Muktinath, Nepal

by Don Messerschmidt

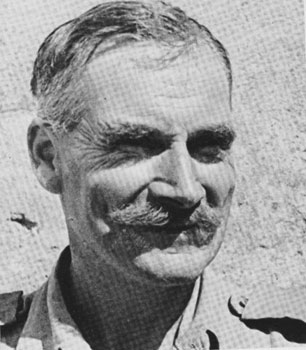

Well over a half century ago the inveterate British mountaineer and travel writer, H.W. ‘Bill’ Tilman (b.1898), was the first European to trek across some of the highest parts of Nepal. It was 1949, and one of his stops was the sacred Hindu/Buddhist pilgrimage shrine of Muktinath, near the Tibet border on the north side of the Annapurna massif.

Well over a half century ago the inveterate British mountaineer and travel writer, H.W. ‘Bill’ Tilman (b.1898), was the first European to trek across some of the highest parts of Nepal. It was 1949, and one of his stops was the sacred Hindu/Buddhist pilgrimage shrine of Muktinath, near the Tibet border on the north side of the Annapurna massif.

Today, Muktinath is a major stop on the popular ‘Round annapurna’ trekking route, the first stop after crossing the 17,769 Thorung La into the district of Mustang (pronounced ‘moose-tong’). I’ve been to Muktinath several times, and have always been puzzled by Tilman’s description of it. In his book, Nepal Himalaya (1952), he describes it as a “resort”. To be sure, it is an alluring and austere place, but why did he call it a “resort”?

In Tilman’s time Nepal was run by the Rana family of hereditary prime ministers, ensconced in sumptuous palaces in Kathmandu. They allowed only a few scholars and diplomats to visit their land-locked mountain kingdom, and then only to the Kathmandu valley via the arduous foot track up from India. A century earlier, the Rana autocrats had wrested control of the country away from the Shah kings, then locked the royals away in the palace, incommunicado, trotting them out on ceremonial occasions to appease the peasants who believed each sovereign to be Lord Vishnu reincarnate.

Tilman was lucky. He was neither a diplomat nor a scholar, but he managed to persuade the Ranas to let him and a few colleagues venture beyond Kathmandu into the high mountains around Annapurna at the west and Mount Everest in the eastern hills.

By 1949, Rana suzerainty had weakened under popular pressure to restore the monarchy, and after 1951 when King Tribhuvan regained the power of his throne he opened the kingdom to the outside world. Almost immediately, mountaineers sought permission to climb Nepal’s highest peaks. In 1952, a French expedition summited Annapurna-I (26,545 ft), and a year later the Brits successfully topped Everest (29,029 ft). Both expeditions followed in some of Bill Tilman’s footsteps.

Within a decade mountaineers, rural development specialists, missionaries, itinerant trekkers and others, including American Peace Corps volunteers like me, were familiar sights on the trails of Nepal. Most were short-time visitors, but some of us came to live in the rural villages as aid workers, hiking the mountain tracks for pleasure on weekends and holidays.

Tilman’s Nepal Himalaya was our guide. It’s a classic of the Himalayan literature, one that belongs in the personal library of every ardent or aspiring mountaineer and trekker. It is notable not only for its descriptions of the medieval-like conditions of rural Nepal over half a century ago, but for the author’s unique candor and style.

Tilman’s Nepal Himalaya was our guide. It’s a classic of the Himalayan literature, one that belongs in the personal library of every ardent or aspiring mountaineer and trekker. It is notable not only for its descriptions of the medieval-like conditions of rural Nepal over half a century ago, but for the author’s unique candor and style.

Out on the trail, Tilman and his companions acquired a liking for the local spirits, a type of rice liquor called raksi and a watery rice or millet ferment known as chang. One afternoon at a village called Gudel, south of Everest, he gazed across the valley to Bung, the next day’s destination. The name Bung, he wrote, “appeals to a music-hall mind,” and it moved him to pen this ditty:

For dreadfulness naught can excel

The prospect of Bung from Gudel;

And words die away on the tongue

When we look back at Gudel from Bung.

When they arrived at Bung, Tilman and his companions hoped to acquire some spirits to warm heart and soul and sooth their aching feet. But, alas, “its abundant well of good raksi, on which we were relying, had dried up.”

Tilman’s prose was more serious, informative and insightful, but no less entertaining. For example, in one chapter of his book he wrote, tongue-in-cheek, that he and his companions failed to summit Annapurna-IV (24,688 ft) simply because of an “inability to reach the top.”

Tilman’s prose was more serious, informative and insightful, but no less entertaining. For example, in one chapter of his book he wrote, tongue-in-cheek, that he and his companions failed to summit Annapurna-IV (24,688 ft) simply because of an “inability to reach the top.”

Muktinath shrine at 12,474 feet was not far away, and was a great attraction to Tilman. He characterized the countryside as a “woodless waste of yellow, grey and black hills … a barren landscape.” Then, looking westward from the shrine, down across the great crack in the Himalayas through which Kali Gandaki river flows south toward the Ganges, he wrote that “It runs at the bottom of a deep trench as if ashamed of hurrying stealthily by, withholding its life-giving water from so thirsty a landscape…”

On this barren terrain, Muktinath appeared green and luxuriant, like an oasis in a mountain desert, a place where devout Hindu and Buddhist pilgrims have been going to worship over the past several thousand years (according to ancient Vedic scriptures).

His party “camped near the topmost house of the straggling village where our arrival created no stir. A place to which several thousand pilgrims come every year must be accustomed to strange sights.”

His party “camped near the topmost house of the straggling village where our arrival created no stir. A place to which several thousand pilgrims come every year must be accustomed to strange sights.”

Tilman said, Muktinath is a “celebrated Hindu pilgrim resort.” This baffled me. “Celebrated”? — Yes; it is well known and extolled across South Asia. But “resort”? — No; Nothing about Muktinath in Tilman’s day, or now, is even remotely suggestive of fancy resort-like facilities or attractions.

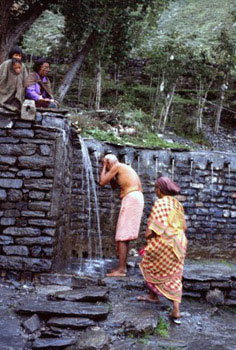

The cold water springs that Tilman describes gushing copiously from the mountainside above the shrine are believed by the faithful to flow underground directly from sacred Lake Manosarovar near Mount Kailash in western Tibet. All pilgrims to Muktinath are expected to bathe in the frigid waters, to cleanse body and soul from sin and to attain spiritual ‘liberation’ or ‘salvation’, the mukti that gives the shrine its name.

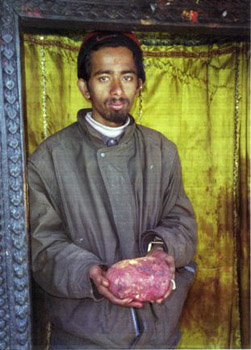

Tilman noted that Muktinath “owes its sanctity to the presence of the thrice-sacred ‘shaligram’,” the local name for black ammonite fossils found in abundance in this locale. Hindus worship the coiled shaligrams as representations of Lord Vishnu. Buddhists consider them to represent Gawo Jogpa, a serpent deity. Geologically they date back 165 million years to a time when this high-rise landscape lay covered by mud at the bottom of the Tethys Sea. Back then, long before the Himalayas were formed, the shallow Tethys separated Gondwanaland (today’s Indian subcontinent) from Laurasia (the Tibetan plateau). You can well imagine the looks of wonder in the eyes of today’s pilgrims from the plains upon finding the encrustations of ancient sea creatures so high in the mountains.

Tilman noted that Muktinath “owes its sanctity to the presence of the thrice-sacred ‘shaligram’,” the local name for black ammonite fossils found in abundance in this locale. Hindus worship the coiled shaligrams as representations of Lord Vishnu. Buddhists consider them to represent Gawo Jogpa, a serpent deity. Geologically they date back 165 million years to a time when this high-rise landscape lay covered by mud at the bottom of the Tethys Sea. Back then, long before the Himalayas were formed, the shallow Tethys separated Gondwanaland (today’s Indian subcontinent) from Laurasia (the Tibetan plateau). You can well imagine the looks of wonder in the eyes of today’s pilgrims from the plains upon finding the encrustations of ancient sea creatures so high in the mountains.

The most astounding sign of the gods, however, are several small natural gas vents burning from earth, water and stone, enshrined in a temple called Jwala Mai, a short walk south of the Vishnu Mandir. For the donation of a few rupees, the faithful can view the tiny blue flames burning dimly under a dark altar from which several grave idols stare unmoved.

The fires of Jwala Mai were first described in English by David Snellgrove, a British Tibetologist who visited Muktinath in 1956. In his book, Himalayan Pilgrimage (1961), Snellgrove wrote that “The flames of natural gas burn in little caves at floor level in the far right-hand corner. One does indeed burn from earth; one burns just beside a little spring (‘from water’); and one ‘from stone’ exhausted itself two years ago [1954] and so burns no longer, at which local people express concern.”

The fires of Jwala Mai were first described in English by David Snellgrove, a British Tibetologist who visited Muktinath in 1956. In his book, Himalayan Pilgrimage (1961), Snellgrove wrote that “The flames of natural gas burn in little caves at floor level in the far right-hand corner. One does indeed burn from earth; one burns just beside a little spring (‘from water’); and one ‘from stone’ exhausted itself two years ago [1954] and so burns no longer, at which local people express concern.”

The flames are a focal point of immense curiosity and veneration. Pilgrims stand in awe of them as something magical, a sign from the gods. Because fire and water are incompatible in Nature, they are considered as super-natural; hence, the ‘miracle’ of Jwala Mai.

In Tibetan, Muktinath is Chumig Gyatsa, meaning the sacred place of “a hundred-odd springs.” Most pilgrims at Muktinath are Hindus, but those in charge of the daily upkeep of the entire complex are Buddhist nuns of the ancient Tibetan Nyingmapa sect. That many such high mountain sites are revered equally by followers of both religions is an example to the world of a remarkable tolerance and religious syncretism.

On the secular side of Muktinath, the physical facilities available to pilgrims consist primarily of uncomfortable cold stone shelters wide open to the elements. In recent years, several tourist hotels and trekkers’ guesthouses have been built at Rani Pauwa (‘Queen’s Resthouse’), a small settlement below the shrine. They bear such names as Shri Muktinath Hotel and Royal Mustang Hotel, and one that is inexplicably named after Bob Marley, the renowned Rastafarian musician.

On the secular side of Muktinath, the physical facilities available to pilgrims consist primarily of uncomfortable cold stone shelters wide open to the elements. In recent years, several tourist hotels and trekkers’ guesthouses have been built at Rani Pauwa (‘Queen’s Resthouse’), a small settlement below the shrine. They bear such names as Shri Muktinath Hotel and Royal Mustang Hotel, and one that is inexplicably named after Bob Marley, the renowned Rastafarian musician.

There are no luxury lodgings with cushy rooms. No spa or heated pool or jacuzzi to soak in while marveling at the wilder-than-Switzerland mountain scenery. Nothing of the sort. It’s all relative, of course, for a pan of tepid water for bathing and a bed where the weary traveler can rest certainly feel luxurious after sweating up the mountain trail.

Muktinath is a cold, forbidding, austere place all year round, not a “resort” in any contemporary sense of the word. So, where did Bill Tilman get the notion? It’s a linguistic conundrum that have long assumed to be rooted in some arcane usage. Or, was it merely a Tilmanesque expression derived from his mid-century British English style of speech?

I set out to trace the etymological roots of “resort,” the noun. In Roget’s Thesaurus I found a long list of synonyms: haunt, hangout, playground, vacation spot, gathering place, club, and casino. A place for recreation, like a ski lodge. A health spa, baths or springs. All the things we expect a “resort” to be. The only association between these contemporary descriptors and Muktinath’s ascetic reality are those “hundred-odd” cold mountain springs. But I can’t imagine Tilman cavorting playfully in the frigid waters then calling it a “resort.”

I set out to trace the etymological roots of “resort,” the noun. In Roget’s Thesaurus I found a long list of synonyms: haunt, hangout, playground, vacation spot, gathering place, club, and casino. A place for recreation, like a ski lodge. A health spa, baths or springs. All the things we expect a “resort” to be. The only association between these contemporary descriptors and Muktinath’s ascetic reality are those “hundred-odd” cold mountain springs. But I can’t imagine Tilman cavorting playfully in the frigid waters then calling it a “resort.”

I discovered an obscure Internet website advertising religious excursions in India, for the rich, to special tour destinations called “pilgrim resorts.” From the portrayal, they sound only slightly more comfortable than Muktinath. I went on, searching and crawling deeper into the web and eventually came across two century-old sources that brought me face-to-face with Tilman’s usage. One was a 1905 European travel guide describing a Christian “pilgrimage-resort” (with the dash) in northern France. The other was a 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica reference to places of prayer in Jerusalem called “pilgrim-resorts.”

At last, Tilman’s “resort” makes sense. It meant a place for spiritual meditation and prayer, not its modern implication as a place to go for physical indulgence and pleasure. Tilman was surely familiar with that archaic meaning of the term, for he’d undoubtedly seen more than one such austere “pilgrim resort” during his travels in South Asia as a soldier of the British Raj and as the intrepid mountaineer-adventurer and writer that he became. Or did it simply come to him one evening after drinking raksi or chang at Gudel or Bung?

Author’s Note: The first edition of Tilman’s Nepal Himalaya (1952) is now a rare book. Fortunately, it has been reprinted in Tilman’s Seven Mountain-Travel Books by The Mountaineers (Seattle) and Diadem Books (London) (1983). There are also several biographies of him as mountaineer (in his youth), sailor (in later life), and discerning travel writer (life-long).

Pilgrimage Nepal Tour (Pashupatinath Muktinath Janakpur Manokamana Darshan)

If You Go:

Nepal Travel, Trekking & Tours Info

About the author:

Anthropologist Don Messerschmidt was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Nepal from 1963 to 1965 who stayed on for most of the rest of time as a development worker, teacher and writer. Today he is a writer, and past editor of Kathmandu’s ECS Nepal magazine (archived at www.ecs.com.np) featuring stories of Himalayan culture, history, the arts, travel, and adventure sports. He has also written several books, including Big Dogs of Tibet and the Himalayas: A Personal Journey (Orchidbooks, 2010). Don writes from his home near Portland, Oregon, where he can be contacted at don.editor@gmail.com.

Photo credits:

All photos are by Don Messerschmidt.