by Roy A. Barnes

“The Tide,” is Norfolk’s light rail system and I found it useful to help me get to some off-the-beaten-path sites that were related to the years before, during, and after the Civil War. The downtown area is easily navigable by foot, so I was able to explore more historical gems related to America’s great conflict with my comfortable walking shoes.

I headed northwest of downtown in search of an out of the way former military installation called Fort Norfolk, where wartime activities had taken place beginning with the American Revolution. It’s just three blocks from the light rail system’s EVMC/Fort Norfolk Station and inside the grounds of the US Army Corp of Engineers (behind a multi-story retirement home).

Fort Norfolk goes back to the Revolutionary War era. It was abandoned by the Rebels in 1862, but not before supplying the ammo used by the Confederates’ CSS Merrimac against the USS Monitor in the great ironclad battle. The Union Army made it a prison and then the fort served as a naval installation until 1878. Brick buildings have been painted white and are surrounded by high grassy mounds, allowing some great views of the Elizabeth River and dockyards. In the midst of a sunny, breezy day, I could feel the presence of those past centuries long gone.

The light rail system’s Harbor Park Station leads right up to the Norfolk Tides’ baseball park, where minor leaguers strive to make it to the big leagues each season. But just behind the left field parking lot, a more important game was played out. These were areas where slaves strived to make it to freedom via some Virginia Underground Railroad sites of 150-plus years ago. Conspicuous yet unmarked pathways lead to these unkempt areas where once Higgins Wharf and Wright’s Wharf stood, overlooking the Elizabeth River. Now only fisherman can be found.

The light rail system’s Harbor Park Station leads right up to the Norfolk Tides’ baseball park, where minor leaguers strive to make it to the big leagues each season. But just behind the left field parking lot, a more important game was played out. These were areas where slaves strived to make it to freedom via some Virginia Underground Railroad sites of 150-plus years ago. Conspicuous yet unmarked pathways lead to these unkempt areas where once Higgins Wharf and Wright’s Wharf stood, overlooking the Elizabeth River. Now only fisherman can be found.

Slaves who could navigate this isolated area would be able to secretly board ships sailing for the north, like the Augusta, which charged legal passengers some $7 dollars for passage to New York (meals included) in the mid-nineteenth century, departing Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays at 6:30 a.m. I found myself feeling isolated while pondering how challenging it would be to risk one’s life to get freedom, avoiding the pitfalls of ship raids for fugitive slaves. The common knowledge around town, through Abolitionist newspapers, told about the city’s role in helping escaped slaves.

Just a few blocks from “The Tide’s” Monticello Station, the Norfolk History Museum at the Willoughby-Baylor House can be found. Built in 1794, it has free entrance. The city’s history is extensively covered through pictures, maps, and aged artifacts including the occupation history of Union forces from 1862-1865. I learned about how whites evaded being drafted by getting African Americans to substitute for them in “Negro substitute” centers, some located in Norfolk. I discovered the violent aftermath when race riots were common after the war’s end, as blacks were striving to assert their new freedoms due to the 1866 Civil Rights Act. While ascending the second floor, I noticed some gripping black and white photos of Norfolk’s people and places during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Just a few blocks from “The Tide’s” Monticello Station, the Norfolk History Museum at the Willoughby-Baylor House can be found. Built in 1794, it has free entrance. The city’s history is extensively covered through pictures, maps, and aged artifacts including the occupation history of Union forces from 1862-1865. I learned about how whites evaded being drafted by getting African Americans to substitute for them in “Negro substitute” centers, some located in Norfolk. I discovered the violent aftermath when race riots were common after the war’s end, as blacks were striving to assert their new freedoms due to the 1866 Civil Rights Act. While ascending the second floor, I noticed some gripping black and white photos of Norfolk’s people and places during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

On a beautiful Saturday morning I took a 90 minute Norfolk Walkabouts tour. I sauntered through the Freemason neighborhood, near to the shipyards and docks, just to the northwest of downtown, down cobblestone lanes lined with sycamore and oak trees, dominated by homes where ship’s captains once lived.

Their stately dwellings display many chronological styles of architecture including Federal, Queen Anne, Georgian Revival, etc. At the corner of Botetcourt St. and Freemason St. (the first street in Norfolk with gas lamps), the union used Dr. William B. Seldon’s home as their headquarters. Seldon was the Surgeon General for the Confederates, and would host Confederate General Robert E. Lee after the great conflict in 1870.

For those who are into self-guided tours, I found the Cannonball Trail suitable for helping get more intimate with Norfolk. The walk takes explorers to potentially 43 different stately homes and other structures (dating from the 1790s until the early 1900s) around Norfolk’s waterfront, downtown, and Ghent neighborhood, offering views of such Civil War sites like the U.S. Customhouse, used as a dungeon by the Union Army.

For those who are into self-guided tours, I found the Cannonball Trail suitable for helping get more intimate with Norfolk. The walk takes explorers to potentially 43 different stately homes and other structures (dating from the 1790s until the early 1900s) around Norfolk’s waterfront, downtown, and Ghent neighborhood, offering views of such Civil War sites like the U.S. Customhouse, used as a dungeon by the Union Army.

One of the stops is St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, which existed when it was the American colonists versus King George III. It served as a Union Army chapel during the War Between the States. The house of worship received $3,600 in damages following the war from Uncle Sam for damages sustained during the occupation, but got no money from the British for shooting a cannonball into one of its exterior walls on January 1, 1776, which can be seen today.

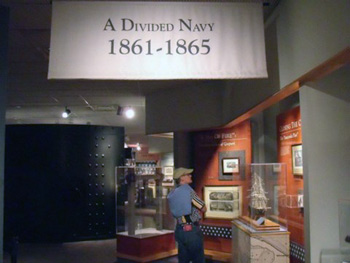

I got more insight into the maritime aspects of the Civil War when I visited the massive three-story high Nauticus complex on the city’s waterfront. It’s an easy walk from lower downtown. Inside Nauticus on the second floor is the Hampton Roads Naval Museum, where naval battles between the North and South get a lot of attention.

I learned through those particular exhibits that African Americans actually made up 16 percent of the Union’s North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. I also didn’t know that Union General George McClellan attempted to cut off the rail hubs and water routes like an anaconda snake (i.e., “Anaconda Plan”) would use on its prey. This ultimately led to the eventually abandonment of the city by the Confederates.

I learned through those particular exhibits that African Americans actually made up 16 percent of the Union’s North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. I also didn’t know that Union General George McClellan attempted to cut off the rail hubs and water routes like an anaconda snake (i.e., “Anaconda Plan”) would use on its prey. This ultimately led to the eventually abandonment of the city by the Confederates.

Besides Civil War exhibits, large exhibits cover many aspects of the Norfolk area’s naval history during America’s wars plus ocean and weather science through hands on displays (and actual hands-on feels of sea life like Horseshoe crab). Videos, scale models, and artifacts abound here. One can attempt to maneuver a manned underwater vehicle simulator or play a video game where getting at some treasure in the ocean is the objective. The exhibits are nicely-spaced to where I had some elbow room to ponder what I read and saw, even though the place was crowded with civilians and former Navy personnel who serve or served this country at sea.

It’s not hard to miss the Nauticus complex, for next to the super-sized building is the Battleship Wisconsin, which is 887 feet, 3 inches long from the bow to the stern, almost the length of three football fields. Guests are allowed to roam the ship’s deck, including some of the upper levels, and can get a close view of the massive firepower the Wisconsin once used.

If You Go:

♦ Norfolk Tide Light Rail: www.gohrt.com/services/the-tide

♦ Fort Norfolk: www.virginia.org/Listings/HistoricSites/FortNorfolk

♦ Willoughby-Baylor House: www.chrysler.org/about-the-museum

♦ Norfolk Walkabouts tour: www.facebook.com/NorfolkWalkabouts

♦ Cannonball Trail/Underground Railroad brochure: issuu.com/dia1/docs

♦ Nauticus: www.nauticus.org

♦ Norfolk Tourist Information: www.visitnorfolktoday.com

About the author:

Roy A. Barnes attended a press trip sponsored by Visit Norfolk, but what he wrote is his impressions without any vetting by the sponsor. He’s a frequent contributor to Travel thru History, and writes from southeastern Wyoming.

All photos are copyright Roy A. Barnes, and may not be used without permission:

Fort Norfolk

Higgins Wharf Underground Railroad

Union Commanders’ House

St. Paul’s Church

Nauticus complex