by Leslie Hebert

I am on the Bund in the heart of Shanghai. Behind me are European-style neo-classical buildings erected at the beginning of the twentieth century to house international banks and trading companies. In front of me glistening office towers keep watch over barges that plough through the brown waters of the Huangpu River. On the far bank is a forest of giant skyscrapers. The twisted, corkscrew shape of the world’s second tallest tower, the 632 meter high Shanghai Tower, dwarfs the “bottle-opener” top of the neighboring Shanghai World Financial Center, the world’s sixth tallest building at a mere 492 meters in height.

I am on the Bund in the heart of Shanghai. Behind me are European-style neo-classical buildings erected at the beginning of the twentieth century to house international banks and trading companies. In front of me glistening office towers keep watch over barges that plough through the brown waters of the Huangpu River. On the far bank is a forest of giant skyscrapers. The twisted, corkscrew shape of the world’s second tallest tower, the 632 meter high Shanghai Tower, dwarfs the “bottle-opener” top of the neighboring Shanghai World Financial Center, the world’s sixth tallest building at a mere 492 meters in height.

Shanghai, a mega city of 24 million, has thrived on trade for over 2,000 years, since the origins of the ancient Silk Road. Earlier that day in the Shanghai Museum I had seen a fascinating hoard of Silk Road coins donated by a wealthy private collector. I stared at coins of shining gold and darkened silver. I gazed at coins inscribed with Chinese, Indian and Arabic script. I wondered at the stern faces of unknown rulers from long forgotten empires in central Asia and the Middle East, and noticed how bareheaded, beardless faces with long, straight noses contrasted with hook-nosed faces bearing long, intricately curled beards.

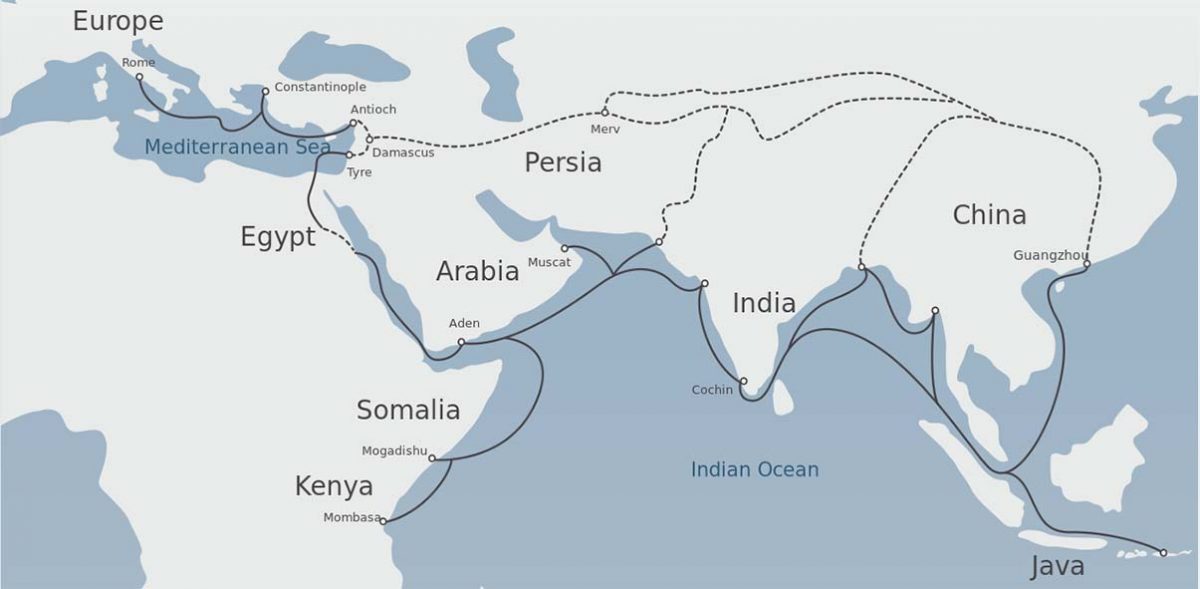

If one of those faces could talk it might tell of its travels along a vast trade route which united Asia, the Indian subcontinent, Russia and Europe to the west with Korea, Japan and Indonesia to the east. It might spin a yarn about how traveling overland from Europe and by ship across the Mediterranean to legendary ports such as Constantinople or Antioch. There, the coin bearing its image may have purchased valuable products from China or exotic spices from Indonesia which had traversed the high mountain kingdoms of Tibet and Nepal to the great Persian Empire and beyond.

The Silk Road enabled China to imported western products such as honey, grapes, wool, glassware and powerful Bactrian war horses bred by descendants of Alexander the Great’s army. In return, the Middle Kingdom exported tea, porcelain, spices, ivory, rice, paper, gunpowder and, of course, the shining fabric for which the trade route was named.

China maintained its silk monopoly for hundreds of years by jealously guarding the secrets of silk production. Revealing the source of silk was a crime punishable by death. Of course, it is now no longer a secret that silk is produced by silkworms or, more accurately, the caterpillar of the silk moth, Bombyx mori.

From Shanghai our tour took us to Souzhou, a city at the heart of the ancient Silk Road. At a local factory, I learned about the life cycle of the silk moth. When the caterpillars hatch they are as thin as a piece of thread and about a quarter of a centimeter in length, but grow rapidly, multiplying their weight 10,000 times in their short lives . Within a month, by the time they are ready to spin their cocoons, they are obese, greyish-white monsters which I estimated to be about six centimeters in length and almost as big around.

In the factory, amid the deafening metallic clatter of rusty machinery, I watched a worker with a tired, drawn face carefully unwind silk from egg-shaped cocoons which shimmered with a pearly luminescence. Each cocoon can yield up to 1800 meters of continuous fiber so thin that it is virtually invisible. The cocoons, boiled to kill the pupae inside, lay soaking in a trough of water, arranged in groups of eight because it takes the fine fibers from eight cocoons to produce one single silk thread.

In the factory, amid the deafening metallic clatter of rusty machinery, I watched a worker with a tired, drawn face carefully unwind silk from egg-shaped cocoons which shimmered with a pearly luminescence. Each cocoon can yield up to 1800 meters of continuous fiber so thin that it is virtually invisible. The cocoons, boiled to kill the pupae inside, lay soaking in a trough of water, arranged in groups of eight because it takes the fine fibers from eight cocoons to produce one single silk thread.

To feed the spinning machine, the worker’s deft fingers moved from one group of cocoons to another, drawing thread from cottony soft bundles as needed and discarding pupae corpses into a plastic bucket at her feet. The machine drew up the white thread, winding it onto spools which continued along the production line to be dyed elsewhere and then woven into fabric, perhaps for clothing, bedding or parachutes.

Silk thread is also used for Suzhou’s famous embroidery, the ancient art of “painting” with silk thread which has been passed down from master to apprentice for over 2,000 years. After leaving the din of the factory, it was a relief to enter the quiet of a brightly lit atelier where I watched master embroiderers at work. I watched in amazement as a skilled artisan worked freehand to create a shining silver koi which looked like a living, breathing fish leaping joyously into the air. This work-in-progress, our tour guide told us, would probably take three years to complete, and when finished would have been sewn over three times.

I was not surprised to learn that a master of this painstaking craft serves a twenty year apprenticeship, and also that it is incredibly hard on the eyes. Because the ladies need to work in bright, natural daylight, they only work five hours a day. In addition, they can only work for as long as their eyesight holds out. In the days before eyeglasses, I realized, their careers must have been short indeed.

From the workshop, I threaded my way through the showroom to admire incredibly detailed creations which glowed with magical, living beauty. On the wall was a Mona Lisa with flesh tones so subtle that I could not tell it was stitched until I was a foot away. Elsewhere, forest and garden scenes portrayed leaves in multiple shades of green and brilliantly colored flowers, all intricately marbled with complex networks of veins. Silver white cranes posed in a glowing green bamboo forest spreading feathers on which virtually every barb of every feather seemed visible. No wonder the prices of these masterpieces start at $US80,000.

In the center of the showroom, crimson and white koi swam across transparent fabric stretched onto a wooden frame. When I walked around the frame I realized there were no knots or loose threads on the back. In fact, there was no right or wrong side because back and front were virtually identical. Elsewhere in the showroom I saw an even more impressive example of double-sided embroidery, a work with different images on front and back. On one side a lion roared ferociously, its glowing golden face covered with realistic-looking, individually sewn hairs. On other side an emerald-eyed tiger returned my gaze. How on earth, I wondered, was this even possible?

Blessed with abundant water, Suzhou is called the Venice of China because of its many canals. The world’s oldest and longest canal is the remarkable 1780 km Grand Canal which flows northward through Suzhou to Beijing, enabling the great merchant families of Suzhou to become wealthy by shipping silk to Beijing. Much of the private wealth of Suzhou was used to create a dizzying number of beautiful classical Chinese gardens, nine of which are UNESCO World Heritage listed sites.

Blessed with abundant water, Suzhou is called the Venice of China because of its many canals. The world’s oldest and longest canal is the remarkable 1780 km Grand Canal which flows northward through Suzhou to Beijing, enabling the great merchant families of Suzhou to become wealthy by shipping silk to Beijing. Much of the private wealth of Suzhou was used to create a dizzying number of beautiful classical Chinese gardens, nine of which are UNESCO World Heritage listed sites.

One of these gardens, the aptly named Lingering Garden, was the next stop on our itinerary. As soon as I entered the garden I was transported away from the hubbub of city life to an oasis of peace. Vases, lying cornucopia-like on their sides, poured cascades of gold and pink chrysanthemum blossoms onto the calm surface of a small lake.

As I wandered from courtyard to courtyard, I become lost in a maze of water and stone. Sparing no expense, the merchant who owned this garden had created a mythical landscape of pavilions, lakes and mountains. Fantastically shaped and perforated limestone rocks dredged from the bed of a faraway lake had been stood on end like twisted megaliths to create miniature artificial mountains. Moss and trees grew on their slopes, and water-lily dotted moats flowed at their feet.

As I wandered from courtyard to courtyard, I become lost in a maze of water and stone. Sparing no expense, the merchant who owned this garden had created a mythical landscape of pavilions, lakes and mountains. Fantastically shaped and perforated limestone rocks dredged from the bed of a faraway lake had been stood on end like twisted megaliths to create miniature artificial mountains. Moss and trees grew on their slopes, and water-lily dotted moats flowed at their feet.

The merchant who created the Lingering Garden was able to run a profitable business thanks to a trade route which had linked east and west since ancient times. It is believed that trade between the Chinese and the ancient Greeks, who called China Seres meaning Land of Silk, began in 200 BC or earlier. It is therefore not surprising that this great trade route carried not only commercial goods but also culture and ideas, and helped to spread religions such as Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam throughout the known world.

I was unexpectedly reminded of this cultural legacy on my last day in China when my husband and I wandered out of our Beijing hotel looking for dinner. We chose an obviously popular restaurant that was filled with smiling customers. We found a table and pored over the pictorial menu lying there, disappointed that there was no sweet and sour pork, or any other pork dishes for that matter. Then I noticed the waiter’s white crocheted cap and realized that he was Muslim and this was a halal restaurant. So, instead of eating pork that evening, we enjoyed the incredible gastronomic experience of fragrant stir-fried lamb with cumin, a delicious and enduring testimony to cultural transmission along the great trading network known as the Silk Road.

If You Go:

If You Go:

Private Day Tour: Suzhou Gardens and Silk Museum from Shanghai Including Lunch

Documentation

You will need to obtain a Visa to enter China before your visit.

Getting There

Shanghai’s main international airport is Hudong. Guided day trips to Suzhou are available from Shanghai. You can also take a domestic flight to Suzhou from Shanghai’s Hongqiao airport. Other recommended activities in Suzhou, in addition to garden tours, include water tours of the city’s historical waterside districts, especially a boat ride along the Grand Canal.

Money

China is a primarily cash economy, so you should obtain enough Chinese Yuan (also known as RMB) before your trip.

Tipping is not customary nor expected.

Sanitation

Tap water is not safe, so you should always drink and clean your teeth with the bottled water provided by your hotel.

Toilets are “squat” style. If this is a problem, you might have to search for a handicapped toilet. These are generally, but not always, indicated with the international handicapped symbol, (One I used was labeled with a handwritten sign that said “for maimed persons only”!).

Bring your own toilet paper and hand sanitizer.

About the author:

Lesley Hebert is a graduate of Simon Fraser University. Now retired from teaching English as a second language in the classroom, she teaches ESL to international students via Skype. She also writes on-line articles which reflect a lively, inquiring mind and a love of travel, language, history and culture. Read more of Lesley’s articles at www.infobarrel.com/Users/HLesley.

Silk Road map graphic by Belsky licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Photographs by Lesley Hebert

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.