This is the third of three articles by Lee Ruddin about slavery in Liverpool and a walking tour of the city where evidence of Black History can now be seen.

See part 1 at https://travelthruhistory.com/liverpool-black-history-walking-tour-part-1/

See part 2 at https://travelthruhistory.com/liverpool-black-history-walking-tour-part-2-of-3/

FROM ABELL’S MEMORIAL STONE TO THE INTERNATIONAL SLAVERY MUSEUM

After reading the inscription on Abell’s gravestone (from the vantage point of the photographer, as shown in Part 2), turn around 180 degrees and exit St. Nicholas Church Gardens through the way you entered, namely Tower Gardens, before turning left onto Water Street and taking the first right onto Drury Lane. The inter-war Grade II-listed India Buildings occupies the entire block, so will be on your left until the junction with Brunswick Street, a one-way road sloping downwards towards the River Mersey that bisects Drury Lane. This you must cross (continuing south-eastwards) to reach the Piazza Fountain, situated in a courtyard on your right-hand-side, 160 metres away. Known locally as the “Bucket Fountain”, Richard Huws’ Grade II-listed kinetic water sculpture (1967) endeavours to replicate – through the filling and spilling of 20 pivoting hoppers on seven vertical poles – the sound of waves crashing against the shore (Image below).

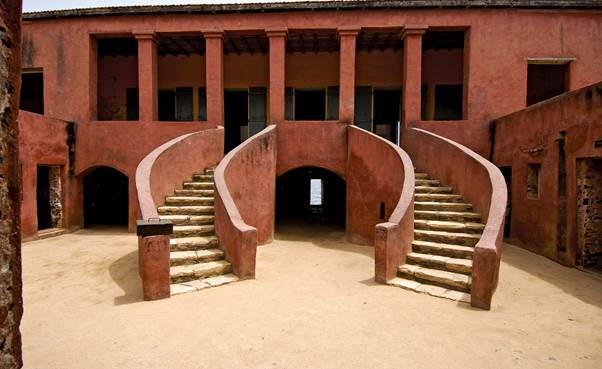

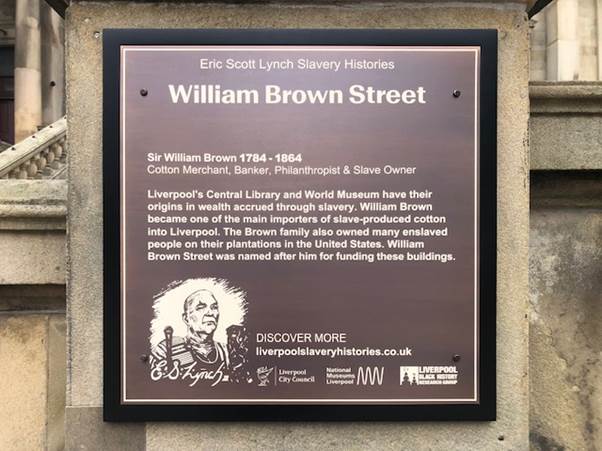

There’s no evidence that the Welsh designer intended it to serve as a memorial to slavery, although the stairwells do bear a striking resemblance to those of the House of Slaves on Gorée Island, a slave-trading post on the west coast of Africa (image below). Furthermore, an “African” shield-shaped plaque on one of the spiral-shaped, cantilevered viewing platforms refers to the site’s proximity to the late eighteenth-, rebuilt early nineteenth-century arcaded edifice known as Goree Warehouses and Piazza (Image 16). These, together with what’s arguably an implicit nod to the trade (Image 17), support the case against a developer seeking its relocation, especially since Laurence Westgaph – recipient of a Black History Month Achiever’s Award for highlighting the lesser-known local roots that sustained the more familiar global routes of the Transatlantic Slave Trade – asserts on one of his walking tours that it’s Liverpool’s ‘abstract and only attempt to memorialise slavery in the public realm’.

Address: Beetham Plaza, Drury Lane, Liverpool, L2 0XJ.

Return to where Drury Lane meets Brunswick Street and turn left, crossing The Strand and Goree dual carriageway at the traffic lights, before taking another left in front of George’s Dock Ventilation Tower (an imposing Grade II-listed Art Deco building), whereupon you continue in the same direction until you reach its south-east corner bordering Mann Island. It’s here – about ten feet up on the wall – that you will observe the street sign Goree, roughly 160 metres distant. This is the approximate location of the eponymous warehouses, wherein manufactured goods for export as well as imported, agricultural products harvested by enslaved individuals were stored for George’s Dock (Images at top and below).

Address: George’s Dock Ventilation and Central Control Station of the Mersey Road Tunnel, George’s Dock Way, L3 1DD.

Head back in the direction from which you approached, turning left by the traffic lights to rejoin Brunswick Street, following the pavement between the Port of Liverpool and Cunard Buildings in the direction of the Pier Head, part of the former UNESCO-designated World Heritage Site (Liverpool was stripped of its status in July 2021 after a UN committee found developments had caused ‘irreversible loss’ to the value of its historic waterfront), and via Canada Boulevard towards the Mersey Ferry Terminal, 320 metres away. Upon entering the foyer, look up to your right – approximately twenty feet – to see an artwork (image below). Sculptor Stephen Broadbent’s 2009 installation includes three pierced steel plates, representing the continents comprising the Triangular Trade, and a glazed panel etched with slave-trading routes embodying the Atlantic, which connected all three. The words and musical notation of Amazing Grace (1772) flow throughout since there’s a connection between the lyrics, which were penned by John Newton (1725-1807), and the melody, which emerged from ‘the descendants of the slaves [he] transported from Africa to America’.

Address: Pier Head, Georges Parade, Liverpool, L3 1DP.

Exit the Mersey Ferry Terminal building through the door which you entered and turn right onto Georges Parade, continuing in this (south-east) direction until you reach the Museum of Liverpool, whereupon you turn left onto Mann Island so as to pass underneath its huge floor-to-ceiling window before taking a right – bypassing the main entrance – and veering to the left, towards the Great Western Railway warehouse, and specifically an information board in front of the first of two Grade II-listed Graving Docks (two images below). The paved surface is flat, albeit especially slippery when rained upon, and the distance traversed is 320 metres.

Canning dry docks were initially constructed in 1765 for the repair and maintenance of ships; they were subsequently lengthened and deepened in the first part of the nineteenth century, suggesting that the American slaver Nightingale was likely illegally outfitted here during a near-two month stay in the port in 1860. They were home to a cacophony of noise given Mersey shipyards were the ‘place of construction’ (as listed in the Slave Trade Database) for over a quarter of vessels (precisely 2,120) engaged in vile voyages between 1701-1810. These are the oldest, above-ground part of Liverpool’s dock system and indubitably its most direct link with the Transatlantic Slave Trade, with these structures helping to undergird a trade believed to have generated 40 percent of the town’s wealth by 1807.

While this location isn’t directly representative of suffering or death, not least when compared with the slave forts of West Africa or plantation houses in the American South, this northern corner of the trading triangle is inextricably linked with the other two, meaning its association with kidnapping and enslavement renders it a “dark” heritage site, something Philip Stone – founder and Executive Director of the Institute for Dark Tourism Research at the University of Central Lancashire – intimates when listing the International Slavery Museum (ISM) in his 111 Dark Places in England That You Shouldn’t Miss. (This section of the waterfront is due to be redeveloped, with plans featuring a series of bridges opening the dry docks up to help bridge gaps in knowledge through an educational experience shedding light on its “darker” history in a responsible and ethical way, thereby demonstrating that “dark tourism” has evolved beyond mere sensationalism and ‘fascination with assassination’, to quote the subtitle of a seminal article written on the subject in 1996.)

Address: International Slavery Museum (located inside Merseyside Maritime Museum), Royal Albert Dock, Liverpool, L3 4AQ. Open Tues-Sun and bank holidays, 10am-6pm. It is one of seven museums comprising National Museums Liverpool, with the other six being: Museum of Liverpool; World Museum; Maritime Museum; Walker Art Gallery; Sudley House; and Lady Lever Art Gallery.

The ISM will be marking its 15th anniversary in 2022, after opening on 23 August 2007 – Slavery Remembrance Day in the bicentenary year of the Slave Trade Abolition Act. It contains three accessible and engaging themed galleries: Life in West Africa, Enslavement, and the Middle Passage and Legacy. The first and third will open minds, respectively, in terms of the variety and vitality of West African society prior to the landing of Europeans and achievements of Black figures notwithstanding racial discrimination: the product – not premise – of slavery, as author of Capitalism and Slavery Eric Williams elucidates. The second gallery will leave museumgoers open-mouthed, however, since ledgers containing columns of Africans listed as an abstract monetary value alongside tangible tools of torture combine to provide a gut-punch, chillingly illustrating how racial capitalism demanded the systematic and brutal dehumanisation of those forcibly transported. Aside from the ‘Liverpool Street’ signs display (still cornered off due to ongoing research), all other interactive installations are back online (after being offline even when ISM was open outside of pandemic-enforced lockdowns), which younger visitors will discover particularly illuminating, while older ones will regard rehumanisation of the enslaved through a reappraisal of their agency but one of many reasons to visit this priceless yet free museum.

Photo Credits: All images except Gorée Island are by Lee Ruddin.

I’d like to thank the following academics for not only taking the time to acknowledge my emails, but for replying with such lengthy insight and, in some instances, for forwarding on articles: Paul Pickering, Elizabeth Wallace, Itay Lotem, Philip Stone, Velvet Nelson, Charles Forsdick, Stephen Small, Jessica Moody, Helen Baker, Richard Sharpley, and Marcus Wood. I’d also like to thank my first-rate sister and idol, Kirsty, for two of the photographs featured in this three-part article: the stoicism and selflessness displayed in the face of adversity continues to inspire her adoring, younger brother. This article is dedicated to my friend and local historian, David Hearn.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.