Mt. Fuji, Japan

by Susan Elizabeth Thomas

There is an old Japanese proverb that reads, “He who climbs Mt. Fuji is a wise man; he who climbs twice is a fool.” I guess that makes me a fool.

After two years of teaching in Mito, Japan, I was ready to do something daring. I had become comfortable with the Japanese language and culture. Just living in another country made me feel more alive, so I was ready for another challenge. So I set out to conquer the tallest mountain in Japan with a few courageous friends and coworkers. Armed with a backpack of food, water and canned oxygen, I had one goal – reach the top by sunrise. I had no idea what we were in for.

Mt Fuji or Fuji san, is not just a mountain. It has a spirit. It is sacred in Shintoism, one of the main religions in Japan and has been venerated by the Japanese in art, poetry and stories for ages. The summit has a shrine dedicated to the goddess, Sengen sama, a goddess of nature. Whether for spiritual reasons or sport, over 100,000 people ascend every year. The first recorded person to climb Mt. Fuji was a monk in 663. Men frequently ascended the mountain in the following years, but women were forbidden until the 19th century. Nowadays, Japanese women not only brave the mountain, but some are rumored to climb it in heels. The shoe company Teva even branded some Japanese Yama Girl “mountain climbing heels” for these stylish, impractical climbers.

The mountain has ten rest stations. A bus can be taken to the 5th station, and the 10th is at the summit. Venders at the stations sell basic necessities: water, medical supplies, gloves and tissues. Several have small inns where visitors can nap and eat a small meal, usually ramen noodles. Some “inns” contain no more than tatami (straw) mat covered floors.

There are two ways to climb Fuji san. The most popular way is to climb up the mountain to the 7th or 8th station’s inn and sleep until a few hours before sunrise. This even gives you time to rest and even cook a small meal in a space oven. The other way is to climb up the mountain all night and down the next day without stopping. Guess which we opted for?

The spirit of Mt. Fuji had some surprises in store for us. The first hint this would not be a pleasant climb came when our leader, Daniel, informed us the weather forecast said “tokidoki ame” or “scattered showers.” Despite this news, our group headed into a large shop in the 5th station, with an air of naïve excitement. I put my valuables in a locker and purchased a souvenir wooden walking stick. Walking sticks can be branded for a few yen at each station. Each stamp is unique.

The spirit of Mt. Fuji had some surprises in store for us. The first hint this would not be a pleasant climb came when our leader, Daniel, informed us the weather forecast said “tokidoki ame” or “scattered showers.” Despite this news, our group headed into a large shop in the 5th station, with an air of naïve excitement. I put my valuables in a locker and purchased a souvenir wooden walking stick. Walking sticks can be branded for a few yen at each station. Each stamp is unique.

Our group started the trek, headlights illuminating the dirt path. Our walking sticks clacked against the rocks along the Yoshida trail. The Yoshida trail is the most popular of four paths up Mt. Fuji. Much of the initial slope has only a moderate incline. Later portions are steep and cut directly into the rock.

Our first problem occurred on our way to the 6th station. One member of our group, Helen, started to suffer from oxygen deprivation from the high altitude. After giving her a can of oxygen, I started to feel short of breath too. This worried me. I had suffered from asthma in the past, but I did not open another can of oxygen. I had heard if you start using oxygen at the beginning, you become reliant for the rest of the journey.

It began to rain. Splashing lightly at first, it was just enough to be uncomfortable. I soon realized Helen would not be able to keep up with our trek. She walked behind us slowly, almost stumbling, while sucking on oxygen. It would be dangerous for her to continue, so she agreed to stay in an inn for the night. The nearest inn seemed quite pleasant. Inns on Mt. Fuji become barer the higher you climb. After dropping off Helen, I returned to the station to brand my walking stick and rest.

The rain picked up and so did our speed. I thought we could be safe from the rain as soon as we were above the cloud line. In the rain and black of night, I could only see the ground directly in front of me. Not that there was much to see. Mt. Fuji is a barren rock with the exception of small ferns and moss after 2,500 meters. My group stopped for a rest at each station. The station workers stopped branding our walking sticks because of the rain. Shivering, I munched on some Calorie Mate bars, a Japanese meal substitute, jerky and whatever food I had brought with me. With my hands shaking in my gloves, I cracked the hardboiled egg I had purchased from a store, only to realize I had read the Japanese wrong. The egg was soft boiled and runny. I threw it down the mountain.

Maybe this angered Sengen-Sama. Next thing I knew, I was drenched, despite having raingear, and clinging to black, slippery rocks etched into the mountainside. The wind was strong. I worried one of us would be launched off the path in a strong gust. This was tokki dokki ame?

*“Fighting,” screamed the Japanese climbers up the mountain, “Fighting!” Clad in colorful climbing gear, their group ascended the mountain with the efficiency and timing of well-seasoned climbers. Our bedraggled group was different story. Trudging up the mountain and straight into the wind, my face was pummeled with rain drops. I could only hear the sound of the rain, the cries of the climbers and clacks of our walking sticks. The lights of Tokyo below were blotted out by the clouds. I leaned heavily on my walking stick as it made impressions in the red brown sludge. It was too late to go back. I treaded on.

After arriving at the inns, I was told they were all full for the night. When our group tried to take temporary refuge, old Japanese innkeepers barked at us to go away. I became envious of Helen with her oxygen deprivation and warm, sheltered inn. We were turned away from all shelters on the rock. It was back to the howling wind. If only we could get above the clouds, the rain will stop or so I thought.

Sadly, it continued to pour, even on the summit. The kind monks in the shrine gave us shelter from the rain. I bought charms of protection and health from them. I needed them. I huddled with the other climbers for warmth. The top of Mt. Fuji can be icy even in the summer. I wondered if I would get pneumonia. My friend was practically in tears, so I took to telling her jokes to keep her spirits up. But it was gray, all gray. The mountain, our mood and the sunrise were gray. With the coming sun, the dark charcoal sky turned to a slightly lighter shade. Trudging along, I began my wet descent.

With Mt. Fuji behind us, I rode public transportation back to my home in Mito, Japan. We must have looked strange to the commuters. Everyone in our group was dripping with water, caked in mud and aching from head to toe. Trails of dirt mapped our movements. I continued to rely on the support of our walking sticks while climbing the stairs in the subway. I had suffered from a minor case of altitude sickness on the way down the mountain. Sick and sleep deprived, I was able to sleep sitting, standing up or lying on the floor while waiting for the bus. Despite being dispirited, two of my friends and I agreed to try the climb again next year, when the experience was not as fresh in our minds.

With Mt. Fuji behind us, I rode public transportation back to my home in Mito, Japan. We must have looked strange to the commuters. Everyone in our group was dripping with water, caked in mud and aching from head to toe. Trails of dirt mapped our movements. I continued to rely on the support of our walking sticks while climbing the stairs in the subway. I had suffered from a minor case of altitude sickness on the way down the mountain. Sick and sleep deprived, I was able to sleep sitting, standing up or lying on the floor while waiting for the bus. Despite being dispirited, two of my friends and I agreed to try the climb again next year, when the experience was not as fresh in our minds.

One year later, I returned to Mt. Fuji with my two friends from the first group. Battered walking sticks in hand, I once again braved the mountain that had once threatened to throw me off. My group confirmed there was not even the slightest chance of “tokki dokki ame.” I branded my walking stick at every station. The trek was difficult but nothing like before. I climbed through the night and to the morning. Feet above the clouds, I gazed at a sky full of colors and the clouds below me. The barren rock shined in the new light. Blue, pink and gold clouds colored the sky. I was a fool, yes, but a fool with a good view.

Two years later, I sadly packed my belongings to leave Japan. Japan had been my home for so long, and I had to leave quickly due to rough personal circumstances. I had no idea how to get my Mt. Fuji walking stick on the plane. It was too long for my suitcases. Airport officials would not be amused if I took it through check in. But I did not want to part with it. The stick represented my determination despite the blackest of circumstances and physically grueling of challenges.

Two years later, I sadly packed my belongings to leave Japan. Japan had been my home for so long, and I had to leave quickly due to rough personal circumstances. I had no idea how to get my Mt. Fuji walking stick on the plane. It was too long for my suitcases. Airport officials would not be amused if I took it through check in. But I did not want to part with it. The stick represented my determination despite the blackest of circumstances and physically grueling of challenges.

I told my Japanese friend Hiroshi about my problems. With a twinkle in his eye, Hiroshi said he had a solution. He took my walking stick and returned the next day. He had cut it in half and attached a screw fitting on the end. I would be able fit my walking stick in my luggage and put it back together upon my arrival. I was so touched by his thoughtfulness. My memories of Mt. Fuji could be carried with me.

Leaving Japan was my Mount Fuji. It was hard and emotionally draining. Sometimes we can’t conquer mountains on our own. I did not need to be carried over the mountain, but I had needed the support of my walking stick. Only then could I reach the summit on my own two feet – through rain, sleet and sadness to the shining light of Mt. Fuji’s sunrise.

* “Fighting” is a Japanese-English expression that means, “Don’t give up.”

Mount Fuji Snow Climb Introduction to Mountaineering

If You Go:

Make sure you pack appropriately, as a climb up Mt. Fuji should not be taken lightly. Dress in layers, because it will get colder the higher you climb. Temperatures can be below freezing at the summit. Bring cans of oxygen, bottles of water, a reasonable amount of food, a headlight, toilet paper, rain gear and a rucksack with good support. Don’t forget to buy gloves and hiking boots with plenty of traction. You’ll need change for pay toilets and other expenses, like stamps for your souvenir walking stick. If you don’t want to buy a souvenir walking stick, I recommend bringing a different type. It will make the climb much easier.

You can take the Keio express bus from Shinjuku in Tokyo for 2600 yen. It’s also possible to take local trains to Fujinomiya or Gotemba, where you can take a direct bus to the 5th station.

If you want to stay at an inn, you might consider reserving a space in advance. The inns can fill up very quickly during peak season and situations involving bad weather.

When you descend Mt. Fuji, the incline is very steep. Most of your weight will shift to your toes and the balls of your feet. On a separate journey, one of my friends broke her toenail and had to limp down the mountain. So, make sure you properly cut your toenails, wear comfortable socks and broken in hiking boots.

Before you attempt the climb, it is a good idea to train lightly but consistently for several weeks before. This will make the trek much more enjoyable.

About the author:

Susan Elizabeth Thomas is an avid traveler, writer and lover of cultural anthropology. After four year in Japan, she is currently living in France. She hopes to give readers cause to question, discuss and deepen their understanding of this ever changing world. You can follow her writing through her blog (travelingmochi.wordpress.com), Twitter @TravelingMochi or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/TravelingMochi).

Photo credits (permission obtained for all photos):

The Shadow of Fuji by Kris J Boorman (www.facebook.com/kjbshoot)

All other photos by Susan Elizabeth Thomas

Fushimi Inari is a shine dedicated to Inari, the god of rice and his messenger the kitsune or fox. Fox demons are good omens in Japan, charged with warding off evil. These ethereal foxes can have multiple tails. More tails mean an older fox of greater power. Along with being messengers for Inari, who is often depicted as a large white fox, fox demons are tricksters. According to legend, foxes take humans forms for deceitful purposes. The cruel, proud and greedy were all targets. Often these crafty spirits became beautiful women. They would win the hearts of men and lure them from their families. Foxes were even known to bewitch humans, entering women under their fingernails or through their breasts.

Fushimi Inari is a shine dedicated to Inari, the god of rice and his messenger the kitsune or fox. Fox demons are good omens in Japan, charged with warding off evil. These ethereal foxes can have multiple tails. More tails mean an older fox of greater power. Along with being messengers for Inari, who is often depicted as a large white fox, fox demons are tricksters. According to legend, foxes take humans forms for deceitful purposes. The cruel, proud and greedy were all targets. Often these crafty spirits became beautiful women. They would win the hearts of men and lure them from their families. Foxes were even known to bewitch humans, entering women under their fingernails or through their breasts. I stepped into the courtyard at the base of the temple. My friend was not wrong. The place was completely empty. Or was it? Like many holy places, the shrine had a feeling of presence, eyes watching. There was nothing malevolent. I felt curious and excited. It was like entering another world, a very orange world. Fushimi Inari has thousands of orange torii gates. The sea of orange gates seemed to glow in the last light. Two fox guardians stood at either side of the entrance. It was hard to believe they were not watching.

I stepped into the courtyard at the base of the temple. My friend was not wrong. The place was completely empty. Or was it? Like many holy places, the shrine had a feeling of presence, eyes watching. There was nothing malevolent. I felt curious and excited. It was like entering another world, a very orange world. Fushimi Inari has thousands of orange torii gates. The sea of orange gates seemed to glow in the last light. Two fox guardians stood at either side of the entrance. It was hard to believe they were not watching. The whole shrine smelt of the evening and incense. I poured cold water from the small water basin onto my hands and into mouth. This is a Japanese ritual of purity, and I hoped that I was doing it correctly. I looked around. Hanging on lines, carefully folded, were the paper fortunes of hundreds of worshippers. Folding and hanging a paper fortune means you want it to come true.

The whole shrine smelt of the evening and incense. I poured cold water from the small water basin onto my hands and into mouth. This is a Japanese ritual of purity, and I hoped that I was doing it correctly. I looked around. Hanging on lines, carefully folded, were the paper fortunes of hundreds of worshippers. Folding and hanging a paper fortune means you want it to come true.

I felt uneasy when I heard the screeches in the dark. Something rustled in the bushes. Could it be foxes? Fox demons? I know now that it must have been monkeys, but things seem different in the dark. Paranoid, I started thinking about Japanese mythology. Crazy thoughts sprang up before my logical brain could dismiss them. What if the fox spirits possess me?

I felt uneasy when I heard the screeches in the dark. Something rustled in the bushes. Could it be foxes? Fox demons? I know now that it must have been monkeys, but things seem different in the dark. Paranoid, I started thinking about Japanese mythology. Crazy thoughts sprang up before my logical brain could dismiss them. What if the fox spirits possess me?

Dusk fell as we wound through a cypress grove filled with some half a million graves. The faithful have been buried here since the Kobo Daishi died in 835 AD. Famed as a poet, painter and calligrapher, and for bringing Shingon Buddhism to Japan, the Kobo Dashi is of the most revered figures in Japanese history. He sits in repose in his mausoleum, the Oko-in, where monks still bring him food twice a day.

Dusk fell as we wound through a cypress grove filled with some half a million graves. The faithful have been buried here since the Kobo Daishi died in 835 AD. Famed as a poet, painter and calligrapher, and for bringing Shingon Buddhism to Japan, the Kobo Dashi is of the most revered figures in Japanese history. He sits in repose in his mausoleum, the Oko-in, where monks still bring him food twice a day. The journey with the Kobo Dashi begins at a stone basin. Ubiquitous to Japanese temples, these basins overflow with running water, usually from a nearby stream. After ladling icy water over our hands, we bowed on crossing the graceful Ichinohashi Bridge; the Kobo Daishi then joined us. A lady in the shop opposite smiled and waved. The path then winds through the Okunoin, a grove of cypress and tombs. Tiny tracks stray from the main walkway, leading to even more tombs hidden in dells and forgotten grottos. The only sound was the chirping of crickets, or the ring of bells as white-robe pilgrims passed. Many of the tombs are simple stone plaques or wooden markers; others are the enormous mausoleums of shoguns. Animal shaped stones are popular, often with red cloths or little aprons tied around them.

The journey with the Kobo Dashi begins at a stone basin. Ubiquitous to Japanese temples, these basins overflow with running water, usually from a nearby stream. After ladling icy water over our hands, we bowed on crossing the graceful Ichinohashi Bridge; the Kobo Daishi then joined us. A lady in the shop opposite smiled and waved. The path then winds through the Okunoin, a grove of cypress and tombs. Tiny tracks stray from the main walkway, leading to even more tombs hidden in dells and forgotten grottos. The only sound was the chirping of crickets, or the ring of bells as white-robe pilgrims passed. Many of the tombs are simple stone plaques or wooden markers; others are the enormous mausoleums of shoguns. Animal shaped stones are popular, often with red cloths or little aprons tied around them. After a thirty-minute stroll, the track opens onto Oko-in, the Kobo Daishi’s temple. Suddenly the place bustles, for another path (almost a road) comes straight from the huge car park where the daily buses grind to a halt, delivering tourists intent on achieving enlightenment in a few hours. On this walkway can be found many gaudy (and theologically suspect) edifices, such as the White Ant Memorial, built as a guilt offering by a pesticide company.

After a thirty-minute stroll, the track opens onto Oko-in, the Kobo Daishi’s temple. Suddenly the place bustles, for another path (almost a road) comes straight from the huge car park where the daily buses grind to a halt, delivering tourists intent on achieving enlightenment in a few hours. On this walkway can be found many gaudy (and theologically suspect) edifices, such as the White Ant Memorial, built as a guilt offering by a pesticide company. Despite hosting over a million pilgrims a year, Koyasan remains a spiritual place. Most leave by mid-afternoon, and by evening we walked deserted streets. Many of the temples lie hidden behind wooden gates and guarded by stone lions, with the occasional glimpse of a balcony.

Despite hosting over a million pilgrims a year, Koyasan remains a spiritual place. Most leave by mid-afternoon, and by evening we walked deserted streets. Many of the temples lie hidden behind wooden gates and guarded by stone lions, with the occasional glimpse of a balcony.

My first stop is the hypocenter upon which sixty-six years ago, the world’s first atomic bomb was used against human targets. Aimed at the T-shaped Aioi Bridge near the geographic center of town, wind blew the bomb slightly off course some 500 meters to the southwest where it detonated over Shima Hospital.

My first stop is the hypocenter upon which sixty-six years ago, the world’s first atomic bomb was used against human targets. Aimed at the T-shaped Aioi Bridge near the geographic center of town, wind blew the bomb slightly off course some 500 meters to the southwest where it detonated over Shima Hospital.

I have a special Japanese friend serving as my informal guide on this trip. Her name is Koko, and she is a remarkable woman. She was just eight months old when Hiroshima was destroyed, so has no direct memory of that day. Yet the bomb has shaped and defined her life in many inscrutable ways. Standing not much more than four feet tall with salt-and-pepper hair pulled into a bun, she looks mild, but in relating the story of her journey from infant in the wrong place at the wrong time – the epitome of an innocent bystander – to peace activist and nuclear critic, she speaks with a stirring fervency, translating her Japanese into her own fluent, vivid English.

I have a special Japanese friend serving as my informal guide on this trip. Her name is Koko, and she is a remarkable woman. She was just eight months old when Hiroshima was destroyed, so has no direct memory of that day. Yet the bomb has shaped and defined her life in many inscrutable ways. Standing not much more than four feet tall with salt-and-pepper hair pulled into a bun, she looks mild, but in relating the story of her journey from infant in the wrong place at the wrong time – the epitome of an innocent bystander – to peace activist and nuclear critic, she speaks with a stirring fervency, translating her Japanese into her own fluent, vivid English. This is the pep block. There is almost no canned music at a Japanese baseball game. Instead, a bare-bones band leads the rabid fans whenever the Carp are up to bat. Bleating trumpets and pounding drums, elaborate sing-song chants with prescribed movements. The crowd cheers, “Bonzai!” then lapses into a pointed silence when the Tokyo Giants are up to bat. They reel their energy in again, least it accidentally offer encouragement to the other team. This is unrivaled in American sports anywhere; American sporting fans would be ashamed.

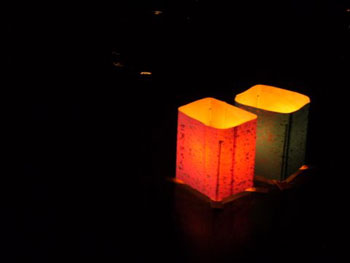

This is the pep block. There is almost no canned music at a Japanese baseball game. Instead, a bare-bones band leads the rabid fans whenever the Carp are up to bat. Bleating trumpets and pounding drums, elaborate sing-song chants with prescribed movements. The crowd cheers, “Bonzai!” then lapses into a pointed silence when the Tokyo Giants are up to bat. They reel their energy in again, least it accidentally offer encouragement to the other team. This is unrivaled in American sports anywhere; American sporting fans would be ashamed. There is a spiritual sense of communion, a union of the intimate and the universal found at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park this evening. The park is the site of the toro nagashi, or lantern ceremony, a traditional Japanese memorial service for the dead. It is by far the most moving part of the day. The skeletal A-Bomb Dome glows bright in the dark, its reflection dancing and shifting shape on the dark surface of the river like some Rorschach test of tragedy, an all-purpose steel and stone reminder of the fragility of even the most durable of man’s accomplishments.

There is a spiritual sense of communion, a union of the intimate and the universal found at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park this evening. The park is the site of the toro nagashi, or lantern ceremony, a traditional Japanese memorial service for the dead. It is by far the most moving part of the day. The skeletal A-Bomb Dome glows bright in the dark, its reflection dancing and shifting shape on the dark surface of the river like some Rorschach test of tragedy, an all-purpose steel and stone reminder of the fragility of even the most durable of man’s accomplishments.