by Andrea Kirkby

Some cities have grown continuously through the ages. They’re like onions, layer on layer of skin which you can unpeel all the way back to the foundations. Rome is like that, for instance, or Venice. But London was scarred forever by one single disruptive event – the Great Fire which laid the city waste in 1666. It’s a city whose history began again with Sir Christopher Wren, a city which lost its past.

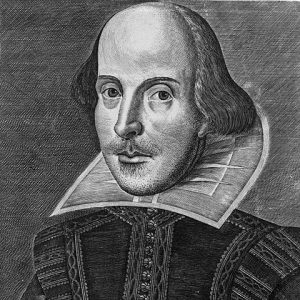

So if you want to see the London that Shakespeare knew, the London where John Harvard grew up, you’ll have to look hard. But it can be found – if you try hard enough.

So if you want to see the London that Shakespeare knew, the London where John Harvard grew up, you’ll have to look hard. But it can be found – if you try hard enough.

Of course Shakespeare would have known the older medieval buildings of London – the Tower, for instance, and Westminster Abbey. But his London was one in which the great monasteries had disappeared a generation ago, and their buildings had all been privatised – sold off to nobles and gentry, sometimes for use as houses, sometimes just as quarries for building materials.

The City, in particular, was thriving, as London became a great trading centre dominated by an oligopoly of wealthy merchants. There’s almost nothing left in the City itself of Shakespeare’s London – this was where the Great Fire started, and burned most fiercely – but if you head out along Fleet Street or High Holborn towards the Inns of Court, you’ll find a few gems of Elizabethan and Jacobean architecture.

Near Chancery Lane tube station, for instance, you can find Staples Inn – a marvelous, long range of fine half timber with huge gables facing the street, and a peaceful little courtyard tucked behind. This was one of the Inns of Court in Shakespeare’s day – the Inns were later reduced to just the four that now exist. The vast majority of buildings in Shakespeare’s London were wooden, like Staples Inn – one reason that the Fire was able to take hold so quickly. Yet wooden buildings didn’t have to be humble or unpretentious – this building shows the immense size that half timber work could achieve, and it’s mightily impressive.

Visit the Victoria & Albert museum and you’ll find an even greater work of half timber – the façade of Sir Paul Pindar’s house from Bishopsgate, in the City, dated about 1600. With its fine oriel windows, expansive glazing, and rich carving, it’s a testament to Pindar’s taste and wealth – he had made a fortune trading with Venice, and was later England’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Imagine a street full of such house fronts and you’ve got an idea of what the richer areas of the City would have looked like at the time.

Visit the Victoria & Albert museum and you’ll find an even greater work of half timber – the façade of Sir Paul Pindar’s house from Bishopsgate, in the City, dated about 1600. With its fine oriel windows, expansive glazing, and rich carving, it’s a testament to Pindar’s taste and wealth – he had made a fortune trading with Venice, and was later England’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Imagine a street full of such house fronts and you’ve got an idea of what the richer areas of the City would have looked like at the time.

Another Jacobean house stands at number 17 Fleet Street, by the entrance to the Temple. This fine half timber building was erected in 1610, as a tavern, originally known as ‘The Prince’s Arms’. The way the first floor is jettied out over the street, and the projecting oriel windows, are typical of seventeenth century vernacular architecture. But the house’s real treasure is inside – Prince Henry’s Room, which contains a fine plasterwork ceiling with the three feathers of the Prince of Wales set into a fine geometrical framework.

The name commemorates the investiture of Henry, James I’s oldest son, as Prince of Wales. Had Henry lived to become Henry the Ninth, who knows how English history might have developed – Charles I would never had come to the throne, and there might never have been a Civil War; Oliver Cromwell might have remained a local worthy in Huntingdonshire and never got involved in politics. But Henry died at just eighteen.

The Middle and Inner Temple were not just centres for lawyers’ training in Shakespeare’s day – they were centres of literary culture. The poet John Donne studied here, masques by Middleton and Beaumont were performed here, and Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night was first performed at Middle Temple Hall. Although the Temples are still working environments, occupied by barristers’ chambers, the grounds are open to visitors – like Staples Inn, another oasis of calm in the middle of bustling London.

The Middle and Inner Temple were not just centres for lawyers’ training in Shakespeare’s day – they were centres of literary culture. The poet John Donne studied here, masques by Middleton and Beaumont were performed here, and Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night was first performed at Middle Temple Hall. Although the Temples are still working environments, occupied by barristers’ chambers, the grounds are open to visitors – like Staples Inn, another oasis of calm in the middle of bustling London.

In Shakespeare’s day, the City was the preserve of trade and commerce, while Westminster was a separate urban area, the seat of the court and of government. Both the City and Westminster were tightly regulated. So to see Shakespeare’s real home, we’ll need to go south of the river, to Southwark – which as it didn’t come under City rules and regulations, but under the personal rule of the Bishop of Winchester, became a free enterprise culture. Here were the coaching inns at the start of the main road south to Kent; here were taverns, and also brothels, bear baiting, bathhouses, and theatres. This was where City apprentices escaped to on their infrequent days off, and courtiers went slumming.

And here you’ll find the Globe Theatre. Not Shakespeare’s original – that stood on a site a few hundred yards away, in Park Street – but a reconstruction, that still hosts plays in the summer. There’s a museum you can visit, but I find it a bit disappointing. The right way to experience the Globe is the way Shakespeare’s audience did – to come to a play here. And if you want to, you can be a ‘groundling’ – standing up throughout the performance in the open centre of the auditorium; though if it rains, you may be in for a soaking.

Shakespeare Walking Tour in London

If You Go:

www.elizabethan.org/compendium/27.html – Map and history of Tudor London

www.shakespeares-globe.org

Image credits:

London tower bridge by: Diliff / CC BY-SA

William Shakespeare portrait: Martin Droeshout / Public domain

Sir Paul Pindar’s house: Henry Dixon / Public domain

Middle Temple Hall: Diliff / CC BY-SA

About the author:

Andrea Kirkby is the founder of Podtours, a company which provides downloadable audio tours of European destinations. She is also a travel writer and photographer. The Podtour of Shakespeare’s Southwark takes you through Elizabethan theatre land and can be downloaded from www.podtours.co.uk/Southwark-podtour.htm.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.