping at its top outside Martins Bank (Numbers 4 and 6), a mere 160 metres away.

Address: Martins Bank Building, 4 and 6 Water Street, Liverpool, L2 3SP.

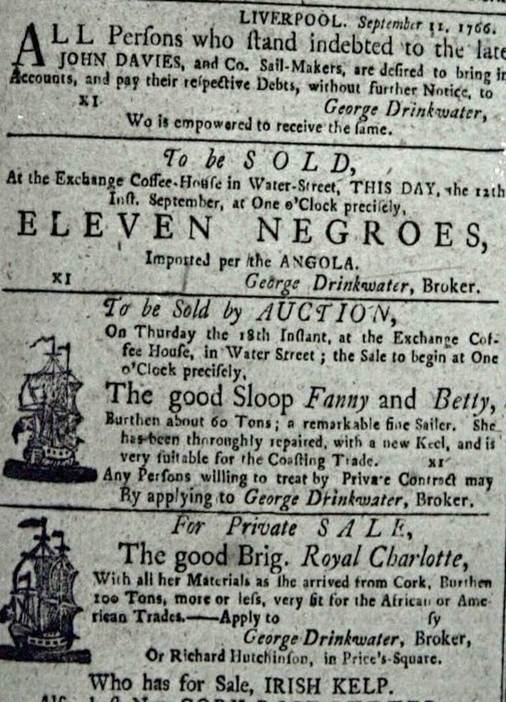

This is considered by some to be the probable location (listings conflict in Gore’s Directory, frustrating those desirous of pinpointing the exact spot) of Exchange Coffee House where, in 1766, 11 ‘imported’ Africans were advertised to be sold by a broker, literally illustrating that racial slavey wasn’t confined to the colonies but also evident in the metropole (Images 6 and 7), suffusing life in Liverpool like a fog: pervasive to the point of being omnipresent; the same could be said for “tools of the trade”, with hardware of bondage (ranging from restraining implements such as handcuffs and leg shackles to a speculum oris, the latter used for releasing jaws to force-feed captives) purchased from a ship chandler by the tenacious agitator Thomas Clarkson in 1787 while lodging at the King’s Arms tavern, formerly opposite the site of Martins Bank, where all matters mercantile were discussed. (Affixing a reinterpretation plaque at this site could draw the attention of passers-by away from sinners towards Clarkson who, assisted by one of the “Liverpool Saints” Edward Rushton, stands alongside William Wilberforce and Olaudah Equiano in the abolitionist pantheon.)

That a former building on the site of today’s Grade II-listed Martins Bank was called African House (No. 6) isn’t surprising given West Africa House is the name of a premises at the bottom of Water Street. Yet the Art Deco-style sculptures carved into a doorway (next to the main entrance) during the building’s redesign between 1927-1932 – more than a century after the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, it’s worth noting – are surprising since they indubitably celebrate the role slavery played in Liverpool’s meteoric rise from a third-rate fishing village to “Second City of Empire” thanks, Laurence points out, to being a constituent of Lancashire: the ‘first industrial region in the world’. [Laurence Westgaph is Historian in Residence for National Museums Liverpool.] They depict Liverpool as Neptune, who has his hands on the heads of African children, both of whom carry a bag of gold and either an anchor or weighing scales (or possibly a ship’s quadrant?) (Images 8 and 9). Whether or not renowned local sculptor George Herbert Tyson Smith was cognisant of the site’s history, the record is unclear, though its murky past provides some clarity regarding why such decorative panels adorn the exterior: the Bank of Liverpool acquired Arthur Heywood, Sons & Company (1773) in 1883 (one of the ten noteworthy banking houses founded in mid-to-late eighteenth-century Liverpool by slave merchants who pioneered credit supply for long-term ventures) before merging with London-based Martins in 1918 (to become Bank of Liverpool and Martins Limited before shortening its name a decade later). Martins, in turn, was absorbed by Barclays in 1969. They closed and relocated in 2007, the bicentenary of the 1807 Slave Trade Abolition Act, yet no plaque exists referring to its origins (or predecessors who facilitated and profited) in racial slavery despite memorialisation of oppression such as the above-described helping to undergird contemporary racism; even the handsome stone plaque affixed to the former Heywoods Bank in Brunswick Street (commissioned by Arthur Jnr. in 1800) omits any mention of the fact that founding brothers Arthur and Benjamin Heywood participated in the ugly trade, investing (according to the Slave Trade Database) in no less than 125 slave voyages between 1745-89.

Viewing the identical reliefs in the doorway from the vantage point of the photographer (Image 8), spin 180 degrees and head (south-west) down Water Street, passing Rumford Street and Convent Garden respectively, before taking the third right onto Tower Gardens. While narrow, and thus potentially hazardous due to a continual line of parked cars, this cul-de-sac affords the best access to the Grade II-listed Church of Our Lady and St. Nicholas (Image 10) for wheelchair users, being only 160 metres distant. A place of worship since at least 1257 (just fifty years after King John granted Liverpool its Royal Charter in 1207!), this venerable site is the most historic part of the city centre (regardless of the current incarnation – save the rebuilt nineteenth-century Tower – dating back only as far as 1952) where prominent slaving merchants worshipped and were interred, chief among them being slave-ship captain and two-time Mayor of Liverpool Bryan Blundell (d.1756), one of the many bigots with which the town was so well endowed. (His ship, The Mulberry, is believed to have been the first to sail out of Old Dock, the world’s first commercial wet dock opened in 1715, with the Blundell family going on to be involved in 109 slave-ship voyages.)

Address: Liverpool Parish Church of Our Lady and St. Nicholas, Old Churchyard, Chapel Street, Liverpool, L2 8TZ.

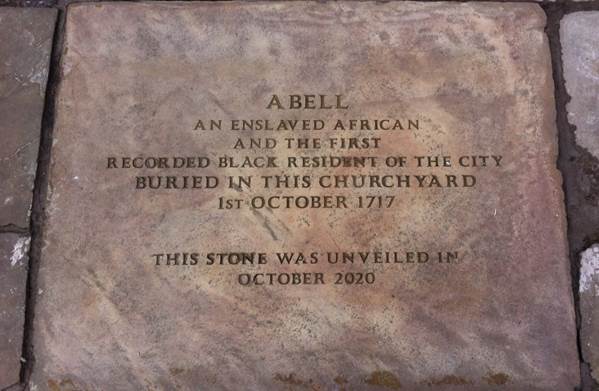

Approximately forty years before the co-founder of Bluecoat School was laid to rest, however, a person called Abell was buried in what’s nowadays a garden. According to the burial register unearthed by Laurence as part of his PhD research at the University of Liverpool, Abell, ‘A [B]lack[a]moor [a contemptuous term used to describe a dark-skinned individual] belonging to Mr. [Samuel, or Lemuel?] Rock’ (a slave trader for whom he almost certainly worked as a domestic slave-servant), is the first identifiable Black burial in Liverpool – Georgian Liverpool, no less – and is another “dark” tourism site like Sambo’s grave (an enslaved cabin boy buried, in 1736, at Sunderland Point near Lancaster, UK), as featured in Stone’s 111 Dark Places. Preoccupation with the infernal Middle-Passage leg of the triangular trade has led shore-based elements of enslavement to go largely unremarked upon, with slavery discourse framing the port as the start and end point for carrying what historian Jessica Moody refers to as ‘inanimate goods only’ in her monograph, which is entitled The Persistence of Memory: Remembering Slavery in Liverpool – ‘Slaving Capital of the World’ (2020). Yet Laurence’s sedulous study of parish records in order to name the hitherto unnamed, culminating in the creation of a memorial to Abell (Image 11), illuminates that the narrative propagating Black presence as a post-war phenomenon – beginning with the SS Windrush – is a whitewashing of history. (The first Black Liverpudlian, according to baptismal records says Laurence, was born in the 1750s.)

About the author:

A frequent ‘Letter of the Month’ winner in UK travel newspapers/magazines, Lee P. Ruddin’s entry in Senior Travel Expert’s 2018 (Heritage) Writing Competition was shortlisted as Highly Commended by judges; his entry in I Must Be Off’s 2020 contest was longlisted. His articles feature in Robert Fear’s Travel Stories and Highlights: 2019 Edition, on the websites of Hotel Metropole Hanoi and Bath’s Royal Crescent Hotel, as well as at TravelMag. In addition to tips appearing on theguardian.com, he has reviewed travel guides for LoveReading and NetGalley and, to date, has travelled in and via 45 countries on four continents. Born in Birkenhead on the Wirral in North-West England, he currently resides in Birmingham, where he works in the security industry.

All photos by Lee P. Ruddin

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.