by Karin Leperi

If lewdness, lawlessness, and lynchings could define the character of a town in the days of the Old West, then Sidney, Nebraska easily earned the title of being one of the most wicked if not wretched towns on the Western frontier.

So why is a Nebraska burgh that most haven’t even heard about considered more deadly than Deadwood and Dodge City, more treacherous than Tombstone, more corrupt than Cheyenne, or more evil than El Paso? The story lies in the lurid history of salacious Sidney.

The first large group of settlers came to the great plains of Nebraska during the California Gold Rush during the years from 1848-1855. Then the Pony Express came through in 1860-1861, at nearby Mud Springs station, which subsequently served as a transcontinental telegraph station and a stage coach stop. (Sidney did not yet exist). In pursuit of a west coast terminus, the railroad arrived in 1867, the same year Nebraska became a state, even though this part of Nebraska was still considered Indian country. While the eastern part around Omaha was settled, the western plains around Sidney were sparsely populated.

Fort Sidney Births a Namesake Town

![Rose Street [now Center Ave] circa 1881](https://travelthruhistory.com/pix/nebraska2.jpg) To protect the Union Pacific Railroad and its workers from an increased frequency of Indian attacks, Fort Sidney (aka Sidney Barracks) was built in 1867 as a strategic place to safeguard interests of United States expansionism. (Fort Sidney was named after Sidney Dillon, a railroad attorney and president of the Union Pacific). By 1874, the Black Hills Gold Rush fever hit the Dakota territories, peaking in 1876-77. With gold as the lure, Sidney became the southern terminus for those traveling north to Deadwood in the late 1870s and 1880s, seeking their fortunes in the windswept Black Hills and sacred Native American territory.

To protect the Union Pacific Railroad and its workers from an increased frequency of Indian attacks, Fort Sidney (aka Sidney Barracks) was built in 1867 as a strategic place to safeguard interests of United States expansionism. (Fort Sidney was named after Sidney Dillon, a railroad attorney and president of the Union Pacific). By 1874, the Black Hills Gold Rush fever hit the Dakota territories, peaking in 1876-77. With gold as the lure, Sidney became the southern terminus for those traveling north to Deadwood in the late 1870s and 1880s, seeking their fortunes in the windswept Black Hills and sacred Native American territory.

One small detail was overlooked: the U.S. government had signed the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 which exempted the Black Hills from white settlement. This was effectively ignored once the gold rush began.

Gold Fever Brings an Unsavory Element

Sidney grew from a place with endless and empty Great Prairie views to a boomtown sprouting saloons and bordellos as quickly as the timber could be had. Of course, with easy money and loose women came outlaws. Sidney was no exception. From 1876-1881, the town had the notoriety of accumulating over 1,000 criminal cases along with 56 reported murders. Crooked town leaders often looked the other way on many cases that reputedly did not happen.

Sidney grew from a place with endless and empty Great Prairie views to a boomtown sprouting saloons and bordellos as quickly as the timber could be had. Of course, with easy money and loose women came outlaws. Sidney was no exception. From 1876-1881, the town had the notoriety of accumulating over 1,000 criminal cases along with 56 reported murders. Crooked town leaders often looked the other way on many cases that reputedly did not happen.

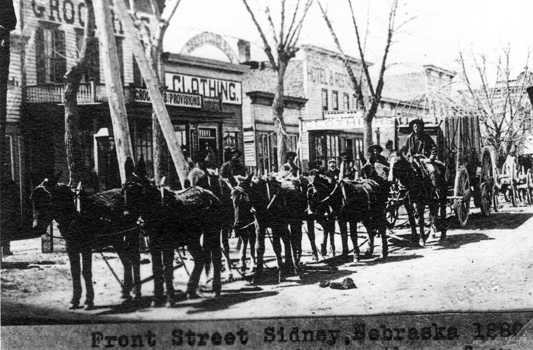

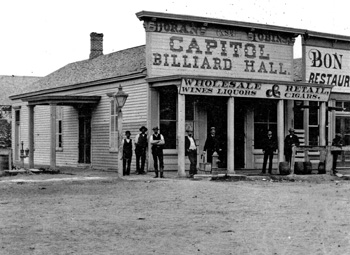

One recount has it that a single city block held 23 saloons, with as many as 80 saloons along Sidney’s Front Street, which ran parallel with the tracks of the Union Pacific Railroad. Numerous gaming halls, brothels and the world’s first 24-hour theater were billed attractions. It is said that almost 2,000 people circulated through town on any given day – some of them were gold seekers while others were looking to relieve fortunate souls of their riches.

Many a famous person made their way through Sidney in addition to gold miners, gunslingers, cattle rustlers, gamblers, prostitutes and God-fearing pioneers and homesteaders. The legendary likes of Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane, Doc Middleton, Buffalo Bill Cody, Butch Cassidy, Jesse James, and Susan B. Anthony found their way through this frontier town.

Many a famous person made their way through Sidney in addition to gold miners, gunslingers, cattle rustlers, gamblers, prostitutes and God-fearing pioneers and homesteaders. The legendary likes of Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane, Doc Middleton, Buffalo Bill Cody, Butch Cassidy, Jesse James, and Susan B. Anthony found their way through this frontier town.

Good people were warned to stay away, while those traveling by coach were explicitly told not to leave their coach while in Sidney, or to do so at their own risk. With lawlessness and lynchings everywhere in Sidney, the town was out of control. Legends flourished. In fact, one hanging that seemed tortured though it wasn’t intentional became the model to gunfighters as to why they should “Get out of Sidney.”

The Hanging that Went Terribly Wrong

The beginnings of what would be a ‘hanging-gone-all-wrong’ commenced with the largest gold robbery in the history of the United States. It was the year 1880 and as might be expected, it occurred in Sidney, involving the equivalent of a $5 million gold armed getaway. The repercussions of this unsolved heist (even today it remains a mystery) were so far reaching that the Union Pacific Railroad threatened to pull up stakes if the town didn’t clean up its tumultuous reputation.

The beginnings of what would be a ‘hanging-gone-all-wrong’ commenced with the largest gold robbery in the history of the United States. It was the year 1880 and as might be expected, it occurred in Sidney, involving the equivalent of a $5 million gold armed getaway. The repercussions of this unsolved heist (even today it remains a mystery) were so far reaching that the Union Pacific Railroad threatened to pull up stakes if the town didn’t clean up its tumultuous reputation.

Fearful of their livelihoods vanishing forever, a group of 64 businessmen and leading citizens were determined to change forever the future of their town. The vigilante group decided to roundup 16 of the most belligerent, badass crooks they could find within their city confines. The intention was that this unsavory group of thugs would be hung in town as an example to others of what happens when you go afoul of the law.

Fearful of their livelihoods vanishing forever, a group of 64 businessmen and leading citizens were determined to change forever the future of their town. The vigilante group decided to roundup 16 of the most belligerent, badass crooks they could find within their city confines. The intention was that this unsavory group of thugs would be hung in town as an example to others of what happens when you go afoul of the law.

On Saturday night, April 2, 1881, and for some unknown reason, the jailer acting as Sheriff assisted others in springing three of the more notorious crooks for a public lynching. The first selected was Watson Jack “Red” McDonald, who met his fate when a vigilante crew strung him up from a tree on Courthouse square. According to Gary Person, current city manager of Sidney, the hanging had severe glitches as the animated body of McDonald continued to contort and twitch in the pangs of a prolonged death, much to the anguish of public citizens. The agonizing and distasteful death left a sour note for many and word spread quickly through town and beyond about the gruesome hanging.

Get Out of Sidney or Else…

On April 5, 1881, the Cheyenne Daily Leader reported, “The mob led the way over to the Courthouse square, threw a rope over the branch of a tree, and then they proceeded to draw Red up. Red did beg for his life to no avail, but the mob did consent to place a handkerchief under the noose, so as not to hurt his neck. The mob had tied Red’s hands and feet, and simply lifted him from the ground, strangling him instead of breaking his neck. It was reported that the contortions of the body are described as horrible in the extreme. Red did not die for a full fifteen minutes.”

On April 5, 1881, the Cheyenne Daily Leader reported, “The mob led the way over to the Courthouse square, threw a rope over the branch of a tree, and then they proceeded to draw Red up. Red did beg for his life to no avail, but the mob did consent to place a handkerchief under the noose, so as not to hurt his neck. The mob had tied Red’s hands and feet, and simply lifted him from the ground, strangling him instead of breaking his neck. It was reported that the contortions of the body are described as horrible in the extreme. Red did not die for a full fifteen minutes.”

The next day the same group of businessman issued and posted a document that essentially warned varmints to “Get out of Sidney” or they would suffer the same fate as McDonald. It was directed to: “All murderers, thieves, pimps and slick-fingered gentlemen.”

The story goes that after the lynching and subsequent herding up of prostitutes for shipping out on the next train, that 200 people left Sidney before the April 22, 1881 deadline as stipulated in the decree. As author Loren Avey wrote in, Lynchings, Legends, & Lawlessness – the Story of Historical Sidney, Nebraska, “The population of Sidney decreased dramatically in a very short period of time.”

The story goes that after the lynching and subsequent herding up of prostitutes for shipping out on the next train, that 200 people left Sidney before the April 22, 1881 deadline as stipulated in the decree. As author Loren Avey wrote in, Lynchings, Legends, & Lawlessness – the Story of Historical Sidney, Nebraska, “The population of Sidney decreased dramatically in a very short period of time.”

Sidney was the first of any wild western community to deal with lawlessness on the frontier in an organized way. “This document served as an inspiration for similar documents in other towns ruled by crime and criminals,” according to Avey. He goes on to say that, “Sidney was held in high esteem by these other wild and lawless towns that also wanted to become civilized by this action of self-preservation.”

The Sidney model quickly inspired Kansas to borrow and interpolate the warning to, “Get out of Dodge” with similar effectiveness. Avey wrote that the reason Sidney didn’t get the claim for the phrase was because, “Saying ‘Get Out of Sidney’ probably doesn’t carry quite the same romantic terminology of the Old West, but the facts point out this is where the idea was born, the blue print was authored and implemented by 64 very brave legitimate businessmen in Sidney.”

If You Go:

Cabela’s World Headquarters – In 250,000 square feet of the flagship showroom, shop while admiring over 500 wildlife replicas in realistic wildlife displays throughout the store. The world’s foremost outfitter for outdoor adventures, they specialize in gear for hunting, fishing, boating, and camping.

Cabela’s World Headquarters – In 250,000 square feet of the flagship showroom, shop while admiring over 500 wildlife replicas in realistic wildlife displays throughout the store. The world’s foremost outfitter for outdoor adventures, they specialize in gear for hunting, fishing, boating, and camping.

Sidney Boot Hill Cemetery – A sundry of shady characters, victims, soldiers and even an Indian or two are buried here. Originally built in 1868 to bury soldiers killed in gun battle at nearby Fort Sidney, cemetery burials ceased in 1894. Be sure to check out the sculpture by Robert Summers at the top of the hill. “The Trail Boss” pays homage to the courageous men who came up the Texas Trail and the role that trail drives played in establishing the beef cattle industry in the northern plains.

The Sidney Pony Express Monument – The bronze statue of a pony express rider and his horse is a fitting tribute to one of the most dangerous occupations in the history of the West. Nebraska had more miles of trails than any of the other seven states where the pony express riders rode. This is the only national monument with a marker and flag for every state on the Pony Express route.

The Sidney Pony Express Monument – The bronze statue of a pony express rider and his horse is a fitting tribute to one of the most dangerous occupations in the history of the West. Nebraska had more miles of trails than any of the other seven states where the pony express riders rode. This is the only national monument with a marker and flag for every state on the Pony Express route.

Scotts Bluff National Monument – Located about 90 minutes drive northwest of Sidney, this monument is an important landmark on the historic Oregon Trail. Rising over 800 feet above the surrounding prairie, it was an iconic rock bluff that served as a famous navigation aide for fur traders, missionaries, pioneers, and the military in the 19th century.

Dude’s Steak House – Family-owned and operated and going into their 5th generation, this place is known for generous cuts of steaks and mouth-watering burgers.

Best Western Plus Sidney Lodge – Only minutes away from the famous Pony Express Monument and equally close to Cabela’s, this upscale lodge offers complimentary breakfast, gym, pool, and free wireless internet in all rooms.

About the author:

Karin Leperi is a multi award-winning writer and photographer with bylines in over 90 outlets – magazines, newspapers, radio, internet, and mobile media-based platforms. She is infatuated with crafting compelling stories and creating arresting images that immerse readers in culture, cuisine, cruising and travel. To her, It’s all about flavors, color, texture and dimension as well as contextual meaning. And it’s about chromatic purity, a freedom from dilution. To see more of her photos, go to: www.travelprism.com. You can contact her at: wurldtraveler@gmail.com

All photos are by Karin Leperi, or courtesy of the City of Sydney:

Front Street circa 1880 (City of Sidney)

Rose Street [now Center Ave] circa 1881 (City of Sidney)

Capital Billiard Saloon circa 1878 (City of Sidney)

Scotts Bluff with wagon train (Karin Leperi)

The Trail Boss sculputure in Boot Hill (Karin Leperi)

Reenactor with Scotts Bluff in background (Karin Leperi)

Steps leading up to Boot Hill (Karin Leperi)

Cabela’s interior wildlife display (Karin Leperi)

Cabela’s interior wildlife display (Karin Leperi)

Pony Express Monument in Sidney (Karin Leperi)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.