By Georges Fery

The sight of a man dancing on a tiny round platform atop of a hundred foot-high wooden pole while playing a flute and a small drum is baffling, and strikes fear in the heart of his loved ones and onlookers alike. It is even more spectacular when his four companions, seated on a makeshift structure tied up below him at the top of the pole, drop head down with nothing but a rope attached to their waist. They are the Papantla pole dancers, also known as flyers, natives of the indigenous community of Papantla located in the state of Veracruz, Mexico. Papantla was founded by groups of Totonacs who were compelled to migrate from the central plateau of Mexico, after the fall of El Tajin (600-1230). The Mexican artist Diego Rivera (1886-1957) recorded one such ritual set at El Tajin in the twelfth century on murals of the former presidential palace in Mexico City. In 1733-1735, the Franciscan fray Francisco Antonio de la Rosa Figueroa led a campaign to eradicate the dancer’s ritual in Xochimilco societies.

Of interest is that pole dancing was not practiced in Classic Maya (250-900), whose mythology of the creation of the world is associated with the bird deity Itzamna dwelling in the World Tree, the center of the world. Ancient Mesoamerican rituals correlate with the centuries old 365-day agricultural cycle, or year count (xiuhpõhualli), and the 260-day ritual cycle (tõnalpõhualli), or day count. These calendars were used by the Nahua, Totonac and Huastec people, who eventually made it to Papantla.

The ritual is found in a number of myths, such as with the Totonacs, which relates that over five hundred years ago, there was a persistent drought that brought hunger and death. The gods were believed to withhold the rains when people neglected them. The ceremony was then created to appease the gods and appeal to them to bring back the rains. The ritual, also called “Dance of the Eagles” (Danza de las águilas) was associated with the sharp cries of birds of prey, which were imitated by the fliers’ lead actor, the k’ohal or corporal, who blew high pitched sounds from a small bird bone whistle while dancing on top of a tall wood pole. It was later commonly called “Dance of the Flyers” (Danza de los voladores). (The name “flyer” is a translation of the Spanish voladores, associated with birds, while “dancers” is more often found in texts).

The Huastecs held the ceremony once a year to celebrate all of their divinities in order to reap the full extent of their favors in a one-time event. The hallmark of the ritual was the boldness of the dancers, associated with the fear of the fall of a team member. The risk was highest for the leader or one of the teams who, alternately, would stand and dance unsecured on the round foot-square capstan, called manzana (apple), atop a hundred foot high pole. Ancient rituals were complex and often blended the secular and spiritual conceptions of a community’s religious universe that, to some extent, still survive in traditional societies today. Rituals, by definition adhere to strict rules that are deeply rooted in ancient symbolism. The sons of Totonac and Huastec dancers followed their ancestors’ tradition when they reached twelve years of age or manhood status. At that time, they started a training regime, both secular and spiritual, that would last a decade or more. Today, with some exceptions, the complex rituals are mostly forgotten. Our knowledge of them is largely owed to the French ethnologist Guy Stresser-Pèan who, in 1937 and 1938, lived among Huastecs pole dancers, and recorded their prayers, chants and traditions.

Pole dancing rituals are predicated on sun and moon cycles, and are deeply rooted in ancient farming communities’ beliefs and traditions. Most ancient rituals are grounded in complementary opposites, such as night-day, up-down, male-female or life-death among others, fused with nature and roots and complexity of ancient agrarian beliefs. According to tradition a team of dancers was made up of five men who, after initiation, were regarded as agents of the four cardinal directions and the vertical zenith-nadir. The historical record from the 16th and 17th centuries depicts pole dancing associated with human sacrifice. Drawings of the time show arrows shot at a naked man tied up spread-eagled on a wooden frame, with pole dancers in the background. This custom, associated with the Nahuatl society of central Mexico, is in contradiction with traditional pole dancing rules, and may not have taken place at the same time, despite ancient depictions. In the past and with indigenous groups today, teams numbered six – and at times eight – dancers. Traditionally, however, there were three to four teams of four flyers in a community each led by a k’ohal, as team leader also referred as corporal, who danced standing unsecured on top of a pole. The pole was then perceived to be at the intersection of the five cardinal directions, the axis mundi. The k’ohal would call and plead to the deities for the team’s safety, turning alternately to the east, north, west, and south, symbolically correlated with earth, air, fire, and water, and those of the zenith-sun and the nadir-moon. He also pleaded with the deities to accept his team’s offerings and bless the dangerous ritual about to take place. It was believed then, that the k’ohal pleas were like those of an eagle that, from the top of a tree, loudly shrieked asking the sun’s permission to catch a prey.

Who started the first dance of the day varies among ethnic groups. For the Huastecs and the Totonacs it was the musician who would climb first to the top of the pole for the first dance of the day. The k’ohal (corporal) of each team would then head the following dances. The rituals aimed at bringing the conjunction of warm forces associated with light in the upper world and the cold forces of darkness in the underworld through the pole.

Referred to as complementary opposites, they are foremost in understanding ancient agrarian spiritual beliefs and rituals, for they were perceived as indispensable to life’s renewal in the middle world of people and nature. Each of the four dancers personified one of the four cardinal directions and their respective dynamism. Tied at the waist by a rope, the dancers fell from the top of the pole revolving counterclockwise on their way down. Each completed a circular cosmogram of thirteen revolutions (13×4), associated with the 52-year cycle or “century” of ancient times. Rituals before, through and after the event were attended by a shaman, a ritual orator and a musician with a small flute and a little drum tied to his finger, who danced at the foot of the pole, playing dedicated tunes for each phase of the ceremony.

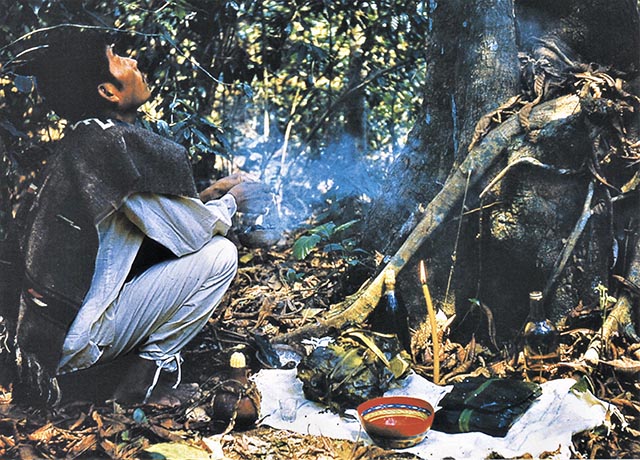

The day before the ritual, the shaman, the ritual orator, the musician and a large retinue of men, left the village to search and cut down a young but strong tree such as a cedar or a fir in the forest mountains nearby. The tree had to be strong and its trunk as straight as possible up to a hundred feet above the ground. When the tree was found, before cutting it down, pleas by the ritual orator were addressed to the gods of the forest, the deities of the four cardinal directions and those at the center of the world, asking for permission to cut it. Five times the ritual orator would beg the deities and tell them why the tree was needed and how it would be used. At the same time, the musician (tùlim), with his short flute and little drum, played the “tune of the middle earth” (Son del medio de la tierra), repeated with pleas to the four cardinal directions. When all was said, the shaman filled his mouth with a coarse brandy that he then blew on the tree’s lower trunk and roots to close the pleas. The tree was then cut with an axe and, ideally, subject to particulars of the terrain, would fall from west to east its top pointing to sunrise.

At that moment, the “tune of forgiveness” (Son del perdón) was played by the musician. The trunk, stripped of branches, was then carried to the village by tens of men headed by the musician playing the repeated five notes of the “travel tune” (Son del viaje), which could not be interrupted for any reason.

Once the tree and its retinue arrived on the village plaza, the first task was to dig a hole to receive it or figuratively, plant it. The trunk was then cleaned of bark and the tree became a pole. Rituals again preceded its placement which ideally should be in the center of the village plaza. There, a circle was drawn on the ground on which the shaman sprinkled a strong liquor such as aguardiente on each of the cardinal directions and at its center for the deities of the earth. While digging the hole, which had a depth of five feet or more, the musician played the four “tunes of the east, west, north and south” (Sones del oriente, poniente, norte y sur) and the “earth’s center tune” (Son del medio de la tierra), while the shaman appealed to the deities and asked the land for mercy for having to hurt it. A makeshift altar was built near the foot of the pole covered with a white tablecloth with five bottles of aguardiente corresponding to a flyers team of four and the k’ohal, a censer for burning copal powder, small cakes and candied fruits. To an altar’s leg was tied a young live turkey or chicken.

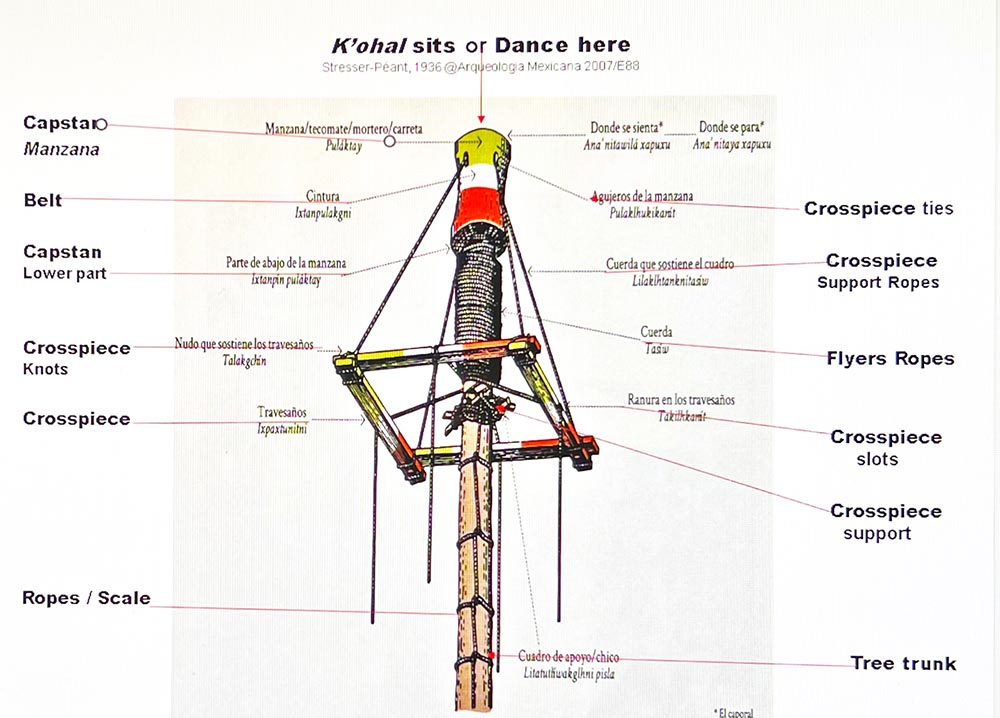

Before burying the base of the pole, a revolving capstan was carefully crafted from hard wood, such as cedar. Deep grooves were carved at right angle on its top to receive the four thick ropes. A hole was then drilled at the bottom of the capstan to precisely fit the shaped top of the pole, which was then filled with grease to smooth its rotation. Then the four main ropes, to be used by the dancers, were loosely attached to the capstan.

Around the pole’s length another rope was wrapped, spaced a foot or so between links, to be used as a step ladder for the dancers and team members. The pole, together with the capstan attached to it, was then lifted up with ropes, chokes and wood levers, together with ample manpower. Before sliding the base of the pole into the hole, however, flowers, copal incense and a live young turkey or chicken which would be crushed by the pole, was thrown in as a sacrifice to please the deities of the earth. All the while in a slow singsong voice the shaman pleaded to the earth goddess to protect the flyers against witchcraft. The sacrifice was the payment to the deities for receiving the pole or else, punishment to the dancers may occur should the sacrifice not be accepted. At that time the “tune of forgiveness” (Son del perdón) was played. Once the pole was up, a team member climbed up to its top and from there, made sure that it was as straight as possible. The pole was then securely set by filling the hole around its base with as many long wood stakes as necessary. Then the musician played the “tune of chain” (Son de cadena), when the flyers, the shaman, ritual orator and support members danced around the pole tied up to each other.

Below the revolving capstan, a quadrangular crosspiece was built made up of four planks from a strong wood, each about three feet or so in length and a foot wide, that was tied up to the pole. This is where the four dancers would sit before launching themselves to the ground. The main ropes were then wrapped around the pole by two old team members who went up the pole using the rope ladder. There, seated on the crosspiece, they moved around the pole with their naked feet, while carefully wrapping the ropes tightly and evenly counterclockwise. At that time the musician on the ground played the “roll up” tune (Son del enrollado). The pole was then spiritually recognized as the world tree connecting the sky, earth, the underworld and their respective deities, together with those of the vertical zenith-nadir fifth direction. Then the team and support members danced around the pole purified with local liquor scattered by the shaman while the “tune of the circle” (Son del circulo) was played.

Nine days before the event, the musician, the ritual orator, the master of ceremony and the flyers, met each evening at the k’ohal’s house to carefully review each phase of the ritual and everyone’s role in it. It is on this first night that sexual abstinence started. During lengthy ritual practice and invocations, team members paused between conciliatory rituals with the gods and ate meals brought from home that was not spiced nor seasoned or with salt or sugar. Rituals and practices were wrapped-up at sunrise when the party danced in circle with the musician playing the “farewell tune” (Son de la despedida), while alternately facing the four cardinal directions.

This is Part One of a Two-Part article.

Photo Credits:

Ph.01 – Pole Dancers at El Tajin @georgefery.com

Ph.02 – Danza de los Voladores @MarcoAntonioPacheco, arqueomex.com

Ph.03 – Of Trees and Pleas @Stresser-Pean, 1936 in arqueomex.com

Ph.04 – Top of Pole @Stresser-Pean, 1936 in arqueomex.com

Ph.05 – Climbing the Pole @trevacouturier.com