Tamil Nadu, India

by Chandana Banerjee

A grizzled old sculptor, bare-chested and in a blue checked lungi, squats on a low wooden stool working intently on his creation.

“Ganesha’s mouse, Madam,” points out Erudhayam, the guide, who is showing me around Mahablipuram (or Mamallpuram), the historically-rich seaside town near Chennai in Tamil Nadu, on this hot summer morning. The sculptor looks up from his work for a brief moment to acknowledge our presence before going back to his rhythmic scraping, a sound that is part and parcel of the ambience of this quaint seaside town.

“Ganesha’s mouse, Madam,” points out Erudhayam, the guide, who is showing me around Mahablipuram (or Mamallpuram), the historically-rich seaside town near Chennai in Tamil Nadu, on this hot summer morning. The sculptor looks up from his work for a brief moment to acknowledge our presence before going back to his rhythmic scraping, a sound that is part and parcel of the ambience of this quaint seaside town.

The scratch and scrunch of stone, the sonorous ‘tonk tonk’ of hammer and chisel, the high-pitched banshee-like screech of the drill is as much part of Mamallapuram as are the ancient temples and monuments made during the reign of the Pallavas.

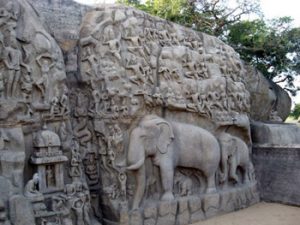

Somewhere in 600-630 A.D., King Mahendravarman laid the foundations of elaborate rock cut cave-temples, and built the Dhramaraja Mandapa for the pilgrims who visited this town. Then from 630 to 688 A.D., his son, Narasimhavarman I, who was called Mahamalla, started the Mahamalla style of temple architecture, which consists of free standing monolithic structures. Most of the monuments at Mamallapuram – the monolithic ratha, sculpted scenes from the Mahabharata and mythology on open rock face of the Arjuna’s Penance, the rock cut cave-temples of Govardhanadhari and Mahishasuramardini, the Jala-Sayana Perumal temple, the sleeping Mahavishnu at the rear part of the Shore temple complex, were built by him. Narasimhavarman I’s son, Rajasimhan ruled from 700 to 728 A.D., and pioneered the masonry-style of architecture and built the magnificent five-storied Shore Temple. There is an old legend here that the king built seven temples, of which, six have been swallowed by the sea and a tsunami.

Somewhere in 600-630 A.D., King Mahendravarman laid the foundations of elaborate rock cut cave-temples, and built the Dhramaraja Mandapa for the pilgrims who visited this town. Then from 630 to 688 A.D., his son, Narasimhavarman I, who was called Mahamalla, started the Mahamalla style of temple architecture, which consists of free standing monolithic structures. Most of the monuments at Mamallapuram – the monolithic ratha, sculpted scenes from the Mahabharata and mythology on open rock face of the Arjuna’s Penance, the rock cut cave-temples of Govardhanadhari and Mahishasuramardini, the Jala-Sayana Perumal temple, the sleeping Mahavishnu at the rear part of the Shore temple complex, were built by him. Narasimhavarman I’s son, Rajasimhan ruled from 700 to 728 A.D., and pioneered the masonry-style of architecture and built the magnificent five-storied Shore Temple. There is an old legend here that the king built seven temples, of which, six have been swallowed by the sea and a tsunami.

If the Shore Temple, the Five Rathas, the Mandapams and Arjuna’s Penance are what this small town is about, then so are the hundreds of sculptors who work in street-side studios, meticulously turning stone, metal and wood into pieces of art. Mamallapuram is all about sculpture, old and new; history and mythology as is the old bespectacled guide in a crisp white veshti (a sort of wrap-around skirt that men wear), who has been standing at the very spot at the gateway of the town for the past 31 years, heralding tourists with his trademark “I can show you Mamallapuram. Want a guide?”

If the Shore Temple, the Five Rathas, the Mandapams and Arjuna’s Penance are what this small town is about, then so are the hundreds of sculptors who work in street-side studios, meticulously turning stone, metal and wood into pieces of art. Mamallapuram is all about sculpture, old and new; history and mythology as is the old bespectacled guide in a crisp white veshti (a sort of wrap-around skirt that men wear), who has been standing at the very spot at the gateway of the town for the past 31 years, heralding tourists with his trademark “I can show you Mamallapuram. Want a guide?”

This guide traverses between the role of the story teller, historian, cultural ambassador, and translator. It is he who introduced me, as he must have done to others, to the soul of Mamallapuram. He had been my guide a month ago, when I first visited the town to admire the ancient monuments. This time, when I tell him that I want to know more about the sculptors – the ancient ones, who disappeared mysteriously, leaving many of their creations, unfinished, and the new sculptors, who carry on the legacy of this temple town, Erudhayam takes me to the Five Ratha road. The showroom with the most opulent sculptures is situated here. It belongs to the award-winning sculptor, Mr. M. Durrai Raj.

At ‘Mayan Handicrafts’, in his sprawling showroom, the entire kingdom of Gods and Goddesses are parked in front of the shop: a languid, life-size Buddha, Saraswati – the serene goddess of learning, the radiant Lakshmi, various sculptures of the laddoo-loving Ganesha, Vishnu and Shiva, favourite deities of South India, Hanuman – the monkey god, and a pair of voluptuous celestial nymphs. Granite elephants and roaring lions find a place among the pantheon of deities. The rooms in the shop are packed with scores of idols, while an equal number jostle for space on the dusty shelves.

Some are exquisite and carved by ‘the master sculptor’; others have been made by apprentices at the studio. Ganesha, the elephant-headed God who is associated with good luck, seems to be a favourite all over Mamallapuram. Here, in Durrai Raj’s shop, I find Ganesha dancing, reading, playing musical instruments, reclining and meditating. Most of the stone sculptures measure about a foot to over seven feet, and are made of various types of stones. Shipped all across the world and to various places in India, the sculptures from this studio are known for their quality and intricate craftsmanship. After spending time at Durrai’s shop, looking at glossy pictures of more statues that peek out from a thick portfolio and admiring the assortment of stone sculptures, I move on, passing other sculpture workshops on the way, where sculptors are hard at work, carving, chiselling, hammering.

Some are exquisite and carved by ‘the master sculptor’; others have been made by apprentices at the studio. Ganesha, the elephant-headed God who is associated with good luck, seems to be a favourite all over Mamallapuram. Here, in Durrai Raj’s shop, I find Ganesha dancing, reading, playing musical instruments, reclining and meditating. Most of the stone sculptures measure about a foot to over seven feet, and are made of various types of stones. Shipped all across the world and to various places in India, the sculptures from this studio are known for their quality and intricate craftsmanship. After spending time at Durrai’s shop, looking at glossy pictures of more statues that peek out from a thick portfolio and admiring the assortment of stone sculptures, I move on, passing other sculpture workshops on the way, where sculptors are hard at work, carving, chiselling, hammering.

I meet another sculptor, Dashnamoorthy, a seasoned artist, who is an alumnus of the Government College of Architecture and Sculpture at Mamallapuram. He has turned the portico of his house into a studio and shop. There he creates medium-sized stone sculptures of gods and goddesses, and sells them to tourists who saunter by. A French couple in cargo shorts and baggy t-shirts walk in to examine the polished, black idols of the pot-bellied Ganesha. They want to take one home, and Dashnamoorthy scurries off to show them some.

Erudhayam the guide, and I cruise through the dusty streets of Mamallapuram, sweat streaming down our faces, in quest of more sculptors and more stories.

Erudhayam the guide, and I cruise through the dusty streets of Mamallapuram, sweat streaming down our faces, in quest of more sculptors and more stories.

All of the workshops along the streets hum with activity. The sound of screeching drills fills the air with their busy cacophony. I peep into a shop where a group of sculptors are immersed in their work. A man in a pair of dirty brown pants and a once-white shirt is chiselling away at a granite sculpture of Shiva, another in faded jeans and a psychedelic shirt works his drilling machine on a slab of stone, willing it to crack and reveal the delicately drawn shape of the idol. In another part of the studio, a man is working on a huge statue of Vishnu, while his friend slaps clay on a model of Buddha. As they work, wrapped up in a thin layer of smoke that swirls up from the kiln, Rajendra, a lecturer at the College of Sculpture and a bronze sculpture specialist, helps a trainee with his metal creation and also gives us a smattering of information on the process of making the metal figures.

“These figurines are made with five metals, which means most have 80% copper, 20% brass, 5% lead, and a little bit of gold and silver,” explains Rajendra, who has been teaching this very subject for the past 20 years.

I am curious to know about the College, which has produced more than half of the town’s sculptors, and wonder what role it has played in re-introducing the art of making sculptures, an art that had disappeared suddenly, after the decline of the powerful dynasty.

Rajendra answers my questions. “The Government started the college in 1957 to promote and revive the art of making sculptures and temples, something that Mamallapuram was known for since ancient times. Over the years, sculpture work has become the chief profession of the people in the town. There’s even a museum here with over 3000 pieces done by the students.”

Most of the sculptors we see around the town are alumni of this college; others learned the art from family members. While nobody here has been able to trace their lineage back to the sculptors of the Pallava Dynasty; the monuments in Mamallapuram and the new age sculptors have a fine bond, and rely on each other to keep the tradition and heritage of this culturally-rich town, alive.

Most of the sculptors we see around the town are alumni of this college; others learned the art from family members. While nobody here has been able to trace their lineage back to the sculptors of the Pallava Dynasty; the monuments in Mamallapuram and the new age sculptors have a fine bond, and rely on each other to keep the tradition and heritage of this culturally-rich town, alive.

“When tourists from India and abroad come to the town to see the monuments, they drop into the studios to buy sculptures. Business is brisk during the tourist season from September to January,” chips in Elumalai, a friend of Rajendra, who is a self-taught sculptor and takes pride in making small idols out of red marble and green stone. While most of the stone sculptures here are large, the marble and green stone deities in Elumalai’s shop near the Vishnu Temple are about eighteen inches tall. Delicately carved by this engineer-entrepreneur-sculptor, these can easily fit into a tourist’s valise or rucksack. “I make sculptures for middle-class people – affordable and portable.” he says.

Elumalai is the only person I’ve met in Mamallapuram, who can speak fluent English. He shows me the way a slab of stone is turned into a breathtaking beauty. “After we select the right size and texture of stone, we draw a rough sketch on it. Then we cut around it with a chisel and a hammer, and smooth the idols with a special set of chisels.”

The sculptor proceeds by drawing the finer details like ornaments, facial features and carves these out with a chisel. The figurines are smoothed further with salt paper in the case of small pieces or with special tools, when it is a bigger sculpture. Sometimes, these are painted black with ink. Electric drills are often used while making larger sculptures.

The sculptor proceeds by drawing the finer details like ornaments, facial features and carves these out with a chisel. The figurines are smoothed further with salt paper in the case of small pieces or with special tools, when it is a bigger sculpture. Sometimes, these are painted black with ink. Electric drills are often used while making larger sculptures.

Row after row, lane after lane, the studios and shops in this seaside town, make and sell sculptures in stone, brass and wood. It is stone that seems to be most popular, while metal is a close runner-up.

As I leave the city, I pass the carved caves and the panels with ancient bass-relief work done by the sculptors of yore, and wonder if there is any similarity in techniques as well as the subjects of the sculptures. Mythology and deities were an important part of the monuments, and so are they in the sculptures that are being made ever since the college was established in Mamallapuram. Stone is still a favoured medium, as it was in the days of the Pallava Kings. While the styles of sculpture work might be different, I can’t help but wonder that both are about etching stories in stone.

If You Go:

Air: The nearest airport, Chennai is 64 km away.

Rail: The nearest rail junction is Chengalpet (30 km). You can also reach Mahabalipuram from Chennai (60 km), Pondicherry (134 km), Trichy (250 km), Madurai (375 km).

Road: You can drive down from Chennai in a hired taxi or hop onto a luxury bus.

The best time to visit this area is in winter, between the months of November and February.

For more information: Government Of Tamilnadu Tourist Office

More Tours of Mahabalipuram

Private Day Tour of Mahabalipuram from Chennai

Full Day Tour to Kanchipuram and UNESCO’s Mahabalipuram with Private Transfer

Excursion to Mahabalipuram from Chennai

About the author:

Chandana Banerjee is an independent writer, journalist and creative writing teacher based in India. She writes for various media like websites, newspapers, magazines, ebooks, e-learning and corporate communications. She also has her own writing company called the Pink Elephant Writing Studio.

Photo credits:

First Mamallapuram, Arjuna’s Penance photo by: Arian Zwegers from Brussels, Belgium / CC BY

All other photos are by Chandana Banerjee.