by John Thomson

by John Thomson

I’m in Glasgow visiting relatives, recalled to the city by blood ties and circumstance. Glasgow is Scotland’s largest city, a little shabby in parts I must admit, its once busy dockyards replaced by a shopping mall, an amusement centre and a transportation museum. Thankfully, many of Glasgow’s magnificent sandstone buildings remain intact, a reminder of its better days when the city was flush with pride and Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh was at the top of his game. The Mackintosh story, like the city itself, is a bittersweet tale of success, decline and ultimate redemption. Not familiar with the name? You’ll recognize his furniture. His straight, high-backed chairs are cultural icons often associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement and although I’m not a fan of his chairs – too rigid for me – I have to acknowledge their importance.

I’m in Glasgow visiting relatives, recalled to the city by blood ties and circumstance. Glasgow is Scotland’s largest city, a little shabby in parts I must admit, its once busy dockyards replaced by a shopping mall, an amusement centre and a transportation museum. Thankfully, many of Glasgow’s magnificent sandstone buildings remain intact, a reminder of its better days when the city was flush with pride and Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh was at the top of his game. The Mackintosh story, like the city itself, is a bittersweet tale of success, decline and ultimate redemption. Not familiar with the name? You’ll recognize his furniture. His straight, high-backed chairs are cultural icons often associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement and although I’m not a fan of his chairs – too rigid for me – I have to acknowledge their importance.

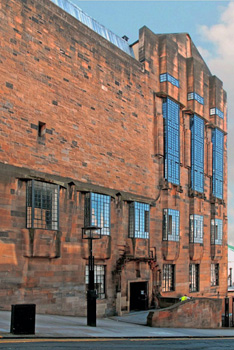

I start my Glasgow tour on Sauchiehall (pronounced Sock-ee-hall) Street and work my way west. Glasgow converted its two main downtown thoroughfares, Buchanan and Sauchiehall Streets into pedestrian malls years ago and getting around the central core is a pedestrian’s dream. A gentle rain sprinkles the pavement but as soon as it starts, it stops. I’m barely wet. I climb Scott Street to the Glasgow School of Art considered the pinnacle of Mackintosh’s architectural career. Completed in 1909, it’s an imposing structure with a domineering command of its surroundings. It reminds me of a fortress. The western wall is tight and dense with narrow loopholes from which I imagine the inhabitants, if they were medieval archers, could shoot arrows if the city were under siege. The northern wall on the other hand has lots of large windows giving it an airy feel and letting in lots of light too. After all, this is an art school. Form follows function.

I start my Glasgow tour on Sauchiehall (pronounced Sock-ee-hall) Street and work my way west. Glasgow converted its two main downtown thoroughfares, Buchanan and Sauchiehall Streets into pedestrian malls years ago and getting around the central core is a pedestrian’s dream. A gentle rain sprinkles the pavement but as soon as it starts, it stops. I’m barely wet. I climb Scott Street to the Glasgow School of Art considered the pinnacle of Mackintosh’s architectural career. Completed in 1909, it’s an imposing structure with a domineering command of its surroundings. It reminds me of a fortress. The western wall is tight and dense with narrow loopholes from which I imagine the inhabitants, if they were medieval archers, could shoot arrows if the city were under siege. The northern wall on the other hand has lots of large windows giving it an airy feel and letting in lots of light too. After all, this is an art school. Form follows function.

I saunter inside. “Where dae ye think yer goin’?” yells the security guard. This is functioning workspace and I didn’t see the sign that says tourists must report to the front office for an escorted tour. My bad. I did manage to steal some furtive glances, though, during my brief and illegal visit. I see that Mackintosh designed the School’s interiors as well, repeating his favourite themes, squares and rectangles in the light fixtures and wall decorations. His wife Margaret, an artist in her own right, contributed Art Nouveau floral tiles. (A major fire closed interior tours shortly after I left Scotland but the building can still be seen from the street while it’s being rebuilt).

Mackintosh was not only an architect but a designer too and the original Willow Tea Room on Sauchiehall is a prime example of his handiwork. Recruited by local businesswoman and teetotaller Catherine Cranston in 1896 to dress up her establishments, Mack designed everything – tables, chairs, room dividers, wall decorations, napkins and cutlery. The Tea Room, one of two in the city, has been preserved as a Mackintosh museum with the original stained glass door and replica furniture and yes, they still serve tea. Angularity is the prevailing theme – there are those high backed chairs again – and everything conforms to Mackintosh’s singular, unifying concept.

Mackintosh was not only an architect but a designer too and the original Willow Tea Room on Sauchiehall is a prime example of his handiwork. Recruited by local businesswoman and teetotaller Catherine Cranston in 1896 to dress up her establishments, Mack designed everything – tables, chairs, room dividers, wall decorations, napkins and cutlery. The Tea Room, one of two in the city, has been preserved as a Mackintosh museum with the original stained glass door and replica furniture and yes, they still serve tea. Angularity is the prevailing theme – there are those high backed chairs again – and everything conforms to Mackintosh’s singular, unifying concept.

I jump on the subway, the third oldest in the world I’m told after London and Budapest. The cars are tiny compared to North American stock. “Don’t call it the Tube,” my relatives told me. “You’re not in London and it will only tick off the locals.” Glasgow takes pride in differentiating itself from England. In Glasgow, the underground is not The Underground.

I get off at the Kelvinhall stop and walk to the Hunterian Art Gallery on the grounds of the University of Glasgow. Mack’s 1906 residence or at least parts of it – the hall, dining room, living room and the main bedroom – have been moved from their original location and reassembled here for public display. It’s breathtaking in its simplicity. Mackintosh and Margaret have designed everything themselves right down to the fireplace decorations. They even knocked down interior walls to create more space, a radical innovation at the turn of the nineteenth century. Sunlight bounces off the stark white walls accentuating the open plan. The angular motif that I first saw at the Willow Tea Room, lots of right angles and variations on the square, is repeated in the floor, the furniture and the wall decorations. Everything is co-ordinated. A bit too co-ordinated. I feel like I’m in a museum piece, which of course I am, and long for the remains of a half-eaten breakfast on the dining room table or a pile of dirty clothes at the foot of those oh-so-perfect matching beds. I wonder if Mack and his wife ever felt the same way. Probably not. I have to admit the duo were ahead of their time though. Their turn-of-the-century digs look like they belonged in the 1930’s.

I get off at the Kelvinhall stop and walk to the Hunterian Art Gallery on the grounds of the University of Glasgow. Mack’s 1906 residence or at least parts of it – the hall, dining room, living room and the main bedroom – have been moved from their original location and reassembled here for public display. It’s breathtaking in its simplicity. Mackintosh and Margaret have designed everything themselves right down to the fireplace decorations. They even knocked down interior walls to create more space, a radical innovation at the turn of the nineteenth century. Sunlight bounces off the stark white walls accentuating the open plan. The angular motif that I first saw at the Willow Tea Room, lots of right angles and variations on the square, is repeated in the floor, the furniture and the wall decorations. Everything is co-ordinated. A bit too co-ordinated. I feel like I’m in a museum piece, which of course I am, and long for the remains of a half-eaten breakfast on the dining room table or a pile of dirty clothes at the foot of those oh-so-perfect matching beds. I wonder if Mack and his wife ever felt the same way. Probably not. I have to admit the duo were ahead of their time though. Their turn-of-the-century digs look like they belonged in the 1930’s.

My last visit takes me to the Lighthouse, a gallery and design incubator originally built for a local newspaper and now repurposed as Scotland’s National Centre for Architecture and Design. It’s here that I find the completion of the Mackintosh story. The entire third floor is devoted to his life and his works.

I learn that young Mackintosh was quite the celebrity when he completed the Glasgow School of Art in 1909 but when he left his employers, Honeyman and Keppie, to strike out on his own, tastes changed and his business faltered. He and his wife Margaret retreated to London to concentrate on textile design. And when that didn’t pan out the couple eventually retired to southern France where Mackintosh renounced architecture entirely and spent the rest of his life painting watercolours.

I learn that young Mackintosh was quite the celebrity when he completed the Glasgow School of Art in 1909 but when he left his employers, Honeyman and Keppie, to strike out on his own, tastes changed and his business faltered. He and his wife Margaret retreated to London to concentrate on textile design. And when that didn’t pan out the couple eventually retired to southern France where Mackintosh renounced architecture entirely and spent the rest of his life painting watercolours.

Mackintosh returned to the UK in 1927 and died the following year of cancer. For awhile it looked like the world had forgotten the innovative Scot but in 1973 a local non-profit society was created to maintain his buildings and recognize his accomplishments. Thanks to the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society many of his buildings were preserved and his reputation solidified.

Today he’s Glasgow’s favorite son and the city isn’t shy about promoting him. He’s been immortalized, idolized and commercialized. It’s impossible to leave Glasgow without hearing his name, his handiwork or for that matter, a Mackintosh souvenir. One can’t have too many coffee mugs.

As I board the plane to return home, I ponder the Mackintosh phenomenon. Yes, his buildings are stunning. Built to withstand the Scottish climate, they’re solid, substantial structures in contrast to those flouncy neo-classical buildings in vogue at the time. Scholars have called the style Scottish Baronial, tying Mackintosh and his ideas to the Scottish Renaissance of the early twentieth century when there was a creative surge in Scottish arts and letters. Perhaps he deserves his fame because he stripped away superfluous decoration in favour of detail that complemented the building’s integrity, paving the way for Modernism. Perhaps it’s because he involved himself in total design – integrating architecture with wall treatments, light fixtures and furniture. Mack pre-dated future “starchitects” like Frank Gehry by decades. Perhaps it’s all of these things, a combination of accomplishments both historic and aesthetic.

As I board the plane to return home, I ponder the Mackintosh phenomenon. Yes, his buildings are stunning. Built to withstand the Scottish climate, they’re solid, substantial structures in contrast to those flouncy neo-classical buildings in vogue at the time. Scholars have called the style Scottish Baronial, tying Mackintosh and his ideas to the Scottish Renaissance of the early twentieth century when there was a creative surge in Scottish arts and letters. Perhaps he deserves his fame because he stripped away superfluous decoration in favour of detail that complemented the building’s integrity, paving the way for Modernism. Perhaps it’s because he involved himself in total design – integrating architecture with wall treatments, light fixtures and furniture. Mack pre-dated future “starchitects” like Frank Gehry by decades. Perhaps it’s all of these things, a combination of accomplishments both historic and aesthetic.

I went to Glasgow to visit relatives, not to bone up on architecture but I’m glad I wandered down the Mackintosh trail. I arrived a novice, barely familiar with his work, and left a believer, a convert to the cult of Mackintosh. But I still don’t like those stiff-looking chairs.

If You Go:

All things Mackintosh can be found at www.glasgowmackintosh.com. The site lists Mackintosh buildings, attractions and events.

I stayed at the four-star Millennium Hotel opposite Glasgow Square in the centre of town.

You can log onto Visit Scotland for links to other accommodations as well.

Loch Lomond and Glengoyne Whisky Distillery Half Day Tour from Glasgow

Photo credits:

Glasgow School of Art #1 by John a s / CC BY-SA

All other photos by John Thomson:

Central Glasgow, George Street

Central Glasgow, Buchanan Street

Glasgow School of Art, northern facade

Glasgow School of Art, western facade

The Entrance to the Lighthouse

The iconic Mackintosh chair

About the author:

Scottish-born John Thomson comes from a news and current affairs background. He writes for print, online and broadcast. A stickler for detail, he says “Braveheart” is an historical travesty. His forebearers never painted themselves blue nor flashed their buttocks in battle though he concedes Mel Gibson looked good in tartan.

London it isn’t – nor Edinburgh. There’s nothing twee, contrived, touristy or pretty-pretty about Glasgow. Glasgow is down-to-earth, has real character. It’s smart, gritty, witty, vibrant and alive. It’s the genuine article.

London it isn’t – nor Edinburgh. There’s nothing twee, contrived, touristy or pretty-pretty about Glasgow. Glasgow is down-to-earth, has real character. It’s smart, gritty, witty, vibrant and alive. It’s the genuine article. The Necropolis lies on a hill overlooking the city. All of Glasgow stretched out before us: the Tennent’s brewery close by, isolated tenement blocks, smaller brick-built houses, concrete offices and wind turbines on the moors, far on the horizon. Alan pointed out the place where his tenement home had once stood, long gone now. It had survived an incendiary bomb during the war (His mother, an ARP warden, had hosed down the fire in the attic herself) only for the building to be later demolished.

The Necropolis lies on a hill overlooking the city. All of Glasgow stretched out before us: the Tennent’s brewery close by, isolated tenement blocks, smaller brick-built houses, concrete offices and wind turbines on the moors, far on the horizon. Alan pointed out the place where his tenement home had once stood, long gone now. It had survived an incendiary bomb during the war (His mother, an ARP warden, had hosed down the fire in the attic herself) only for the building to be later demolished. The gravestones are filled with story and history. I could have spent hours there uncovering lives like John Ronald Ker’s: accidentally drowned while shooting wildfowl from a small boat off Contyre of Ronaghan at the early age of 21 – of a generous and amiable disposition and endearing qualities which made him so agreeable a companion, so good and true a friend. (July 1868)

The gravestones are filled with story and history. I could have spent hours there uncovering lives like John Ronald Ker’s: accidentally drowned while shooting wildfowl from a small boat off Contyre of Ronaghan at the early age of 21 – of a generous and amiable disposition and endearing qualities which made him so agreeable a companion, so good and true a friend. (July 1868)

A stained glass tells the story of St Mungo and the miracles associated with him (symbols that form the Glasgow coat of arms):

A stained glass tells the story of St Mungo and the miracles associated with him (symbols that form the Glasgow coat of arms): “I know,” said Alan. “It’s a mistake. Charlie took great delight in showing people his name on the memorial, claiming he was one of the living dead. He thought it a great joke.” “But how did he end up on the list?”

“I know,” said Alan. “It’s a mistake. Charlie took great delight in showing people his name on the memorial, claiming he was one of the living dead. He thought it a great joke.” “But how did he end up on the list?” We visited the Clydeside, currently being regenerated with its smart new Riverside Museum, a theatre – the Armadillo, and the science museum tower. Over in the West End we discovered a vibrant hub of fine eateries, trendy boutiques and night clubs set among the cleaned-up sandstone Victorian buildings; handsome historic university buildings and museums set in leafy parks and hilly bluffs.

We visited the Clydeside, currently being regenerated with its smart new Riverside Museum, a theatre – the Armadillo, and the science museum tower. Over in the West End we discovered a vibrant hub of fine eateries, trendy boutiques and night clubs set among the cleaned-up sandstone Victorian buildings; handsome historic university buildings and museums set in leafy parks and hilly bluffs.