by Georges Fery

by Georges Fery

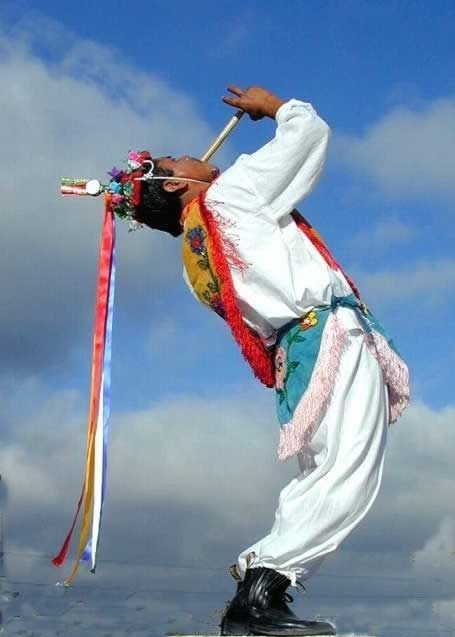

On the morning of the first ceremony, the musician climbed up the pole and stood on top of the capstan playing the “tunes of the east, west, north and south” (Sones del oriente, poniente, norte y sur). Once back on the ground, the k’ohal followed by the flyers climbed up the pole at the sound of the “ascent tune” (Son del ascenso). At that time, they were symbolically identified as the red headed woodpecker climbing a tree trunk, for the flyers red headdress mimicked that of the bird, ritually second only to the eagle. Once on top of the pole they alternately stood and danced on the capstan calling to the deities, starting with the east where life is believed to have come together with sunrise, followed by the north, west, and south. The k’ohal then followed flapping large bird feather wings in his hands, while blowing a bird-bone whistle sounding like the high-pitched cry of a bird of prey. He then sat on the capstan while the musician played the ”tune of the east” (Son del oriente). Then the k’ohal stood again on the capstan and, while holding a bottle of strong liquor (aguar diente) in his right hand filled his mouth and, as a salute, forcefully blew the liquid toward the gods of each cardinal directions associated with their constituents: earth, air, fire, and water. Then, bending fully backward, he played the “tune of the center of the earth” (Son del medio de la tierra), his flute facing the sun while dancing on the capstan.

The musician on the ground then played the “Huasanga tune” (Son de la Huasanga), a happy popular Huastec song and dance with his flute and small drum on which were painted two stars, a nine rays star for sunrise and a seven rays star for sunset. After the last note, the k’ohal gave the signal of the dance to his team by playing the “tune of flight” (Son de la volada). At that time, the four dancers seating on the crosspiece below the capstan, fell backward toward the ground, each tied at the waist to a rope knotted on their belly.

As the capstan rotated the ropes unwound counterclockwise in a widening circle, creating a moving pyramidal shape. The dancers held by the rope started their fall heads up, but quickly shifted upside down. To keep their inverse position, they held the thick rope above them between the big and index toes of either foot. They then spread out their arms and, at times, held eagle or other large bird feathers in their hands while blowing a small bird-bone whistle with a high-pitched sound. Then the k’ohal on top of the pole played the “tune of flight” (Son de la volada), followed by the musician on the ground playing the “flyer’s tune” (Son del volador), which was repeated four times for each of the four flyers, followed by the “fall’s tune” (Son del descenso). The ropes unraveled under the flyers’ collective weight and speed as the capstan turned and the ropes tensed circling the pole thirteen times, or one set of thirteen circle for each flyer (13×4), for a total of fifty-two, the number of years of the “century” of Mesoamerican culture’s past.

When the flyers reached a few feet above the ground an experienced team member loudly called them to lose the rope held by their toes and turn their body back up; they then landed running. As his team “flew,” the k’ohal, as the fifth sun, danced on the narrow capstan alternately facing the deities of the four quarters.

When the four team members were safely on the ground, he used one of the ropes to slide down. Then the musician played the “tune to untie” (Son del desamare) for the team to unbind their ropes, followed by the k’ohal who played the “farewell tune” (Son de la despedida). After each flight a new team climbed up to the capstan and carefully rolled the ropes back up around the pole for their flight.

Ceremonies also took place at night. Those in Tameleton started at midday and continued throughout the night ending the following mid-day. During nighttime ceremonies, there were rituals marking twilight, associated with “beginning” or birth, and dawn associated with end, death or “goodbye” to Huastec and Totonac traditions. We know that rituals are integral to complementary opposites and their respective deities related to day and night. We may, however, safely assume that some nighttime rituals were associated with select deities of the night and, perhaps, with those of darkness.On a ritual standpoint, one may ask why each step of a ceremony was accompanied with repeated flute and drum sounds. It was then believed that while words from descendants were heard by their ancestors, they were not heard by gods or deities who could not understand the spoken word. To call their attention, therefore, chants or musical sounds, constant drumbeats, repeated two-tone atonements, prayers sung alone or in unison, were the only means to carry human appeals. We remember that the k’ohal called the attention of the deities of the four quarters and those of the Sun with his whistle, and so did the musician’s repeated tunes with both his whistle and mini drum at each phase of the ceremonies.

Stresser-Péan reports that all dancers observed hallowed rules that varied among ethnic groups. Two rules, however, were strictly observed by all: fasting, which may vary according to cultures from nine or more days before the event. At the end of each day, supper would take place with team members, their shaman, ritual orator and musician.

The second, sexual abstinence during the fasting period and the week’s rituals, was strictly observed by all, for its violation was associated with the worst possible outcome, the fall and death of a team member. Of note is that the victim was not directly associated with the infraction, for it might have been committed by any of the group members.

When a dancer died from a fall, his soul the Huastecs believed, transformed into an eagle, for the words soul and birds are synonimous in their language. It may be the reason why the ritual was called “the eagles dance” (Danza de las águilas) by the Huastecs and “the flyers dance” (Danza de los voladores) by the Totonacs. For both group and others at the time, the dance was a religious ritual that, under coercion from the Europeans in late 16th century, was desacralized.

Clothing and adornments, like words and sounds, are integral to creeds and their rituals. Among historic references to the dancers’ clothing, Dominican friar Diego Duran, who was fluent in the Nahuatl language, wrote in the Book of the Gods and Rites (1574-1576) that the flyers dressed “like eagles or other birds…” Stresser Péan point to the Codex Fernández-Leal which refers to flyers who “wore a red- feathered cone-shaped hat, like that of a bird’s head with a beak” like a woodpecker, similar to the Huastec ceremonial headgear today.

In the Huastec language the words soul and bird are synonymous. When speaking of an individual’s soul it is referred as “its bird.”

Interestingly, a k’ohal was called a “lady (or mother) eagle” for in Huastec, there is no distinction in gender designation. Dancers of recent times do not always follow traditional dress codes. In most cultures of the past and today, the dancers wore a colorful triangular hand-woven shawl artistically adorned with flowers and birds on a red background. It was worn diagonally, its apex tied to the right shoulder, while the lower part was tied to their apron belt’s left side. The red color is associated with the cardinal bird called “sun’s soul.” Over the shawl, Totonac k’ohals wore a long light blue scarf knotted below the left arm crosswise, the color of the first light of dawn before sunrise.

The day following the last ritual the pole stayed in place with its accessories. Before they left, team members tied up the four main ropes ten feet above the ground where they remained untouched for nine days. The morning of the tenth day, the musician climbed and stood up on the capstan and played several tunes closing with the “farewell tune” (Son de la despedida). Then a team of retired dancers climbed up the pole and removed the crosspiece, the capstan, and all the ropes. The stripped pole, however, will remain standing for another nine days before being ceremonially “uprooted” by pulling it down its top pointing to sunrise, all the while the musician played again the “farewell tune.” The pole was then moved to a garden or field where it was left, never to be used for another ceremony or purpose, nor its wood chopped, burned, or wasted. The pole was left in the open as a return to nature where it came from, and it was now up to nature to destroy it through time and decay. Culture could not interfere with nature’s undoing its creation, for the pole’s cultural function, came to an end.

Like the pole at the end of the ceremonies, each dancer, the musician, and the orator went through ritual cleansing, which took place near a fast-moving stream on the village’s outskirts, and a small cave or sanctuary nearby. The shaman selected five small young limbs of green foliage plants associated with medical and ritual properties. Together with burning copal powder, the plants were used to spiritually cleanse each dancer, the k’ohal and the musician. One of the plants (tokob apestoso) produced a malodorous smoke and was used against spell casters, while another (tok te), protected people from ghosts. The most potent plant for ritual cleansing was used for abortion (tokob santo). Holding a handful of limbs in his right hand, the shaman prayed in a monotonous two-tone singsong. With copal incense smoke he started to clean each man’s soul of malevolent influences that may have attempted to interfere during rituals. For each dancer and the musician, the shaman invoked the deities of the night while starting its blessings from the back of the head down to the heels, then invoking those of the light, from the feet up to the face and ears, ending on top of the head.

All the while copal smoke shrouded both team members and shaman. Once all participants were cleansed, and while still invoking deities in a low tone singsong, the shaman left each handful of used plants, now filled with hostile forces in a small rocky crevice nearby, sprinkling them with aguardiente to prohibit their escape. As we have seen, the complexity of rituals and their repetition, as in any belief structure, create an autonomous and self-sustaining universe of cause and effect that trumps reality. After the last ceremonies the flyers and their teams held an informal dinner together with their mothers, sisters, and spouses who, through week long day and night ceremonies, lived in fear of their loved one’s fall. Upon departing to their homes after the meal, the musician played the last “farewell tune” (Son de la despedida).

This is the second of a two part article about the Pole Dancers of Veracruz.

See Part One Here.

References – Further Reading:

- Guy Stresser-Pean, 2016 – La Danza del Volador Entre los Indios de Mexico y America Central

- Christian Duverger, 2007 – El Primer Mestizaje

- Anthony F. Aveni & J.K. Jackson, 2023 – Aztec Myths and Legends

- Nigel Davies, 1977 – The Toltecs

- Diego Durán, 1880 – Historia de la Indias de Nueva-España y de Tierra Firme

- Joseph W. Whitecotton, 1966 – The Zapotecs

- Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, 1905 – Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España – Códices Matritenses en Lengua Nahuatl

- Erna Fergusson, 1936 – Los Voladores

- Francisco Clavijero, 1853 – Historia Antigua de Mexico

- Raoul d’Harcourt, 1958 – Le Flûtiste-tambourinaire en Amérique

About the author:

Freelance writer, researcher, and photographer, addresses topics, from history, culture, and beliefs to daily living of ancient and today’s communities of the Americas. His articles are published online at travelthruhistory.com, ancient-origins.net and popular-archaeology.com, in the quarterly magazine Ancient American (ancientamerican.com), as well as in the U.K. at mexicolore.co.uk. The author is a fellow of the Institute of Maya Studies instituteofmayastudies.org Miami, FL and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org. As well as member in good standing of the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org, the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org, the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. americanindian.si.edu, and the NFAA – Non-Fiction Authors Association nonfictionauthrosassociation.com.

Contact: Georges Fery – 5200 Keller Springs Road, Apt. 1511, Dallas, Texas 75248 (786) 501 9692 – gfery.43@gmail.com and www.georgefery.com

Photo credits:

The Dancers Flight by @culturetrip.com

Calling the Deities by @josephordaz.com

Dancers’ Ritual Dress by @andzelaoecite.com

The Last Dance by @deliahernandezintrospecciones.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.