Memoirs of a Single Western Nurse in Dhahran

by Anup Parmar

As I saw the police approach the taxi I was riding in with my handsome male companion on that lonely desert highway, my heart started to pound. Images of my passport with a deportation stamp “PROSITUTION” flashed thru my mind. This was one of the realities of a woman getting in a cab with a man who was not her husband, father, brother or son in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It did not even matter, as in this case, that the man who accompanied me was very committed to his young charming boyfriend.

How did I get to that lonely desert highway in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia? Who was I, this foreign western woman draped in a long black robe sitting on the backseat of the cab? What was I doing there? The answers I prepared in my mind for the Saudi police were simplified and well rehearsed after one year of living and working in the land of oil and sand.

How did I get to that lonely desert highway in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia? Who was I, this foreign western woman draped in a long black robe sitting on the backseat of the cab? What was I doing there? The answers I prepared in my mind for the Saudi police were simplified and well rehearsed after one year of living and working in the land of oil and sand.

In 1998, looking for adventure and a chance to travel the world, I went to work in Dhahran, a desert town on the Persian Gulf of Saudi Arabia. During my fourteen months there I had an opportunity to lead a life that is too surreal for most westerners comprehend, immersed in a fascinating culture. The King Fahd Military Medical Complex (KFMMC) was a military complex that included a 329-bed hospital and a health sciences college, which trained about 300 health professional students. The hospital provides primary, secondary and tertiary medical services to the armed forces personnel, their dependents and other “eligible citizens.” It also had outpatient departments to provide Arabic patients with primary care needs.

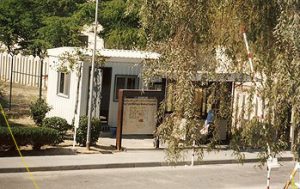

Rules and regulations were rigid, but the compound was new and modern with a weight room, swimming pool, bank, beauty salon, restaurant, post office and a small but efficient supermarket. Recreation facilities’ usage was divided into male and female times and strictly enforced. There was a women’s housing compound where single foreign women, such as myself, lived. It was enclosed by fifteen feet of barbed wire fence, guarded by Saudi military 24 hours a day. No men were allowed on the women’s compound and women were not permitted on the men’s area. Single women required passes to leave KFMMC. According to Saudi laws and customs a woman is the responsibility of her husband, father, brother or son and therefore can only travel with this male relative’s permission. Since all my male relatives were in North America, I needed special permission from the hospital to move around the country.

Rules and regulations were rigid, but the compound was new and modern with a weight room, swimming pool, bank, beauty salon, restaurant, post office and a small but efficient supermarket. Recreation facilities’ usage was divided into male and female times and strictly enforced. There was a women’s housing compound where single foreign women, such as myself, lived. It was enclosed by fifteen feet of barbed wire fence, guarded by Saudi military 24 hours a day. No men were allowed on the women’s compound and women were not permitted on the men’s area. Single women required passes to leave KFMMC. According to Saudi laws and customs a woman is the responsibility of her husband, father, brother or son and therefore can only travel with this male relative’s permission. Since all my male relatives were in North America, I needed special permission from the hospital to move around the country.

There was a curfew of 11pm on weeknights and 1:00am on weekends. To spend an overnight away from the compound you had to obtain a special pass. For a weekend pass within the Eastern Province, an invitation letter from a married couple was required, their personal information, copies of their employment documents and marriage certificate and at least 72 hours for Human Resources & Security to process all these documents. Travel outside of the Eastern Province required all of the above plus an airline ticket and 7-10 days for processing by Human Resources & Security. Our passes were obtained and returned at the Women’s Gate but checked again at two other gates before we could leave or return to KFMMC. Single men didn’t have curfew, or need to get any passes or anyone’s permission to travel around the country. It’s a man’s world in Saudi Arabia!

There was a curfew of 11pm on weeknights and 1:00am on weekends. To spend an overnight away from the compound you had to obtain a special pass. For a weekend pass within the Eastern Province, an invitation letter from a married couple was required, their personal information, copies of their employment documents and marriage certificate and at least 72 hours for Human Resources & Security to process all these documents. Travel outside of the Eastern Province required all of the above plus an airline ticket and 7-10 days for processing by Human Resources & Security. Our passes were obtained and returned at the Women’s Gate but checked again at two other gates before we could leave or return to KFMMC. Single men didn’t have curfew, or need to get any passes or anyone’s permission to travel around the country. It’s a man’s world in Saudi Arabia!

The recreation department sometimes arranged day excursions to local attractions. This was one of the few ways to explore the surrounding country since women were not legally permitted to drive and public transportation system was not user friendly for women. KFMMC provided private bus services every evening and Thursday afternoons between our compound and Al Khober, the closest town for shopping about 35 minutes away. These buses dropped you in downtown and two and half hours later picked you up from the same place. There were separate buses for women, men and families.

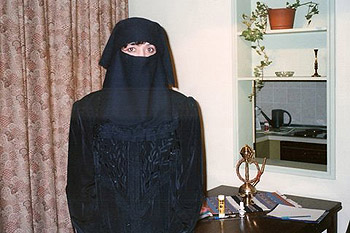

Shopping in Al Khobar was an experience like no other. All women, including non-Muslim foreigners are required to wear an abbhaya (the long loose black robes the women must cover themselves with according to Saudi customs and laws). We wore these long black robes in the blazing sun with temperatures up to 50C. The shops were usually air-conditioned but during prayer call they shut down while male staff go to pray at the local mosque. While we waited in the blistering heat, sometimes we took advantage of the men and the religious police’s absence to subversively take photos. (It is forbidden to take pictures of women, public buildings and most other public areas in Saudi.)

Shopping in Al Khobar was an experience like no other. All women, including non-Muslim foreigners are required to wear an abbhaya (the long loose black robes the women must cover themselves with according to Saudi customs and laws). We wore these long black robes in the blazing sun with temperatures up to 50C. The shops were usually air-conditioned but during prayer call they shut down while male staff go to pray at the local mosque. While we waited in the blistering heat, sometimes we took advantage of the men and the religious police’s absence to subversively take photos. (It is forbidden to take pictures of women, public buildings and most other public areas in Saudi.)

All the shops in Al Khobar including lingerie, cosmetic and jewelry shops are operated by men. As there are no fitting rooms you buy your clothing, take them home to try them on, then if they don’t fit, take them back and repeat the process. The proprietors of cosmetic shops give advice on make-up to the Saudi women even though their faces are totally covered. Western women get the free advice, great discounts and bags full of free samples of the finest perfumes and beauty products from France. One jewelry shop gave my single friends and I substantial mafi husband (no husband) discounts because we didn’t have husbands to buy us nice things. In a gold shop when my friend wanted to purchase a necklace, after the usual bartering, when he saw my camera, the young shopkeeper, in exchange for an enormous discount, requested I take a picture of him posed with my blue-eyed, strawberry blonde friend.

Most social activities were segregated by nationals and non-nationals. Alcohol is illegal in Saudi however there were some pubs and alcohol was usually available at the many ex-pat parties. (Many ex-pats made their own moonshine.) The KFMMC was located in the middle of the desert enclosed by a wire fence. No one was permitted to go into the desert for “security reasons.” Guards drove around the compound every 45 minutes. One New Years day, a group of us decided to have a pot luck picnic on a tiny oasis in this beautiful but prohibited desert. We dug the sand from underneath the fence and placed large rocks to cover it. The next day, we moved the rocks, crawled under the fence then moved the rocks back to hide our escape route before the security drove by. Having parties always carried some risk.

Most social activities were segregated by nationals and non-nationals. Alcohol is illegal in Saudi however there were some pubs and alcohol was usually available at the many ex-pat parties. (Many ex-pats made their own moonshine.) The KFMMC was located in the middle of the desert enclosed by a wire fence. No one was permitted to go into the desert for “security reasons.” Guards drove around the compound every 45 minutes. One New Years day, a group of us decided to have a pot luck picnic on a tiny oasis in this beautiful but prohibited desert. We dug the sand from underneath the fence and placed large rocks to cover it. The next day, we moved the rocks, crawled under the fence then moved the rocks back to hide our escape route before the security drove by. Having parties always carried some risk.

The Health Records Department consisted of an American woman, myself and twenty-five hard working, enthusiastic female clerical and technical staff from the developing countries. Several HIMP male students did practicums on various days of the week. We also had two Saudi HIMP graduates from the college interning with us for one year. The Saudi government is trying to train its own health care workers to replace the ex-pats it has relied on for decades. The HRD was open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. I worked nine hours a day, Saturdays to Wednesdays. My duties included clerical, technical and administrative duties of a typical health records department as well as planning and supervising the Saudi interns’ and practicums for the students. The Health Information Services Program at the college offered a two-year program but only for Saudi men. Women attended an all female school in Riyadh. A six-week practicum for female students was offered at a different site due to the country’s rigid laws and customs. It was during the Saudi women’s practicum that I got to learn more about the ways of women behind the veil

According to Saudi Arabian customs, girls become women when they start to menstruate. At this time they must begin to wear the abhyahas and burkakhas, the black veil required to veil themselves from all men expect for their fathers, brothers, grandfathers and husbands. All Muslim female staff at KFMMC had to cover their heads regardless of nationality. As a non-Muslim western woman, I was permitted more liberties. I wore a “pre-approved” uniform provided to me by the hospital: a loose white lab coat made of heavy polyester-cotton blend over long dark navy blue pants. Buttons had to be done up and I wore a high neck T-shirt or blouse underneath and close-toed shoes with socks. On the compound, we westerners didn’t have to wear abhyahas but were required to dress “conservatively” in loose clothing with arms and legs covered. Outside, we wore abhyahas and carried headscarves because of the religious police. One day while shopping with a friend, an old Saudi man began to bang his cane on the sidewalk, pointing at my friend’s long fair hair.

“Sister! Abhyaha!” he screamed. “Sister! Abhyaha! Sister! Abhyaha!” He didn’t stop until she pulled out a headscarf and covered her head – one of those surreal “only in Saudi Arabia” moments.

As I sat in the taxi on that dark highway I thought back on my time in Saudi Arabia. It was hard for me to understand and fully accept many of the customs, but just as I thought the life of a woman there was a surreal experience, my own single childless state coupled with my constant solo travels to remote parts of the world, was too surreal for most Saudi women to comprehend.

As I sat in the taxi on that dark highway I thought back on my time in Saudi Arabia. It was hard for me to understand and fully accept many of the customs, but just as I thought the life of a woman there was a surreal experience, my own single childless state coupled with my constant solo travels to remote parts of the world, was too surreal for most Saudi women to comprehend.

”I’m from Canada,” I explained to the military policeman as he scrutinized my male friend and I. “I work as a health records technician at King Fahd Military Medical Complex in Dhahran. I came to work here because I love foreign cultures and customs but I’m returning to Canada soon as I have finished my one year contract.”

He looked intently at me. “You are going back to Canada?”

“Yes. I’m on my way back to KFMMC from my marsallama (farewell) dinner in Al Khobar.” I felt sick with nervousness. Would he believe me?

To my relief, he handed my work documents back to me unstamped. “Your family will be happy to see you,” he said. Then he smiled and waved us on. “I hope you enjoyed your stay in the Kingdom. Salem Egem (Good Night).”

More Information:

Profiles of Saudi Arabia: Dharhan

King Fahd Military Medical Complex

About the author:

Anup Parmar grew up in Vancouver. She taught and trained students in health care and taught English in Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, China and Poland. Anup has enjoyed traveling to many remote and isolated places around the globe. She currently teaches health care workers in Vancouver.

Contact: anup_parmar_99@yahoo.com

Photo credits:

All photos are by Anup Parmar.