Luxor, Egypt

by Dr. Benedict Davies

For the ancient Egyptians, the West Bank at Thebes (modern-day Luxor) was their realm of the dead, an august “City of the Dead”, no less. It was a sacred domain where the transition from this life to the next began. The whole area of this ancient necropolis is graced with funerary monuments, each specifically designed to facilitate a safe onward journey into the Underworld. Most conspicuous amongst these architectural treasures are the royal memorial temples, such as Deir el-Bahari, the Ramesseum and Medinet Habu. Located not far from these cultic installations were secluded cemeteries for the kings, queens and lesser royalty from the ruling dynasties of the Egyptian New Kingdom (c. 1550-1069 BC). And all along the fringes of the Theban Foothills, where the Nile Valley cultivation meets the desert, the most prominent officials of the age constructed their own tombs as portals into the hereafter.

One of the main highlights of Luxor is, without doubt, a tour of the royal necropolis, better known today as the Valley of the Kings. Here, amongst some of the most spectacular tombs from the ancient world, one can still come face-to-face with the mummy of the famous boy-king Tutankhamun in what had been a makeshift and hastily-prepared tomb. Bedecked with arcane hieroglyphic inscriptions and puzzling iconography, the magnificence of these sacred sepulchres has been enchanting and astonishing travellers ever since the earliest Greek and Roman historiographers found them long-abandoned and robbed of their spectacular burial treasures.

One of the main highlights of Luxor is, without doubt, a tour of the royal necropolis, better known today as the Valley of the Kings. Here, amongst some of the most spectacular tombs from the ancient world, one can still come face-to-face with the mummy of the famous boy-king Tutankhamun in what had been a makeshift and hastily-prepared tomb. Bedecked with arcane hieroglyphic inscriptions and puzzling iconography, the magnificence of these sacred sepulchres has been enchanting and astonishing travellers ever since the earliest Greek and Roman historiographers found them long-abandoned and robbed of their spectacular burial treasures.

Today most tour groups visiting the Theban west bank tend to combine the Valley of the Kings with a stopover at the memorial temple of the 18th dynasty female pharaoh, Hatshepsut. From afar, this temple’s magnificent edifice seems to have been hewn from the very cliffs of Deir el-Bahari by the gods themselves. If extremely lucky, your itinerary may allow you some time amongst the wonderfully decorated private tombs of officials that honeycomb the Theban hills. Yet, it is sadly regrettable that so few people find time to visit the ancient workmen’s village of Deir el-Medina. This remarkable site simply doesn’t register on the mainstream tourist ‘radar’. Yet, a visit to this wonderfully preserved settlement will be duly rewarded with a memorable experience.

Today most tour groups visiting the Theban west bank tend to combine the Valley of the Kings with a stopover at the memorial temple of the 18th dynasty female pharaoh, Hatshepsut. From afar, this temple’s magnificent edifice seems to have been hewn from the very cliffs of Deir el-Bahari by the gods themselves. If extremely lucky, your itinerary may allow you some time amongst the wonderfully decorated private tombs of officials that honeycomb the Theban hills. Yet, it is sadly regrettable that so few people find time to visit the ancient workmen’s village of Deir el-Medina. This remarkable site simply doesn’t register on the mainstream tourist ‘radar’. Yet, a visit to this wonderfully preserved settlement will be duly rewarded with a memorable experience.

Deir el-Medina was home to the royal artisans – the men who excavated and decorated the tombs in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens. For anyone interested in the history, architecture and art of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings, the village is something not to be missed, an opportunity to get up close and personal with the king’s own workmen. The remains of the ancient settlement lie in a secluded and dusty valley at the southern end of the Theban necropolis. The environment here is extremely harsh. Cut off from the cooling northerly breezes, the site is hot, arid and devoid of any vegetation. The modern Arabic name of Deir el-Medina refers to the Coptic monastery that was later founded on the site. “The Village”, as it was known to its ancient inhabitants, was a state institution, specifically established to house the royal craftsmen and their families.

Deir el-Medina was home to the royal artisans – the men who excavated and decorated the tombs in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens. For anyone interested in the history, architecture and art of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings, the village is something not to be missed, an opportunity to get up close and personal with the king’s own workmen. The remains of the ancient settlement lie in a secluded and dusty valley at the southern end of the Theban necropolis. The environment here is extremely harsh. Cut off from the cooling northerly breezes, the site is hot, arid and devoid of any vegetation. The modern Arabic name of Deir el-Medina refers to the Coptic monastery that was later founded on the site. “The Village”, as it was known to its ancient inhabitants, was a state institution, specifically established to house the royal craftsmen and their families.

The village appears to have been founded at the beginning of the 18th dynasty by king Amenhotep I (c. 1525-1504 BC). From then on the settlement underwent several phases of expansion to the extent that it comprised at least seventy family homes by the time of its eventual abandonment, probably during the reign of Ramesses XI at the end of the 20th dynasty (c. 1099-1069 BC).

The village appears to have been founded at the beginning of the 18th dynasty by king Amenhotep I (c. 1525-1504 BC). From then on the settlement underwent several phases of expansion to the extent that it comprised at least seventy family homes by the time of its eventual abandonment, probably during the reign of Ramesses XI at the end of the 20th dynasty (c. 1099-1069 BC).

Nowadays, the majority of the village houses have been remarkably well preserved. Throughout the settlement, walls still stand to a height of several feet, clearly demonstrating the original living arrangements amongst the densely-packed terraced housing. Even the once-bustling main street remains a prominent feature, dog-legging its way through the centre of the village.

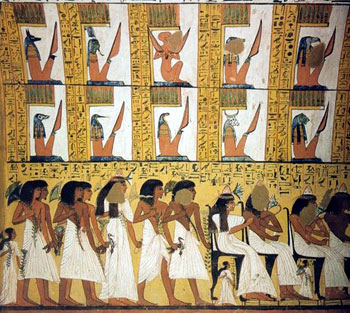

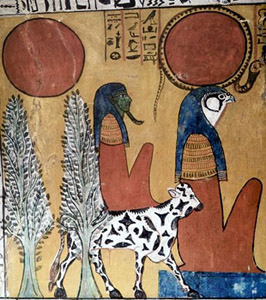

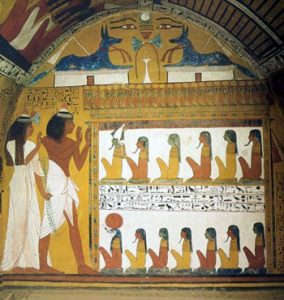

Deir el-Medina is also renowned for the quality of some of the tombs in the local cemetery. The workmen certainly invested heavily in all of the necessary funerary arrangements for their safe transition into the next life. Their tombs were beautifully decorated with religious iconography and especially well-equipped for life in the hereafter.

There is little doubt that the workmen were hugely influenced by the artistic conventions that they employed for their work in the royal tombs. Some can even be seen adopting excerpts from royal funerary texts that would have been so familiar to them. The best preserved tombs date from the first half of the 19th dynasty (c. 1295-1213 BC), a time of great prosperity for the workmen. At the time of writing, three tombs are open to the public, each having been chosen on account of their beautiful frescoes. They belong to two of the workmen, Sennedjem (TT 1) and Pashedu (TT 3), and the chief workman Inherkhau (TT 359). Decorated by skilled artists, these tombs bear a striking comparison to the royal tombs in the neighbouring valleys, hardly surprising given the fact that they were built by the same gang of workmen.

There is little doubt that the workmen were hugely influenced by the artistic conventions that they employed for their work in the royal tombs. Some can even be seen adopting excerpts from royal funerary texts that would have been so familiar to them. The best preserved tombs date from the first half of the 19th dynasty (c. 1295-1213 BC), a time of great prosperity for the workmen. At the time of writing, three tombs are open to the public, each having been chosen on account of their beautiful frescoes. They belong to two of the workmen, Sennedjem (TT 1) and Pashedu (TT 3), and the chief workman Inherkhau (TT 359). Decorated by skilled artists, these tombs bear a striking comparison to the royal tombs in the neighbouring valleys, hardly surprising given the fact that they were built by the same gang of workmen.

For the more adventurous travellers, I would strongly recommend following in the workmen’s footsteps by taking the ancient desert track that leads from the south-west corner of the village, over the mountain ridge and down into their place of work, the Valley of the Kings. It is by no means an easy walk, with the track becoming quite steep and treacherous in places. Simply put, it should only be tackled by the physically fit and those with experience of traversing uneven and tricky terrain. For first timers, it is definitely advisable to seek out the services of one of the local guides, who will gladly offer the service of a donkey for those unaccustomed or unable to make the journey on foot.

Approximately half-way along the mountain pass, at the point where it crests the ridge that separates the royal burial ground from the Nile valley, stand the remains of an ancient group of huts. These spartan buildings were put up by the workmen for their overnight accommodation during the working week in the Valley. It would seem that after a hard day’s back-breaking toil in the royal tomb, the men preferred to retire here for the night, rather than making the longer journey back to their families at Deir el-Medina. High up in in this splendidly isolated and lofty perch, the men would have whiled away their evenings talking about the day’s events at the worksite, singing songs, telling stories or discussing private business matters.

Approximately half-way along the mountain pass, at the point where it crests the ridge that separates the royal burial ground from the Nile valley, stand the remains of an ancient group of huts. These spartan buildings were put up by the workmen for their overnight accommodation during the working week in the Valley. It would seem that after a hard day’s back-breaking toil in the royal tomb, the men preferred to retire here for the night, rather than making the longer journey back to their families at Deir el-Medina. High up in in this splendidly isolated and lofty perch, the men would have whiled away their evenings talking about the day’s events at the worksite, singing songs, telling stories or discussing private business matters.

This is a breathtaking walk, and one that is richly rewarded with spectacular, panoramic views out across the valley cultivation to the mighty River Nile as it serenely charts its perennial course towards the shores of the Mediterranean. Without doubt, this has to be the most uplifting way by which to reach the Valley of the Kings. With plans now afoot to replace tombs such as Tutankhamun’s with full-scale replica models, time is clearly running out for those who have yet to visit these marvels of the ancient world!

One Day tour to Luxor from Cairo by Flight Visiting Best Of Luxor City

If You Go:

Audio guides to the Valley of the Kings, Deir el-Medina and the Tomb of Sennedjem are available at www.iconicguides.com.

About the author:

Dr. Benedict Davies is an Egyptologist, traveller, freelance writer and the founder of MP-3 audio tours “Iconic Guides”. He also holds a PhD in Egyptology from the University of Liverpool and is a leading expert on the community of royal workmen of Deir el-Medina and the Valley of the Kings. A seasoned traveller, Benedict is particularly interested in the culture and art of the ancient Near East and the Far East.

All photos are by Dr. Benedict Davies.