The Star-Crossed Shangri-La

by Rick Neal

After a tortuous bus ride through the Guatemalan highlands, I’ve finally arrived at the village of Nebaj. The tranquil scene before me is quite a contrast after spending the last four hours being squashed like a cold anchovy. A cobblestone street is lined with white, adobe buildings, streaks of rain visible against their red, tiled roofs. The damp air smells of pine needles. Down the road a quiet plaza fronts a colonial church. Panoramic, mist-shrouded peaks barely visible in the distance resemble the coast mountains of western Canada.

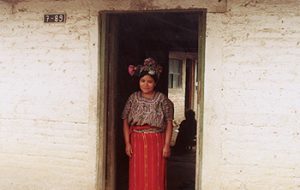

A few women with dusky skin and thick, Mayan lips chatter in the plaza as they sell vegetables spread over linen cloths. They wear blouses with green, yellow, red, and orange geometric patterns over dazzling, crimson skirts. Their raven hair is adorned in braided strips of cloth with red and green pompoms.

A few women with dusky skin and thick, Mayan lips chatter in the plaza as they sell vegetables spread over linen cloths. They wear blouses with green, yellow, red, and orange geometric patterns over dazzling, crimson skirts. Their raven hair is adorned in braided strips of cloth with red and green pompoms.

Located in the Cuchamatanes Mountains, Nebaj is the largest of three towns that make up Guatemala’s Ixil Triangle, one of the smallest ethnic regions in Central America and the only place in the world where the Ixil language is spoken. Few tourists venture to this isolated area, though it offers spectacular scenery and colourful Mayan culture.

Other than the women in the plaza and a handful of children on the street, there are few villagers in sight. A gap-toothed man leading a mule raises a hand to his cowboy hat as he passes me. He is the only adult male in sight. I had read of an uprising here in the 1980s, when the army had executed much of the male population.

A stout Ixil woman with coal-black eyes approaches. In spite of the rain and the cool temperature she is in bare feet.

A stout Ixil woman with coal-black eyes approaches. In spite of the rain and the cool temperature she is in bare feet.

“Want buy weavings, Senor?” she inquires in Spanish.

“Not now,” I answer. “Maybe later. First I want a hotel. You have a shop?”

“No shop,” she says. “You come my home, not far.” Her Spanish isn’t much better than my own. We agree to meet in an hour in front of a hotel down the road that she says is the best in town. She tells me her name is Magdalena.

The hotel room is cell-like, and the 24 hora agua caliente promised by the desk clerk is a fiction, but at seven dollars a night I can’t complain.

An hour later Magdalena is waiting outside as promised. I follow her in the rain down a pebble road to a one-room, dirt floor adobe building. A wobbly table and chairs and two rickety beds are the only furniture. She shows me a tiny courtyard in the back, where several boisterous chickens and a scrawny turkey run freely. Two, fat jade-green parrots perch on a stand, while a Mayan woman in the corner weaves on a backstrap loom.

Taped to the wall is a faded photo of a young guy in military fatigues. “Your husband?” I ask.

“No, my brother. He was taken years ago by army. My husband leave many months ago.” She bites her lower lip and shrugs. “Life is hard, but… what can I do?” She says this matter-of-factly, without a trace of self-pity.

She opens two large bags and spreads dozens of hand-made weavings across the beds: table runners, wall hangings, crocheted handbags, and thick, woolen blouses in a myriad of sizes and colours. Some of the patterns look similar to the blouse she is wearing, while others are markedly different. Many have embroidered figures of birds and animals.

“You made these?” I ask.

“No,” she says. “I make some, but most by other women. Some live far. They give to me to sell because I live close to center town.” She indicates a piece of paper attached to the back of each with the name of its creator.

I purchase four table runners with red, green, and brown bird figures, a stunning blue and green bag, and a gorgeous wall hanging. I consider acquiring an extra weaving, but as my cash is running low I decide against it. Magdalena wraps the money tightly around her fingers, as if she fears it will vanish. Her take today has been about forty dollars, a considerable sum in the poorest area of this impoverished country.

I purchase four table runners with red, green, and brown bird figures, a stunning blue and green bag, and a gorgeous wall hanging. I consider acquiring an extra weaving, but as my cash is running low I decide against it. Magdalena wraps the money tightly around her fingers, as if she fears it will vanish. Her take today has been about forty dollars, a considerable sum in the poorest area of this impoverished country.

Later, I set out in search of some dinner. The rain has finally stopped; the wet cobblestone streets shimmer in the late afternoon sun. The Mayan women are now packing their unsold vegetables. A couple of older men in white shirts play cards in the plaza, while a few teenage girls giggle on the church steps. Each person I meet greets me with a sincere buenas tardes.

Down a lane I come upon the “Maya Inca” restaurant. The cozy place has only a few wooden tables and chairs, but it looks clean enough and has, unlike the grubby comedor across from my hotel, an actual wood floor.

The owner is Peruvian-born Alberto Heredia, an amiable man who speaks decent English. He tells me that he moved to Nebaj several years ago, married an Ixil woman, and together they opened this restaurant. On his recommendation, I order chicken with pear sauce, a delicious Peruvian specialty.

After dinner, he brings coffee and sweet pastries and, since the two other customers have left, he accepts my invitation and joins me for dessert.

“I enjoy meeting people from outside,” he explains. “For years no foreigners came, because of the problems. Maybe you know? Now a few are coming, but we need more, to help the economy.”

“I read that the army came in the 1980s looking for insurgents, that they killed a lot of people. Is that true?”

He draws a deep breath. “There were some rebels, but the army also killed many innocent people. Many men were forced to join the army and fight their own people.” I’m reminded of Magdalena’s brother. “They destroyed two dozen villages.” He pauses to collect himself. The memories are obviously painful “In one town they put all the men in a church and shot them. They even destroyed animals, their food source. Thousands were killed. Many fled to Mexico.”

“And now?” I ask. “Didn’t the government and the rebels recently sign a peace treaty?.”

“Yes,” he answers. “A year ago, but many still have not returned. And it will take years to rebuild their villages.” He lowers his coffee cup. “These are incredibly kind, and strong people. They want only to live their lives in peace and be left alone, but for 500 years their rights have been ignored. They are… I can’t remember the English word…in Spanish, traumatismo.”

“Traumatized,” I answer.

“Yes,” he nods. “It is very sad, my friend.”

On the stroll back to my hotel, for the first time I understand the sadness in the eyes of the people I pass.

The next morning, I wake to the sounds of birds chirping. Since my bus doesn’t depart until the afternoon, I decide to take advantage of the fine weather and explore some of the countryside.

I walk along a dirt road toward the neighbouring hamlet of Chajul, crossing a bridge that leads to a path along a narrow river lined with tin-roofed houses and small gardens. A farmer working his crops removes his hat and waves. Burros are tied to fences along the road. Palm trees, giant pines, and alders wrapped in lush orchids surround me. Laughing children appear from behind hedges, only to vanish if I venture too close.

Stopping beside a small waterfall, I reflect on my time here. Over the last two days I’ve developed a great respect for the resilient Ixil people. How they’ve remained so humble and friendly after all they’ve experienced, indeed how they’ve survived at all, is astonishing. This place must have been a Shangri-La at one time. As I fall asleep next to the waterfall, I pray that soon it will be again.

I wake with a start, realizing that my bus leaves in less than an hour.

Back at the hotel, I’m frantically stuffing dirty socks into my pack when I hear a knock.

Magdalena stands in the doorway with her arms folded, her gaze fixed on the ground. She is wearing the same outfit as yesterday, except for a weaving draped across her shoulder.

I’m taken aback to see her. “Hola,” I manage.

“Hola,” she answers. Blushing, she takes the weaving from her shoulder and places it in my hand. She bows quickly and is gone. I stare down at the weaving. It’s the one I had wanted to buy yesterday. A single word is scribbled on a label: Magdalena.

Lake Atitlan Village Tour from Panajachel

If You Go:

GETTING THERE:

Nebaj can only be accessed by bus from one of two nearby towns: Santa Cruz del Quiche (2.5 hrs. US $3) or Sacapulas (1.5 hrs. US $1) Reportedly, the road has recently been paved.

HOTELS AND RESTAURANTS:

For such a remote destination, Nebaj has a good selection of accommodations and places to eat, all within a couple blocks of the main square. Many have internet access. It is also possible to arrange a home stay with a local family.

Hostel Media Luna Media Sol (www.nebaj.com/hostel.htm 502-5749-7450 US $5-6) An ideal budget option, this hostel offers two dormitories, private rooms, a kitchenette, a traditional Mayan steam bath, and even a Spanish school on the roof.

Hotel Turansa (502-7755-8219) US $9/$16/$18) Clean, comfortable rooms offer private baths, hot water and cable TV.

Popi’s Restaurant This newer eatery offers a variety of local specialties, as well as a few American dishes. A percentage of the profits goes to help local Mayan children.

Adventure tourism in Guatemala

About the author:

Rick Neal is a freelance writer living in Vancouver, Canada. Apart from Central America, he has travelled to Mexico, Europe, and Southeast Asia. He hopes to make South America his next destination. Rick has been published in offbeattravel.com and www.hackwriters.com.

Photo Credits:

Nebaj Calle y Iglacia by g.bertschinger under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Central Plaza of Santa Maria Nebaj by Rrenner under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 License.

Guatemala weaving by Hubertl / CC BY-SA

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.