A Tribute to My Family’s Heritage

by W. Ruth Kozak

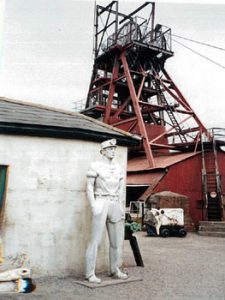

Big Pit Mine, Wales

Kitted out in a helmet, cap lamp, battery pack and a miner’s belt, I enter the pit-cage and descend 90 meters to a world of shafts, coal faces and underground roadways. Guided by a good-natured ex-miner guide, I am about to experience a real sense of life in the coal pit.

Kitted out in a helmet, cap lamp, battery pack and a miner’s belt, I enter the pit-cage and descend 90 meters to a world of shafts, coal faces and underground roadways. Guided by a good-natured ex-miner guide, I am about to experience a real sense of life in the coal pit.

My pit-lamp lights the inky darkness. Along the floor, tracks still remain for the coal trams. I follow the guide through the low-ceilinged, dank tunnels and arrive at one of the air doors. The miner guide instructs everyone to turn off their lamps. I hold my hand in front of my face and can not see it. Now I know the meaning of “pitch-black” darkness.

“That’s what it was like when the lamps blew out,” the guide says. “But of course, the real problem was the rats!”

I am inside the Big Pit Mine, which until its closure in 1980 was the oldest working mine in South Wales. Sunk in 1860, Big Pit forms part of the Blaenafon mine which is now classified as a heritage site and one of the Mining Museums of Wales. The pit’s shaft extends to a depth of 90 meters and at its peak in 1913 employed 1300 men. By 1966 it was the only deep mine left in that area. In 1980 the workforce had declined to 250 and the mine was closed. It reopened in 1983 as a visitor’s centre.

The Welsh Coalfields

As far back as I have traced my Welsh family’s genealogy, most of the men were coal miners. My great-grandfather, and even my great-grandmother, worked in the mines from the age of eight. My father worked in the mines from the age of 14. As a child, I grew up listening to Dad’s mining stories. So on a recent trip to Britain, I decided to visit some of the sites that were part of my family’s heritage.

As far back as I have traced my Welsh family’s genealogy, most of the men were coal miners. My great-grandfather, and even my great-grandmother, worked in the mines from the age of eight. My father worked in the mines from the age of 14. As a child, I grew up listening to Dad’s mining stories. So on a recent trip to Britain, I decided to visit some of the sites that were part of my family’s heritage.

There were two coal fields in Wales: The South Wales Coalfield, which extended nearly 90 miles from Pontypool in the East to St Bride’s Bay in the West, and the North Wales coalfield which extended from the Point of Ayr south-eastward to Hawarden and Broughton near Chester.

I began by visiting the Big Pit National Mining Museum at Blaenafon. Big Pit located at the head of the Afon Llwyd Valley in the North Gwent uplands, stands on a hillside overlooking the town on the bracken-clad moors. The entire area is covered by early coal opencasts. Iron ore and limestone as well as coal outcrops were found here dating back to medieval times. The opening of the Blaenafon Ironworks in 1789 created an ongoing requirement for coal.

Blaenafon

The town of Blaenafon, founded in the 1700’s, is one of the best surviving examples of a Welsh industrial community, and still retains many characteristic features from the 19th century such as terraced housing, shops, chapels, and a Workman’s Hall. On the hillside near the town, Big Pit stands on the site of an earlier mine, Kearsley Pit. The original 40- metre shaft, sunk in 1860 was extended to a depth of 90 meters. The colliery produced more than 100,000 tonnes of coal from an area of about twelve square miles, from nine different coal seams.

The town of Blaenafon, founded in the 1700’s, is one of the best surviving examples of a Welsh industrial community, and still retains many characteristic features from the 19th century such as terraced housing, shops, chapels, and a Workman’s Hall. On the hillside near the town, Big Pit stands on the site of an earlier mine, Kearsley Pit. The original 40- metre shaft, sunk in 1860 was extended to a depth of 90 meters. The colliery produced more than 100,000 tonnes of coal from an area of about twelve square miles, from nine different coal seams.

Like all mines in South Wales, coal was cut by hand and the mine employed both men and women. Until the child-labour laws came into affect at the turn of the 20th century, even children as young as four worked in the pits. In 1908 a mechanical conveyor was installed at Big Pit and it was the first one electrified. The winding gear was driven by a steam engine until 1953 when a mechanical cutter and loader pulled it along by a chain.

The hour-long tour of Big Pit Mine takes you down in the pit cage into the underground roadways, through air doors, to explore traditional and modern mining methods. On the surface you can explore the colliery buildings: the winding engine-house, blacksmith’s workshop and pithead baths.

Exploring those black tunnels brought the lives of my father and my great-grandfather into a clearer perspective. In the old days, the miners worked sixteen-hour days, six days a week. As the miner-guide talks about the mines, both in the past and present times, I recall my father telling me how he would walk to the Bedwas Navigational Mine, five kilometers from his village, Caerphilly, to the pit face in the pre-dawn darkness to emerge hours later in the night. The miners always sang as they walked to and from the collieries, their tenor voices rising in the sweet Welsh treble, songs of their labours, and joyful songs celebrating another day of life. It helped keep their spirits up.

Down in the bowels of Big Pit, as I stand in the impenetrable darkness, my lamp extinguished, the guide explains how the children working as trappers, opened and shut the air doors when the coal trams came down the tracks.

“There were always rats, running along the walls and floor, over the children’s feet,” he says. “ If their lamps went out, they would have to remain there all day in the pitch darkness. It was impossible to relight the lamps once they were extinguished, so they stayed there all day in the dark tunnel, attached to the air door by a cord.”

Children and women were employed to load the trams and clean the pit pony’s stables.It was necessary to keep the stables clean as manure formed the deadly methane gases that caused explosion. The pit ponies lived in the mines for fifty weeks of the year, until there was a Miner’s Holiday, when they would be taken to the surface blindfolded against the glare of the sun. The miners also used caged canaries to detect gas in the tunnels. So long as the canaries sang they knew the air was clean and safe.

Senghenydd Mining Disaster

Unlike other collieries in Wales, Big Pit Mine has the reputation of never having had an explosion or serious accident. No Welsh mining community has ever suffered such a terrible loss as the village of  , the home of my great-grandfather. The first disaster was on Friday, May 24, 1901. Between the end of the night shift and beginning of the day shift, just as the last cage full of night shift workers were disembarking at the surface, the men heard a rumble and dashed for the safety of the lamp room. Two quick explosions in succession followed. A column of dust and smoke shrouded the pit accompanied by the sound of splintering woodwork and tearing metal. A third explosion rocked the village. 83 men, including my great-grandfather and two other family members were below ground preparing for the day shift when the disaster occurred. Only one man was brought out alive. William Harris, an ostler, was found alive but severely burned lying by the side of his dead horse.

, the home of my great-grandfather. The first disaster was on Friday, May 24, 1901. Between the end of the night shift and beginning of the day shift, just as the last cage full of night shift workers were disembarking at the surface, the men heard a rumble and dashed for the safety of the lamp room. Two quick explosions in succession followed. A column of dust and smoke shrouded the pit accompanied by the sound of splintering woodwork and tearing metal. A third explosion rocked the village. 83 men, including my great-grandfather and two other family members were below ground preparing for the day shift when the disaster occurred. Only one man was brought out alive. William Harris, an ostler, was found alive but severely burned lying by the side of his dead horse.

The Universal Steam Coal Company, one of the deepest mines in the coalfield, had a reputation for being a hot, dry, dusty, gassy mine that produced some of the best steam coal. Many enquiries were made after the 1901 explosion, and recommendations were made but not put into place. Unfortunately, this became the precursor to a much great disaster twelve years later.

On Tuesday, Oct. 14, 1913, after the day shift had been down in the pit for two hours, a massive explosion ripped through the mine, wrecking the pithead gear, shooting the cage into the air. Fires raged underground, fed by the workings of the fans. Fallen roof beams cut off air supplies. Some men who were trapped on the east side were rescued. The rest were not so fortunate. 436 miners were killed in the blast. Only 72 bodies were recovered. No other mining community in Wales had ever suffered such a loss. Every street in the village mourned the death of a relative. One woman lost her husband, three brothers and four sons.

The Universal Mining Company was held responsible for the deaths, but after a long legal battle the site manager and company directors were fined a mere 12 Pounds between them — less than six pence for each death. What a price to pay for coal! The mine was closed in 1928. One survivor said: “There was more fuss if a horse was killed underground than if a man was killed. Men came cheap. They had to buy horses.”

Senghenydd, located in the Aber Valley, south of Blaenafon, was just a small mining village at the time of the explosions, and it has not grown much since the Universal colliery closed. I had no trouble finding information about the mine where my great-grandfather had died. A friendly shopkeeper directed me to a tiny community centre, which had once been the miner’s social club. On the walls are photos of the disaster and the retired miner at the Centre was happy to provide details.

I found my great-grandfather’s name listed in the memorial book of the Universal disasters, among the others killed. George Filer, age 73, the oldest man to die in the pit that fateful day. Great-grandfather’s address is also listed in the memorial book, and amazingly I was able to find his house on the High Street. Nearby is the memorial for the miners killed in the two disasters, a reconstruction of the winding gear used at the Universal Collieries.

Bedwas Navigational Colliers, Caerphilly Wales

My father, Fred Filer, was born in Caerphilly a year after his grandfather died. Caerphilly, was then a small mining village employing men in the nearby Bedwas Navigational Collieries. This mine, which produced both steam and house coal, was at its peak output in 1913, but after several bitter industrial struggles the colliery closed. My father began working in Bedwas Colliery when he was fourteen. By 1928 the miners, refusing to take wage cuts, forced the mine to close for two months. It reopened with scab workers and the South Wales Miners Federation, which had sought better wages and improved working conditions in the mine, was banned. There were further conflicts in the early 1930’s including riots. My father, a union activist, as well as many other miners involved had their mining cards confiscated during the dispute. Later the Mining Federation was reinstated. My father immigrated to Canada after losing his mining card, and became a Baptist minister. He was sent as a circuit preacher to Estevan, Saskatchewan to work alongside his friend, a young Scottish-born Baptist minister and future Premier Tommy Douglas, to help the troubled mining communities of southern Saskatchewan.

My father, Fred Filer, was born in Caerphilly a year after his grandfather died. Caerphilly, was then a small mining village employing men in the nearby Bedwas Navigational Collieries. This mine, which produced both steam and house coal, was at its peak output in 1913, but after several bitter industrial struggles the colliery closed. My father began working in Bedwas Colliery when he was fourteen. By 1928 the miners, refusing to take wage cuts, forced the mine to close for two months. It reopened with scab workers and the South Wales Miners Federation, which had sought better wages and improved working conditions in the mine, was banned. There were further conflicts in the early 1930’s including riots. My father, a union activist, as well as many other miners involved had their mining cards confiscated during the dispute. Later the Mining Federation was reinstated. My father immigrated to Canada after losing his mining card, and became a Baptist minister. He was sent as a circuit preacher to Estevan, Saskatchewan to work alongside his friend, a young Scottish-born Baptist minister and future Premier Tommy Douglas, to help the troubled mining communities of southern Saskatchewan.

Nothing is left of the coal pits at Bedwas. The colliery closed, along with others in South Wales, during the miner’s strike of 1984/85 and was never reopened due to damage of two coalfaces during the strike. When I first visited it several years ago, there were still ruined buildings at the pit site. Now the slagheaps, long overgrown with grass, have sprouted new housing developments.

Nothing is left of the coal pits at Bedwas. The colliery closed, along with others in South Wales, during the miner’s strike of 1984/85 and was never reopened due to damage of two coalfaces during the strike. When I first visited it several years ago, there were still ruined buildings at the pit site. Now the slagheaps, long overgrown with grass, have sprouted new housing developments.

Caerphilly, most noted for it’s well-restored Norman castle, still boasts many of the original buildings of my father’s time, including the school he attended, the mining chapels where he often spoke. The family home on Windsor Street is now converted to a law office. In the cemetery of St. Martin’s Church are many graves of those killed in the Senghenydd explosion: fathers and sons, brothers and uncles. Ironically, one of my cousins lives in what was once the posh district of Caerphilly, in a newly renovated mansion formerly belonging to one of the mining bosses.

Mining, once Wales’ former major industry is now almost extinct. Only one deep mine is still working: the Tower Colliery, at Hirwaun, Glamorgan, operated by the Miner’s Co-operative since 1984. There are other small mines still in existence including Blaenant drift mine, which is located next to the Cefn Coed Colliery Museum at Neath, near Swansea.

If You Go:

INFORMATION ABOUT THE BIG PIT MINE:

Big Pit National Mining Museum,

Blaenafon, Torfaen NP4PXP

Open 7 days a week, March – November, 9.30 – 5 pm

For winter times, please telephone.

No charge for entry.

Visitors must be 5 years of age or at least 1 metre tall to go underground.

Wear warm clothing and suitable footwear.

No electrical devices, flash cameras or lighters are allowed in the underground

Tel: 01495-790311 – Fax: 01395- 792618

Movie tour of Big Pit Mine

MORE INFORMATION ABOUT MINES AND MINING MUSEUMS

www.theheritagetrail.co.uk/industrial

RHONDDA HERITAGE PARK (Lewis Methyr Colliery)

www.netwales.co.uk/rhondda-heritage

WELSH SLATE MUSEUM

www.nmgw.ac.uk/wsm

BEDWAS NAVIGATIONAL COLLIERY

www.users.waitrose.com

TOWER COLLIERY

www.minersadvice.co.uk/tower.htm

SENGHENYDD UNIVERSAL COLLIERY

www.welshcoalminers.co.uk/GlamEast/Senghenydd.htm

CEFN COED COLLIERY MUSEUM

www.aboutbritain.com/CefnCoedCollieryMuseum.htm

SOUTH WALES MINING MUSEUM, near Port Talbot

www.neath-porttalbot.gov.uk/tourism/heritage

About the author:

W. Ruth Kozak grew up hearing her father’s mining stories so the opportunity to actually experience what it was like down in the coal pits was a remarkable adventure. Ruth recently toured the Britannia Mine Museum and mine site near Squamish B.C. once the largest copper mine in the British Empire. The recent rescue of the Chilean miners from their 68 days of entrapment were are reminder of the dangerous lives her family members once lived.

Photo credits:

First Blaenavon Big Pit photo by: Steinsky / CC BY-SA

All other photographs by W. Ruth Kozak.