North-East England

by Marc Latham

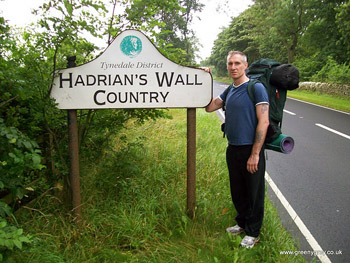

Hiking Hadrian’s Wall in August

Painted Picts once roamed northern lands where

Cheviot cerulean mountains smoulder in the distance;

framing green and yellow.

Green fields of pasturing animals mixed

with barley, rapeseed and wheat providing the yellow.

Swallows and curlews, shearing and harvesting

Grottingham Cottages and Keepwick Fell

thistles and poppies

Hadrian’s Wall stretching from coast to coast

poppies and thistles

Hangman’s Hill and Written Crag

harvesting and shearing, hawks and housemartins

above golden fields of wheat, rapeseed and barley

sheep and cattle graze emerald meadows

stretching corn and lime

to sharp edged blue horizon Pennine peaks;

where wild Brigante spirits still ride free

After a day of walking westwards with very little evidence of any Roman walls ‘the Eel’ Eley, I returned to the Hadrian’s Wall path for a big day of sightseeing at a battle site marked on the map. However, upon arrival we found out it was Heavenfield, and the information at the entrance to the grounds of St. Oswald’s church said it was the site of an important Dark Ages battle between British kingdoms in AD 635: 200 years after the Romans departed British shores!

St. Oswald and the Battle of Heavenfield

It was as if we’d arrived in the wrong time period, as fictional time travellers often seem to do, and had by-passed Roman occupied Britain altogether. There was no mention of Hadrian, or even a Caesar; instead we learnt that Heavenfield was where King Oswald of Northumbria defeated Cadwallon of Gwynedd’s army to restore the Kingdom of Northumbria to its dominant position in 7th century ‘Dark Ages’ Britain. Hadrian’s Wall was still standing at the time, and could have been the arranged meeting point.

Oswald was said to have had a holy vision on the eve of the Heavenfield battle, and he ordered his men to erect a big cross where they camped. There is a large wooden cross at the entrance to St. Oswald’s church to represent this, and despite his later defeat to the pagan Mercians there are other churches dedicated to St. Oswald across the world. A friendly local woman told us that the dead from the battle were buried in a field across the road, and that the pasture is now protected from deep digging out of respect.

St. Oswald’s Way

The information board also had a map showing the route of St. Oswald’s Way (97 miles, 156 kilometers), which stretches from the church to the north-east coast locations associated with St. Oswald. We had largely covered that route over the previous few days with our hosts, Paul and Laura: taking in the medieval castle of Warkworth near Amble, and the picturesque coastal villages of Alnwick and Seahouses. Further up the coast we marveled at Bamburgh, which has a history every bit as intriguing as the castle is majestic. It was chosen as the home of the Anglo-Saxon royalty ruling Northumbria in the seventh century.

King Aethelfrith, Oswald’s father, was known for his ferocity, and after he died Oswald and his siblings fled for their own protection to the monastery on the Inner Hebrides island of Iona in western Scotland, where they were converted to Christianity. Oswald returned to Bamburgh when he was strong enough, and after winning back the crown he sent for a bishop from Iona to help him convert the pagan Northumbrians. When Saint Aidan arrived they set up the monastery of Lindisfarne on a nearby island in 635.

The Holy Island of Lindisfarne is still well worth a visit. A priory resident on the island since the 7th century and a 16th century castle provide stimulating landmarks as well as great views of the Farne Islands farther out at sea and the mainland to the south. On a clear day the volcanic rock that supports the castle provides an ideal promontory for relaxing and dozing under the sun to absorb the harmonious mixture of rich island history and fresh sea air. The mystique of the island is maintained by its natural seclusion: the causeway that links the island to the mainland is submerged by sea twice a day when the tide is in. It is wise to check safe times to travel on the causeway with the tourist board before making the journey.

The north-east castles and monasteries later drew interest from Viking and Norman invaders, as well as being strategically important locations in the wars between English and Scottish royalty.

Hadrian’s Wall: From Heavenfied to the Temple of Light

“Having completely transformed the soldiers, in royal fashion, he made for Britain, where he set right many things and – the first to do so – drew a wall along a length of eighty miles to separate barbarians and Romans.” (The Augustan History, Hadrian 11.1)

After leaving Heavenfield we headed west on the Hadrian’s Wall path. We passed colourful views to the north and south which inspired the introductory poem before reaching the first length of actual wall at Planetrees. The broad foundations and narrower upper wall at the site are evidence of how the Romans had initially planned a ten feet (about three metres) thick wall but had then cut it back to six or seven feet (two metres) for two-thirds of the wall.

The Roman-Britain website explains that the ‘Wall faced front and rear with carefully cut stones set in mortar and an infill of rubble and lime cement or puddled clay. The front face of the wall sported a crenulated parapet, behind which the soldiers patrolled the wall along a paved rampart-walk.’

There were also ditches on either side of the wall, with those in the south known as vallums, and the path now follows them for much of the route. Milecastles, turrets and forts provided regular trusses to keep the wall strong and well-defended, and they now provide the historical highlights on the walk.

The wall was conceived by Emperor Hadrian after his visit to Britain in AD 122. It was built both to keep the Picts from what is now Scotland out of the Roman Empire and to divide the Picts from the Brigantes; a tribe dominant in northern England that did not accept Roman occupation and that had struck up an alliance with the Picts that worried the Romans.

Continuing west the next highlight was Chesters; near the village of Chollerford. It is the best preserved Roman cavalry fort in Britain. There are extensive foundations on view here, as well as the structure of a commandant’s house and the multi-roomed military bath-house. A museum houses Roman artifacts found in archaeological digs on the site.

The Chesters fort was constructed to guard the bridge across the River North Tyne, and is thought to have been built early in the third century. There are still substantial remains of an abutment and piers on the other side of the river, and it is free to access that site.

It was now mid-afternoon, so we decided to make the Procolitia fort the final destination on our westward Hadrian’s Wall hike, as we also had to walk back to the campsite near Acomb; across the valley from Hexham. Three miles later we arrived at Procolitia to find that it is now a car park! However, the extra miles were not in vain, as behind the car park there is the mithraeum: a temple to Mithras, the Persian sun god that the Romans imported into Britain.

Procolitia, also known as Brocolitia, was discovered in 1949, and excavations in the following year found that its boggy location had done a good preservation job. There is still detail in a statue of a deity with three holes bored behind the god’s head. A candle was lit behind the stone during ceremonies and light would shine through. Third century inscriptions to the invincible god of Mithras are also still clearly visible.

It was good to reach the day’s highlight (no pun intended) at the end of the westward walk, and also fitting to have visited the god of light on a gloriously sunny day. Moreover, after stopping off for food and ale in the Hadrian pub beer garden on the edge of the village of Wall on the return journey, iridescent lights appeared in clouds before a stunning sunset took over the horizon.

Although its worshipers are long gone maybe they were right about Mithras being invincible.

Alnwick Castle and Lindisfarne Day Trip from Edinburgh

If You Go:

Newcastle is the main entry point to the region: it has air, ferry, road and rail links with many destinations in the UK and overseas. For more information see Newcastle Gateshead.

Trains run from Newcastle to Alnwick and buses to Bamburgh

Hadrian’s Wall starts in the east from Wallsend in Newcastle.

Entrance to substantial Hadrian’s Wall sites, such as Chesters, cost £4.50.

Useful Websites

Visit Northumberland

The Holy Isle of Lindisfarne

Hadrian’s Wall Northumberland

Roman Britain

About the author:

Marc Latham traveled to all the populated continents during his twenties, and studied during his thirties, including a BA in History. He now lives in Leeds, and is trying to become a full-time writer. A collage of photos from this walk have been made into a video that is viewable on: www.youtube.com/user/greenygrey3

All photos are by Marc Latham.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.