by Karoline Cullen

I hear a bell. Its persistent peal floats over the trees and ricochets off the stones. “Does that ringing mean something?” I ask. My friend starts walking and says over her shoulder “It’s time to go. We don’t want to get locked in!”

“Definitely not.” I think to myself. Visiting the City of the Dead, as Paris’ largest cemetery Père Lachaise is known, on a sun dappled afternoon is one thing. Being trapped behind the enormous entrance gates for the night is quite another.

“Definitely not.” I think to myself. Visiting the City of the Dead, as Paris’ largest cemetery Père Lachaise is known, on a sun dappled afternoon is one thing. Being trapped behind the enormous entrance gates for the night is quite another.

When the cemetery was established in 1804 by Napoleon I, it was well outside the city walls. Today the 109-acre site is a five-minute walk from my friend’s apartment in the 20th Arrondisement and a favorite destination for a peaceful, contemplative saunter. As 19th century novelist Honoré Balzac said “I rarely go out, but when I do wander, I go to cheer myself up in Père Lachaise.” He is also buried here.

Some clever 19th century marketing of the perpetual concessions for plots was necessary to attract occupants. As the land was once owned by Father Francois d’Aix de la Chaise, the Jesuit sounding “Père Lachaise” was chosen as the cemetery’s name. Remains of some famous dead were relocated for some caché. Twelfth century ill-fated lovers Abélard and Héloise are in a spectacular neo-Gothic tomb in the oldest section. In 1817, the bones of dramatist Molière and writer La Fontaine were moved here as was Louise de Lorraine, widow of King Henri III. Famous or rich or royal or not, or if you died in Paris, a Père Lachaise plot could be yours.

Some clever 19th century marketing of the perpetual concessions for plots was necessary to attract occupants. As the land was once owned by Father Francois d’Aix de la Chaise, the Jesuit sounding “Père Lachaise” was chosen as the cemetery’s name. Remains of some famous dead were relocated for some caché. Twelfth century ill-fated lovers Abélard and Héloise are in a spectacular neo-Gothic tomb in the oldest section. In 1817, the bones of dramatist Molière and writer La Fontaine were moved here as was Louise de Lorraine, widow of King Henri III. Famous or rich or royal or not, or if you died in Paris, a Père Lachaise plot could be yours.

Thousands of trees create a shady canopy in summer. Tree lined cobblestone lanes meander amongst thousands of tombs. Some are simple, many grandiose. Headstones tilt, crypt roofs collapse and gates rust. A jumble of worn, leaning memorials contrasts with the gleaming glass and shiny marble of the new. Stained glass chapel windows illuminated by the afternoon sun are counterpoints to the stone walls and dead vines entwined on a chapel door. Blooming shrubs and colorful flowers add hits of colour.

I am moved by the dramatic monuments to the WWII deportees and resistants. The statuary is stark, haunting, and brutal. The Mur des Fédérés (Wall of the Federalists), against which 147 Communard insurgents were shot in 1871, still bears bullet scars. They are buried in a mass grave at its base. Amid the memorials marking tragedy and death, I unexpectedly find it peaceful here.

Jim Morrison’s Grave

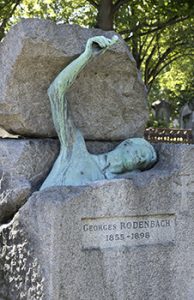

There are, however, many “popular” residents to pay homage to and millions do each year. Edith Piaf, songbird of the 20th, has plenty of long-stemmed red roses left for her. She is just down the hill from Oscar Wilde, who claimed to “be dying beyond his means” in Paris. The plexiglass protecting his tomb is covered with lipstick kisses. A group of youngsters surreptitiously parties next to the cordoned off grave of The Doors singer Jim Morrison. Flowers, flags, and musical instruments festoon the base of Polish composer Chopin. A statue of Euterpe the weeping muse of music, supervises the scene. The statuary ranges from the expected weeping angels and chubby cherubs to the bizarre like the winged skulls on magician E. Robertson’s tomb. I cannot decide whether the bronze figure on the tomb of 19th century Belgian writer and poet George Rodenbach is climbing into or struggling out of the grave.

There are, however, many “popular” residents to pay homage to and millions do each year. Edith Piaf, songbird of the 20th, has plenty of long-stemmed red roses left for her. She is just down the hill from Oscar Wilde, who claimed to “be dying beyond his means” in Paris. The plexiglass protecting his tomb is covered with lipstick kisses. A group of youngsters surreptitiously parties next to the cordoned off grave of The Doors singer Jim Morrison. Flowers, flags, and musical instruments festoon the base of Polish composer Chopin. A statue of Euterpe the weeping muse of music, supervises the scene. The statuary ranges from the expected weeping angels and chubby cherubs to the bizarre like the winged skulls on magician E. Robertson’s tomb. I cannot decide whether the bronze figure on the tomb of 19th century Belgian writer and poet George Rodenbach is climbing into or struggling out of the grave.

Some are more famous in death than they ever were in life. Victor Noir, a young 19th century journalist, is memorialized by a life size bronze effigy depicting how he lay after being shot by a cousin of Napoleon III. Women wishing for fertility have rubbed a certain well-endowed body part and made it gleam against the verdigris of the rest of the statue.

Some are more famous in death than they ever were in life. Victor Noir, a young 19th century journalist, is memorialized by a life size bronze effigy depicting how he lay after being shot by a cousin of Napoleon III. Women wishing for fertility have rubbed a certain well-endowed body part and made it gleam against the verdigris of the rest of the statue.

A plot surrounded by potato plants is my favorite discovery at Père Lachaise. A ring of potatoes left on the rim of the tombstone are a fitting tribute to agronomist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier. In the late 1700s, he promoted the potato as a food source. Up until that time, the potato was considered only fit for animal feed. Parmentier persisted with his campaign and the subsequent planting of potatoes helped stave off starvation for many Europeans.

Our amble amongst the long dead comes to a halt with the persistent ringing of the closing bell. A black bird settles on the edge of a crypt but flutters aloft as we pass. The stony eyed bell ringer gives not a glance as we wave adieu and step through the gates into the late afternoon sun.

If You Go:

Père Lachaise Cemetery

16 Rue du Repos, 75020 Paris, France

Metro: Philippe Auguste, Père Lachaise or Gambetta

Maps of notable graves are available at the office.

Paris Père Lachaise Cemetery Private Walking Tour

About the author:

Karoline Cullen always travels with camera and pen at hand. Her works have been published in numerous newspapers, magazines, and on-line and she is a member in good standing of the British Columbia Association of Travel Writers. www.cullenphotos.ca

Jim Morrison’s grave photo by Effervescing Elephant / CC BY-SA

All other photos by Karoline Cullen, Cullen Photos

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.