Papua New Guinea

by Jessica Carter

It was as if we were floating among the stars. They sparkled above me in the sky, and gleamed alongside me in the deep black water. All we could hear was the ringing siren of cicadas, and the only hint of earthliness was the occasional campfire light flickering through the jungle. It was 4am, and we were traveling by dug-out canoe down the mighty Sepik River of Papua New Guinea. I had to pinch myself to be sure that it was real.

The journey had started four days earlier, in the Middle Sepik village of Pagwi, one of just two points on the river that can be reached by road. The Sepik River snakes its way through the northwest of PNG across 1126 kilometers. Like its formidable brethren the Amazon and the Congo, it is shrouded in myth, and holds incredible spiritual and artistic significance to its inhabitants. One local legend says that the river’s age and strength are so great that no stone can be found within 50 kilometers of its banks.

The journey had started four days earlier, in the Middle Sepik village of Pagwi, one of just two points on the river that can be reached by road. The Sepik River snakes its way through the northwest of PNG across 1126 kilometers. Like its formidable brethren the Amazon and the Congo, it is shrouded in myth, and holds incredible spiritual and artistic significance to its inhabitants. One local legend says that the river’s age and strength are so great that no stone can be found within 50 kilometers of its banks.

My mother and her father, who both lived in PNG for many years, had also told me tales of the Sepik that seemed to rival even the greatest adventure stories – their descriptions of crocodile and piranha infested waters, floating villages and haunted spirit houses all sounded like they belonged in a Rudyard Kipling book. Today, there are less crocodiles, but not much else has changed.

I began my introduction to life on the Sepik in the tiny village of Palembei, home to 200 people and one of the river’s best-preserved ‘Haus Tambaran’. In Tok Pisin, a form of Pidgin English spoken in all but the most remote areas of PNG, Haus Tambaran means spirit house. Traditionally reserved for men, the large wooden structure serves a social and spiritual role for the tribe. Foreign women are allowed to enter as tourists, but local women cannot.

The Haus Tambaran we visited was an impressive hut, built on stilts, but enclosed almost to the ground. Taking off our hats and leaving our bags, we entered to find groups of men seated around smoldering fires. Choking in the smoke as we climbed the wooden ladder to the next level, we were greeted by more men and high ceilings decorated with hundreds of carefully carved artifacts.

The Haus Tambaran we visited was an impressive hut, built on stilts, but enclosed almost to the ground. Taking off our hats and leaving our bags, we entered to find groups of men seated around smoldering fires. Choking in the smoke as we climbed the wooden ladder to the next level, we were greeted by more men and high ceilings decorated with hundreds of carefully carved artifacts.

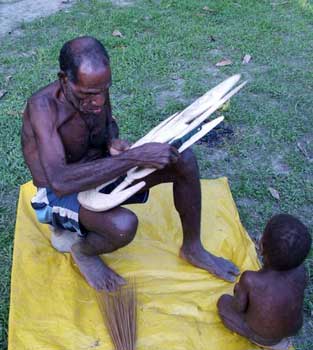

The totem animal of Palembei is the crocodile, and men still practice some of their traditional customs to show respect towards the creature. As we moved into the dimly lit areas of the Haus Tambaran, I could see that the upper-half of the men’s bodies were covered in perfectly formed crocodile scales. In the heady air of the hut, surrounded by the gazing masks of their ancestors, it was an eerie and intense moment that still feels more like a dream than a memory.

At the age of 15, the boys of the tribe spend a month living in the Haus Tambaran while they are initiated through scarification of the skin to form the scales. The scars are made with razor blades and packed with mud to prevent bleeding and infection. As missionaries move further up the river, less tribes continue to participate in initiations such as these, but in Palembei the young men are proud to show off their affinity with the crocodile through their body art.

That night we stayed in a neighbouring village, about 30 minutes by canoe from Palembei. Sticky from the day’s heat, we jumped into the cloudy brown water of the Sepik and did our best to avoid thinking about what might be lurking in the water with us. Toes and fingers still intact, we shared a meal of rice and barramundi with the Chief of the village. Once the sun disappeared, so did the villagers, and within hours the songs of the river and rain forest had engulfed us and the flimsy bark floorboards we slept on.

That night we stayed in a neighbouring village, about 30 minutes by canoe from Palembei. Sticky from the day’s heat, we jumped into the cloudy brown water of the Sepik and did our best to avoid thinking about what might be lurking in the water with us. Toes and fingers still intact, we shared a meal of rice and barramundi with the Chief of the village. Once the sun disappeared, so did the villagers, and within hours the songs of the river and rain forest had engulfed us and the flimsy bark floorboards we slept on.

I traveled with four members of my family and two local guides, Johannes and Jeffrey, who met us in Wewak, the regional centre of the East Sepik. Having guides meant that we could stay in villages like Palembei because PNG is governed by ‘wantok’, a social system that dictates that people of the same tribe must help each other. As long as we slept in villages where Johannes or Jeffrey had family or tribal connections, we were welcome.

Of course, PNG is not known as the land of the unexpected for nothing, and it wasn’t long before our careful plans drifted downstream. On our second day, we entered the Wasui Lagoon, a spectacular section of the Upper Sepik. As we traveled across the water, a group of black clouds grew across the sky. We were moving slowly and it was still several hours until dusk, when we would reach our hosts for the night. Nervous about the coming storm, our guides began tightening the ropes on the tarps while we prepared our ponchos. But once the rain started it was clear we didn’t stand a chance – each raindrop was a fistful splash of water. It seemed we had no choice but to stop at the nearest village.

Of course, PNG is not known as the land of the unexpected for nothing, and it wasn’t long before our careful plans drifted downstream. On our second day, we entered the Wasui Lagoon, a spectacular section of the Upper Sepik. As we traveled across the water, a group of black clouds grew across the sky. We were moving slowly and it was still several hours until dusk, when we would reach our hosts for the night. Nervous about the coming storm, our guides began tightening the ropes on the tarps while we prepared our ponchos. But once the rain started it was clear we didn’t stand a chance – each raindrop was a fistful splash of water. It seemed we had no choice but to stop at the nearest village.

We were also nervous about stopping, because neither Johannes or Jeffrey knew any people in the closest village. We took a chance and disembarked from the canoe, watching the huddle of 20 villagers smoking the fish they’d caught earlier that day. But with laughter as our only form of mutual communication, we found a welcoming place to wait out the storm. We spent the next two hours sitting under the village’s solitary hut, watching the wind and rain take on the lake while sharing slices of fresh coconut.

Sitting on a canoe and watching the world from the waterline became a daily meditation, and minutes and hours were almost interchangeable. The river is the vein of all life in the region, and in just one canoe trip we could have seen naked children swimming, men fishing silently for piranha, or women making sago with river water. Early one morning, we even saw the elusive Bird of Paradise on the outskirts of Wagu.

You can visit the Sepik River at any time of year, but the wet season is when mosquitoes are at their most vicious. Visit in January or June (at the end and beginning of the dry season) to experience the scenic extremes of seeing the river at its lowest and highest points, and make the most of the fewer insects. If you’re looking for a little luxury, you can take cruises through the Lower and Middle Sepik, but these trips won’t be able to access all of the smaller villages or tributaries. Traveling by canoe is surprisingly comfortable and other than a few short treks, limited fitness is required. All that is required is that you’re prepared for anything, and ready to be amazed.

5-Day Rabaul Mask Festival in Papua New Guinea with Meals

If You Go:

International flights to Port Moresby arrive directly from several cities in Australia, as well as some cities in Asia, including Singapore, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur and Manila. Visas can be obtained on arrival at Port Moresby Jacksons International airport, but avoid the queues and stress by organizing one in advance.

Currency is the Kina, worth US $1.00 = $2.56. Don’t be fooled into thinking that PNG is a cheap holiday destination! The lack of tourism infrastructure along with the growing expatriate population of wealthy miners means that transport, accommodation and food can be very pricey.

Don’t forget to take malaria tablets, mosquito repellent, long-sleeved shirts and trousers, and plenty of sunscreen. A sarong is extremely handy for women or men – it can serve as sun protection during the day and offer warmth in the cooler evening or early morning.

Visit the Papua New Guinea official tourism website.

Contact East Sepik Cultural Affairs by phone, +675 856 1108, or Niugini Holidays by email, info@ngholidays.com. Both offer expert advice and assistance for planning a trip to PNG, particularly in the Sepik region. It is worth considering to enlist the help of a travel agent because PNG can be a difficult place to navigate without careful preparation.

About the author:

Jessica Carter is a freelance journalist, originally from Australia. She is passionate about discovering new places and learning from new people. Her travels have led her to some amazing spots, ranging from the chaos of India to the scenic wonders of Alaska. Read about her current travels on her blog, Red Shoes and Cobblestones. Or read more of her articles by visiting her portfolio on jessicacarter.wordpress.com

Photo credits:

Top photo of Mount Hagen mudmen by Trevor Cole on Unsplash

All other photos by Jessica Carter.

Land of the Unexpected

Land of the Unexpected