by Darlene Foster

The road appears to be going nowhere as it winds its way around the precipices, over gorges and through rocky landscapes. Tired of the busy beach towns of the Costa del Sol, we turned off the highway at a sign indicating Istan, a while ago. We round another hairpin curve, still no village in site. Have we taken a wrong turn? Should we turn back? Our inquisitive minds compel us to go further up into the desolate cliffs. Another twist and turn and there it is, a white village nested in the arms of a mountain.

Created for mules and packhorses, the narrow streets are steep and best experienced on foot. We park the car and explore this village of Moorish roots dating back to 1448. A map painted on a whitewashed wall provides a guide around the historic section. We wander the almost perpendicular avenues, passing quaint tiled courtyards decorated with flowers and greenery in terracotta pots. The pristine white houses accented with charming old wooden doors are postcard worthy. We soon reach Juana de Escalante Passage, the remainder of the centre of the old Muslim town, tucked in a side street.

Created for mules and packhorses, the narrow streets are steep and best experienced on foot. We park the car and explore this village of Moorish roots dating back to 1448. A map painted on a whitewashed wall provides a guide around the historic section. We wander the almost perpendicular avenues, passing quaint tiled courtyards decorated with flowers and greenery in terracotta pots. The pristine white houses accented with charming old wooden doors are postcard worthy. We soon reach Juana de Escalante Passage, the remainder of the centre of the old Muslim town, tucked in a side street.

This was the site of a Moorish rebellion in 1568. The niece of the cleric, Juana de Escalante, stopped the rebels by throwing stones at them from the tower until aid came from Marbella. All that remains is the site the tower once stood on, the round archway and the courtyard through which horses passed through on the way to the stables. Standing there I sense the walls could tell many stories over the centuries. I look down and observe the detailed tile work on the ground. It is a work of art.

This was the site of a Moorish rebellion in 1568. The niece of the cleric, Juana de Escalante, stopped the rebels by throwing stones at them from the tower until aid came from Marbella. All that remains is the site the tower once stood on, the round archway and the courtyard through which horses passed through on the way to the stables. Standing there I sense the walls could tell many stories over the centuries. I look down and observe the detailed tile work on the ground. It is a work of art.

Istan remained in existence due to its distance from the coast. After the Christian conquest in the 15th Century, Arab settlements near the Costa del Sol were destroyed due to their close proximity to Africa. The mountain villages however, were not considered a threat.

Throughout the village is a series of water fountains providing fresh water for the inhabitants over the centuries. The fountains are as attractive as functional; decorated with blue and white tiles, some painted with scenes of the area. The mountain water is prized for its purity.

Throughout the village is a series of water fountains providing fresh water for the inhabitants over the centuries. The fountains are as attractive as functional; decorated with blue and white tiles, some painted with scenes of the area. The mountain water is prized for its purity.

There are a few interesting tapas bars and restaurants in the town. We stop for lunch at the Entresierras Bar and are encouraged by the friendly waiter to sit outside overlooking the gorge and part of the village. The cheerful villagers all speak Spanish and are eager to please. I enjoy a hearty plate of assorted local cheeses and my husband has a fresh fruit salad. A perfect lunch. I am so happy we persevered and found this little out of the way place so well preserved and full of character and history.

Browse Costa Del Sol Tours Now Available

If You Go:

Istan is tucked away beneath the Sierra Blanca at the head of the valley of the rio Verde, close to the Serrania de Ronda hunting reserve. To reach it, leave the N-340 coastal highway 5 kilometres south of Marbella just beyond the Hotel Puente Romano. The road is good but long and windy – about 15 kilometers.

About the author:

Darlene Foster is a dedicated writer and traveller. She is the author of a series of books featuring Amanda, a spunky young girl who loves to travel to interesting places such as the United Arab Emirates, Spain, England and Alberta, where she always has an adventure. Darlene divides her time between the west coast of Canada and the Costa Blanca of Spain. www.darlenefoster.ca

All photos are by Darlene Foster

The ruin of Montségur perches on a hilltop in the foothills of the Pyrenees. My arduous climb to this lonely crag is rewarded with panoramic views of lush hillsides dotted with purple blooming wild sage and silent sheep. All that remains of the castle are crumbling walls and part of a keep. A sighing wind whispers over the walls.

The ruin of Montségur perches on a hilltop in the foothills of the Pyrenees. My arduous climb to this lonely crag is rewarded with panoramic views of lush hillsides dotted with purple blooming wild sage and silent sheep. All that remains of the castle are crumbling walls and part of a keep. A sighing wind whispers over the walls. In contrast to the desolate loneliness of Montségur castle, Mirepoix is a bustling market town. Pastel coloured, half-timbered houses above wood frame arcades line the main square. Gargoyles on the church supervise the crowds around the curlicue adorned market. At the other end of the square sits the 14th century town hall. Each decorative wooden beam has a different carved head, demon, or animal.

In contrast to the desolate loneliness of Montségur castle, Mirepoix is a bustling market town. Pastel coloured, half-timbered houses above wood frame arcades line the main square. Gargoyles on the church supervise the crowds around the curlicue adorned market. At the other end of the square sits the 14th century town hall. Each decorative wooden beam has a different carved head, demon, or animal. On the opposite end of the spectrum from Montségur’s crumbling castle are the immaculately restored walls, bastions, and towers of Carcassonne’s Cité. Viewed across vineyards, the fortress stands as if from a fairy tale. Fortified since Roman times, Carcassonne was a Cathar stronghold in the Middle Ages. In the 1800s, Viollet-le-Duc imaginatively restored the double walls and the chateau they shelter. At a time when so many of France’s monuments were being neglected, he rallied for restoration. The project took fifty years and sadly, he did not live to see its glorious completion.

On the opposite end of the spectrum from Montségur’s crumbling castle are the immaculately restored walls, bastions, and towers of Carcassonne’s Cité. Viewed across vineyards, the fortress stands as if from a fairy tale. Fortified since Roman times, Carcassonne was a Cathar stronghold in the Middle Ages. In the 1800s, Viollet-le-Duc imaginatively restored the double walls and the chateau they shelter. At a time when so many of France’s monuments were being neglected, he rallied for restoration. The project took fifty years and sadly, he did not live to see its glorious completion.

Inside the fortress, crowded narrow streets are lined with souvenir stands, restaurants, and half-timbered houses. I wander past patrons dining at tables under a leafy canopy, artists painting water colours and children in crusader outfits brandishing plastic swords. Two falconers, with their beady-eyed charges gripping their leather-gloved arms, add to the medieval atmosphere. On the grass lices between the long inner and outer sheer rock walls, I stroll in relative solitude past black slate roofed towers and square cut bastions. Carcassonne is a World Heritage Site and the fortress, while impressive by day, is stunningly lit at night. As the evening sky fades to a dusky blue and the spotlights come on, the fairy tale towers and walls glow golden. I readily imagine a centurion slowly patrolling the walls.

Inside the fortress, crowded narrow streets are lined with souvenir stands, restaurants, and half-timbered houses. I wander past patrons dining at tables under a leafy canopy, artists painting water colours and children in crusader outfits brandishing plastic swords. Two falconers, with their beady-eyed charges gripping their leather-gloved arms, add to the medieval atmosphere. On the grass lices between the long inner and outer sheer rock walls, I stroll in relative solitude past black slate roofed towers and square cut bastions. Carcassonne is a World Heritage Site and the fortress, while impressive by day, is stunningly lit at night. As the evening sky fades to a dusky blue and the spotlights come on, the fairy tale towers and walls glow golden. I readily imagine a centurion slowly patrolling the walls.

If You Go:

If You Go:

It’s Remembrance Day, 2014 and I’m interlocking the sleeves of my parents’ Air Force jackets. They are arm in arm once more, laid out on the bed. Mum, a coding and deciphering officer with the RAF, and Dad, an air observer/navigator with the 10th Squadron, Bomber Command, met at a dance in Gander, Newfoundland in December, 1944. They’d both already served five long years. I salute them. Then I hug their blue-gray wool serge, touch their caps, and straighten their belts.

It’s Remembrance Day, 2014 and I’m interlocking the sleeves of my parents’ Air Force jackets. They are arm in arm once more, laid out on the bed. Mum, a coding and deciphering officer with the RAF, and Dad, an air observer/navigator with the 10th Squadron, Bomber Command, met at a dance in Gander, Newfoundland in December, 1944. They’d both already served five long years. I salute them. Then I hug their blue-gray wool serge, touch their caps, and straighten their belts.

A visit to Notre-Dame Cathedral’s Romanesque and Norman-Gothic edifice which pre-dates Mont-Saint-Michel was a must-see. It was consecrated in the fourth-century and flourished in King William’s reign. Its façade, chapter-house labyrinth, choir, as well as its fifteenth-century frescoes of angel musicians in the crypt, all captivate.

A visit to Notre-Dame Cathedral’s Romanesque and Norman-Gothic edifice which pre-dates Mont-Saint-Michel was a must-see. It was consecrated in the fourth-century and flourished in King William’s reign. Its façade, chapter-house labyrinth, choir, as well as its fifteenth-century frescoes of angel musicians in the crypt, all captivate. A yearning to be in the open air brings us to Velos Location: We rent bikes for eight hours at 16 Euros apiece and are transported to countryside where we hear the farmer’s tractor mowing hay. Or are those really tanks approaching? The trees that line the roads look mature, but aren’t they uniformly pushing the seventy years since peace was brokered? In 1944, trees provided fuel or defensive barriers on low-tide beaches, and their removal meant less shelter for an enemy. Today, those same trees flicker from shadow to light like newsreels, transmitting ticker tape noises to our spokes, and crank us forward.

A yearning to be in the open air brings us to Velos Location: We rent bikes for eight hours at 16 Euros apiece and are transported to countryside where we hear the farmer’s tractor mowing hay. Or are those really tanks approaching? The trees that line the roads look mature, but aren’t they uniformly pushing the seventy years since peace was brokered? In 1944, trees provided fuel or defensive barriers on low-tide beaches, and their removal meant less shelter for an enemy. Today, those same trees flicker from shadow to light like newsreels, transmitting ticker tape noises to our spokes, and crank us forward. We chance upon the British Cemetery of War Graves of Bazenville-Ryes en route to Juno. Among its nearly 1000 souls, it shares the high ground with British, American, Canadian and German soldiers. The only borders here are lovely weed-free plantings of roses, oregano and lavender.

We chance upon the British Cemetery of War Graves of Bazenville-Ryes en route to Juno. Among its nearly 1000 souls, it shares the high ground with British, American, Canadian and German soldiers. The only borders here are lovely weed-free plantings of roses, oregano and lavender. Longues-sur-Mer, the German Battery, still houses a 150-millimeter gun and four bunkers. Martine conducts the tour of the only battery to retain its original naval gun. These powerful long-range guns could have devastated had they functioned properly. The four guns were up, ready and firing over the 20-kilometer range, but a sand dune blocked the telescopic view for the shiny new range-finder still in its box. Without a range-finder, the guns fired blindly like big barking dogs, until direct hits silenced two of them just before the surrender.

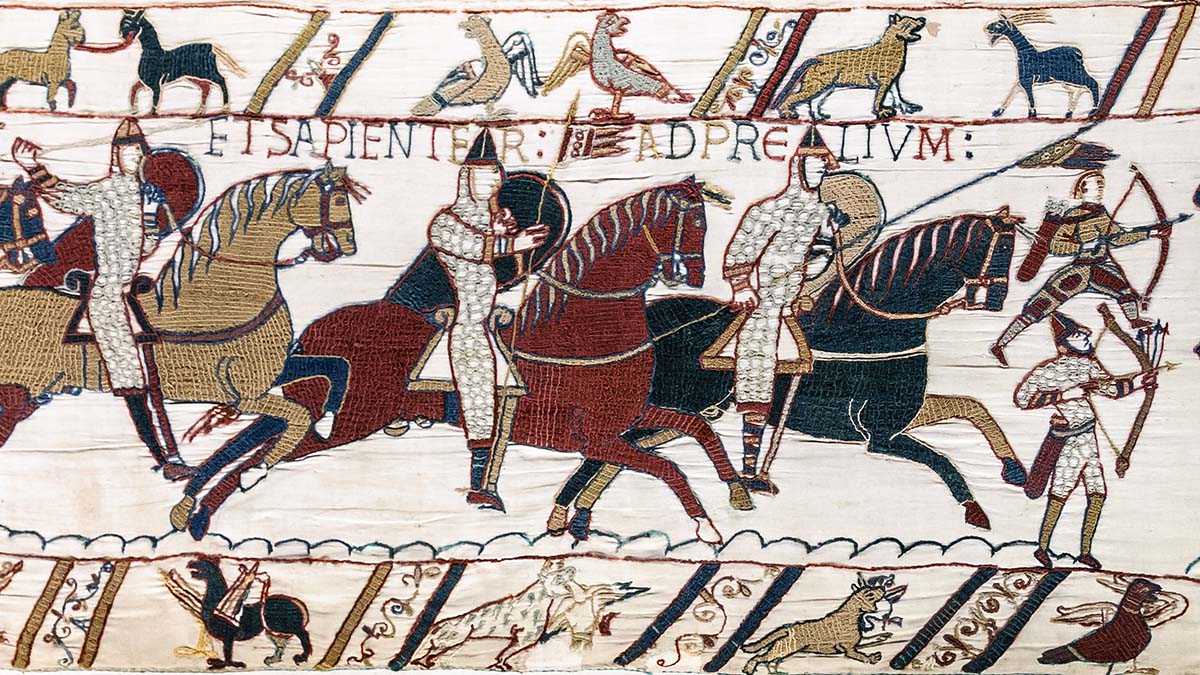

Longues-sur-Mer, the German Battery, still houses a 150-millimeter gun and four bunkers. Martine conducts the tour of the only battery to retain its original naval gun. These powerful long-range guns could have devastated had they functioned properly. The four guns were up, ready and firing over the 20-kilometer range, but a sand dune blocked the telescopic view for the shiny new range-finder still in its box. Without a range-finder, the guns fired blindly like big barking dogs, until direct hits silenced two of them just before the surrender. This summer, 2014, we visited Portsmouth’s D-Day Museum to view the recently-completed Overlord Tapestry that commemorates D-Day. I met Mary Turner Verrier, a 91-year-old Red Cross Nurse and veteran of Dieppe, Dunkirk and D-Day. Mary treated casualties of war, both civilians and servicemen, primarily for flash burns.

This summer, 2014, we visited Portsmouth’s D-Day Museum to view the recently-completed Overlord Tapestry that commemorates D-Day. I met Mary Turner Verrier, a 91-year-old Red Cross Nurse and veteran of Dieppe, Dunkirk and D-Day. Mary treated casualties of war, both civilians and servicemen, primarily for flash burns.

No one remembers its history exactly but there is some thought that the fair originated in the middle ages. In 1697 the historian Christoph Wagenseil, a native of Nuremberg, mentioned the Christkindlesmarkt in the second history of the town where he described the event much as it is celebrated today.

No one remembers its history exactly but there is some thought that the fair originated in the middle ages. In 1697 the historian Christoph Wagenseil, a native of Nuremberg, mentioned the Christkindlesmarkt in the second history of the town where he described the event much as it is celebrated today. My wife and I are visiting with relatives and enjoying the brisk air. There are golden angels hanging everywhere. This is a very popular festival in Germany and one that is also enjoyed by tourists. We pass by rows and rows of colorful booths, each filled with such holiday delights as glittering Christmas tree decorations, clever toys from Nuremberg craftsmen, marvelous Lebkuchen, a cookie usually made from honey, spices, nuts, or candied fruit, and pungent gingerbread. Then are also figurines of the Christ Child in his crib, surrounded by Mary, Joseph, and adoring shepherds. Faintly in the distance there is music and as we draw nearer we hear the sound of a children’s choir performing a variety of Christmas songs. We linger awhile to enjoy the moment and the spirit of Christmas.

My wife and I are visiting with relatives and enjoying the brisk air. There are golden angels hanging everywhere. This is a very popular festival in Germany and one that is also enjoyed by tourists. We pass by rows and rows of colorful booths, each filled with such holiday delights as glittering Christmas tree decorations, clever toys from Nuremberg craftsmen, marvelous Lebkuchen, a cookie usually made from honey, spices, nuts, or candied fruit, and pungent gingerbread. Then are also figurines of the Christ Child in his crib, surrounded by Mary, Joseph, and adoring shepherds. Faintly in the distance there is music and as we draw nearer we hear the sound of a children’s choir performing a variety of Christmas songs. We linger awhile to enjoy the moment and the spirit of Christmas. There are booths filled with such specialties as savory-smelling roasted sausages, delicately grilled herrings, and my favorites schaschlik (skewered meat usually lamb) and mulled wine. We partake of the mulled wine to help warm us in the cool winter air. There are sweets, of course, all kinds of traditional candies and all manner of cookies. The Nuremberg Christkindlsmarkt is full of wonderful sights, sounds and smells. It symbolizes for adults unforgettably beautiful childhood memories and it is little short of paradise for all age groups. However, it is also important to discover other Christmas markets in Europe.

There are booths filled with such specialties as savory-smelling roasted sausages, delicately grilled herrings, and my favorites schaschlik (skewered meat usually lamb) and mulled wine. We partake of the mulled wine to help warm us in the cool winter air. There are sweets, of course, all kinds of traditional candies and all manner of cookies. The Nuremberg Christkindlsmarkt is full of wonderful sights, sounds and smells. It symbolizes for adults unforgettably beautiful childhood memories and it is little short of paradise for all age groups. However, it is also important to discover other Christmas markets in Europe.

The

The  My wife and I and my cousin and his wife walked toward the Ljubljanica River. This year the Christmas season began on Tuesday, December 3, 2013 with the decoration of the town’s buildings and Christmas trees with lights that were switched on throughout the city. There was about 64 kilometers of lighting sculptures and light garlands installed on the trees and seven spruces located in the Preseren Trg (Market), at Figovec, in Levstikov Trg, Pod Tranco, next to the City Hall and in its Atrium as well as on the Ljubljana Castle. This was the beginning of the festive season that lasted until the December 31 New Year’s Eve celebration.

My wife and I and my cousin and his wife walked toward the Ljubljanica River. This year the Christmas season began on Tuesday, December 3, 2013 with the decoration of the town’s buildings and Christmas trees with lights that were switched on throughout the city. There was about 64 kilometers of lighting sculptures and light garlands installed on the trees and seven spruces located in the Preseren Trg (Market), at Figovec, in Levstikov Trg, Pod Tranco, next to the City Hall and in its Atrium as well as on the Ljubljana Castle. This was the beginning of the festive season that lasted until the December 31 New Year’s Eve celebration. Along the banks of the Ljubljanica River there were wooden stalls set up, decorated with Christmas ornaments and the scent of sausage; pastries, roasted chestnuts, and hot mulled wine filled the air. Vendors were also selling an assortment of unique Christmas gifts. All around us the varied colored lights begin to sparkle. The Franciscan church of the Annunciation on Preseren Square its pink façade aglow and its statuesque columns were bathed in white lights highlighting the face of the church. On the steps there was a crowd of people exiting while others patiently waited to enter the church to view the nativity scene and numerous religious displays inside.

Along the banks of the Ljubljanica River there were wooden stalls set up, decorated with Christmas ornaments and the scent of sausage; pastries, roasted chestnuts, and hot mulled wine filled the air. Vendors were also selling an assortment of unique Christmas gifts. All around us the varied colored lights begin to sparkle. The Franciscan church of the Annunciation on Preseren Square its pink façade aglow and its statuesque columns were bathed in white lights highlighting the face of the church. On the steps there was a crowd of people exiting while others patiently waited to enter the church to view the nativity scene and numerous religious displays inside. New this year to the festivities was an open-air life-size outdoor Nativity scene with a wooden manger, figures of the three Magi, shepherds, sheep and other animals all made out of straw. This was made by the Anton Kravanja Christmas Cribs Association.

New this year to the festivities was an open-air life-size outdoor Nativity scene with a wooden manger, figures of the three Magi, shepherds, sheep and other animals all made out of straw. This was made by the Anton Kravanja Christmas Cribs Association.

Recognizable to any medieval citizen, the Baptistery and Duomo remain the heart of Florence. Dante’s ‘bel San Giovanni’ is one of the city’s oldest and most famous buildings. Medieval houses still line the Piazza Duomo, many still proudly displaying a stone coat of arms. Like many Florentines of the time, Dante was baptized in the large octagonal font of the Basilica. The building itself dates back to the 4th century. The 13th century mosaics covering the ceiling show with graphic detail the horrors and glories of the Last Judgment. Dante never saw Ghiberti’s famed doors, for they would not grace the building for another century.

Recognizable to any medieval citizen, the Baptistery and Duomo remain the heart of Florence. Dante’s ‘bel San Giovanni’ is one of the city’s oldest and most famous buildings. Medieval houses still line the Piazza Duomo, many still proudly displaying a stone coat of arms. Like many Florentines of the time, Dante was baptized in the large octagonal font of the Basilica. The building itself dates back to the 4th century. The 13th century mosaics covering the ceiling show with graphic detail the horrors and glories of the Last Judgment. Dante never saw Ghiberti’s famed doors, for they would not grace the building for another century. For the hardy, 463 steps lead from the floor of the Duomo and up through a labyrinth of corridors and stairwells to the top of the cupola. (The most difficult part of the climb is over the arch; there is a spot here for lovers to place a padlock and throw away the key. In hidden corners remain marks left on the brickwork by the medieval builders.) The cupola soars to the height of the neighbouring hills. The view embraces the history of Florence, with many a medieval street following the course of their Roman precursors. Private palaces survive, and a few towers – or torre, outlawed in 1250 – still remain.

For the hardy, 463 steps lead from the floor of the Duomo and up through a labyrinth of corridors and stairwells to the top of the cupola. (The most difficult part of the climb is over the arch; there is a spot here for lovers to place a padlock and throw away the key. In hidden corners remain marks left on the brickwork by the medieval builders.) The cupola soars to the height of the neighbouring hills. The view embraces the history of Florence, with many a medieval street following the course of their Roman precursors. Private palaces survive, and a few towers – or torre, outlawed in 1250 – still remain. Dominating the Palazzo Vecchio, the Piazza della Signora has continued as the centre of political activity since the Middle Ages. Heavy traffic has been banned since 1385. The imposing façade of the Palazzo Vecchio has remained virtually unchanged since it was built (1299 – 1302) – Dante writes of how the houses of the Ghibelline Uberti were demolished after the triumph of the Guelfs, and the new Palazzo built on their ruins. (The Piazza della Signora is itself built over Roman ruins.)

Dominating the Palazzo Vecchio, the Piazza della Signora has continued as the centre of political activity since the Middle Ages. Heavy traffic has been banned since 1385. The imposing façade of the Palazzo Vecchio has remained virtually unchanged since it was built (1299 – 1302) – Dante writes of how the houses of the Ghibelline Uberti were demolished after the triumph of the Guelfs, and the new Palazzo built on their ruins. (The Piazza della Signora is itself built over Roman ruins.) Walking beneath the arch into the Via Santa Margherita leads past the 12th century Santa Margherita de’ Cerchi, where the poet married Gemma Donati (they were betrothed when Dante was nine). It is also where he first saw Beatrice Portinari, the woman he immortalized in his writing. Beatrice’s father, Folco Portinari, is buried here.

Walking beneath the arch into the Via Santa Margherita leads past the 12th century Santa Margherita de’ Cerchi, where the poet married Gemma Donati (they were betrothed when Dante was nine). It is also where he first saw Beatrice Portinari, the woman he immortalized in his writing. Beatrice’s father, Folco Portinari, is buried here.

Standing near the site of the original Roman crossing of the Arno, this was the city’s only bridge until 1218. In Dante’s time the Ponte Vecchio was home to butchers and grocers; since the 16th C it had been the place to shop Florence’s most spectacular jewellery.

Standing near the site of the original Roman crossing of the Arno, this was the city’s only bridge until 1218. In Dante’s time the Ponte Vecchio was home to butchers and grocers; since the 16th C it had been the place to shop Florence’s most spectacular jewellery. On the left of the church runs the Costa di San Giorgio; Galileo once lived at No 9. At the end of the road stands the Porta San Giorgio, the oldest of the surviving city gates (Florence was still a wall city in Dante’s time.) A steep walk away is perhaps the most unspoilt of all the Romanesque churches in Tuscany: San Miniato al Monte. It’s classical façade of green-grey and white marble has looked down over Florence since 1018.

On the left of the church runs the Costa di San Giorgio; Galileo once lived at No 9. At the end of the road stands the Porta San Giorgio, the oldest of the surviving city gates (Florence was still a wall city in Dante’s time.) A steep walk away is perhaps the most unspoilt of all the Romanesque churches in Tuscany: San Miniato al Monte. It’s classical façade of green-grey and white marble has looked down over Florence since 1018.