by Mary Anne Broccolo

It’s late evening as our taxi bounces us through the streets of New Delhi from the airport to our guesthouse. It’s a shock to my western senses, this introduction to the country in which I have just arrived. We are surrounded by a cacophony of honking cars as we dodge the onslaught of traffic, vehicles of all sorts driving haphazardly in every direction. We seem to narrowly escape collisions with rickshaws, stray dogs and cows. Walking on the side of the road is a man dressed in a ragged loin cloth and a long grey beard, skin covered in ashes. The air stinks. I laugh out loud. It’s both thrilling and fascinating, this dissonant symphony taking place around us. Noise, traffic, masses of people and animals, strong smells. So this is India, I think.

After a few final honks and swerves, our driver pulls in behind the guest house and I am shown to my room. Thankfully, the car horns fade into the night and sleep comes.

It’s September 2004, and I have arrived to meet seven others, including our Vancouver guides, Rasik and Melinda. The trip was originally planned as a yoga tour but the yoga teacher has cancelled for health reasons. Still, I am filled with excitement to be in this strange country, so different from any others I’ve visited. There would be no yoga or meditation, but we would be embarking on a week-long trek in the Himalayas to a source of the Ganges, that most sacred of Indian rivers.

But first, we spend several days in New Delhi visiting historic sites and monuments, but it’s India so we also see cows pulling old-fashioned lawnmowers to cut the lawns. We shop too, travelling by auto-rickshaw.

We dine in the majestic Imperial Hotel, enclosed by walls and guarded by handsome doormen dressed in white uniforms, looking as if they’d been standing there since the days of the Raj. We also dine in Old Delhi where we are entertained by dancers performing regional dances. During the taxi ride to Old Delhi, I spot a legless man on a low wooden cart, pushing himself along with his hands, recalling an image from Rohinton Mistry’s novel, “A Fine Balance.” There are also entire families with babies and small children living on the sidewalks of Old Delhi among the garbage, feral dogs, cows and dung.

It’s soon time to head for the mountains and we leave New Delhi, travelling by train to Dehradun where we’re greeted by Chile and Neelu, bearing garlands of marigolds which they drape around our necks. Chile and Neelu will be our chief guides and caretakers in the Himalayas. After refreshment of chai and sweets, we board taxis for the two hour drive up steep mountain roads to Mussoorie, an old hill top fortress dating from the days of the Raj. Mussoorie is also a popular holiday resort for the Indian people, and it’s bustling when we arrive.

Staying two nights in Mussoorie to acclimatize to the increase in altitude, we hike in the surrounding forests. The elevation at Mussoorie is about 6,300 feet. It’s an interesting city, a reminder of India’s many dichotomies. From our guest house, we have a stunning panoramic view of the spreading green valley far below us, but it’s interrupted by a garbage slum situated on the higher edge of the slope. Families live there amid the garbage.

We travel by jeep further into the Himalayas to Uttarkashi, accompanied during the drive by Indian folk music on the tape deck. The roads are treacherous – narrow and winding -and there are many large military vehicles coming from the other direction, forcing us to hug the mountain side as they edge past. In case anyone driving on this road should forget to pay attention, entertaining signs line the side of the road, warning us: “Peep peep, don’t sleep”, “Road is hilly, don’t be silly”, “Awake today, alive tomorrow”, “Steady your nerves, before the curves”, “After whisky, driving risky”.

As we drive through this region, I begin to form an idea of India’s place in today’s world, with one foot in the modern era but the other still in an ancient way of life. There are women and young girls carrying heavy loads of brush on their backs, while men cluster in groups drinking and chatting. Nomadic hill tribes camp on the verge of the road while journeying down from their higher summer territory to their winter territory in the low valleys, together with their cattle, buffalo and goats. We are told that their way of life is threatened by the modern invasion, which can bring discontent when they see how others live.

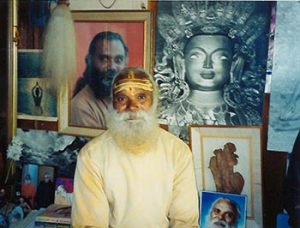

In the village of Uttarkashi, we visit the local Swami, whose name we never discover. He is an intelligent, well-spoken and educated man, and speaks English well. We are invited into the home that he shares with a servant-follower and he speaks with us, showing wisdom and common sense in his words. And yet I don’t remember those words.

In the village of Uttarkashi, we visit the local Swami, whose name we never discover. He is an intelligent, well-spoken and educated man, and speaks English well. We are invited into the home that he shares with a servant-follower and he speaks with us, showing wisdom and common sense in his words. And yet I don’t remember those words.

The next day, we drive on to Gangotri, the last village on our route, passing on our way a place on the road where sixty people died recently in a monsoon-induced mudslide, something I remembered seeing in the news.

We rest in Gangotri, visiting Swami Sunderanand, who allows us to have photos taken with him in front of his hut. Swamiji does not speak English but our guides are able to translate for him. He shows us a large and beautiful book about the Himalayas, filled with photographs he has taken during his many years of wandering in the mountains. He is selling this book to raise funds for a meditation retreat. Later that evening, we attend services at the local Hindu temple, standing with the crowd just outside the temple. Although two of our group go inside to have red paint dabbed on their foreheads, a ritual that reminds me of communion in a Christian church, I feel more comfortable remaining at a respectful distance outside.

We rest in Gangotri, visiting Swami Sunderanand, who allows us to have photos taken with him in front of his hut. Swamiji does not speak English but our guides are able to translate for him. He shows us a large and beautiful book about the Himalayas, filled with photographs he has taken during his many years of wandering in the mountains. He is selling this book to raise funds for a meditation retreat. Later that evening, we attend services at the local Hindu temple, standing with the crowd just outside the temple. Although two of our group go inside to have red paint dabbed on their foreheads, a ritual that reminds me of communion in a Christian church, I feel more comfortable remaining at a respectful distance outside.

In the morning, we finally set out for our first day of trekking, about 8 kilometers of gradual ascent on a path following the Bhagirathi River to Chirbhasa, our first campground. The Bhagirathi River joins another river farther downstream to become Mother Ganges. Porters, mostly young Nepalese men, many of them teenagers, carry our duffel bags, food and camping gear. Some of them support entire families back home. We wear hiking boots, but they wear light sandals, nimbly passing us soon after we leave. There are eight of us from Canada, as well as our two Indian guides and cooks, but there are eighteen porters.

At Chirbhasa, we must visit the local swami since Chirbhasa is his campground. He is a doubtful swami and he has been nicknamed the “Thong Baba” by our guides from Vancouver, who have met him before. The Thong Baba believes in minimal clothing and the next morning a couple of us are dismayed to inadvertently spot him performing his morning ablutions by a pool behind his hut. We creep away. When we visit him, he speaks at great length, loudly and with a hint of arrogance, not allowing time for translation, but we sit before him on the ground with our legs crossed and try to look attentive. We are told later that he was angry because his followers had deserted him.

The next day, we move on to Bhojbhasa, another campground, but the heat of the day and the thin mountain air make the four kilometres feel more like ten and our pace is very slow. We are grateful for the refreshment stops at tea dhabas, which seem to appear periodically along the trail, offering chai and couches in tents for resting. As usual, our camp is ready for us when we arrive. There are no modern facilities at these places and it’s difficult to find large rocks to hide behind but we find that the staff have taken pity on us and built an “outhouse”. Three of us go to check it out. Surrounded by a tarp flapping in the breeze, we find two flat stones on either side of a miserably small hole in the sand, about the size that a cat might scratch but our uncontrolled laughter makes their efforts worthwhile, although perhaps not in the way they intended.

The next day, we trek to Gaumukh, the glacier from which the Bhagirathi River we have been following trickles, and then we begin the truly challenging part of our journey – the ascent to Tapovan over the moraine of the glacier that feeds this river. Our final ascent is several hundred meters and although I am a hiker, I begin to wonder if I will die before I get there. Every two steps seem to require a rest. Close to the top, I see friendly faces peering over the edge, calling to cheer me on. We camp on the plain at the top, below the peaks of the Bhagirathi Sisters and Mount Shivaling, under a full moon.

The next day, we trek to Gaumukh, the glacier from which the Bhagirathi River we have been following trickles, and then we begin the truly challenging part of our journey – the ascent to Tapovan over the moraine of the glacier that feeds this river. Our final ascent is several hundred meters and although I am a hiker, I begin to wonder if I will die before I get there. Every two steps seem to require a rest. Close to the top, I see friendly faces peering over the edge, calling to cheer me on. We camp on the plain at the top, below the peaks of the Bhagirathi Sisters and Mount Shivaling, under a full moon.

I am exhausted, sick and have a headache, and snuggle into my sleeping bag, where my tent-mate, also sick, has already snuggled into hers. Chile brings hot bowls of soup to our tent, but we are finally encouraged to join the others in the dining tent. It’s freezing cold. While days can be hot, the nights are bitter. We are at an elevation of 14,500 feet! I finally realize that I must be experiencing altitude sickness.

The next day, without much enthusiasm, our group attempts a short walk, then we visit the Shimla Baba (also called Birdman) who resides in a rustic hut next to our campground. He is happy to have visitors, serves us juicy fresh apples and talks to us briefly before sending us on our way with a warning that it will soon rain. He’s right. Shortly after we leave the glacier, it begins to rain. It’s a much faster journey now and we only camp once before returning to Gangotri, where we began. But before we arrive in Gangotri, we are required to step aside to allow a large group of about 300 pilgrims who are travelling in the other direction to the glacier at Gaumukh. An Indian woman riding a donkey catches my eye as she passes and greets me with the words “Namaste, Hari Ohm.” I think she looks like an Indian princess.

From Gangotri, we return to Uttarkashi, and then Mussoorie, with parties in both places to say goodbye to our Indian friends. We dance with them and they try to teach us Hindi dancing. A few days later, we arrive back in New Delhi.

From Gangotri, we return to Uttarkashi, and then Mussoorie, with parties in both places to say goodbye to our Indian friends. We dance with them and they try to teach us Hindi dancing. A few days later, we arrive back in New Delhi.

Our trip is ended and we finally part ways but I must remain in New Delhi one more day. I want to see the Taj Mahal. I book a coach tour to Agra, city of the Taj Mahal. I gaze at the magnificent building while a guide talks about its history, but I am so mesmerized by the thick, inch long tufts of coarse hair sprouting from each of his ears that all I can recall is that a prince built it for his wife.

This trip to India was almost accidental but it turned out to be one of my most memorable travel adventures. In some ways, it has made me change my way of thinking about the world. Everywhere we went, we seemed to see some the most appalling living conditions, yet people managed. They carried on. They lived together in one of the world’s most crowded impoverished countries and yet they warmly welcomed us, showing interest and kindness. I came to admire their resilience and fell in love with their vibrant country.

If You Go:

Ghorepani Ghandruk Trek ( Poon Hill circuit, Annapurna sunrise view trek)

About the author:

After a career as a legal assistant/paralegal, Mary Anne is happily retired and enjoys doing what she loves best – going back to school taking a large variety of courses through Simon Fraser University’s seniors program, walking, hiking and reading a lot, and finally learning to write her stories.

Photographs:

Gaumukh Gangotri glacier by Atarax42 under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license.

Photos #2 – #5 by Mary Anne Broccolo

6-Day Himalayan Ladakh Tour: Buddhist Monasteries Lakes and Yaks from Leh

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.