Fort Langley, British Columbia

by Julie H. Ferguson

New Fort Langley, 20th Nov. 1858 – Yesterday the birthday of British Columbia was ushered in by a steady rain, which continued perseveringly throughout the whole day.

– The Victoria Gazette, November 25, 1858.

Rain pours down and the chill creeps into my bones as I trudge up the hill, past a statue of James Douglas. I splash through the gate in the tall palisade at Fort Langley towards the Big House. I have come to participate in the 151st anniversary of the founding of British Columbia and the swearing-in of James Douglas as the colony’s first governor. I’m alone. No one has come on the day itself for it is a soggy Thursday – the main celebration is on Saturday.

The gloom of this wet November day in 2009 helps me imagine Douglas’s impression on arriving at the place he knew so well – clouds obscuring the mountains, bare trees, and muddy paths. The sole splash of colour in this monochrome scene of grey and black is my pink umbrella. Just one person is braving the weather in the heart of this former Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) fort and trading post. She is a First Nations volunteer wrapped in a blanket. “Miserable weather,” she sniffs, peering at me from below her woven cedar hat. Today, no Hudson’s Bay employees are working at their jobs that operated the fort – the blacksmith, coopers, cooks, labourers, clerks, and traders are gone now. No visitors either, I realize.

The gloom of this wet November day in 2009 helps me imagine Douglas’s impression on arriving at the place he knew so well – clouds obscuring the mountains, bare trees, and muddy paths. The sole splash of colour in this monochrome scene of grey and black is my pink umbrella. Just one person is braving the weather in the heart of this former Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) fort and trading post. She is a First Nations volunteer wrapped in a blanket. “Miserable weather,” she sniffs, peering at me from below her woven cedar hat. Today, no Hudson’s Bay employees are working at their jobs that operated the fort – the blacksmith, coopers, cooks, labourers, clerks, and traders are gone now. No visitors either, I realize.

I pause and consider what it was like on November 19, 1858. I can hear the constant drip of the raindrops and the squawking of a couple of Stellar’s Jays that Douglas also heard, but not the 13-gun salute fired by the SS Beaver anchored in the river. Nor can I hear the marching feet of the Royal Engineers’ honour guard clad in scarlet jackets as they led Douglas and his entourage into the fort and up to the Big House. The cooperage and smithy are shut and no Union Jack flies from the flagpole in 2009.

The warmth of the Big House is as welcome to me as it must have been to James Douglas. Today I stand in a faithful replica, the original house long gone. The wood lining the walls is not darkened by age and electric light dispels the dark day outside. Kerosene lamps would have brightened the interior for the 100 men squeezing into an average-sized room on the ground floor for the ceremony to proclaim the Colony of British Columbia. The organizers had hoped to hold it in the open air but the weather intervened. They did not transfer the event to the large hall upstairs that would have handled the crowd more comfortably because servants were preparing it for the celebratory dinner.

I wander in silence through the rooms of the Big House. On the ground floor, I see an office, a small kitchen, and the rest of the living quarters of the fort’s chief trader and his family all filled with furniture and items of the mid-1800s. Through the back window, the cookhouse stands silent. Upstairs, the large hall is now arranged, in part, as a trading post with displays of artifacts from 150 years ago. In Douglas’s day, the trading took place in another building within the palisade and was a lively business. The First Nations people brought the furs here and received trade goods in exchange. Favourite items are piled almost to the ceiling – blankets, bolts of fabric, sacks of flour, pots and pans, guns and ammunition, and axes. These goods travelled a long way in Douglas’s day. HBC brought them overland by canoe and pack horses from Montreal or York Factory on Hudson Bay, a hazardous journey that took many months of privation for the voyageurs.

I wander in silence through the rooms of the Big House. On the ground floor, I see an office, a small kitchen, and the rest of the living quarters of the fort’s chief trader and his family all filled with furniture and items of the mid-1800s. Through the back window, the cookhouse stands silent. Upstairs, the large hall is now arranged, in part, as a trading post with displays of artifacts from 150 years ago. In Douglas’s day, the trading took place in another building within the palisade and was a lively business. The First Nations people brought the furs here and received trade goods in exchange. Favourite items are piled almost to the ceiling – blankets, bolts of fabric, sacks of flour, pots and pans, guns and ammunition, and axes. These goods travelled a long way in Douglas’s day. HBC brought them overland by canoe and pack horses from Montreal or York Factory on Hudson Bay, a hazardous journey that took many months of privation for the voyageurs.

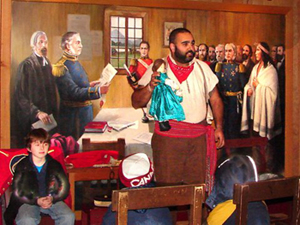

When I stand on the spot where Douglas had actually been sworn-in and reflect on what happened here, I hear strains of lively French Canadian fiddle music. My heart lurches – is it a ghost? No, it’s a volunteer hidden close-by adding atmosphere for the “Proclamation Play.” My reverie vanishes abruptly as 30 teenagers clatter into the room and take their seats to watch.

When I stand on the spot where Douglas had actually been sworn-in and reflect on what happened here, I hear strains of lively French Canadian fiddle music. My heart lurches – is it a ghost? No, it’s a volunteer hidden close-by adding atmosphere for the “Proclamation Play.” My reverie vanishes abruptly as 30 teenagers clatter into the room and take their seats to watch.

The play takes some dramatic licence with British Columbia’s birthday and the stories about James Douglas, but it certainly engages the students. The narrator portrays Douglas as a tough, rather unpleasant man. Of course, the truth is more complicated, but he certainly had difficulty adjusting to governorship after spending so many years influenced by the controlling ways of HBC. I remember other sides of Douglas’s character too. He loved children, was faithful to his wife, Amelia, treated the First Nations bands better than his peers did, and was a successful project manager. Intense and lacking humour, he often acted unilaterally as governor forgetting to consult the Legislative Council beforehand, which tarnished his stellar reputation in the fur trade. Douglas’s handling of the Fraser River Gold Rush that precipitated the British decision to create a Crown Colony on the mainland was dictatorial but mostly effective, and later his ambitious road-building schemes opened up the interior to colonization.

As I watch the play, whispers from that momentous day reach my ears. Douglas first swore-in the new Chief Justice Matthew Begbie. Then with great solemnity, Begbie read the proclamation that created the Colony of British Columbia and Douglas, its first governor. Douglas announced three edicts, the most important of which instituted English Common Law in the colony. Never one to smile, he maintained his familiar air of gravitas throughout.

As I watch the play, whispers from that momentous day reach my ears. Douglas first swore-in the new Chief Justice Matthew Begbie. Then with great solemnity, Begbie read the proclamation that created the Colony of British Columbia and Douglas, its first governor. Douglas announced three edicts, the most important of which instituted English Common Law in the colony. Never one to smile, he maintained his familiar air of gravitas throughout.

That evening Douglas and his associates enjoyed a formal dinner. In the hall, tables were laid with white linen and silverware, and crystal glasses sparkled in the light of many candles. The men feasted on salmon and venison as they talked about politics and the future. They drank many toasts to the new colony and Douglas; however, the toast to Queen Victoria moved Douglas the most as his new reality sank in – he was now her representative in, not one, but two jurisdictions at the outermost edge of her empire. Douglas admitted to his journal that he felt proud. Given his obscure beginnings as an illegitimate, part-Black man from British Guiana (Guyana today), he understated his reaction as he always did.

That evening Douglas and his associates enjoyed a formal dinner. In the hall, tables were laid with white linen and silverware, and crystal glasses sparkled in the light of many candles. The men feasted on salmon and venison as they talked about politics and the future. They drank many toasts to the new colony and Douglas; however, the toast to Queen Victoria moved Douglas the most as his new reality sank in – he was now her representative in, not one, but two jurisdictions at the outermost edge of her empire. Douglas admitted to his journal that he felt proud. Given his obscure beginnings as an illegitimate, part-Black man from British Guiana (Guyana today), he understated his reaction as he always did.

Next day, another ear-splitting 17-gun salute, this time from the fort, ricocheted around the cloud-draped mountains across Fraser’s River as the new governor left Fort Langley. Raising his hand in salute, Douglas climbed into a rowboat on his way to the ship that would return him to Victoria in the Colony of Vancouver Island, his other responsibility, and home.

In stark contrast, on my departure I am accompanied only by the loud dripping of the rain and my squelching footsteps, sounds James Douglas could not possibly have heard over the booms of the cannon honouring him and the newborn British Columbia.

If You Go:

The fort is a National Historic Site run by Parks Canada and is located in the town of Fort Langley beside the Fraser River in southern British Columbia. A dry day allows visitors the best opportunity to see the re-creation of a busy Hudson’s Bay Company fort and trading post. Volunteers, dressed in costume, re-enact life and work in the mid-1800s.

The quaint town of Fort Langley is well-worth a visit to enjoy the many cafes, antique stores, and boutiques.

Fort hours of operation:

7 days a week, year round; except December 25, 26, and January 1

Regular Hours: 10:00 am – 5:00 pm (September 2 – June 27)

Summer Hours: 9:00 am – 8:00 pm (June 28 – September 1)

Fort entrance fees:

Adult – $7.80

Senior – $6.55

Youth – $3.90

Family – $19.60 (Up to 7 people visiting together, with a maximum of two adults,)

Commercial Group, pre-booked – $6.55 per person

School Groups: Entry and a Heritage Presentation Special Program, per student – $3.90

School Groups: per student – $2.90

Much more visitor information is available at www.pc.gc.ca

How to get there:

Fort Langley National Historic Site

23433 Mavis Avenue, Fort Langley, B.C. Canada V1M 2R5

P: 604-513-4777

F: 604-513-4798

E: fort.langley@pc.gc.ca

W: www.pc.gc.ca

Maps:

Neither the Fort Langley website map at www.pc.gc.ca, nor Google Maps show the new Golden Ears Bridge across the Fraser River from Maple Ridge to Langley. For visitors arriving from the Tri-Cities and further east on the north side of the river, this is now the fastest route.

About the author:

Author and speaker, Julie H. Ferguson writes Canadian history for adults and teens. Her latest book is James Douglas: Father of British Columbia, a YA biography published by Dundurn, 2009. Julie has lived in British Columbia for forty years and is a member of Photoclub Vancouver.

She invites you to visit her author blog on James Douglas at www.jamesdouglasofbc.blogspot.com. Julie can be reached at info@beaconlit.com and also at her website at www.beaconlit.com.

Photo credits:

All photographs © Julie H. Ferguson 2009, except:

Photo #1 of the Big House, © M. Jassak (www.seefortlangley.com), with permission.

1. The Big House inside Fort Langley where British Columbia was proclaimed on November 19, 1858.

2. The statue of Sir James Douglas outside the fort. An identical one made from the same mold graces his birthplace in Guyana.

3. The dining room in the chief trader’s family quarters on the ground floor of the Big House.

4. Some trade goods given in exchange for furs. The most desirable were fabric, flour, kitchen utensils, axes, and guns.

5. The narrator of the Proclamation Play, Amn Johal, holding a doll that represented Douglas’s wife, Amelia. She did not attend the ceremony.

6. The mural in the room where the proclamation took place. Douglas is on the 2nd left holding the scroll. Beside him is Chief Justice of BC, Matthew Begbie who swore-in Douglas as governor.