by Irene Lynxleg

Because of the great distances between communities in rural western Manitoba, our priest couldn’t attend each village for Midnight Mass. I remember when I was 10 years old it was his turn to come to our village.

That evening we got ready and dressed warm with our home made clothes, woolen coats, hats and mittens and brought wool blankets to cover and keep us warm for the sleigh ride to church.

The church with the little white steeple was the tallest building in the community. The steeple pointing to the sky looked like a lonely unicorn sitting on the snow waiting for company.

It was four miles from our farm; too far to walk. My dad and brothers hitched our two plough farm horses to the sleigh and attached bells to the harness. The sleigh had an open box with seats all around except on the front, where a large plank provided a seat for the driver.

Hay was scattered all over the floor of the box to keep our feet warm. It also served as the horse’s food during the service. The horses were brothers called Pat and Jim. They had beautiful black shiny coats and tails with white blazes and looked as though they were wearing tuxedos for a special occasion.

As they trotted pulling the sleigh their breath sent out streams of air like the old locomotives trains. Their tails swung and danced to the rhythm of the swinging bells which could be heard for miles, especially on a cold crisp winter night.

My oldest brother was the driver that night and Mom sat beside him. My Dad did not attend the service. His church was the woods where he would go alone to talk to his Creator.

On the trip we talked, laughed, sang and teased each other to make up for having to be silent during the service. When we arrived we tied up the horses and fed them and brought in our blankets to line the cold church pews. The wooden stove was too small and did not heat the whole church.

When we entered most of the people were already seated. Each family occupied one whole row of the church benches. The parents allowed their children to bring their home-made toys: sling shots, drums, flutes, little dolls dressed in leather and feathers. For snacks we brought dried strips of meat moose, deer, rabbit and bannock packed in empty metal Shamrock lard pails.

The Midnight Mass in my native community was a special Christmas event. The parents socialized after the service and the little children fed Baby Jesus their snacks. During confession time, the grandmas and mothers sang native hymns in the upstairs balcony.

They were called the Crepe Paper Singers because they could not afford to buy lipstick. The women used the red crepe paper that was used for Christmas decorations that was kept hidden behind the old organ in the church. They wet the red paper with their saliva, then applied it to their lips to transfer the deep red dye. I still remember one of the hymns the Crepe Paper Singers sang called ‘Jesus Has Arrived’ (in Saulteaux it’s ‘Aja A Binogee Jesus’). I used to sing it at Christmas for my grandchildren.

After the service we wished everyone a Merry Christmas, climbed into the sleigh for the ride home. As we rode along in silence I noticed it was very light out. I looked up at the sky and saw the evening star Venus, also called the Star of Bethlehem or the Christmas Star.

Opposite the Christmas Star a beautiful golden full Moon glowed. The moonlight lit up the snow-covered ground, and the crusted snow flakes were wearing sparkling diamond tiaras.

When we reached home, before we entered the house we smelt the aroma of cooking. Our father surprised us with a special midnight late dinner. On the table, instead of a turkey was a roasted beaver and from our root cellar he cooked onions, potatoes, carrots and turnips. We thanked the Creator for our wonderful evening and meal and quietly went to bed.

Now every Christmas when I see cards, churches with steeples, horses pulling sleighs and jewelers advertising diamonds, the sparkling snow wearing diamond tiaras, I think of my sleigh ride in the moonlight and my roasted beaver dinner.

If You Go:

Things to do in Winnipeg, Manitoba during Christmas holidays

About the author:

Irene Lynxleg was born on an Indian Reservation 77 years ago in Southern Manitoba (Tootenowazubeng). She was the only child on the reservation to complete Grade 8 but was subsequently sent to a Catholic Residential School. She lived most of her life off the reservation. She has been writing seriously with guidance from the Brock House Society for about 3 years. In 2015, Irene received the Cedric Literary award for First Nation’s writing.

Photo of horse and sleigh byPete Markham from Loretto, USA / CC BY-SA

The best place to start exploring St. Boniface’s heritage is at the former St. Boniface City Hall, which now houses a tourism office. It is also the starting point of a guided walking tour of old St. Boniface. The red brick building dating back to 1906 is the first item on the tour. Other points of interest include an outdoor sculpture garden beside the tourism office, a Romanesque-revival style brick firehouse built in the early 1900s, a cultural center, a train station built in 1913 that now houses a restaurant, a French-speaking university, and St. Boniface Cathedral. The tour ends on the grounds of Saint-Boniface Museum.

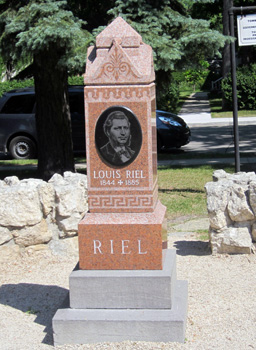

The best place to start exploring St. Boniface’s heritage is at the former St. Boniface City Hall, which now houses a tourism office. It is also the starting point of a guided walking tour of old St. Boniface. The red brick building dating back to 1906 is the first item on the tour. Other points of interest include an outdoor sculpture garden beside the tourism office, a Romanesque-revival style brick firehouse built in the early 1900s, a cultural center, a train station built in 1913 that now houses a restaurant, a French-speaking university, and St. Boniface Cathedral. The tour ends on the grounds of Saint-Boniface Museum. Louis Riel, a controversial figure in Canadian history, was one of Université de Saint-Boniface’s most famed alumni. He is considered a hero by some and a traitor by others. Born in 1844 in St. Boniface, he became a leader of the Métis people, a recognized Canadian aboriginal people of mixed European and First Nations heritage. In the late 1860s unrest grew among the Métis in the Red River area, fearing their livelihood and way of life was threatened by the planned transfer of land from the Hudson’s Bay Company to Canada. In 1869, Riel’s forces took control of Fort Garry, the headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company. From 1869 to 1870, he led a provisional government, a government which would eventually negotiate terms leading to Manitoba becoming a Canadian province and ensuring some protection of French language rights. He is frequently called the “Father of Manitoba”.

Louis Riel, a controversial figure in Canadian history, was one of Université de Saint-Boniface’s most famed alumni. He is considered a hero by some and a traitor by others. Born in 1844 in St. Boniface, he became a leader of the Métis people, a recognized Canadian aboriginal people of mixed European and First Nations heritage. In the late 1860s unrest grew among the Métis in the Red River area, fearing their livelihood and way of life was threatened by the planned transfer of land from the Hudson’s Bay Company to Canada. In 1869, Riel’s forces took control of Fort Garry, the headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company. From 1869 to 1870, he led a provisional government, a government which would eventually negotiate terms leading to Manitoba becoming a Canadian province and ensuring some protection of French language rights. He is frequently called the “Father of Manitoba”. During Riel’s provisional government, his forces arrested men who had plotted to recapture the fort. Thomas Scott, one of the men arrested, was court-martialed and executed by firing squad. The outrage over this incident led the Canadian government to send in forces and regain control of the region. With a bounty on his head, Riel fled to the United States. He returned to Canada, to what is now the province of Saskatchewan, in 1885 to help Métis obtain legal rights. His peaceful petitions produced little result and the Métis rebellion turned violent. Canadian government troops squashed the rebellion. Riel was put on trial for treason. A jury found him guilty but recommended his life be spared. The judge ignored the jury’s recommendation and sentenced Riel to death. He was executed and buried in the cemetery at St. Boniface cathedral. A granite tombstone now identifies his grave, initially marked by a wooden cross.

During Riel’s provisional government, his forces arrested men who had plotted to recapture the fort. Thomas Scott, one of the men arrested, was court-martialed and executed by firing squad. The outrage over this incident led the Canadian government to send in forces and regain control of the region. With a bounty on his head, Riel fled to the United States. He returned to Canada, to what is now the province of Saskatchewan, in 1885 to help Métis obtain legal rights. His peaceful petitions produced little result and the Métis rebellion turned violent. Canadian government troops squashed the rebellion. Riel was put on trial for treason. A jury found him guilty but recommended his life be spared. The judge ignored the jury’s recommendation and sentenced Riel to death. He was executed and buried in the cemetery at St. Boniface cathedral. A granite tombstone now identifies his grave, initially marked by a wooden cross. St. Boniface Cathedral is a major Winnipeg architectural landmark. A fire in 1968 destroyed the 1894 church, leaving its historic stone walls. Behind the facade of the ruined church sits a newer, modern church, a cathedral within a cathedral. Stained glass windows designed by architect Etienne J. Gaboury decorate the new church. Old and new coexist in a quiet and peaceful setting.

St. Boniface Cathedral is a major Winnipeg architectural landmark. A fire in 1968 destroyed the 1894 church, leaving its historic stone walls. Behind the facade of the ruined church sits a newer, modern church, a cathedral within a cathedral. Stained glass windows designed by architect Etienne J. Gaboury decorate the new church. Old and new coexist in a quiet and peaceful setting. Inside the museum, exhibits reveal the lives and culture of Manitoba’s Francophone and Métis communities. The large collection of artifacts in the Louis Riel exhibit include his trunk, a lock of his hair, his shaving kit, his cribbage board, his moccasins, and the coffin he was originally laid in. Louis Riel’s sash, or ceinture fléchée, is also on display. The ceinture fléchée is a traditional piece of French-Canadian clothing, widely worn in the 18th and 19th centuries, wrapped twice and tied around the waist. Other exhibits include depictions of fur trading life, clothing from the 1800s, artwork, and a chapel. My favourite part was the rooms depicting life in days past, complete with weathered wood beams, hooked rugs on wood plank floors, white metal-framed bed, and cast iron stove.

Inside the museum, exhibits reveal the lives and culture of Manitoba’s Francophone and Métis communities. The large collection of artifacts in the Louis Riel exhibit include his trunk, a lock of his hair, his shaving kit, his cribbage board, his moccasins, and the coffin he was originally laid in. Louis Riel’s sash, or ceinture fléchée, is also on display. The ceinture fléchée is a traditional piece of French-Canadian clothing, widely worn in the 18th and 19th centuries, wrapped twice and tied around the waist. Other exhibits include depictions of fur trading life, clothing from the 1800s, artwork, and a chapel. My favourite part was the rooms depicting life in days past, complete with weathered wood beams, hooked rugs on wood plank floors, white metal-framed bed, and cast iron stove. La Maison Gabrielle-Roy, to the east of old St. Boniface, provides glimpses into the life of a middle class Francophone family in the early 1900s and insight into renowned author Gabrielle Roy. Gabrielle Roy was the recipient of many prestigious literary awards and her books, written in French, were translated into many languages. Roy’s father, a colonization officer, had the house built in 1905. Gabrielle Roy was born in 1909, the youngest of 11 children. The house now functions as a museum and rooms have been restored to look as they would have during Gabrielle’s childhood. The floors are original and the wall colours authentic to what would have adorned the Roy household. The furnishings are not the original Roy family furnishings, but are true to the period. The piano in the parlor is a Bell piano, the same kind that had a prominent place in the Roy family’s life.

La Maison Gabrielle-Roy, to the east of old St. Boniface, provides glimpses into the life of a middle class Francophone family in the early 1900s and insight into renowned author Gabrielle Roy. Gabrielle Roy was the recipient of many prestigious literary awards and her books, written in French, were translated into many languages. Roy’s father, a colonization officer, had the house built in 1905. Gabrielle Roy was born in 1909, the youngest of 11 children. The house now functions as a museum and rooms have been restored to look as they would have during Gabrielle’s childhood. The floors are original and the wall colours authentic to what would have adorned the Roy household. The furnishings are not the original Roy family furnishings, but are true to the period. The piano in the parlor is a Bell piano, the same kind that had a prominent place in the Roy family’s life. Fort Gibraltar is a replica of the original fur trading post built in 1809. The fort was abandoned in 1835 and destroyed by flood in 1852. The replica was built in 1978 to reflect key elements of life in the Red River valley from 1815 – 1821. Inside its wooden walls, costumed interpreters relive daily life of the original inhabitants. They are behind the counter in the general store, forging metal at the blacksmith’s shop, sewing, tending to an outdoor fire, and working in the workshop. Fur pelts hang in the warehouse. A fur press sits along one wall. It was used to press the fur into 90 pound bales for transport in canoe. A voyageur would typically transport two bales at a time.

Fort Gibraltar is a replica of the original fur trading post built in 1809. The fort was abandoned in 1835 and destroyed by flood in 1852. The replica was built in 1978 to reflect key elements of life in the Red River valley from 1815 – 1821. Inside its wooden walls, costumed interpreters relive daily life of the original inhabitants. They are behind the counter in the general store, forging metal at the blacksmith’s shop, sewing, tending to an outdoor fire, and working in the workshop. Fur pelts hang in the warehouse. A fur press sits along one wall. It was used to press the fur into 90 pound bales for transport in canoe. A voyageur would typically transport two bales at a time.