by Marc Latham

When shrouded in mist, the Scottish Highlands evoke an image of living history, aging in slow motion, traveling forward with its past preserved by its traditionally wet cold weather, like ancient history preserved in a peat bog. The historic setting for a comfortable Urquhart Coaches domestic holiday inspired contrasting memories of my youthful world traveling, including previous trips to Scotland.

Travelling the Historic Mind

I remembered seeing tourists like I now was visit sights for a short time, while I spent all day there. They were the ‘other’ then, but I was one of them now. I didn’t feel a yearning for youthful freedom on the holiday; maybe because I’ve already experienced it, and it now seemed less interesting than the new experience of traveling with an older group of people.

Maybe it was the type of holiday: endless hot sunshine highways and beaches might have inspired a desire for more freedom. We were traveling to the end of the road on this holiday, literally at John O’ Groats, and to the most interesting places around, so I was content… although the Orkney Islands looked temptingly close out in the ocean!

Maybe it was the type of holiday: endless hot sunshine highways and beaches might have inspired a desire for more freedom. We were traveling to the end of the road on this holiday, literally at John O’ Groats, and to the most interesting places around, so I was content… although the Orkney Islands looked temptingly close out in the ocean!

Or maybe it was just nice to be one of the youngest of the group, rather than one of the oldest. Whatever the reasons, I thoroughly enjoyed the experience, and found it an ideal mix of travel, comfort and sights for a relaxing break on the road. I loved the quiet order, with everybody returning to their seats, and trying to be punctual.

Scottish Lowlands to Highlands

After passing Gretna Green on the border, famous for illicit romantic weddings, we stopped for a break in Moffat at a woolen and traditional goods shop. I was traveling with my mother and we walked up to the top of town, past the Star, which has been included in the Guinness Book of Records as the narrowest pub in the world. We had an ice-cream each from a delightful bakery opposite the pub. On the return journey we had a delicious lunch meal and ale in the pub.

Traveling north from Moffat we could soon see Stirling Castle perched on Castle Hill crag to our right. I remembered my previous trip to the Highlands, traveling on a regular coach service, and how Stirling Castle had signaled the border between the lowlands and highlands. That time I continued west to Fort William, passing through Glen Coe, which I remembered as particularly beautiful; with low cloud sifting through the high peaks hauntingly poignant. On that route we also traveled alongside a couple of long lochs, which were much longer and more spectacular than I’d imagined.

This time we traveled through the Cairngorms National Park and past Inverness to the small village of Garve. Low cloud and dusk limited the view, but increased the melancholic atmosphere; it felt great to be surrounded by nature once more, having escaped high-density population. The roads were so narrow in places there was little room for pedestrians or cyclists.

We arrived late at the Garve Hotel, but they had prepared dinner for when we’d unpacked. We were assigned rooms, and had our luggage transferred to them. We chose dinner tables in the conservatory section of the dining-room, alongside a garden, and kept them for the duration of our stay. Dinner was a three-course meal, with a few choices for each. Breakfast was included as well, and there was quality local entertainment all four nights.

Our driver/guide chose our day-trips schedule with regard to the weather forecast and distance: the longest countryside trip, to John O’ Groats, would be on the middle day, which was also forecast to be dry; the shorter countryside trip, to Skye, the next day, which was forecast to be dry in the afternoon. The last day was forecast to be the wettest, so Inverness was scheduled for then; it had more shelter and was also the shortest trip, before the long return journey south.

The Day Trips

It was raining heavily in the morning as forecast, and the mountains were under low cloud as we drove west alongside Loch Luichart and Loch Carron. However, by the time we crossed the bridge onto the Isle of Skye, after a short break in Kyle of Lochalsh on the mainland, there was mainly blue sky and sunshine. We traveled up the east coast of the largest Inner Hebrides island as far as Portree, where we stopped for lunch.

After a quick walk around the main town my mother and I went to the Isles Inn. It looked a traditional pub from the outside, and its interior was similarly rustic, with a stone decor ideal for the open fireplace. I had a tasty vegetarian haggis with mashed potatoes, vegetables and gravy to eat; washed down with a local ale.

After a quick walk around the main town my mother and I went to the Isles Inn. It looked a traditional pub from the outside, and its interior was similarly rustic, with a stone decor ideal for the open fireplace. I had a tasty vegetarian haggis with mashed potatoes, vegetables and gravy to eat; washed down with a local ale.

We had time to find the pier area, which reminded me of renowned Tobermory harbour on the Isle of Mull, with different coloured houses rising up the hill above. The name Portree is thought to derive from the Scottish Gaelic Port Ruighe, meaning “sloping harbour.” The neighbouring island of Raasay is visible to the east.

On the return journey there was time for a couple of photo stops on Skye, and we also popped down to Eilean Donan castle [PHOTO AT TOP] on the mainland. Late afternoon sun lit the castle, providing excellent light for photos. Eilean Donan dates from the thirteenth century, and was home to the Mackenzie Clan for most of its history. It was used as a location in movies such as Bonnie Prince Charlie (1948), Highlander (1986) and The World is Not Enough (1999).

It was top of my mother’s Scottish must-see list, without knowing where it was, after the BBC used its image as a link between programs. I’d walked from Eilean Donan to Kyleakin on Skye in 2004, after busing to the castle from Fort William. It was nice to have that memory, but nice to re-board the bus! The lochside peaks were visible approaching Garve, providing a contrasting view from the morning.

Driving north to John O’ Groats alongside the east coast was quite exhilarating. We stopped in Dornoch on the way, with its historic monthly market taking place that morning. On the opposite side of the street, the old jailhouse has been converted into stylish shops. It also has a thirteenth-century cathedral; Madonna and Guy Ritchie’s son Rocco John Ritchie was baptized there in 2000, the day before the couple married in nearby Skibo Castle.

Driving north to John O’ Groats alongside the east coast was quite exhilarating. We stopped in Dornoch on the way, with its historic monthly market taking place that morning. On the opposite side of the street, the old jailhouse has been converted into stylish shops. It also has a thirteenth-century cathedral; Madonna and Guy Ritchie’s son Rocco John Ritchie was baptized there in 2000, the day before the couple married in nearby Skibo Castle.

Dornoch is on the border of the Dornoch Firth and Moray Firth, and the sea views widened as we traveled north into the Highlands wilderness. Our driver/guide pointed out seals basking on a golden beach, and oil-rig platforms being built and transported out to the North Sea. After arriving at John O’ Groats I was pleasantly surprised that the Orkney Islands were clearly visible to the north. A local shop owner boarded the bus to tell us the names of biggest islands.

After taking our turn for the almost obligatory photo under the ‘distances’ sign I walked up the beach a little, looking for a quiet moment to reflect on where I was, and what might have passed over the land and water before, with the Orkneys home to prehistoric monuments comparable with Stonehenge. Recent archaeological research on the islands featured in a television documentary series has pushed the building of the stone megaliths on the island back to 5500 years ago; much earlier than current estimates for Stonehenge; suggesting the culture started in the north and traveled south.

The majority of our group had said they’d prefer to split the third day by visiting Loch Ness before Inverness, instead of spending the whole day in the latter, and that was okay with our driver/guide. So, in the morning we drove forty-five minutes south to Loch Ness, and parked above, funnily enough, Urquhart Castle. Nobody saw Nessie, but it was a nice setting above the loch. I had previously seen the north of the loch from the Rockness festival in 2008.

The majority of our group had said they’d prefer to split the third day by visiting Loch Ness before Inverness, instead of spending the whole day in the latter, and that was okay with our driver/guide. So, in the morning we drove forty-five minutes south to Loch Ness, and parked above, funnily enough, Urquhart Castle. Nobody saw Nessie, but it was a nice setting above the loch. I had previously seen the north of the loch from the Rockness festival in 2008.

In the afternoon we had a few hours in Inverness. After walking through the indoor market we had a nice pub lunch in Lauders bar. Then we walked north along the River Ness from Inverness Castle, with several historic buildings and churches lining the route. Moreover, the July-snow-capped peaks of Ben Wyvis and Little Wyvis created a picturesque horizon; as if symbolising the icing on the cake of our holiday.

There weren’t many people at the final night’s show, as many were preparing for the early start and return journey. However, everybody was upbeat in the morning, and on the return journey; I was surprised at the evident happy energy and enthusiasm on board after five days full of traveling long distances and busy sightseeing.

If You Go:

Links:

David Urquhart Travel

Garve Hotel, Wester Ross

The Isle of Skye

John O’Groats Visitor Guide

Inverness Information

About the author:

Marc Latham traveled to all the populated continents during his twenties. He studied during his thirties, including a BA in History, and spent his forties creative writing. He lives in Leeds, writing from the Travel 25 Years website. He has had a Magnificent Seven books published, most recently completing a trilogy of comedy fantasy travel by web maps and information. The blogged book’s theme might have inspired the return of the X Files. The Truth is Out There and all that, and the books are available on Amazon and other bookstores.

All Photos by Marc Latham

Eilean Donan

Skye Bridge

Skye Pub

John O’ Groats

Urquhart Castle

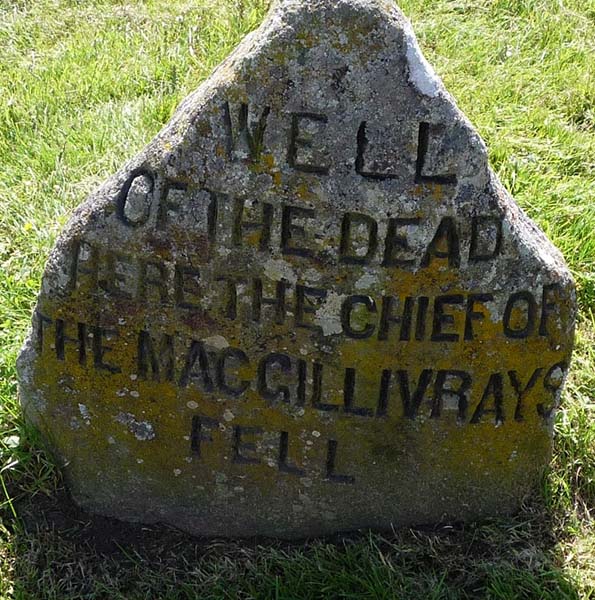

Since 2007, there has been a Visitor Center at the site which tells the tale. The Visitor Center is well worth your time to go through and learn all about the battle before heading outdoors to the moor itself. You can take an audio tape out with you which gives details about the battle and armies, a good choice. If you have the stomach, experience the circular video re-enactment of the battle inside the center. It is easy to feel respect and admiration, as well as heartache, for the doomed men who battled bravely, knowing they were charging into their death.

Since 2007, there has been a Visitor Center at the site which tells the tale. The Visitor Center is well worth your time to go through and learn all about the battle before heading outdoors to the moor itself. You can take an audio tape out with you which gives details about the battle and armies, a good choice. If you have the stomach, experience the circular video re-enactment of the battle inside the center. It is easy to feel respect and admiration, as well as heartache, for the doomed men who battled bravely, knowing they were charging into their death.

by John Thomson

by John Thomson I’m in Glasgow visiting relatives, recalled to the city by blood ties and circumstance. Glasgow is Scotland’s largest city, a little shabby in parts I must admit, its once busy dockyards replaced by a shopping mall, an amusement centre and a transportation museum. Thankfully, many of Glasgow’s magnificent sandstone buildings remain intact, a reminder of its better days when the city was flush with pride and Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh was at the top of his game. The Mackintosh story, like the city itself, is a bittersweet tale of success, decline and ultimate redemption. Not familiar with the name? You’ll recognize his furniture. His straight, high-backed chairs are cultural icons often associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement and although I’m not a fan of his chairs – too rigid for me – I have to acknowledge their importance.

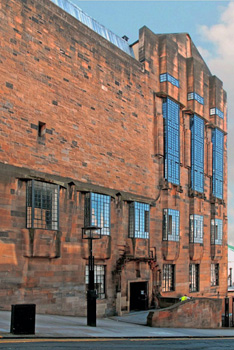

I’m in Glasgow visiting relatives, recalled to the city by blood ties and circumstance. Glasgow is Scotland’s largest city, a little shabby in parts I must admit, its once busy dockyards replaced by a shopping mall, an amusement centre and a transportation museum. Thankfully, many of Glasgow’s magnificent sandstone buildings remain intact, a reminder of its better days when the city was flush with pride and Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh was at the top of his game. The Mackintosh story, like the city itself, is a bittersweet tale of success, decline and ultimate redemption. Not familiar with the name? You’ll recognize his furniture. His straight, high-backed chairs are cultural icons often associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement and although I’m not a fan of his chairs – too rigid for me – I have to acknowledge their importance. I start my Glasgow tour on Sauchiehall (pronounced Sock-ee-hall) Street and work my way west. Glasgow converted its two main downtown thoroughfares, Buchanan and Sauchiehall Streets into pedestrian malls years ago and getting around the central core is a pedestrian’s dream. A gentle rain sprinkles the pavement but as soon as it starts, it stops. I’m barely wet. I climb Scott Street to the Glasgow School of Art considered the pinnacle of Mackintosh’s architectural career. Completed in 1909, it’s an imposing structure with a domineering command of its surroundings. It reminds me of a fortress. The western wall is tight and dense with narrow loopholes from which I imagine the inhabitants, if they were medieval archers, could shoot arrows if the city were under siege. The northern wall on the other hand has lots of large windows giving it an airy feel and letting in lots of light too. After all, this is an art school. Form follows function.

I start my Glasgow tour on Sauchiehall (pronounced Sock-ee-hall) Street and work my way west. Glasgow converted its two main downtown thoroughfares, Buchanan and Sauchiehall Streets into pedestrian malls years ago and getting around the central core is a pedestrian’s dream. A gentle rain sprinkles the pavement but as soon as it starts, it stops. I’m barely wet. I climb Scott Street to the Glasgow School of Art considered the pinnacle of Mackintosh’s architectural career. Completed in 1909, it’s an imposing structure with a domineering command of its surroundings. It reminds me of a fortress. The western wall is tight and dense with narrow loopholes from which I imagine the inhabitants, if they were medieval archers, could shoot arrows if the city were under siege. The northern wall on the other hand has lots of large windows giving it an airy feel and letting in lots of light too. After all, this is an art school. Form follows function.

Mackintosh was not only an architect but a designer too and the original Willow Tea Room on Sauchiehall is a prime example of his handiwork. Recruited by local businesswoman and teetotaller Catherine Cranston in 1896 to dress up her establishments, Mack designed everything – tables, chairs, room dividers, wall decorations, napkins and cutlery. The Tea Room, one of two in the city, has been preserved as a Mackintosh museum with the original stained glass door and replica furniture and yes, they still serve tea. Angularity is the prevailing theme – there are those high backed chairs again – and everything conforms to Mackintosh’s singular, unifying concept.

Mackintosh was not only an architect but a designer too and the original Willow Tea Room on Sauchiehall is a prime example of his handiwork. Recruited by local businesswoman and teetotaller Catherine Cranston in 1896 to dress up her establishments, Mack designed everything – tables, chairs, room dividers, wall decorations, napkins and cutlery. The Tea Room, one of two in the city, has been preserved as a Mackintosh museum with the original stained glass door and replica furniture and yes, they still serve tea. Angularity is the prevailing theme – there are those high backed chairs again – and everything conforms to Mackintosh’s singular, unifying concept. I get off at the Kelvinhall stop and walk to the Hunterian Art Gallery on the grounds of the University of Glasgow. Mack’s 1906 residence or at least parts of it – the hall, dining room, living room and the main bedroom – have been moved from their original location and reassembled here for public display. It’s breathtaking in its simplicity. Mackintosh and Margaret have designed everything themselves right down to the fireplace decorations. They even knocked down interior walls to create more space, a radical innovation at the turn of the nineteenth century. Sunlight bounces off the stark white walls accentuating the open plan. The angular motif that I first saw at the Willow Tea Room, lots of right angles and variations on the square, is repeated in the floor, the furniture and the wall decorations. Everything is co-ordinated. A bit too co-ordinated. I feel like I’m in a museum piece, which of course I am, and long for the remains of a half-eaten breakfast on the dining room table or a pile of dirty clothes at the foot of those oh-so-perfect matching beds. I wonder if Mack and his wife ever felt the same way. Probably not. I have to admit the duo were ahead of their time though. Their turn-of-the-century digs look like they belonged in the 1930’s.

I get off at the Kelvinhall stop and walk to the Hunterian Art Gallery on the grounds of the University of Glasgow. Mack’s 1906 residence or at least parts of it – the hall, dining room, living room and the main bedroom – have been moved from their original location and reassembled here for public display. It’s breathtaking in its simplicity. Mackintosh and Margaret have designed everything themselves right down to the fireplace decorations. They even knocked down interior walls to create more space, a radical innovation at the turn of the nineteenth century. Sunlight bounces off the stark white walls accentuating the open plan. The angular motif that I first saw at the Willow Tea Room, lots of right angles and variations on the square, is repeated in the floor, the furniture and the wall decorations. Everything is co-ordinated. A bit too co-ordinated. I feel like I’m in a museum piece, which of course I am, and long for the remains of a half-eaten breakfast on the dining room table or a pile of dirty clothes at the foot of those oh-so-perfect matching beds. I wonder if Mack and his wife ever felt the same way. Probably not. I have to admit the duo were ahead of their time though. Their turn-of-the-century digs look like they belonged in the 1930’s. I learn that young Mackintosh was quite the celebrity when he completed the Glasgow School of Art in 1909 but when he left his employers, Honeyman and Keppie, to strike out on his own, tastes changed and his business faltered. He and his wife Margaret retreated to London to concentrate on textile design. And when that didn’t pan out the couple eventually retired to southern France where Mackintosh renounced architecture entirely and spent the rest of his life painting watercolours.

I learn that young Mackintosh was quite the celebrity when he completed the Glasgow School of Art in 1909 but when he left his employers, Honeyman and Keppie, to strike out on his own, tastes changed and his business faltered. He and his wife Margaret retreated to London to concentrate on textile design. And when that didn’t pan out the couple eventually retired to southern France where Mackintosh renounced architecture entirely and spent the rest of his life painting watercolours.

As I board the plane to return home, I ponder the Mackintosh phenomenon. Yes, his buildings are stunning. Built to withstand the Scottish climate, they’re solid, substantial structures in contrast to those flouncy neo-classical buildings in vogue at the time. Scholars have called the style Scottish Baronial, tying Mackintosh and his ideas to the Scottish Renaissance of the early twentieth century when there was a creative surge in Scottish arts and letters. Perhaps he deserves his fame because he stripped away superfluous decoration in favour of detail that complemented the building’s integrity, paving the way for Modernism. Perhaps it’s because he involved himself in total design – integrating architecture with wall treatments, light fixtures and furniture. Mack pre-dated future “starchitects” like Frank Gehry by decades. Perhaps it’s all of these things, a combination of accomplishments both historic and aesthetic.

As I board the plane to return home, I ponder the Mackintosh phenomenon. Yes, his buildings are stunning. Built to withstand the Scottish climate, they’re solid, substantial structures in contrast to those flouncy neo-classical buildings in vogue at the time. Scholars have called the style Scottish Baronial, tying Mackintosh and his ideas to the Scottish Renaissance of the early twentieth century when there was a creative surge in Scottish arts and letters. Perhaps he deserves his fame because he stripped away superfluous decoration in favour of detail that complemented the building’s integrity, paving the way for Modernism. Perhaps it’s because he involved himself in total design – integrating architecture with wall treatments, light fixtures and furniture. Mack pre-dated future “starchitects” like Frank Gehry by decades. Perhaps it’s all of these things, a combination of accomplishments both historic and aesthetic.

Anticipation slowly rose as I traversed each room, stopping to read every detail about this holy book and its convoluted history. Entering the dimly lit Treasury Room at the end of the hall, I discovered four books displayed inside a glass case. The Book of Kells, divided into two tomes, was accompanied by the Book of Durrow and the Book of Armagh. Clearly the jewel in the crown was the four Gospels assembled into the Book of Kells.

Anticipation slowly rose as I traversed each room, stopping to read every detail about this holy book and its convoluted history. Entering the dimly lit Treasury Room at the end of the hall, I discovered four books displayed inside a glass case. The Book of Kells, divided into two tomes, was accompanied by the Book of Durrow and the Book of Armagh. Clearly the jewel in the crown was the four Gospels assembled into the Book of Kells.

A chilly wind and a gray overcast sky greeted Diane and me as we set foot on Iona, the birthplace of Christianity in Scotland. St Columba (Colmcille) and twelve companions founded the first monastery here in 563 CE. Almost nothing remains of that original settlement because it had been replaced by St. Mary’s Cathedral, a Benedictine abbey church dating to 1200 CE. You might be surprised to find that this is a working abbey today, operated by an ecumenical community known as the Iona Commonwealth.

A chilly wind and a gray overcast sky greeted Diane and me as we set foot on Iona, the birthplace of Christianity in Scotland. St Columba (Colmcille) and twelve companions founded the first monastery here in 563 CE. Almost nothing remains of that original settlement because it had been replaced by St. Mary’s Cathedral, a Benedictine abbey church dating to 1200 CE. You might be surprised to find that this is a working abbey today, operated by an ecumenical community known as the Iona Commonwealth. A short distance in front of St. Columba’s Shrine, you find St. John’s Cross. This is a copy of an 8th century high cross displayed in the nearby Monks’ Infirmary now serving as a museum. The original cross was painstakingly reconstructed from fragments found on site. Another item of note in the museum is St. Columba’s Pillow, a stone with a ringed cross carved into it. This treasure is stored inside a small metal cage. There is no proof that the saint’s head ever rested on this pillow however.

A short distance in front of St. Columba’s Shrine, you find St. John’s Cross. This is a copy of an 8th century high cross displayed in the nearby Monks’ Infirmary now serving as a museum. The original cross was painstakingly reconstructed from fragments found on site. Another item of note in the museum is St. Columba’s Pillow, a stone with a ringed cross carved into it. This treasure is stored inside a small metal cage. There is no proof that the saint’s head ever rested on this pillow however. It was déjà vu all over again; a chilly wind and a gray overcast sky greeted Diane and me at St. Columba’s Church in Kells. This church, set on the site of the original Monastery of Kells, dates to 1778. The churchyard also contains a number of high crosses and a 26-meter round tower all dating back to the early monastic period and the arrival of the Book of Kells.

It was déjà vu all over again; a chilly wind and a gray overcast sky greeted Diane and me at St. Columba’s Church in Kells. This church, set on the site of the original Monastery of Kells, dates to 1778. The churchyard also contains a number of high crosses and a 26-meter round tower all dating back to the early monastic period and the arrival of the Book of Kells. Learning their lesson, the monks constructed St. Colmcille’s House across the street from the present day churchyard as a more secure location for their precious manuscript and the relics of St. Columba. This dimly lit, empty stone building served as a monk’s dwelling and a scriptorium. The monk’s sleeping quarters in the loft above is still accessible by ladder.

Learning their lesson, the monks constructed St. Colmcille’s House across the street from the present day churchyard as a more secure location for their precious manuscript and the relics of St. Columba. This dimly lit, empty stone building served as a monk’s dwelling and a scriptorium. The monk’s sleeping quarters in the loft above is still accessible by ladder.

London it isn’t – nor Edinburgh. There’s nothing twee, contrived, touristy or pretty-pretty about Glasgow. Glasgow is down-to-earth, has real character. It’s smart, gritty, witty, vibrant and alive. It’s the genuine article.

London it isn’t – nor Edinburgh. There’s nothing twee, contrived, touristy or pretty-pretty about Glasgow. Glasgow is down-to-earth, has real character. It’s smart, gritty, witty, vibrant and alive. It’s the genuine article. The Necropolis lies on a hill overlooking the city. All of Glasgow stretched out before us: the Tennent’s brewery close by, isolated tenement blocks, smaller brick-built houses, concrete offices and wind turbines on the moors, far on the horizon. Alan pointed out the place where his tenement home had once stood, long gone now. It had survived an incendiary bomb during the war (His mother, an ARP warden, had hosed down the fire in the attic herself) only for the building to be later demolished.

The Necropolis lies on a hill overlooking the city. All of Glasgow stretched out before us: the Tennent’s brewery close by, isolated tenement blocks, smaller brick-built houses, concrete offices and wind turbines on the moors, far on the horizon. Alan pointed out the place where his tenement home had once stood, long gone now. It had survived an incendiary bomb during the war (His mother, an ARP warden, had hosed down the fire in the attic herself) only for the building to be later demolished. The gravestones are filled with story and history. I could have spent hours there uncovering lives like John Ronald Ker’s: accidentally drowned while shooting wildfowl from a small boat off Contyre of Ronaghan at the early age of 21 – of a generous and amiable disposition and endearing qualities which made him so agreeable a companion, so good and true a friend. (July 1868)

The gravestones are filled with story and history. I could have spent hours there uncovering lives like John Ronald Ker’s: accidentally drowned while shooting wildfowl from a small boat off Contyre of Ronaghan at the early age of 21 – of a generous and amiable disposition and endearing qualities which made him so agreeable a companion, so good and true a friend. (July 1868)

A stained glass tells the story of St Mungo and the miracles associated with him (symbols that form the Glasgow coat of arms):

A stained glass tells the story of St Mungo and the miracles associated with him (symbols that form the Glasgow coat of arms): “I know,” said Alan. “It’s a mistake. Charlie took great delight in showing people his name on the memorial, claiming he was one of the living dead. He thought it a great joke.” “But how did he end up on the list?”

“I know,” said Alan. “It’s a mistake. Charlie took great delight in showing people his name on the memorial, claiming he was one of the living dead. He thought it a great joke.” “But how did he end up on the list?” We visited the Clydeside, currently being regenerated with its smart new Riverside Museum, a theatre – the Armadillo, and the science museum tower. Over in the West End we discovered a vibrant hub of fine eateries, trendy boutiques and night clubs set among the cleaned-up sandstone Victorian buildings; handsome historic university buildings and museums set in leafy parks and hilly bluffs.

We visited the Clydeside, currently being regenerated with its smart new Riverside Museum, a theatre – the Armadillo, and the science museum tower. Over in the West End we discovered a vibrant hub of fine eateries, trendy boutiques and night clubs set among the cleaned-up sandstone Victorian buildings; handsome historic university buildings and museums set in leafy parks and hilly bluffs.