by Rick Neal

As the decrepit bus flies around another corner, I rue my decision to take local transit into Guanajuato from the bus terminal. Is my life worth the few dollars I saved on cab fare? I see nothing that resembles a town as we roar full throttle through a series of tunnels. I hope the driver understood my request to be dropped off near the city center.

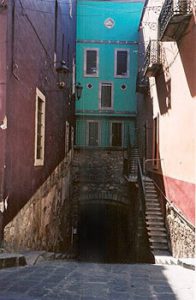

We screech to a halt in the middle of yet another tunnel. The driver jerks his thumb toward the door. I grab my backpack and jump off. I feel like I’m in a medieval dungeon, surrounded by high stone arches and damp, vaulted ceilings. Across the road is a stone staircase. I ascend to a panorama that plays like a scene from The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. The narrow street I’m on is clogged with people and traffic in every direction. Honking, belching cars compete with mariachi music that blares from a nearby café. Stately mansions and magnificent churches preside over the chaotic street scene.

Guanajuato is the liveliest of Mexico’s fabled silver cities. Located in the central highlands, four and a half hours north of Mexico City, Guanajuato (pronounced gwah-nah-WHAH-toh) was founded in the mid-1500s after rich silver veins were discovered nearby. The town soon developed into one of the country’s most important mining centers. For two hundred years these mines produced a third of the world’s silver. The residents flaunted their newfound wealth, producing some of Mexico’s most elaborate architecture. Today it is a place of underground tunnels, winding alleys, quaint plazas, and charming old hotels. Elegant theatres, imposing municipal buildings and beautiful churches from the colonial era make Guanajuato a high point of a Mexican holiday.

Guanajuato is the liveliest of Mexico’s fabled silver cities. Located in the central highlands, four and a half hours north of Mexico City, Guanajuato (pronounced gwah-nah-WHAH-toh) was founded in the mid-1500s after rich silver veins were discovered nearby. The town soon developed into one of the country’s most important mining centers. For two hundred years these mines produced a third of the world’s silver. The residents flaunted their newfound wealth, producing some of Mexico’s most elaborate architecture. Today it is a place of underground tunnels, winding alleys, quaint plazas, and charming old hotels. Elegant theatres, imposing municipal buildings and beautiful churches from the colonial era make Guanajuato a high point of a Mexican holiday.

I stand on Avenida Juarez, one of two main streets. The road runs down a narrow valley encircled by mountains; a montage of candy-coloured buildings sprawls up the valley walls on either side. The map in my guidebook indicates that my hotel is on a side road one block south, but the streets are an indistinguishable maze. After a frustrating search I find the hotel down an alley less than two blocks from my starting point. The Casa Kloster is charming and friendly, with a pretty courtyard shrouded in flowers. By now it’s late afternoon so the popular place is nearly full. With all the single rooms taken, I settle for a dorm, which is clean, comfortable, and at eleven dollars per night, a bargain.

The next day I get an early start and set out to explore this captivating town. My first stop is the forbidding Museo Regional Alhondiga de Granaditas, located between Juarez and Pocitos, the town’s other main artery. Built as a granary in the late 18th century, this grand building played a pivotal role during the 1810 War of Independence. After Miguel Hidalgo’s famous call for Independence in the nearby town of Dolores, the Spanish occupying troops barricaded themselves inside the Alhondiga. Although outnumbered by a rebel army of 20,000, it looked as if the Spanish would be able to hold out indefinitely. Then, under orders from Hidalgo, a young miner named El Pipila tied a stone slab to his back as a shield and, from a crouching position, set the wooden gates ablaze amidst a hail of bullets. The Spanish forces were overcome by smoke, allowing Hidalgo’s army to capture the Alhondiga and the town.

The next day I get an early start and set out to explore this captivating town. My first stop is the forbidding Museo Regional Alhondiga de Granaditas, located between Juarez and Pocitos, the town’s other main artery. Built as a granary in the late 18th century, this grand building played a pivotal role during the 1810 War of Independence. After Miguel Hidalgo’s famous call for Independence in the nearby town of Dolores, the Spanish occupying troops barricaded themselves inside the Alhondiga. Although outnumbered by a rebel army of 20,000, it looked as if the Spanish would be able to hold out indefinitely. Then, under orders from Hidalgo, a young miner named El Pipila tied a stone slab to his back as a shield and, from a crouching position, set the wooden gates ablaze amidst a hail of bullets. The Spanish forces were overcome by smoke, allowing Hidalgo’s army to capture the Alhondiga and the town.

However, their victory was short-lived as the Spanish retaliated with a vengeance, murdering local citizens at random. The heads of Hidalgo and other rebels were hung from hooks that can still be seen outside the Alhondiga. The fortress has since been converted into a museum and art gallery showcasing Guanajuato’s archeology and history. Spectacular murals above the staircases by Mexican artist Chavez Morado depict Guanajuato’s history in vivid detail.

From the Alhondiga I enter the jumble of winding streets that ascend the steep hills south of town. Main roads lead into narrow callejones (alleys) that turn into staircases that seem to go nowhere. The narrowest alley is named the Callejon del Beso (Alley of the Kiss). Legend has it that a courting couple whose parents disapproved of their romance could actually kiss from their opposing balconies.

From the Alhondiga I enter the jumble of winding streets that ascend the steep hills south of town. Main roads lead into narrow callejones (alleys) that turn into staircases that seem to go nowhere. The narrowest alley is named the Callejon del Beso (Alley of the Kiss). Legend has it that a courting couple whose parents disapproved of their romance could actually kiss from their opposing balconies.

After a grueling hike I reach a hilltop above the town, affording panoramic views of the city below and the surrounding green and tan-coloured hills. Here stands a statue of El Pipila, the hero who set fire to the Alhondiga gates in 1810. The pink-stoned statue shows El Pipila holding his torch high over the city. According to local legends he died in the battle but some versions claim he lived to an old age. At the base of the statue is an inscription: ‘Aun hay otras Alhondigas por incendiar’ “There are still other Alhondigas to burn”.

From this high vantage point I watch buses and trucks snake in and out of the tunnels. Although Guanajuato’s famous tunnels appear to be ancient, most are less than 100 years old. The oldest was constructed in 1905 along the dried-up Rio Guanajuato riverbed. The river was diverted after it flooded the city. Since then eight others have been built to ease the strain of increased traffic. Above ground streets are one-way and limited to buses and heavy vehicles.

From this high vantage point I watch buses and trucks snake in and out of the tunnels. Although Guanajuato’s famous tunnels appear to be ancient, most are less than 100 years old. The oldest was constructed in 1905 along the dried-up Rio Guanajuato riverbed. The river was diverted after it flooded the city. Since then eight others have been built to ease the strain of increased traffic. Above ground streets are one-way and limited to buses and heavy vehicles.

I hike back down to Avenida Juarez and stop at the lovely Jardin de la Union, Guanajuato’s main plaza. Surrounded by hotels, restaurants, and craft stores, it’s the social hub of the city, packed with locals of all ages and social backgrounds, who have come to eat ice cream, have a shoeshine, or listen to a jazz combo performing from the gazebo. The ramparts of the University of Guanajuato dominate the view above the town. The university students give a youthful vibrancy to the cityscape and provide a modern contrast to the colonial setting.

Across the street is the Teatro Juarez, Guanajuato’s grandest theater. Inaugurated by dictator Porfirio Diaz in 1903, it is a splendid example of the excesses of the colonial era. The plush Moorish-inspired interior is superbly crafted in the art-nouveau style; the lobby and bar are made of carved wood inlaid with gold and silver. The exterior is adorned with statues and columns and the outside steps provide a perfect venue for watching the goings-on in the plaza while I enjoy a burrito bought from a street vendor.

My next destination is the most famous, and strangest, of Guanajuato’s many fine museums. Located on the western edge of town, the Museo de las Momias verifies Mexico’s unique obsession with death. In 1865 bodies were excavated from the local cemetery to make room for more recent arrivals. They discovered not skeletons, but grisly, mummified bodies with hideous facial expressions. The mineral-rich soil and the dry atmosphere had preserved the bodies in this manner. Today over 100 bodies are on display in glass cases, including child mummies dressed up like dolls, pregnant mummies, and a mummified fetus proudly displayed as “the smallest mummy in the world.” The place feels a little too morbid so I leave after only a few minutes.

My next destination is the most famous, and strangest, of Guanajuato’s many fine museums. Located on the western edge of town, the Museo de las Momias verifies Mexico’s unique obsession with death. In 1865 bodies were excavated from the local cemetery to make room for more recent arrivals. They discovered not skeletons, but grisly, mummified bodies with hideous facial expressions. The mineral-rich soil and the dry atmosphere had preserved the bodies in this manner. Today over 100 bodies are on display in glass cases, including child mummies dressed up like dolls, pregnant mummies, and a mummified fetus proudly displayed as “the smallest mummy in the world.” The place feels a little too morbid so I leave after only a few minutes.

My mummy encounter has extinguished any desire for more sightseeing so I return to my hotel. After a quick siesta I set out to explore Guanajuato at night.

The Jardin is even livelier than before. A mariachi band has replaced the jazz combo people are dancing to the pulsing rhythm. I dine at the Truco 7, a dimly lit bistro up a narrow side street. The dark wood décor, the background classical music, and the clientele, a mixture of travelers and students, combine to give the place a hip, intimate atmosphere. Best of all is the collection of antique radios on display. My beef burrito and black bean soup are delicious and filling, at CDN$7, including a cerveza, excellent value.

After dinner I taxi to Bar Fly, on the southern edge of town. The dark, trendy bar swarms with more students and gringos, who give the place a bohemian vibe. Pounding music alternates between reggae, ska, and rock. I start out quaffing beer but soon wade into the tequila. After all, this is Mexico. After three hours of dancing and tequila shooters I stagger down the road to my waiting bed reflecting on all I had experienced that day. While all of the tourist attractions I visited today were worth seeing, it is the charm of the town itself that leaves the most lasting impression. My favourite part of the day was getting lost in Guanajuato’s labyrinth of charming side streets and callejones. I can’t wait to get up tomorrow and do it again.

If You Go:

Getting There:

Guanajuato is 30 km. east of the Aeropuerto Internacional del Bajio, which is served by several domestic and international airlines. By bus from Mexico City, 4 ½ hrs. Deluxe coach and first-class buses leave Mexico City’s Terminal Norte approximately every hour.

Tour of Guanajuato from San Miguel de Allende

Performing Arts:

Aside from the Teatro Juarez, Guanajuato has two other theaters close to the Jardin de la Union, The Teatro Principal and the Teatro Cervantes. All three hold concerts and stage plays on a regular basis. Check their posters to see what’s on. The Teatro Principal and the Teatro Cervantes also screen international films.

Every weekend from March to September, the Viva la Magia program offers a range of arts and literary events hosted by Guanajuato’s theaters. The tourist office has a program schedule.

Started by students in the 1950s to commemorate Mexican writer Miguel Cervantes, the Festival Internacional Cervantinos has grown to become one of Latin America’s premier arts extravaganzas. Arts patrons come from around the world to perform music, dance, and theater for two to three weeks beginning the second week of October. Event tickets range in price from $11 to $48 Canadian and, along with accommodations, should be booked well in advance.

About the author:

Rick Neal is a free-lance writer who lives in Vancouver, Canada. He writes short fiction and travel stories. He’s traveled to China, Mexico, Central America, Turkey, and Europe. His dream is to someday write the great Canadian novel. Contact: richardneal91@hotmail.com

Photo credits:

First Guanajuato photo by Salvador Navarro Maldonado from Pixabay

El Pípila Monument: Ralibreros112 / CC BY-SA

All other photos are by Rick Neal