by George Fery

Caves are central to world cultures, used by humans from the dawn of time. They are associated with powerful natural forces believed to be the dwelling places of benevolent and malevolent deities, protectors and disruptors of communities, families and individuals’ lives.

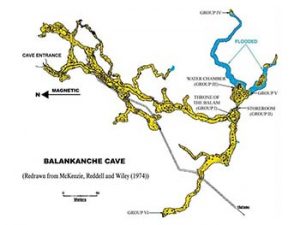

The Balankanchè cave is located 2.5mi/3.9Km southwest of Chichén Itzà’s archaeological site, near the town of Pistè. Its proximity to this major pre-Columbian site underlines the fact that Balankanchè was an integral part of Chichén Itzà for religious rituals and ceremonies.

The cave was called the “Throne of the Tiger Priest” by E. Willis Andrews, in his 1970 archaeological field report. Among known caves in the Maya lowlands, Balankanchè has received less attention than it deserves. Its significance can fully be understood in contrast to the monumental secular site above ground. The interaction between the surface elements and those of the cave, give us an unusual light on the life of the ancient metropolis.

The Itzaes were Maya-Chontales or Putunes that controlled the trade routes around the Yucatán peninsula. They occupied the island of Cozumel and from there, crossed over to the peninsula reaching Chichén Itzá in 918AD. A second group of migrant-soldiers, mixed with nahualtl speaking Toltecs, reached Chichén around 987AD, introducing the cult to Quetzalcoatl from Tula (Hidalgo). They established a military dynasty that ruled the northern peninsula (Thompson (1954, 1966, 1970), R. Piña Chán (1980). The record is in agreement with the book Chilam Balam of Chumayel that refers to two groups of invaders as the “little descent” (918AD) and the “big descent” (987AD).

A recently discovered a cenote (sink hole) 15ft/4.6m below the base of Kukulcán pyramid (aka El Castillo), called the Balamkú cave, will shed new light on beliefs and rituals of the Toltec period. The shrine, like Balankanchè, was dedicated to the Toltec religious figure Quetzalcoatl, the Mayas called Kukulcán.

The Toltec invaders, from the central plateau of Mexico and their history at Chichèn, spans from the Late to the Terminal Classic (987-1250AD). Its large Sacred Cenote, aka Well of Sacrifice, located at the end of the 600ft /180m sacbe or “white road”, the link to the Kukulcán pyramid, was believed to be the main gateway to the underworld and Cha’ak’s home from pre-Toltec times. This cenote was strictly dedicated to religious rituals and ceremonies involving human sacrifice, as remains found testify. The Xtoloc (iguana) in the city, among other cenotes in the vicinity, supplied water to the community. Of note however, is that all cenotes were at times used for religious rituals.

Balankanchè’s importance was first noted in 1958 by Josè Humberto Gómez who had explored the cave over ten years. He eventually discovered what seemed to be a false section of one of the walls. On examination, he realized it was made of crude masonry sealed with mortar covering a small access chamber. Previous archaeological expeditions had come within feet of the wall, probably sealed during the later part of Toltec occupation, not realizing what lay beyond.

Entering the chambers in 1959, researchers found a large number of ceremonial ceramics, beyond two crude stone walls 98.5ft/30m and 361ft/110m respectively from the entrance, and carved limestone effigy censers, as well as mini-metates (grinding stones) set into cavities in the cave’s complex stalagmitic formation, as well as simply laid on the floor. They were among many similar artifacts found in the cave.

Archaeologists believe that Balankanchè’s “first tenant” was probably Cha’ak, a Maya agrarian deity with mythological attributes akin to Tlaloc, the Lord of the Third Sun in Toltec mythology, whose roots go back to Teotihuacàn and, farther in time, to Olmec cosmology.

The Toltec invasion from central Mexico (987AD), explains the presence of Tlaloc ceramics and Xipe Totec, the enigmatic life-death-rebirth deity carved limestone censers, the only artifacts found in the cave. The total eradication of Cha’ak representations, underline the proscription of the old god by the new one. The Toltec invaders settled in power centers and towns, while traditional Maya-Yucatec’s Cha’ak and deities remained unchanged in the countryside. Balankanchè “second tenant” would be Tlaloc, the Toltec goggle-eye deity of rain, storm, lightning and thunder. The deity that came from Tula on the central plateau of Mexico, is associated with caves, cenotes, springs and mountain tops—all believed to be guardians and holders of rain and maize, in past and present Mesoamerican mythologies.

Tlaloc and Xipe Totec censers found in the cave are made of ceramic and limestone respectively. They represent deities that reached the Yucatán peninsula with the Toltec invaders. While relatively little is known about pre-Toltec deities and fertility gods of the Yucatán, the record indicate that the cave may have been the focus of a folk cult (Edward B. Kurjack, 2006 – personal communication).

Tlaloc and Xipe Totec censers found in the cave are made of ceramic and limestone respectively. They represent deities that reached the Yucatán peninsula with the Toltec invaders. While relatively little is known about pre-Toltec deities and fertility gods of the Yucatán, the record indicate that the cave may have been the focus of a folk cult (Edward B. Kurjack, 2006 – personal communication).

Balankanchè’s surface mounds and other structural remains are seen scattered on the site above ground. The cave entrance, in the center of the complex, was surrounded by a 115 ft/35mt circular tulum or defensive wall, 12ft/4m wide at the base and raised 4ft/1.3m above the rock base. It was surmounted by a 6ft/2m enclosure made of perishable material that is now lost to time. The reason for such a strong defensive wall is not known and may pre-date Toltec’s arrival.

The entrance today is located at the center of the circular walled area. It may not have been the location of the original entrance, nor the only access. From ground level, steps take the modern visitor down to a depth of 30ft/9m, then the corridor branches off.

The accessible part of the cave is made up of more than a mile of passageways that vary considerably in shape and size, from broad and flat (as much as 30ft/9m wide and 15ft/5m high), to narrow crawling spaces. Other passageways are no longer passable. The cave is divided into six groups, one of them, now closed may have been the other ancient access to the cave.

The accessible part of the cave is made up of more than a mile of passageways that vary considerably in shape and size, from broad and flat (as much as 30ft/9m wide and 15ft/5m high), to narrow crawling spaces. Other passageways are no longer passable. The cave is divided into six groups, one of them, now closed may have been the other ancient access to the cave.

The corridors and steps for visitors are well built, lit, maintained, and easily walkable, but there are limitations to admission to the cave. For lack of limited ventilation in the corridors, senior persons, health conditions (pulmonary and coronary in particular), or physical impediment may be prohibited entrance. Sections of the main corridors cannot be visited; some reach the water table at 70ft/22m beneath the surface in at least four places. Water depth vary with seasonal rains and entrance to the cave is sometimes suspended after sudden downpours. There is another corridor under the main one, half submerged and very difficult of access, but for professional cave archaeologists.

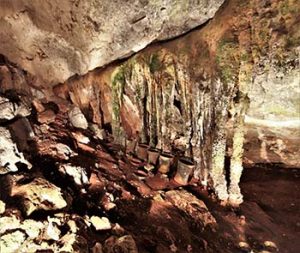

The cave’s main chamber is Group.I, a huge and impressive circular room with thousands of stalactites covering the ceiling. The floor, naturally raised as a mound, holds massive twin limestone columns made of both stalactites and stalagmites linked at the center, in the shape of a massive tree trunk.

The cave’s main chamber is Group.I, a huge and impressive circular room with thousands of stalactites covering the ceiling. The floor, naturally raised as a mound, holds massive twin limestone columns made of both stalactites and stalagmites linked at the center, in the shape of a massive tree trunk.

The cave is a strikingly beautiful work of nature; the high place of a culture that consigned its myths and beliefs in its gods and deities to the mineral world. The central column is a reminder of the trunk of the Ceiba, the mythological Wakah Chan, the “Tree of Life” whose branches reach to the heavens, while its roots are sunk deep into the underworld. The veneration of the “Altar of the Tiger Priest”, can only be understood in the context of the vision of a dual perception of life.

This impressive sanctuary created by nature but conceived by man as an altar for the gods was walled toward the end of the Terminal Classic phase (850-1000AD) The ceramics on the “altar” are representatives of two non-Maya deities from the central plateau of Mexico. Twentynine large Tlaloc-effigy biconical censers and Xipe Totec carved limestone censers were found on the mound of the altar, together with mini-metates (stone grinders) and manos, miniature ceramic plates, bowls and other offerings, dated from the Florescent (625-800AD) to the Modified Florescent (800-950AD) phases. Female Maya deities, Chak’Chel and Ix’Chel, patrons of childbirth, sexuality and fertility, are present in the cave.

Group.II,, is referred to as the “Altar of the Pristine Waters” and, to this day, holds a special place in Maya rituals; it is called the “store room” by archaeologists. At the foot of the limestone columns were placed ceramic urns, set there to collect virgin water or zuhuy’ha in Yucatec. Water drips from the stalactites above and is believed to be the most sacred water in Maya rituals, since it is collected from stalactites, the “nipples of the earth”. It is sanctified because it never touches the ground and, being transferred directly from Nature (the rock) to Culture (the manmade urns), acquire the highest ritual value, and is still practiced in today’s rituals.

Group.II,, is referred to as the “Altar of the Pristine Waters” and, to this day, holds a special place in Maya rituals; it is called the “store room” by archaeologists. At the foot of the limestone columns were placed ceramic urns, set there to collect virgin water or zuhuy’ha in Yucatec. Water drips from the stalactites above and is believed to be the most sacred water in Maya rituals, since it is collected from stalactites, the “nipples of the earth”. It is sanctified because it never touches the ground and, being transferred directly from Nature (the rock) to Culture (the manmade urns), acquire the highest ritual value, and is still practiced in today’s rituals.

The importance of the rain god Cha’ak, and its multiple representations in Mesoamerican cosmology, essentially revolve around a simple word: water. The peninsula lies nineteen degrees north of the equator. Its geographical location and Maya lands further south enjoy only two seasons: dry and wet. If the rains do not come on time, crops are short or fail entirely. Famine may then endure with its retinue of malevolent deities and social disruptions together with hunger, and the fear of tomorrow.

On the underground lakeshore is Group.IIIa with a peculiar arrangement of small ceramic censers, plates and small spindle whorls, as well as stone mini metates, and manos; the largest number of offerings in Group.III. How and why they were displayed is not known, nor the reason for the assemblage and their respective numbers. Their small sizes are particular to Tlaloc offerings; their purpose, point to their use by small children. Of note is the fact that their display today was set by archaeologists, since we do not know of their disposition in ancient times.

Ethnographic accounts throughout Mesoamerica document miniature objects as offerings, often associated with rain-making rituals. Young children, particularly girls were favored by Tlaloc, god of rain and thunder. The presence of spindle whorls underlines the symbolic significance of weaving that has been documented to be associated with females and Chak’Chel (great or red rainbow), the aged goddess of curing and childbirth in Classic times. She is also known as Ix Chel (lady rainbow), from her shrines on the islands of Isla Mujeres and Cozumel. To the Maya, rainbows came from the underworld and were dreaded omens of illness and death (Sharer & Traxler, 1994 :735).

Ethnographic accounts throughout Mesoamerica document miniature objects as offerings, often associated with rain-making rituals. Young children, particularly girls were favored by Tlaloc, god of rain and thunder. The presence of spindle whorls underlines the symbolic significance of weaving that has been documented to be associated with females and Chak’Chel (great or red rainbow), the aged goddess of curing and childbirth in Classic times. She is also known as Ix Chel (lady rainbow), from her shrines on the islands of Isla Mujeres and Cozumel. To the Maya, rainbows came from the underworld and were dreaded omens of illness and death (Sharer & Traxler, 1994 :735).

Group.IIIb is referred to as the “Waterway” now mostly flooded, because it is located close to the top of the water table. The underground lake extends about 115ft/35m from the shore, then dips below the ceiling of the cave and turns northeast for another 330ft/100m, before rising again above the water table reaching Group.IV, not accessible today. Investigators found ceramics and stone censers in the water and on limestone outcrops. At the end of the elongated lake, is a chamber that seems to be the limit of human penetration in this direction. The average depth is 5ft/1.5mt, with about half that depth in mud (Andrews, 1970:12-13).

On the muddy floor of the waterway were scattered offerings, such as Tlaloc effigy censers, studded censers and a variety of pottery offerings, with a distribution densest near the shore. According to Andrews (1970), at least four passages lead to underground water pools, the main reasons for the cave’s long period of use for this area, where the water table lay 65-76ft/20-23m below the surface.

Long before Tlaloc, the sacred cave was used for the same purposes by its predecessor, the Maya Cha’ak. The cave was “returned” to the Maya deity during a complex and elaborate ritual ceremony, the “Reverent Message to the Lords” that started on the early hours of October 13, 1959, and lasted 3 days and nights. But not before Maya h’men or shamans from the vicinity, through ancient rituals and offerings pacified the deities in the cave, the Yum Balames, to safely allow non-Maya to enter the hallowed precinct (Andrews, 1970:72).

Caves were believed to be the birthplace where humans were born and set forth on earth at the beginning of time, and where they would return at the end of their days. Ancestors dwelling in caves are trusted to interact with the World Above. No less than the sacred earth, caves are believed to be the meeting grounds between humans and the divine.

Private Tour: Chichen Itza Aboard Deluxe Van with Lunch

References:

Balankanche, throne of the tiger priest – E. Willys

Andrews.IV – MARI-Middle American Research Institute at Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, 1970

The Ancient Maya – Sharer & Traxler, Standford U. Press, Stanford, CA, 1994:735.

Chichén Itzá – Román Piña Chan, Fondo de Cultura Econòmica, Mexico,1980

Maya History and Religion – J. Eric Thompson, University of Oklahoma Press, 1970

Private Tour: Chichen Itza, Ek Balam Cenote, and Tequila Factory

About the author:

Freelance writer-photographer, George’s mayaworldimages.com focus on the photography of pre-Columbian archaeological sites in Mexico and the Americas. The other site georgefery.com is concerned with history and travel stories that address a number of topics, from history to day living in various countries and cultures, food, architecture and people.

Long-Form articles in georgefery.com are dedicated to ongoing research papers on Maya and other cultures of the Americas. Fellow member of the Institute of Maya Studies, Miami, FL instituteofmayastudies.org and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org . Also a member in good standing with the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org . the Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX dma.org , and the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org Contact: George Fery – 5200 Keller Springs Road, Apt. 1511, Dallas, Texas 75248 – T. (786) 501 9692 – gfery.43@gmail.com and hello@georgefery.com

All photos by George Fery

Private Tour Chichen Itza, Cenote and Unique Mayan Ritual in Temazcal