Exploring the Atacama Desert on a Horse With No Name

by Paola Fornari

“What’s my horse’s name, David?” I ask my guacho guide.

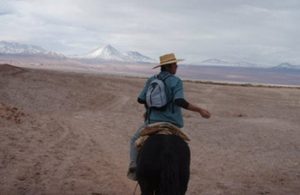

We are plodding along the valley floor of the Atacama desert towards the Cordillera de la Sal – the Salt Mountain Range. Behind us the Andes line the horizon, the icing sugar sprinkled Lascar and Licancabur volcanoes reaching up over fifteen thousand feet into the sky. It doesn’t surprise me that the Atacameño people used to communicate with the gods by talking to the mountains.

We are plodding along the valley floor of the Atacama desert towards the Cordillera de la Sal – the Salt Mountain Range. Behind us the Andes line the horizon, the icing sugar sprinkled Lascar and Licancabur volcanoes reaching up over fifteen thousand feet into the sky. It doesn’t surprise me that the Atacameño people used to communicate with the gods by talking to the mountains.

“She doesn’t have a name,” my guide replies. “Mine’s called India.”

“Hey David, what do you call a gaucho in Chile?”

“Huaco.” David is not a talkative type.

I settle down and enjoy the silence. As we start climbing up the dunes my horse suddenly gets a burst of energy and accelerates. I forget everything I ever knew about tightening reins, and my feet slide out of the leather half-clogs that are my stirrups. I call out, my voice echoing against the rocks ahead, and David comes to the rescue.

I settle down and enjoy the silence. As we start climbing up the dunes my horse suddenly gets a burst of energy and accelerates. I forget everything I ever knew about tightening reins, and my feet slide out of the leather half-clogs that are my stirrups. I call out, my voice echoing against the rocks ahead, and David comes to the rescue.

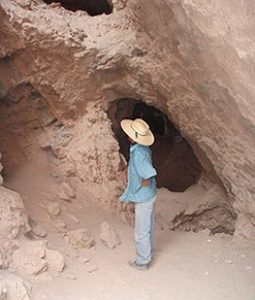

Soon, having accepted that my nag likes sprinting on the tangents, I feel she is more or less under control. We reach some small caves in the rock face. I copy David, dismounting and tethering my horse.

“Well done, huaca,” says David. “This is where miners used to dig for copper. They lived here with their families, in simple stone shelters, until 1900. They used to process the copper here, then carry it to San Pedro on mules, and exchange it for food.”

“Well done, huaca,” says David. “This is where miners used to dig for copper. They lived here with their families, in simple stone shelters, until 1900. They used to process the copper here, then carry it to San Pedro on mules, and exchange it for food.”

A far cry from Chiquicamata, the largest open-pit copper mine in the world which I visited yesterday, which has a surface area of eight million square meters.

“There’s still copper here,” David tells me, picking up a speckled green and brown stone, “but this area is protected now.”

I arrived in the Atacama Desert four days ago, and it rained. I’m not joking. It rained. San Pedro de Atacama is one of the driest places on earth. The average humidity is 35%, the skies are clear for 330 days a year, and there is very little rain, which generally falls over about three days in February. The winter temperature, although nearing freezing point at night, rises to over 70 degrees in the day, so I thought it would be a good choice for a few days’ escape from the wet Uruguayan winter.

San Pedro de Atacama in June is quiet. The few other tourists were young backpackers. When you find you are the only non-gap student around, it can make you feel either very old or very young. I opted for the latter.

San Pedro de Atacama in June is quiet. The few other tourists were young backpackers. When you find you are the only non-gap student around, it can make you feel either very old or very young. I opted for the latter.

The half hour’s rain on my first day fell as snow in the mountains, blocking the route to the highest geysers in the world. Was I disappointed?

Not at all: I’ve seen snow on the normally bare desert mountains. I’ve seen flamingos – three distinct types – on the Atacama salt lakes against a backdrop of a fiery sunset, and most important of all, I’ve been through the desert on a horse with no name.

If You Go:

In San Pedro de Atacama there are innumerable cheap hostels. If you are looking for a little more comfort, you could stay at the following hotels:

Hotel Casa de Don Tomas: www.dontomas.cl

Hostería San Pedro: www.chilesat.net

Altiplanico: www.altiplanico.cl

Hotel Kimal: www.kimal.cl

Tierra Atacama www.tierraatacama.com

There are several daily flights from Santiago to Calama, which is 100 kilometres from San Pedro de Atacama.

Atacama Desert – San Pedro – Tours Now Available:

Private Afternoon Tour Moon Valley from San Pedro de Atacama

The Atacama Salt Flats and Toconao

El Tatio Geysers Tour from San Pedro de Atacama

Atacama Desert Stargazing Tour

Geisers del Tatio and Pueblo de Machuca Tour from San Pedro de Atacama

About the author:

Paola Fornari has lived in almost a dozen countries over three continents, speaks five and a half languages, and describes herself as a “roving expat”. She explains her itinerant life by saying: “Some lead; others follow.” Wherever she goes, she makes it her business to get involved in local activities, explore, and learn the language, thus making each new destination a real home.

Blog: www.writelink.co.uk/blogs/Chausiku

Photo Credits:

San Pedro de Atacama, Chile byPhoto by Vinícius Henrique Photography on Unsplash

All other photos are by Paola Fornari.