by Emma Jacobs

We arrived in Bandiagara, at the edge of the region, before dawn in the dusty lot of the bus station. We had been on the bus from Bamako, Mali’s capital, for twelve hours. Around us, men were dispersing and the families with children were settling down to rest in the dusty terrain of the bus depot until morning. We looked around us, more than a little clueless. The night was pitch black.

A motorcycle came roaring up out of the dark. Its light was blinding, but it honed in on us and approached swiftly. A man descended from it and approached us. Mamadou Traore would be our guide in Dogon Country.

A motorcycle came roaring up out of the dark. Its light was blinding, but it honed in on us and approached swiftly. A man descended from it and approached us. Mamadou Traore would be our guide in Dogon Country.

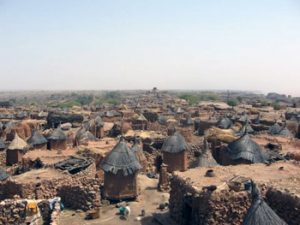

Dogon Country denotes a region of roughly 400,000 hectares, following the Bandiagara Escarpment, an astonishing line of cliffs which climbs up to 500m at its highest points in 150 km. The stunning views from the top went for miles. Savannah went all the way to the horizon, or sand, or rock. The area felt at times impossibly remote, but it was one of Mali’s first tourist groups. Mamadou was one of a few dozen guides who led Americans and Germans and French tourists along the Dogon cliffs each year.

Mamadou had been leading groups through Dogon country for 15 years. Two years ago, he led at Italian on a hike who was so grateful that after he returned home he made Mamadou a website to help other tourists find him. Mamadou checks it every time he comes back to Bandiagara. A town of more than 10,000 people, it has one internet café a mile from the bus station where we’d arrived.

Mamadou had been leading groups through Dogon country for 15 years. Two years ago, he led at Italian on a hike who was so grateful that after he returned home he made Mamadou a website to help other tourists find him. Mamadou checks it every time he comes back to Bandiagara. A town of more than 10,000 people, it has one internet café a mile from the bus station where we’d arrived.

Mamadou would lead us across the expanses of desert and rock and take us up and down the traditional Dogon stairways, cascades of stone down crevices in the cliff face. Dogon women climbed right past us with buckets of water on their head. One woman had a basket on her head and a baby on her breast. Mamadou did all the climbing in a pair of blue flip flops.

The region’s inhabitants mostly belong to the Dogon and Peul ethnic groups, but is identified exclusively with the Dogon, who began arriving from elsewhere in the 15th century. Before the Dogon, the Tellem lived in the Bandiagara cliffs from the 11th century, constructing the top line of shelters bored into the cliffs. In Dogon stories, Tellem may figure in, sneaking back to the Bandiagara escarpment, though no one sees them. A thorough archaeological exploration from the years 1964 to 1971 definitively found evidence of the presence of this Dogon myth.

The Tellem were agriculturalists, traditionally believed to be unusually small, who stored their food and buried their dead in caves high up the face of the cliffs. Caves have been discovered with the remains of up to 3000 people. One theory, ascribed to by our guide, suggests the Tellem ascended the cliffs on vines back when the valley was greener.

The Tellem were agriculturalists, traditionally believed to be unusually small, who stored their food and buried their dead in caves high up the face of the cliffs. Caves have been discovered with the remains of up to 3000 people. One theory, ascribed to by our guide, suggests the Tellem ascended the cliffs on vines back when the valley was greener.

Today, Dogon country is dry. The average in 1994 was only 600mm of rain, and droughts generally last 8 months of the year. Desertification has only worsened with scrub clearance. The temperature nears 120 in the summer, when Mamadou takes a few months off. It’s too hot for the hike.

The Tellem disappeared gradually from the valley after the 15th century, forced out by raids, and perhaps by a change in climate. The Dogon are believed to have migrated from the east—their oral history says from the land of Mandé —to this extreme region to escape the spread of Islam, which threatened animist traditions. The Dogon were agriculturalists from the start and arrived and settled in small groups, often isolated from each other. They often constructed their original villages some ways up the cliff walls. The buildings they erected on the sides of the Bandiagara cliffs were built of stones and mortar. The Dogon constructed mainly houses, but also granaries.

The Dogon cultivate rice, millet and sorghum. We would come upon fields of green onions for export to Bamako, a startlingly brilliant green in all that desert. The villages halfway up the cliffs had been gradually abandoned for more accessible terrain below closer to the crops and to available water supplies.

Today the Dogon villages are arrayed along the tops and bottoms of the cliffs. The villages are small and often long distances from each other. There are at least 15 dialects of Dogon today, some of which defy the comprehension of other Dogon speakers beyond the basic, rhythmic greetings.

Above certain villages on the cliff tops, Mamadou showed us crevices in the rocks where masks are stored. The Dogon would fascinate colonial anthropologists and archaeologists, the first European travelers to write accounts of Dogon Country, most of all intrigued by Dogon ritual and exquisitely carved masks. The Sigui ceremony, held every sixty years, is best-known of these rituals and occasion for some of the most elaborate masks. Researchers suggest Dogon culture is fluid and “accumulative” and these festivals could have changed over the many years of their continuation.

Above certain villages on the cliff tops, Mamadou showed us crevices in the rocks where masks are stored. The Dogon would fascinate colonial anthropologists and archaeologists, the first European travelers to write accounts of Dogon Country, most of all intrigued by Dogon ritual and exquisitely carved masks. The Sigui ceremony, held every sixty years, is best-known of these rituals and occasion for some of the most elaborate masks. Researchers suggest Dogon culture is fluid and “accumulative” and these festivals could have changed over the many years of their continuation.

Mamadou told us the first tourists to Dogon Country arrived in the 1970s. The interest in Malian antiques began during the same period and the leakage of the country’s national heritage to foreign parts worsened. The head of Mali’s national museum, Samuel Sidibe, has decried the systematic looting of the Bandiagara caves for tellem artifacts for resale to foreign antiquities dealers. Efforts have been made to organize and educate local populations and outlaw the export of Malian artifacts, but the fight is a difficult one in a very poor region in one of the world’s poorest countries.

We were told that the Dogon guides had been put in place to control the influence of the tourists on the Dogon villages. What’s mentioned most often is that the tourists gave the children things, candy and toys, and that their elders fear what will happen to the children’s work ethic.

Granting the validity of their parent’s concern, Dogon Country was also one of the most visibly suffering regions I saw in West Africa: villages where there were more children than not had distended bellies, others where there was only well water, and one village where the well water was such a dark, muddy yellow color that not even the bravest of our group would try to drink it with only our chlorine tablets.

The Cliffs of Bandiagara were named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1989, but the most obvious benefit this seems to bring is more tourists. Our guide helped us climb up to the lowest level of Dogon homes embedded in the cliffs. Walking though the abandoned villages, the structures date back centuries, but still appear virtually untouched. We passed through certain of the doorways and stood inside. At one point, our guide pointed us to a burial site, where a hole had been punctured through the walls. There were bones inside. Bowls and shards of pottery lay abandoned in the rooms of the homes.

The Cliffs of Bandiagara were named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1989, but the most obvious benefit this seems to bring is more tourists. Our guide helped us climb up to the lowest level of Dogon homes embedded in the cliffs. Walking though the abandoned villages, the structures date back centuries, but still appear virtually untouched. We passed through certain of the doorways and stood inside. At one point, our guide pointed us to a burial site, where a hole had been punctured through the walls. There were bones inside. Bowls and shards of pottery lay abandoned in the rooms of the homes.

Mamadou mentioned with pride the restorations of the cliff dwellings taking place with funding from UNESCO. Some of the buildings on the cliffs have undergone retouching. A man with a clipboard would approach us back in Bandiagara at the end of the week with a survey on sustainable tourism. Mamadou seemed unimpressed. Tourists have been coming to this region for thirty years, he told us. The region didn’t need that study.

When the World Heritage program made its case for the significance of the Cliffs of Bandiagara back in the late ’80s, its report cited the cliff cemeteries and Dogon stairways, but the writer of the essay go on to cite the living Dogon cultural history embedded in this region. You can feel it just beneath the surface, an accumulation of many years of tradition and change.

If You Go:

The Lonely Planet Guide to Mali is an essential on this trip. Visitors usually arrive in Mali’s capital, Bamako. From there, the bus ride to Dogon Country takes about 12 hours. Travelers willing to spend a little more can purchase the services of a vehicle and driver. In Dogon Country, guides can be hired in one of the larger towns you will arrive in. Once you’ve worked out an agreement, they’ll help find your meals and lodging at one of the many encampments scattered throughout the area villages. Hikes cease during the hottest months, beginning around April or May.

About the author:

Emma Jacobs is a student and mostly radio journalist currently based in New York City. She’s finishing up a degree in history and planning her next trip overseas.

Photo Credits:

Bandiagara Escarpment, Mali by Ferdinand Reus from Arnhem, Holland / CC BY-SA

All other photos are by Emma Jacobs.