London, England

by Angela Kirkby

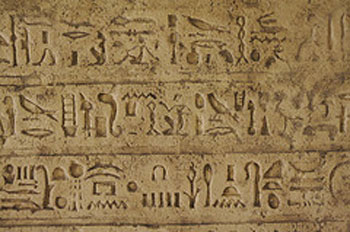

When I was a kid, I wanted to be an Egyptologist. I adored the mummy cases in the British Museum, bright gilt and the intensely saturated blue of lapis lazuli; the faces with their serious kohl-outlined eyes, the dreadlocked wigs and little fake beards. I loved the huge porphyry and granite statues of long dead kings. I wanted to dig up tombs, and climb pyramids, and read the Book of the Dead.

Well, that’s the British Museum for you. Lots of Egyptian bling and Pharaonic excess; but not, perhaps, much of a feel for the way most Egyptians lived their everyday lives. (Though there is a cute toy lion on wheels in one of the rooms, with a hinged jaw that would have gone up and down when a little Egyptian child pulled it across the floor.) To get the sand of Ancient Egypt right between your toes, you’ll need to visit the Petrie Museum.

Sir Flinders Petrie was the first professor of Egyptology in the UK, and is considered one of the founders of scientific archaeology. He was the first to use seriation as a means of dating Egyptian artifacts, and his excavations included work at Amarna, Tanis, and Abydos. He saw himself as ‘a salvage man’ – he’d been appalled by the destruction of ancient artifacts, and was concerned to save what he could.

Besides, he wasn’t just interested in the Pharoahs. When he excavated at Fayum, he was particularly interested in late Roman era burials, which had not been properly studied before, and it’s down to Petrie that we have such a fine collection of Fayum mummy-portraits. It was on this dig that he also found the Pharaonic tomb-builders’ village – evidence of working class Egyptian life. It’s his work, together with that of Amelia Edwards, who founded the chair of Egyptology at UCL and gave her own antiquities as the nucleus of the museum, that created the core of this collection.

I’ve been told that the Petrie museum contains 80,000 separate objects. I couldn’t begin to count them. But hold that number in your head and just think, if you had to collect 80,000 objects to represent your own life, what would you include? A Tetrapak of milk? An iPod? One of those coffee mugs with ‘Dad’ written on it, or perhaps a much loved fountain pen, or an old pair of trainers? You’d end up with a fascinating collection of bits and pieces – some bling, some fine art, some things that we find utterly boring but which, in 7,000 years’ time, will come to seem amazing and rare. 80,000 objects, 7,000 years old; these are huge numbers.

I’ve been told that the Petrie museum contains 80,000 separate objects. I couldn’t begin to count them. But hold that number in your head and just think, if you had to collect 80,000 objects to represent your own life, what would you include? A Tetrapak of milk? An iPod? One of those coffee mugs with ‘Dad’ written on it, or perhaps a much loved fountain pen, or an old pair of trainers? You’d end up with a fascinating collection of bits and pieces – some bling, some fine art, some things that we find utterly boring but which, in 7,000 years’ time, will come to seem amazing and rare. 80,000 objects, 7,000 years old; these are huge numbers.

And it’s true that as soon as you step into the museum, you’re overwhelmed by the sheer size of the collection. It’s piled up, heaped up, hugger-mugger, not displayed in that nice minimalist way modern museums seem to love.

But the thing that really amazes me in the Petrie is how quickly – despite those big numbers – you find a single object, and suddenly you can feel the past actually there with you. You can almost taste it, smell it, touch it. For instance, there’s a piece of linen dating from about 5,000 BC – one of the earliest textile remains ever found; its sheer age makes it precious. Or there’s something I find absolutely fascinating, an architectural drawing of a shrine that dates from 1300 BC; thin, faded lines on papyrus, yet it seems to me I can almost trace the way that scribe’s hand traveled over the surface.

There are pots and pans, there are ancient sandals and socks and hair curlers, there’s a horse harness and if the horse got sick, there’s a veterinary papyrus explaining how to heal various animal hurts – the only one of its type that still exists. There’s a gynecological papyrus, too, the oldest known – the ancient Egyptians might not have had Prozac or CAT scans, but their medical knowledge was more advanced than you might think.

There are pots and pans, there are ancient sandals and socks and hair curlers, there’s a horse harness and if the horse got sick, there’s a veterinary papyrus explaining how to heal various animal hurts – the only one of its type that still exists. There’s a gynecological papyrus, too, the oldest known – the ancient Egyptians might not have had Prozac or CAT scans, but their medical knowledge was more advanced than you might think.

There are things that look silly, like the gilded toe cover for a mummy from the early Roman period. Ordinary Egyptians couldn’t afford golden coffins, so they made them out of papier maché – or rather, cartonnage, textile wrappings with plaster laid on top. If you were reasonably well off you had an entire lid made out of cartonnage – if you weren’t, you got a mask, a breastplate, and yes, those toe-covers.

One of my favourite macabre displays anywhere sits in a corner; the four thousand year old skeleton sitting upright in a huge earthenware pot.

And there’s one exhibit that particularly appeals to me because of its amazing beauty – and because I want to wear it; a painstakingly reconstructed, calf-length beaded dress.

Unlike many collections, the Petrie Museum contains artifacts from every period of Egypt’s history. There are prehistoric mace heads, for instance, in gleaming polished stone. (Later, the mace became a ceremonial weapon, often decorated with scenes of the victorious Pharaoh. In prehistoric Egypt, though, it was still a functional weapon; even so, some of these pear-shaped or disk-shaped maces are of astonishing beauty.) From later Egypt come Coptic textiles, with bright colours and lively designs. The collection includes more recent artifacts from Islamic Egypt, and the museum has even started to amass a small selection of objects from the present day.

Unlike many collections, the Petrie Museum contains artifacts from every period of Egypt’s history. There are prehistoric mace heads, for instance, in gleaming polished stone. (Later, the mace became a ceremonial weapon, often decorated with scenes of the victorious Pharaoh. In prehistoric Egypt, though, it was still a functional weapon; even so, some of these pear-shaped or disk-shaped maces are of astonishing beauty.) From later Egypt come Coptic textiles, with bright colours and lively designs. The collection includes more recent artifacts from Islamic Egypt, and the museum has even started to amass a small selection of objects from the present day.

The Petrie museum isn’t just a space full of interesting objects. It’s a research collection, and it takes outreach very seriously, too. Recently, it’s been working with black and north African communities in London – the acquisition of modern artifacts partly stems from a desire to put Ancient Egypt in a modern perspective, and is one of the results of this programme. The Petrie museum has also taken part in LGBT history month for the past three years, with talks on alternative sexuality in ancient Greece and Egypt, and most recently with an LGBT ‘trail’ through the collection.

The museum hosts some really quirky events, too. For instance if you want to give yourself the shivers, you can attend a Hammer Horror film screening – starring, naturally, a malevolent Egyptian mummy. (I wish they’d show Carry On Cleo, though.) There are object handling seminars; one a little while ago gave attendees the chance to hold a two-thousand-year-old basket and work out how it had been woven. The title of a talk last year shows just how intimately archaeologists now know the people of ancient Egypt – “Pinch pots and nappy rash – early childhood at Lahun”.

The museum hosts some really quirky events, too. For instance if you want to give yourself the shivers, you can attend a Hammer Horror film screening – starring, naturally, a malevolent Egyptian mummy. (I wish they’d show Carry On Cleo, though.) There are object handling seminars; one a little while ago gave attendees the chance to hold a two-thousand-year-old basket and work out how it had been woven. The title of a talk last year shows just how intimately archaeologists now know the people of ancient Egypt – “Pinch pots and nappy rash – early childhood at Lahun”.

Or you can learn how to knit Coptic socks. (I’m not kidding.)

The whole collection – or at least, as much as the curators can manage to put on display – is crammed into just a couple of large rooms. The museum doesn’t look like much on the outside – apparently it was once a stable – and it won’t win prizes for interior décor, but it’s just stuffed with things, in stunning abundance. You don’t visit this museum so much as you explore it; staff will even give you a torch so that you can penetrate the dark recesses of some of the display cases.

That will change, I’m afraid; there are plans for a new museum to display the whole collection. But for the time being, if you want to pretend to be Indiana Jones in Raiders of the Lost Ankh (sorry!), this is the place to be!

Private Guided Tour of the British Museum in London

If You Go:

The Petrie Museum, University College London, Malet Place, London WC1E 6BT

Closed Sunday and Monday; Tuesday – Friday 13:00 – 19:00 and Saturday 11:00 – 14:00

About the author:

Andrea Kirkby has been traveling since the age of nine and has racked up four continents and over 30 countries. Having tired of a career in financial markets, she is now a full time writer and has less free time than ever.

Photo credits:

Petrie Museum exterior, both hieroglyphics and statues by Nic McPhee

Museum interior by Ann Wuyts

All photos are licensed under the Creative Commons ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.