by Georges Fery

It was dark, for there was no Sun when the gods met. They said, “who will bring the Sun?” For, after the fall of the Fourth Sun, “all was darkness, there was no Sun” (Leyenda de los Soles, 1558). There have been five suns or ages, each unique and unrepeatable. The first was the Age of the Earth, followed by the Age of Great Winds, the Age of Fire, the Age of Floods, and the present age of Earthquakes. The first four conform with the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. To each age one of the five cardinal directions were assigned locking the Otomi and later Aztec’s spiritual structure of space into that of time (Brundage, 1979:27). The first four suns were imperfect and ended in collapse, the fifth is the present one and there will be no more. In the Nahuatl language, the name of the Fifth Sun, and the beginning of the current era is called 13-Reed, equivalent to the year 1479 in the modern calendar. Taken together the cycles of the suns made up the complete history of time, of gods, of man, and the epic of creation. All of this is finely carved on the twenty-five tons Sun Stone now in Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology and History. The Sun Stone is not a calendar but a calendrical reference to the cyclical concepts of time in relation to cosmic conflicts in Aztec ideology (Kelin, Cecelia F., 1972) .

Let us focus here on the symbols carved at the center of the monolith which depict Tonatiuh’s face, the Fifth Sun deity, whose tongue takes the form of the sacrificial knife, the tecpatl. On each side of the face are two clawed hands holding a human heart, synonymous with both life and the sun god’s rule over it. The four small circles above and below each of the clawed hands are Ollin symbols denoting the movement of the Fifth Sun (Nam Ollin). Each of the four squares that surround the center are glyphs of the previous four suns or eras. On top right is “Four Jaguar” (Nahui Ōcēlotl), when the first era ended. Top left is “Four Wind” (Nahui Ehēcatl), when the hurricane winds destroyed the earth. Bottom left is “Four Rain” (Nahui Quiyahuitl) when earth was destroyed by continuous fires. At bottom right is “Four Water” (Nahui Atl), an era that ended when the world was flooded. Furthermore, the glyph 4-ollin is symbolic of hule, a natural elastic substance from tropical plants that was used to make balls for games. It suggests that, without constant impulse by players, a ball will slow and eventually stop; like the fourth sun did. Of note to those unfamiliar with ancient cultures, there is no barrier between myths and reality, they are one and the same.

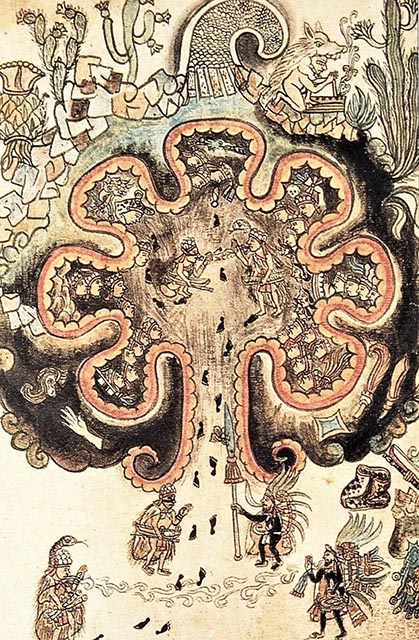

Two cities loom large in Aztec mythology: Teotihuacán and Tula in central Mexico.The first overhelmed the ancient Toltecs upon who they imposed their social and religious culture, while Tula cast its spell over the ogled-eyed Chichimecs. The legends relate that once at sunrise, in the Chihuahua desert of northern Mexico, seven Chichimec groups came out of Aztlan, their legendary seven caves at Chicomoztoc. This mythic world was the birthplace of the Aztecs, also called Mexicas, together with the Tepanecs, Acolhuas and four other nahuatl-speaking groups who migrated toward central Mexico in the eleventh-to-twelfth century. On their way south, while camping on a stream, arguments arose among group leaders as to what was the way to a better life. At the height of the argument, under a blue sky, a bolt of lightning struck a large tree under which they had gathered, splitting it in half. This event was understood as a command from the gods that prompted the dissidents to head out their separate ways.

They all spoke the nahuatl language. Scholars point out that it was the Toltecs who enriched the mythology and added to the Chichimec stock of gods the all important figures of the four Tezcatlipocas. Each of which presided over one of the four cardinal directions and their attendant deities. The gods precondition for their benevolance, however, required sacrifices and the shedding of blood, but why? Self-inflicted or collective spilling of blood was common in Mixtec, Aztec, Maya, and other Mesoamerican religions. Miller and Taube underline that since gods gave their blood to create humans it was understood that human blood was the utmost gift to the gods, thus asserting a mutual dependence. Blood, therefore, spilled through self-inflicted wounds, shed on the sacred stone (techcatl), collectively in war or for religious events, were believed to feed the gods demands to renew the original bond with humans and their divine food. (1997:46).

There are many legends and myths about Huitzilopochtli’s birth among which is the one that tells the story of his mother Coatlicue, (the Earth), who was impregnated by receiving a ball of humming-bird feathers on her chest, which she put in her apron, while attending duties on Mount Coatepec or Serpent Hill, near Tula. Among her children were the four hundred Centzon Huitznahua related to countless stars in Aztec mythology. Their sister Coyolxauhqui (the Moon) furiously demanded that her mother reveal the father’s name. The mother refused so, angered by her perceived deceit and with her brothers, Coyolxauhqui decided to kill her. The mother was frightened but Huitzilopotchli (the Sun in her womb) told her not to fear. When the brothers, the stars, and their sister the Moon launched their attack the Sun burst forth from his mother’s womb fully grown wearing his magic battle gear. He fiercely counter-attacked beheading his brothers and sister, whom he cut into pieces. He then cast the body parts down from Coatepec’s hilltop, drenching the Serpent Hill with blood. Coyolxauhqui is shown, hacked to pieces by her brother, is seen on the carved round massive stone that bears her name found in 1790 at the bottom of the steps of the god’s great temple.

In this mythic worldview the Sun is perpetually battling the Moon and the stars underlining the Aztec’s unquenchable need for human blood to foster the Sun’s sustenance. Huitzilopochtli was said to be in a constant struggle with the darkness and required nourishment in the form of sacrifices to ensure the sun would survive the cycle of fifty-two-years, which was the basis of many Mesoamerican myths.

Urged by Huitzilopotchli, for over two hundred years, the Chichimecs battled their way from Chicomoztoc to the central plateau of Mexico by way of Tula. Famine and wars between 1070 and1077 led to the social breakdown of the Toltec culture and their migrations from Tula to other parts of Mesoamerica, in the twelfth century. Much of Tula’s history was lost when the Aztec Tlatoani Itzcoatl (1427-1440), burned the Toltec codices. Prompted by Huitzilopotchli on their long trek, the Aztecs overcame adversity and the tenacious hostility of many people whose lands they crossed or dwelled for a time and kept heading south over ancient trade routes. In spite of harships and setbacks, time-and-again they were proded by their god to move further south, with the promise of a great future. Their persistence paid off, for they ultimately settled on muddy islets on Lake Texcoco’s shores on the central plateau of Mexico, a place they would call their own.

The Crónica Mexicayotl (1610) tells us that the eagle on a prickly pear cactus (nopal) holding a tuna in its claws is allegorically, the image of the sun feeding from the hearts of sacrificial victims, which proclaimed Aztec power through human sacrifice (Duverger, 2007, 554-555). There are many versions of the eagle holding a bird or a snake. In this last case, Huitzilopotchli told the Mexica searching for a home, to look for an eagle on a prickly pear cactus devouring a snake, a depiction shown on the coat of arms of the Republic of Mexico.

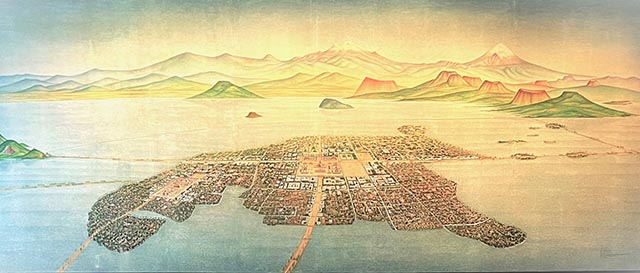

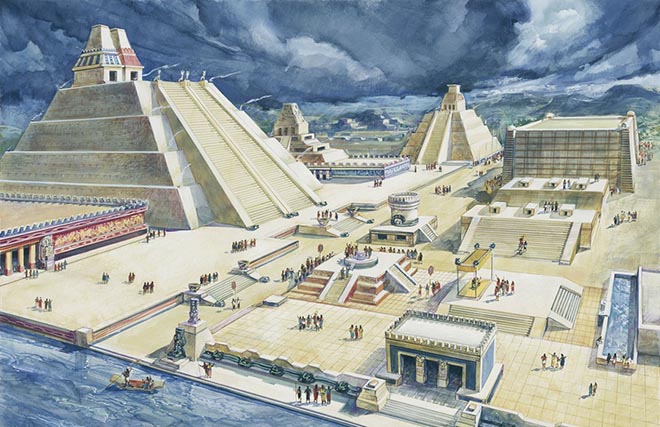

As Huitzilopotchli promised, the grand priest Tenoch drew the footprint of the Aztec capital in 1325. Within a few years and hard work of landfilling the shallows of the muddy islets and lake shores with rocks and earth, they gained firm ground. Despite their neighbor’s repeated attempts at defeating them such as those of Tacuba, Culhuacán and others on the lake shores, in little less than a century the city master plan, drawn by the high priest Tenoch, grew to cover six square miles and would become the most important in Mesoamerica. It housed over 150,000 inhabitants in four large districts (calpullis), which were socio-cultural units that shared the nahuatl language, beliefs, and customs. Five dikes were built to link other towns on the shores of the lake, along with a large aqueduct that channeled fresh water from a source on Chapultepec Hill. According to Franciscan friar Bernadino de Sahagún (1499-1590), seventy-eight large buildings were erected in the city’s ceremonial center. Among them was the Great Temple (Templo Mayor), a depiction of the sacred mountain of Aztec mythology with the twin temples of the gods Huitzilopotchli and Tlaloc at its top.

Of note is that in the cultures of the Americas there were gods for everything; they were everywhere, visible, or invisible. The gods of nature – from mountains to lakes and oceans, the weather, and the animal world – were beyond numbers. Nighttime gods were attached to myriads of stars. In war, victors would adopt the gods of the vanquished, and vice versa, and it was common to temporarily loan or borrow a god from neighbors. Of course, gods never died. The Aztecs adopted many gods from past cultures, particularly those commanding the alternance of day and night, from which arose the legend of the Fifth Sun (Nahm Ollin), incorporating parts of Toltec creation myths while introducing new ideas to support the Fifth Sun allegory.

The legends of the Suns tell us that the Fifth Sun arose over Teotihuacán, the “City of the Gods” thirty miles from Tenochtitlan (Mexico City today). It recounts that Tecuciztecatl, the son of Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue, was called by the assembled gods to rekindling the Sun. The world was then in an unending darkness, so the gods cried, “Who will carry the burden of rekindling the Sun and bring dawn through sacrifice?” For lives were required by ancient gods as payment for having created humans. Tecuciztecatl volunteered to be the first sacrificial victim; the assembled gods then called the humble deity Nanahualitzli as second, and he agreed to their demand. On a large platform facing the monumental Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacán, the gods prepared an enormous sacrificial pyre that burned for over four days while the rituals and penances of the two volunteers took place. At midnight of the fourth day while the pyre burned fiercely, the gods called Tecuciztecatl to jump into the fire to burn and rise as the Sun; Nanahualitzli would then follow and rise as the Moon. Four times Tecuciztecatl ran to the pyre but was held back by the fierceness and heat of the flames. The gods then called Nanahualitzli who without hesitation, calmly walked and jumped into the fire, Slowly as he burned, dawn lightened the sky. Tecuciztecatl, seeing the heroic death of Nanahualitzli, followed into the pyre, was consumed by the fire, and rose as the Moon. Re-energized, Tonatiuh the fiery Sun god, became the warrior sun harboring, from rise to zenith, the souls of those who died in battle and from zenith to sunset, the souls of women who died in their first childbirth.

This creation story reinforced the belief that the Fifth Sun demanded repeated shedding of human blood on the sacrificial stones of Tenochtitlan temples.

The Mexica or Aztec empire was governed by two prominent figures, the Tlatoani and the Cihuacoatl. The Tlatoani was an autocrat whose absolute civil and spiritual powers ruled the male domain and the sky deities among which was Tezcatlipoca. Second to the Tlatoani, the Cihuacoatl, was spiritually associated with the namesake goddess of childbirth, was the “esteemed advisor” to the Tlatoani and ruled Tenochtitlan.

The reference to Cihuacoatl in his title underlines the nature of duality shared between both leaders that pervaded Aztec worldview and spiritual life. It was Tlacaelel who reformed the Aztec religion and put Huitzilopochtli at the same level as Quetzalcoatl, Tlaloc, and Tezcatlipoca, making him a solar god. Huitzilopochtli then replaced Nanahualitzli, from the Nahua legend. In 1428 the Cihuacóatl was Tlacaelel, a well-born noble with a sharp mind. Together with Netzahualcoyotl (the Tlatoani of Texcoco) and Totoquihuatzin (lord of Tlacopan), he was the architect of the Triple Alliance (1428-1521), which begun a round of conquest that, in less than a century, would encompass a vast territory with over four hundred cities and towns. The Triple Alliance greatly expanded Aztec political, economic, and military dominion over central Mexico, south to the isthmus of Tehuantepec and beyond to today’s Guatemala.

Many city-states (atlepetl) within the alliance were fiercely independent, with their own customs and languages. The two-fold Aztec objective was political domination and control of resources for economic growth and expansion of the state. An allied city-state supplied manpower and resources to Tenochtitlan while in return the central government gave local governments military protection and articles or products that would otherwise be unattainable. War also provided slave labor for state building projects and sacrifices for religious ceremonies, for temple priests wanted to be paid with sacrificial lives for their support. The Aztecs efficient military structure and power projection in the region grew rapidly, which allowed for daily supply of goods and services carried to the power center from allied and conquered cities.

Every Aztec male twelve to fifteen years old received basic education and military training in their schools (telpochcalli). The army was a major opportunity for upward social mobility through success on the battlefield, particularly for commoners (macehualtin). For this reason, the expectations of nobles (pipiltin) and commoners alike, revolved around war, which became the driving force of their society and its policies. Shortly after taking office, a Tlatoani had to show his ability as a warrior. His first campaign would make it clear to subject polities that his rule would be as tough on any rebellious conduct as that of his predecessor. Should his first military campaign be a failure, it would be seen as a very bad omen for his rule and could lead to rebellions of city- states (atlepetl).

The troops were made up of common men who were not paid for their service which was regarded as tribute labor to the state. The local civil representative (tlatocayotl) from each district led the troops. Officers were trained in the university (calmecac) and came from the nobility. Their weapons were clubs lined with sharp obsidian stone blades (macahuitl), deadly dart throwers (atlatl), bows, clubs, and knives. Nobles had benefits attached to their social status, among which was their protection on the battlefield by battle hardened Eagle and Jaguar warriors. The political and economic contributions to the state were important, however, they were not always the primary goal for war. Besides its purpose for defense and maintaining socio-political, and economic order, war was foremost the purveyor of victims for sacrifices to the god of war Huitzilopochtli and to the god of rain, Tlaloc and a swarm of other deities.

The Aztecs incorporated parts of other Mesoamerican myths while they introduced new ideas to support the Fifth Sun allegory. To understand from where these demanding gods came, we need to briefly visit the dawn of humanity. The anthropological record tells us that then men were tasked to hunt and protect the group. Women’s roles, beyond that of caring for children and older family members, were to attend to the sick and the maimed. Older men and women were then tasked to search for edible plants and select those that would help in curing illnesses and wounds. Through time, trial and error, mind-bending substances derived from plants were singled out for medicinal purposes. In the Americas, Ayahuasca (Banisteriopsis caapi), Peyote (Lophophora williamsii) and cannabinoids (Cannabis indica), among many, were used to alleviate pain, and later to attain visions that opened the mind to a singular world of uncommon human and animal-like shapes. The reflections from altered consciousness, however, were associated with reality for the figures of those singular beings carried the same familiar traits as those of the living, such as deceit, anger, duplicity, and desire. As Allegro notes “…for such a glimpse of heaven men died…while great religions were born, shone as a beacon to men struggling still in the unequal battle with nature, and then they too died, stifled by their own attempts to perpetuate, and codify the mystic visions” (1970).

Sacrifices to the beings of this “other world” shamans said, were the requisites to make sense of a hidden and unpredictable nature. Foremost, however, human sacrifice was grounded in the belief of a debt that must be paid back to the gods for creating humans and everything on earth necessary for their daily sustenance (Graulich, 2003:17). Each aspect of life, in the Aztecs mind, revolved around this debt that must be paid to gods and deities with gifts from the fruits of the land and sacrifices of wild and later, domesticated animals. This commitment to paying the debt of life had many ritual and theological dimensions. Eventually, the welfare of the living required to feed these insatiable man-made gods with human lives. In smaller towns with no monumental architecture, gods received sacrifices through their earthly depictions made of wood, paper, or stone called ixiptla. Upon sacrifice, a victim’s blood was collected in a ceramic or stone bowl in which soft paper was soaked and used to swipe the eyes, mouth, and face of a select deity’s likeness (ixiptla), while at the same time, pleading for its help or mercy.

To answer their gods’ demands, the Aztecs slayed people on a massive scale. At least seven types of human sacrifices took place, among which were heart extraction, shooting with arrows, gladiatorial combat, beheading and offering children to the gods. We will limit our inquiry to three of them. Ancient texts relate the birth of human sacrifice at Teotihuacán, a ritual borrowed by the Toltecs at Tula, and named the god Tezcatlipoca as its generator. In Tula’s last days (1150), Tezcatlipoca taught people to sacrifice those captured in war. The historical record show that the Aztecs acquired the cult of human sacrifice from the Toltecs, which would explain why it was adopted as a dogma, for the gods had originated it and the venerated Toltecs passed it on. As inheritors of such long held beliefs the Aztecs could not conceive of gods and their welfare without human sacrifice for only then could men be beholden to the supernatural order (Brundage, 1977:32). Most of the ceremonies involving such sacrifices were associated with the 365-day solar calendar and the 260-day sacred calendar. The solar celebrations were especially important, for they recreated various ritual aspects of the Mesoamerican cosmogony such as the rise of the Sun and its rekindling via human sacrifice. These agrarian celebrations took place monthly and were related to the eighteen months calendars such as, planting, harvesting, equinoxes, and solstices among others. Natural events were understood to be governed by an unpredictable nature in the hands of gods, among which were Chicomecoatl, goddess of agriculture, and Xilomen deity of the main food staple, maize.

This is Part One of a Two-Part Article.

Part Two will be published at a later date.

References – Further Reading:

Arqueología Mexicana:

Los Tlatoanis Mexicas – EE.40

Aztecas, Cultura y Vida Cotidiana – EE.75

Los Ejes de Vida y Muerte en el Templo Mayor y en el

Los Dioses de Mesoamérica – Vol.IV-20

Investigaciones Recientes en el Templo Mayor – Vol.VI-31

Plantas Medicinales Prehispanicas – Vol.VII-39

La Muerte en el Mexico Prehispanico – Vol.VII-40

El Sacrificio Humano – Vol.XI-63

La Guerra en Mesoamérica – Vol.XIV-84

Coyolxauhqui, Diosa de la Luna – Vol.XVII-102

Los Tzompantlis en Mesoamérica – Vol.XXV-148

Alfonso Caso, 1953 – El Pueblo del Sol

Padre Andrés de Olmos, 1530 – Historia de los Mexicanos por sus pinturas

Nigel Davies, 1987 – The Aztec Empire

Ross Hassig, 1988 – Aztec Warfare, Imperial Expansion and Political Control

Rebekah C. Bellum, 2015 – Narrative of Violence and Tales of Power

Broda, D. Carrasco, E. Matos Moctezuma, 1987 – The Great Temple of Tenochtitlan

Christian Duverger, 2007 – El Primer Mestizaje

John M. Allegro, 1970 – The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross

Anthony Aveni et al., 2023 – Aztec Myths and Legends

Nigel Davies, 1977 – The Toltecs, Until the Fall of Tula

Fray Diego Duran, 1569-1582 – Historia de las Indias de Nueva-Espana e Islas de Tierra Firme.

Berrin, E. Pasztory, 1993 – Teotihuacan

About the author:

Creative non-fiction writer, researcher and photographer, the author’s articles are about the history of the Americas before European arrival, their culture and beliefs. His articles are published online at travelthruhistory.com, ancient-origins.net and popular-archaeology.com, in the quarterly magazine Ancient American (ancientamerican.com), as well as in the U.K. at mexicolore.co.uk. The author is a fellow of the Institute of Maya Studies instituteofmayastudies.org Miami, FL and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org; as well as member in good standing of the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org, the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org, the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. americanindian.si.edu, and the NFAA – Non-Fiction Authors Association nonfictionauthrosassociation.com.

Contact: Georges Fery – 5200 Keller Springs Road, Apt. 1511, Dallas, Texas 75248, (786) 501 9692 –gfery.43@gmail.com and www.georgefery.com

Photo Credits:

Ph.01 – Nam Ollin, the Sun Stone @georgefery.com

Ph.02 – The Sun Stone’s Core @georgefery.com

Ph.03 – Chicomoztoc Seven Caves @arqueologiamexicana.mx

Ph.04 – Coyolxauhqui’s Stone @georgefery.com

Ph.05 – Tenochtitlan, 15th Century @georgefery.com

Ph.06 – Teotihuacán, Pyramid of the Sun @ Mario Roberto Duran in wikipedia.org CC BY-SA 4.0

Ph.07 – 1487 Tenochtitlan Great Temple @discoverymagazine.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.