by Georges Fery

The collapse of so many Maya kingdoms toward the end of the eighth century raises questions that, to this day, are still hotly debated among scholars. We will chiefly focus here on the great Maya cities of Calakmul, Tikal and Teotihuacán on the central plateau of Mexico. Calakmul was an important kingdom that, like Tikal, survived the demise of older Preclassic cities (1000 BC/250 AD), and prospered in the Early Classic (250-550); unless otherwise noted, all dates are AD/CE). Calakmul was an important Terminal Classic kingdom that, like Tikal, survived the demise of other cities and prospered in the Early Classic (220-550). Its earliest origin, however, remains stubbornly uncertain for its association with its first settlement at Dzibanché, where groups of people migrated from the south in today’s Guatemala. As Martin and Grube point out, we have a lengthy list that traces the city’s royal line back to a “founder,” but in many ways this document poses more questions than it answers (2000:116-137). Of note is the no less puzzling ceramics codex-style record, for the ceramics were not produced at Calakmul but in the old heartland of the Late Preclassic (400 BC/100 AD), in the El Mirador Basin around the ancient city of Nakbè in today’s Guatemala. At its peak during the Classic period, the territory was under direct control of the k’uhul kaanu’l ajaw (the royal title of Holy Lord of the Ka’an kingdom), as the kings of the Calakmul polity were known. The kingdom controled over five thousand square miles in today’s State of Campeche, Mexico, about twenty-four miles north of the ruins of El Mirador. It was at least as large in area and population as any other Late Classic kingoms (550/830) in the central Maya lowlands, including Tikal (Folan, 1988; Fletcher, Gann, 1992,).

The kingdom’s extensive presence and influence in southern Yucatán is marked by the distribution of a glyph of the snake head sign, that reads “Ka’an” meaning snake in Maya. Calakmul is referred as the “Snake Kingdom” by scholars, although some argue that the emblem glyph may not refer to a snake at all but to a bat. The debate still goes on, because it stems from the snake’s ability to shed its skin as it grew (molting), the ancient mind understood as its rebirth. Furthermore, the snake symbol depicted the life-giving rain, which in both Teotihuacán and Maya religion was associated with Tlaloc, the Nahuatl god of rain. According to Cyrus Lundell, who named the site, the word calakmul in Maya translates as ca-two, lak-adjacent, and mul-mound, meaning, the “City of Twin Pyramids.” Calakmul was built in a concentric fashion and can be divided into zones as one moves outward from the core of the site, that covers 7.7 square miles/sm2.

The city’s late classic population density was estimated at 2564 residents per square mile (sm2) in the site core of 47/sm2, and 1076/sm2 in the periphery. It was built on a rise of about 115 feet overlooking a seasonal marshland to the west, an area of twenty-one by five miles, that provided an important year-round source of water. The site core of inner Calakmul, was known as Ox Te’ Tuun, which translates as “Three Stones” (Shele, Freidel, 1990, Martin, Grube, 2000), a reference to the mythological three stones of creation from the beginning of time in the Maya religion. In the eight square miles area beyond, 6,250 structures were mapped, the largest of which is the Great Pyramid, or Structure.2 which is over 148 feet high making it one of the tallest of the Maya pyramids. The city was built in a concentric fashion and can be divided into zones as one moves outward from the core of the site. In numerical terms, Calakmul remained inferior to Tikal, despite being among the richest Maya cities. It housed an estimated 50,000 people, while the entire kingdom had a population of 200,000. In contrast, Tikal alone was home to almost half a million people (Braswell et al, 2005:171). Each city-state greatly eclipsed any other Maya polity at the time.

The history of the Maya during the Early to Late Classic (250-909), is often associated with Teotihuacán, notably during the Early Classic phase (250-550). The long-enduring antagonism between Calakmul and Tikal was fueled by Teotihuacán and its regional proxies. Teotihuacán reached its peak in 450 when it was the center of a powerful culture whose influence extended through much of the Mesoamerican region. At that time, the city was a large metropolis covering twelve square miles and may have housed a population numbering over a hundred thousand people. It was built by Náhuatl speaking people on Otomi territory, on the central plateau of Mexico. As Duverger explains “the city’s founding lords were Náhuatl who conceived their ceremonial center according to their world view as an affirmation of their political power and in homage to their gods” (2007:366). The people of the city, the teotihuacanos, were of many ethnic origins, but the majority were Nahuatl speaking of Chichimec ancestry who migrated from Mexico’s northern dry lands. They were noted “for adopting other cultures.” As far as is known, at the beginning of their migration small groups headed south and settled in the valley of Mexico and then, through time, moved further south. Even though they were great warriors, they did not initiate wars of conquest but settled near towns sharing their expertise while working with locals. Slowly integrating their experience and beliefs into the community. As skilled traders, they spread throughout Mesoamerica. As Shele and Freidel underline, “…later, what was exchanged was not just goods, but a whole philosophy. The Maya borrowed the idea and the imagery of conquest war from Teotihuacán and made it their own” (1990:159).

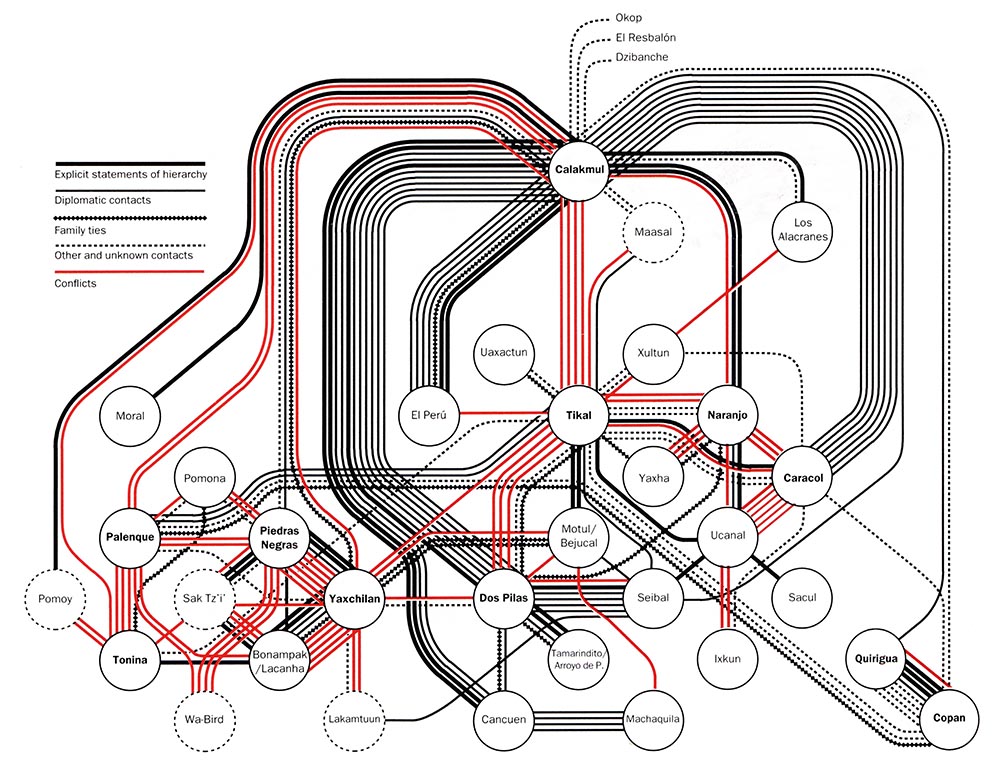

At the heart of the antagonism with the kingdoms of Mesoamerica was a linguistic, cultural and spiritual divide between the Mexican highland culture, its policies, its gods and those of the Maya lowlands. So let us briefly step back in time and find out about alliances, misalliances and their often-tragic consequences in this complex web of antagonism and treachery spanning generations of wars and through proxies, for political and resource control. Foremost, as Demarest underlines, was the religious and political structure related to the concept of k’uhul ajaw, or holy lord. The unconditional spiritual and secular powers held by a holy lord, were believed to be granted by the gods to hold together the social and spiritual structure of Classic Maya societies through faith, ritual and patronage (2013:25); a concept that will ultimately be associated to the culture’s downfall.

The third player in this ongoing tragic story is Tikal, a name-place that is relatively recent and derives from the Maya ti or “place of” and k’al or “spirits” meaning “place of spirits.” The powerful dynasty headed by kuhul ajaw Chak Tok Ichak “Jaguar Claws” rose in 300 and became an unrivaled metropolis. In 426 he was followed by Caan Chac “Stormy Skies” who recast Tikal into an aggressive military and commercial powerhouse. It was during that time that altars and stelas were built, commemorating the city’s military and religious successes. By 500, the city and townships grew to over twenty square miles, and a population estimated at over 90,000 souls. It is during Ah Kakaw “Cocoa Lord” tenure in 682 and his successors, that the most important structures were built, such as Temple I, II, III and IV. The city, at its apogee during the late classic extended across 65 square miles and more than 4000 buildings, including temples, palaces and houses large and small, teaming with life.

In the early Maya world, a single large city tended to be in control. Tikal moved into this position of dominance in the Late-Middle Preclassic (600-350BC) while, about forty miles to the south, El Mirador and Nakbè, in Guatemala’s Peten declined. It was at the end of that time that Calakmul grew to challenge Tikal for its resources but, above all, for its key regional position and political influence. Harrison offers reasons for this web of repeated conflicts. The city of Caracol, in today’s Belize, attacked Tikal sixty miles to its northwest after an earlier period of alliance based on familiar interaction. The event leading up to this war is a textbook example of political intrigue. The record shows that in 546, under the auspices of the reigning king of Calakmul, there had been ongoing conflicts driven by rivalry over the dominance of trade routes in the Usumacinta River watershed (2000:121).

On the eastern side of the watershed are rivers leading toward the Caribbean coast, while to the west are drainages and rivers leading to the great Usumacinta River, which flows directly to the Gulf of Mexico. As Scarborough notes, the Usumacinta River also receives drainage from the uplands to the west. In other words, most of the Maya lowlands are divided by drainage at this strategic point, a place that would have to be crossed when trade routes extended from the west to the east side of the Yucatán Peninsula (1993). Tikal sat astride this east-west peninsular divide and was determined to surround Caracol with its own network of allies to control this key trade route. From the second half of the sixth century to the late seventh century Calakmul’s aggressive persistence gained the upper hand by allying with or defeating Tikal’s allies, although it failed to stifle Tikal’s power and influence. Tikal was able to turn the tables on to its great rival in a decisive battle that took place in 695 when it was able to overcome Calakmul’s most important allies. But the rivalry between the two cities was grounded on more than competition for resources. Their dynastic histories reveal that it had an ideological foundation. Different origins and intense competition between the two powers had an ideological grounding beside trade routes.

Calakmul’s dynasty seems to have derived from the great Preclassic Maya city of El Mirador in the Peten, while Tikal’s dynasty was supported by Nahuatl power from Teotihuacán. However, who were those all-powerful lords from the powerful northern city? As Martin and Grube underline, few of the so-called entradas or “forced entrances” that took place in the region in 378 had such a transforming effect on the Maya lowlands, as the arrival at Tikal of Teotihuacán’s army headed by Siyaj K’ak” (Fire-is-Born), on 31 January of that year. The invading army was under Teotihuacán’s intriguing lord Jatz’om Kuy or “striker owl,” referred as Spearthrower Owl in the literature (364-439), who led his kingdom in subduing the Maya area, including the coup d’état at Tikal in 378.

This aggression was supported by a Teotihuacán dissident political faction of the Feathered-Serpent, led in all probability by the city’s head of the army Siyaj K’ak’. Of note is that this “forced entrance” may not have been directed by the state government but by this dissident faction which was later thrown out of the city. The Feathered-Serpent Pyramid was burned, all its sculptures were torn from the temple, while another platform was built to obliterate the original front of the building (Stuart, 2014). This episode would bring not only Tikal, but a whole swath of the Maya in Yucatán’s south-central area, into Teotihuacán political, cultural and economic sphere.

Scholars note the arrival at Tikal of the group headed by Siyaj K’ak’ and his army, which was recorded eight days earlier at the city of El Peru, forty-nine miles west from Tikal whose closest neighbor, Uaxactún (uaxac-eight, tún-stone), twelve miles away, had been unable to sustain the regional competition and had fallen under Tikal authority in about 354. Of note is that Uaxactún was merely Siyaj K’ak’ steppingstone in the Tikal’s conquest of 378. Upon Tikal’s defeat, Siyaj K’ak’ met the lord of the realm Chak Tok Ich’aak.I, (Jaguar Paw.I, 360-378). On that same day, Siyaj K’ak’ killed the Maya lord and his entire lineage. The kingdom’s court was replaced by a new male line that seems to have been drawn from the ruling house of Teotihuacán. Stela.31 at Tikal describes that in 379 Siyaj K’ak’, who may have been the son of Spearthrower Owl, was installed as king. The new king introduced Teotihuacán-style imagery in the city’s iconography and architecture, such as the Mundo Perdido complex, a smaller version of Teotihuacán ciudadela. Siyaj K’ak’ also appears in Rio Azul in 393 indicating that the central Peten was then firmly in his hands” (Demarest, 2011, 2000:29). It probably is at that time that the deadly atlatl or dart thrower was introduced in Maya lands by the Mexicans to local friendly armies.

The kingdom of Calakmul was at least as large in area and population as any other Late Classic polity in the central Maya lowlands, including Tikal (Fletcher, Gann, 1992; Folan, 1988). Scholars believe that the Ka’an dynasty was not originally from Calakmul, for recent epigraphic discoveries at Dzibanchè and Xunantunich in Belize, provide evidence that the toponym of Kaanu’l (k’uhul kaanu’l ajaw), the “Snake King” emblem glyph, was in fact the ancient name of Dzibanchè. In 636-640 the hub of the Kaanu’l hegemony moved to Calakmul, in all probability, to establish a more strategic location for the capital of the realm. Like Tikal, the kingdom survived the demise of older cities but was abandoned at the end of the Early Classic period (500-600 AD). As scholars underline, Calakmul’s earliest development remains stubbornly uncertain for, the record shows that the first settlement at Dzibanché housed groups of people who settled from the Nakbè area in today’s Guatemala. As Martin and Grube point out, we do have a lengthy list that traces the city’s royal line back to a “founder”, but in many ways this document poses more questions than it answers (2000:116-137).

The Maya Classic period (250-950) was the scene of intense rivalry for control of resources and, specifically, over transport routes through choke points such as mountain passes and river crossings, keys at the heart of either political alliance or antagonism. Demarest emphasizes that trade routes between inland and coastal areas, and especially between the highlands and lowlands, seem to have been important in most periods for the location and success of major centers (2004:162). In 537 Calakmul conquered Yaxchilan on the north side of the Usumacinta river and allied itself with anti-Tikal cities such as Caracol, El Perú and El Zotz (Braswell et al, 2005). Control through proxies of this major trade artery of the lowlands, gave the polity an advantageous strategic position covering accesses east and west of Tikal.

Teotihuacán appears to have been the proxy in this unending Nahua-Maya antagonism for its own and allies political and resource control. Its economic and military policies over the Pacific coast and hinterland chiefdoms, from central Mexico to Guatemala have growing over years, witness its early presence at Kaminaljuyu and Takalik Abaj (Guatemala). Many luxury goods for the elite, such as macaws and quetzals feathers, pyrite from the tropical south, precious jade from the Motagua River valley of Guatemala and non-exotic commodities such as obsidian, cocoa and salt traveled on the Usumacinta-Pasión river drainage. Obsidian was among the most useful in positing trade routes because there are only a few major outcrops of this volcanic glass in the highlands of Guatemala and Mexico. Of note is that Tikal zone of influence was close and at times overlapped that of Teotihuacán, giving it and its proxies a favorable strategic position and control of territories to its east and west, as well as trade over the Usumacinta River.

Over two hundred miles from Tikal, Palenque traded and probably had political contacts with the powerful metropolis of central Mexico through Tikal. Calakmul perceived Palenque as a Mexican surrogate in the Maya heartland for its close relationship with Tikal. The perception was likely correct: a life-size, stucco figure of an atlatl-armed god of rain Tlaloc in Palenque’s Temple.XX, is a testimony to the kingdom’s close association with Tikal. Incidentally, Tlaloc was the rain god common to both Maya and Nahuatl cultures. This political stand would explain Calakmul’s persistent and violent antagonism towards Palenque. Lakamha’ (Palenque) paid a heavy price for this relationship with defeats and burning. Lakamha’s lord Pakal got his revenge against the Ka’an kingdom as seen in House.C’s of the palace west court, where life size limestone monoliths show six war chiefs (sahals) captured in battle in 659. They are shown bound for execution, facing House.A’s carved steps across, whose glyphs recount Palenque’s defeat and burning in 599 and again 611 by Calakmul regional proxies, such as Pomona forty miles away.

Over the years, both Calakmul and Tikal, with equivalent resources and political influence, repeatedly challenged each other supported by their own local network of operatives. Between the sixth and eighth centuries (537-744), each kingdom in turn gained the upper hand over the other for control of trade choke points such as mountain passes and rivers. The conflicts between Tikal, Calakmul and their allies concurrent with increased construction of large well-fortified citadels to protect strategically significant trade routes. One of the most notable forts, La Cuernavilla, was constructed between Tikal and El Zotz (Tom Clynes-NatGeo, 2019). Recent LIDAR research found 65 miles of road-like causeways and 37 miles of interspaced defenses over hilltops (CWA,1996).

Teotihuacán’s influence in the century between 650-750 declined and vanished at the end of the period. For lack of tangible record, we are uncertain as to why this powerful city of over 100,000 people with districts housing ethnic groups from across Mesoamerica collapsed within the last fifty years of the eighth century. Braswell notes that Teotihuacán-inspired ideologies and motives persisted at Maya centers into the Late Classic, long after Teotihuacán itself had collapsed” (2003:7). Its long twilight was associated with increased conflicts between Maya polities as well as socio-economic and political upheavals.

Calakmul went on to conquer Naranjo in 546. Tikal and its allies were not destroyed but suffered major losses and declined after the war ended in 572. The end of the Early Classic period falls between 550 and 600 saw a major defeat of Tikal in 562 recorded on a carved altar, after an earlier period of alliance based on familial interaction. The defeat was again initiated in conjunction with Calakmul’s allies, and with-it Tikal fell silent for 125 years, a period referred as a “hiatus” by scholars. During that period, there were no well-known carved monuments, no inscriptions of any kind recorded in the city. The hiatus spans from 557, the last recorded dated Stela.17, to 682. During that time, Tikal nobility gave way to a meager caricature of its former glory in the archaeological record. The oppressors permitted only one tomb of wealth – Burial 195, the resting place of the twenty-second successor in the Tikal dynasty. Never permitted to erect public monuments, this lord was at least allowed the privilege of a royal burial and a dignified exit to the Otherworld, perhaps to offset the humiliation of being denied his place in history (Schele, Freidel, 1990:174). The end of the hiatus is recorded with the 26th ruler Hasaw Chan K’awill (682-734), who won a battle against Calakmul in 711, and was the first to restore a written record of the city. As Tikal regained strength from its long silence, Teotihuacán’s influence was fading amid internal conflicts and warfare and by then, had dissolved into oblivion.

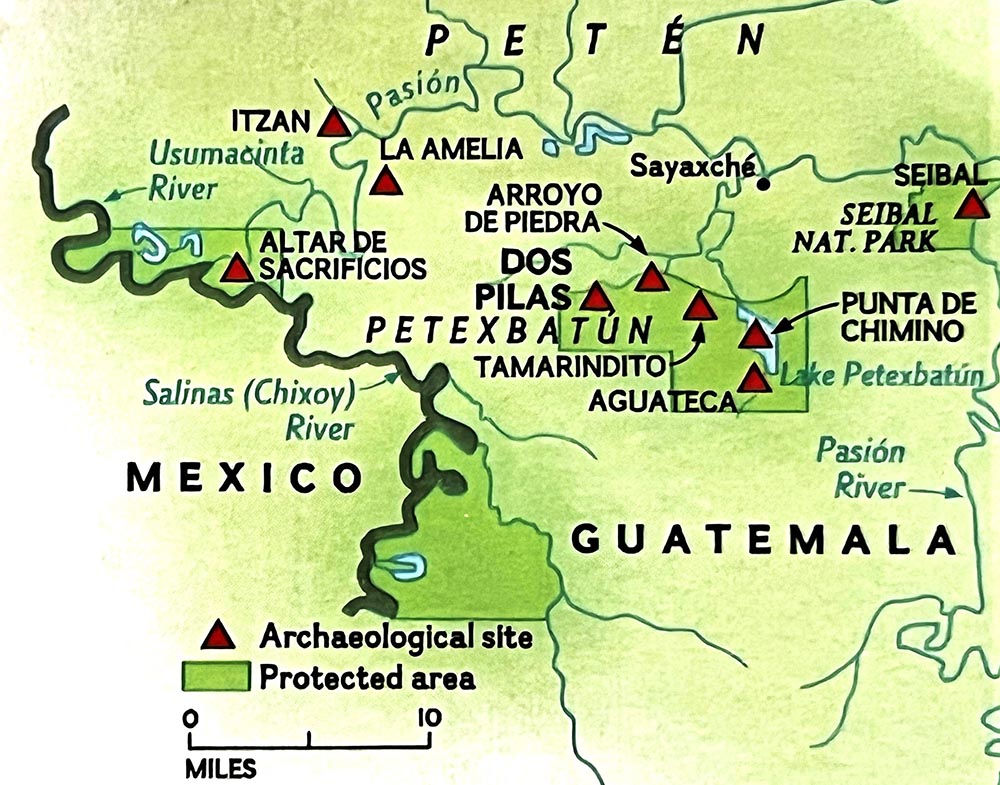

The historical antagonism regained strength following Tikal’s revival with king Muwaan Jol.II (655-680) who sent his son B’alaj Chan K’awill to Dos Pilas where he established a military outpost to defend Tikal’s wider zone of control. At first, B’alaj Chan K’awill (648-692), maintained loyalty to Tikal, and as time went on fighting erupted once more between Tikal and Calakmul. B’alaj Chan K’awill initially fled into exile but then opted to switch sides in 658 (J.N. Wilford, 2002). The so-called second war between Calakmul and Tikal lasted from 648 to 695. One of the notable battles was Dos Pilas, built by Tikal renegade nobles, some sixty-five miles away. Among renegades was Tikal’s ruler “Shield Skull,” likely the brother or half-brother of Ruler.1, who waged war against his sibling, was captured and sacrificed. The stunning upset established the power of the breakaway kingdom. Now a separatist realm led by B’alaj Chan K’awill, began a destructive “proxy war” against his old mother city in 672. Tikal retook Dos Pilas, but B’alaj Chan K’awill escaped to Aguateca. From there, he rallied his followers and allies, and launched a counter-offensive, defeating Tikal’s army in a major battle in 679. After his victory, B’alaj Chan K’awill captured and sacrificed Tikal’s ruler, his own brother (Wilford, 2002). From then until 695, three years after B’alaj’s death, Calakmul dominated Tikal. However, Tikal, under the leadership of Jasaw Chan K’awill (682-734), won a major battle with Calakmul in 711, effectively ending the conflict. Weakened militarily and now deprived of its martial reputation, Calakmul lost its northern provinces and collapsed.

Dos Pilas and then Aguateca, in Lake Petexbatún region of northern Guatemala, were founded in about 640 by a prince who had left Tikal. The second and third rulers waged wars of conquest and dominated the territory between the Pasión and Chixoy rivers. During that time, Dos Pilas experienced a period of expansion, conquering several other small city-states. By 761, however, their vassal Tamarindito rebelled and killed Dos Pilas, Ruler.4 (name unknown), causing the nobility to relocate to the naturally fortified site of Aguateca, which was already acting as the twin capital of the kingdom. The chaos that led to the kingdoms’ collapse of the north started the warfare that would consume the region and spread south, Demarest (1993:95-111). When Dos Pilas was besieged, residents threw up fortifications around the city, ripping down facades of temples and palaces for stones to raise two circular walls topped with wooden palisades. A cleared corridor between the walls likely served as a killing ground. The inner wall pierced the sacred royal palace and bisected its stairway with hieroglyphs recounting Ruler.4 accession, which underline the survivors’ desperate effort to resist. Seeking safe-haven, farmers moved into the plaza, building crude huts on cobblestone platforms, and planting small gardens to grow food; to no avail, the city was burned.

A few hundred residents remained in the Dos Pilas ruins until the early ninth century when it was abandoned. The Dos Pilas dynasty survived until the early 800s. The last recorded date in Aguateca is 830, but may have taken place a few years later when, during the reign of Tan Te’ Kinich the city was invaded and burned. Its ruins show three defensive moats that were cut across the neck of the Chimino Peninsula on the edge of Laguna Petexbatún. Archaeologists surmise that Punta de Chimino, on the western side of Lake Petexbatún, was the last refuge of the dynasty founded at Dos Pilas.

Similarly, Tikal, and most of the Maya cities were destroyed in the Maya collapse. Demarest pertinently asks, “why do civilizations follow a trajectory that in general fail to stabilize?” and “why is success in a complex political system unable to achieve equilibrium or sustainability?” He further remarks, “there is still disagreement as to the nature and causes of the end of the lowland Classic Maya kingdoms. Investigations, however, reveal a clear and consistent, albeit complex, sequence of events in the Petexbatún (2013:249).

At the heart of recurrent antagonisms between Maya kingdoms, however, was the unique conception of a holy lord (K’uhul Ahaw) who held absolute religious and secular powers. Through generations, this model of rulership was poorly structured to respond to change. Through time, the top-heavy government construct made up of a growing nobility, priests, civil and military administrators and their families, increased the burden on commoners and peasants’ daily living which became counterproductive (Demarest, 2004:246). Farmers slowly but again and again moved away from their overworked lands because they could no longer produce enough food for a growing demography. Expanding tillable lands were encroaching on those of neighbors which multiplied antagonism and clashes. Access to water magnified the problem, especially in times of scarcity. Furthermore, young men were often required to join the military to ward off upending threats or were needed for public works and could not tend to their crops. Women in towns and villages, beside attending to their families’ daily needs, were tasked to help war widows and the elderly. Their aging parents or family members then had to work in the fields. However, depleted agricultural resources, deforestation, and frequent droughts oftentimes led to lower crop output or complete failure.

The end of the Terminal Classic (830-950), as Schele and Freidel underline, witnessed a major transformation of the Maya world, one that would leave the southern lowlands a backwater for the rest of Mesoamerican history. Regardless of the way the southern kingdoms met their doom, it is the staggering scope and range of their collapse that stymies us. This is the real mystery of the ancient Maya, and it is one that has long fascinated Mayanists and the public (1990:379). Fragmentation of political authority was accompanied by a slow decline in population and construction activity. That period should, therefore, be referred to as the dimming or exhaustion of the Late Classic society, before it could reinvent itself with new generations in the northern Yucatán peninsula, and the rise of the Early Post Classic, 950-1200.

References – Further Reading:

Concepcion, O. Rodriguez, R. Liendo Stuardo, 2016 – Los Antiguos Reinos Mayas del Usumacinta

Daniel Graña-Behrens, 2016 – Emblem Glyphs and Political Organizacion in Northwestern Yucatan (300-1000).

Schele and D. Freidel, 1990 – The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya

Peter D. Harrison, 1999 – The Lords of Tikal

Arthur A. Demarest, 2004 – Ancient Maya, the Rise and Fall of Rainforest Civilization

Linda Schele et all.2003 – The Maya and Teotihuacan

Joyce Marcus, 1976 – Emblem and State in Classic Maya Lowlands

Patrick T. Culbert, 1973 – The Maya Downfall at Tikal

Lisa J. Lucero, 1999 – Classic Lowland Maya Political Organization

Kai Delvendahl, 2008 – Calakmul in Sight: History and Archaeology of an Ancient Maya City

Joyce Marcus, 2004 – Maya Political Cycling and the Story of the Ka’an Polity

Stephen D. Houston, 1996 – Hieroglyphs and History of Dos Pilas, Dynastic Polics of the Classic Maya

Contributor’s Bio:

Freelance writer, researcher and photographer georgefery.com addresses topics, from history, culture, and beliefs to daily living of ancient and today’s communities of Mesoamerica and South America. His articles are published online at travelthruhistory.com, ancient-origins.net and popular-archaeology.com, in the quarterly magazine Ancient American (ancientamerican.com), as well as in the U.K. at mexicolore.co.uk.

The author is a fellow of the Institute of Maya Studies in Miami, FL instituteofmayastudies.org and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org. Also a member in good standing of the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org, the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org, the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. americanindian.si.edu, and the NFAA – Non-Fiction Authors Association nonfictionauthrosassociation.com.

Contact:

Georges Fery – 5200 Keller Springs Road, # 1511, Dallas, Texas 75248 – T. (786) 501 9692 – gfery.43@gmail.com and www.georgefery.com

Photo credits:

Ph.1 – Calakmul, Str.I @planet-mexico.com

Ph.2 – Calakmul, Str.2 @georgefery.com

Ph.3 – Teotihuacán, Pyramid of the Moon @georgefery.com

Ph.4 – Tikal, Temple.I, Main Plaza @georgefery.com

Ph.5 – Classic Maya Linkages @S.Martin, M. Coe in ArqueoMex Vol. 47:P41

Ph.6 – Major Trade Routes, Yucatán and Petén @Luis F. Luin in Demarest, 2010:159

Ph.7 – Petén-Petexbatún Area @Demarest in Maya Kingdom, NatGeo, 1993:95-111

Ph.8 – Calakmul, Temple.1 @georgefery.com

Ph.10 – Piedras Negras, K’uhul Ajaw’s Throne @georgefery.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.