by Millie Stavidou

Evros tends to be somewhat off the beaten track for the average visitor to Greece. It is in the northeast of the country, and borders with Turkey and Bulgaria. The people living here count themselves as the descendants of the ancient Thracian people and have a long and proud history.

As with many places, some customs have been lost or changed over time, especially with the relentless march of the modern world and its media. But Evros during the festive season is still a magical place.

In years gone by, a special Christmas meal would have been held in a family group. Known as Ta Ennia Fayia, or the Nine Dishes, this was once a chance for the whole family to get together and celebrate with a full table. These days, although some families in villages scattered through the region do still keep to this, in the town you are more likely to attend such an event hosted at a community centre of some kind. I was invited to Ta Ennia Fayia at the Kappadokiki Estia in Alexandroupolis, a cultural centre.

Evergreen boughs and wreaths decorated the walls, and the long table was covered with a festive cloth. As people came in, many of them brought prepared food from home to place on the table and share with everyone, and there was a hidden meaning to these dishes. Tradition dictates that a particular list of nine ingredients must be included somehow:

one – pie for the wheat, to make it shine

two – honey, so they may carry many things like the bees

three – wine to let them multiply like bunches of grapes

four – saragli, [a syrupy sweet], to make them sweet-natured

five – watermelon to sweeten the year’s produce with many seeds

six – melon for their tongues so they may speak sweet words

seven – apple for the women to make their cheeks red with health

eight – garlic to offer protection from insect bites and the evil eye

nine – onion to give new mothers plenty of milk

These are remembered in the form of a little poem that is chanted at the beginning of the dinner, and there was a lot of good-natured teasing and joking about the forms each ingredient would take and the creativity of the cooks.

Before the meal can start, the Christopsomo, or ‘Christ-bread’ must be broken and offered round. There is a small ceremony, where the eldest member of the gathering places a towel on the head, with the bread on it, and a young child breaks it in half. It is put straight into a basket and offered round. This is the signal that two things can begin: the meal and the dancing. Greek folk dancing can be very energetic, and I was glad that I was prepared. As a visitor, I did not know all the steps, but the local people were happy to see me join in and very welcoming. Nobody minded the odd mis-step.

Before the meal can start, the Christopsomo, or ‘Christ-bread’ must be broken and offered round. There is a small ceremony, where the eldest member of the gathering places a towel on the head, with the bread on it, and a young child breaks it in half. It is put straight into a basket and offered round. This is the signal that two things can begin: the meal and the dancing. Greek folk dancing can be very energetic, and I was glad that I was prepared. As a visitor, I did not know all the steps, but the local people were happy to see me join in and very welcoming. Nobody minded the odd mis-step.

The Nine Dishes is of course not the only feature of the season. There is a local myth about kalikantzari or goblins that live in the centre of the world, sawing away at the roots of the Tree of the World that supports us all. At Christmas, they are able to visit the world above and they come up to harangue us and cause mischief wherever they go. A broken glass, spilled oil, a burnt loaf: all can be blamed on the kalikantzari. Children often perform little plays telling the tale of the kalikantzari and how people ward them off using sprigs of holy basil until 6th Janary and the Blessing of the Waters when they are sent back underground, to find that in their absence the damage they had done to the Tree has healed itself. These plays are great fun for both the children and the visitors and make a nice counterpoint to the traditional nativity plays that are also performed.

Christmas Eve is the day for carols. Groups of schoolchildren go from door to door with little metal triangles, and occasionally other instruments, playing music and singing. When they knock, they usually ask: “Shall we say them?” There is a local traditional carol that is still very popular, that starts like this:

From a mansion we come,

and to a mansion we go

We will go to our Lord

May he live long

(English translation)

The children may instead choose to sing a modern song – a Greek translation of Jingle Bells or Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Whatever they sing, they are rewarded with coins and Christmas sweets for their efforts.

Santa Claus in Greece is known as Ai Vasilis,or St Basil, and he comes at the New Year. In Alexandroupolis, his coming is heralded on New Year’s Eve by a wonderful street pantomime involving two people dressed as a camel, complete with hump, and a third person who wears a strange sheepskin suit that tapers to an almost triangular point above the head. This is the camel driver, and he chases the camel around, mock threatening it with a stick, to great hilarity from the spectators. While this is going on, a group of people dressed in traditional costumes and with traditional instruments put on a display of folk dancing. The camel and companion go around the dancers, sometimes directly in their path, but somehow it all works out and no one falls over. Some years, Ai Vasilis will put in an appearance and march through the town, followed by the camel and driver as he leads them away at the end.

Santa Claus in Greece is known as Ai Vasilis,or St Basil, and he comes at the New Year. In Alexandroupolis, his coming is heralded on New Year’s Eve by a wonderful street pantomime involving two people dressed as a camel, complete with hump, and a third person who wears a strange sheepskin suit that tapers to an almost triangular point above the head. This is the camel driver, and he chases the camel around, mock threatening it with a stick, to great hilarity from the spectators. While this is going on, a group of people dressed in traditional costumes and with traditional instruments put on a display of folk dancing. The camel and companion go around the dancers, sometimes directly in their path, but somehow it all works out and no one falls over. Some years, Ai Vasilis will put in an appearance and march through the town, followed by the camel and driver as he leads them away at the end.

All this takes place in the town centre and is free for everyone to go and watch and join in. Lots of people bring their children, and not only for the show. Barbecues are put out on the central street and the air is full of the smell of meat roasting. It could be chops or sausages, or souvlaki; little wooden skewers with cubes of meat on. Just the thing to warm you in the chilly December air. One thing is definitely clear: Greeks do not worry about providing a vegetarian option.

The festive season is brought to an end on January 6th, with what is known as the Blessing of the Waters. People gather at the local harbor to watch. Prayers are said, and a priest throws a crucifix into the sea as part of the blessing. A group of young men are ready and waiting. Despite the cold, they dive straight into the water to retrieve the crucifix, with honours and blessings going to the lucky one whose hand closes on it first.

Evros is a special place in Greece, and Alexandroupolis is its largest town. As such, people from all over the region have now settled there, bringing their customs with them, meaning that this is a great place to experience Evritika, or traditions of Evros all in one place.

If You Go:

♦ www.visitgreece.gr/en/mainland/alexandroupolis

♦ www.virtualtourist.com/hotels/Europe/Greece/Prefecture_of_Evros/Alexandroupolis-427719/Hotels_and_Accommodations-Alexandroupolis-TG-C-1.html

♦ There are some fascinating museums in Alexandroupolis, such as the Ecclesiastical Museum, not far from the town centre, and the Ethnological Museum, which, among other things, houses some early printed texts in Greek and displays of costumes through the ages.

♦ There are a number of hotels in the town centre, and a lot of places to eat. Seafood restaurants abound on the seafront, and there are also traditional tavernas and other eateries in the town centre, all very easy to find.

♦ In the evening, you can find bars with live music, as well as the quieter kind.

About the author:

Millie Slavidou is a writer and a translator. As well as being a frequent contributor to Jump Mag, she is the author of the InstaExplorer series for pre-teens, which takes young readers on a journey round the world, experiencing local cultures, traditions and languages along the way. jumpbooks.co.uk/category/millie-slavidou

Photo credits:

Thanks to:

♦ alexandroupolisnews.blogspot.gralexandroupolisnews.blogspot.gr – for the new year camel and theofaneia

♦ C. Williams – for the children in traditional costumes getting ready to dance

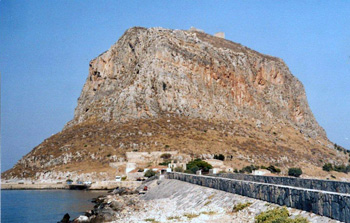

Yannis Ritsos was born in Monamvasia in 1909. An aristocrat by birth, renowned in Greece as an actor and director, he was one of Greece most beloved poets and is considered one of the five great Greek poets of the twentieth century. He won the Lenin Peace Prize in 1956 and was named a Golden Wreath Laureate in 1985.

Yannis Ritsos was born in Monamvasia in 1909. An aristocrat by birth, renowned in Greece as an actor and director, he was one of Greece most beloved poets and is considered one of the five great Greek poets of the twentieth century. He won the Lenin Peace Prize in 1956 and was named a Golden Wreath Laureate in 1985.

Lying on an important trade route, Monemvasia was occupied by the Venetians after pirate raids caused the inhabitants to ask for their help. There were 90 famous pirates in the Mediterranean at that time. After the Venetians took over, the town became inhabited with knights, merchants and officials. New building and restoration work began. But once Venetian power began to wane it fell to the Turks. When Turkey declared war on Venice, the city was recaptured but it wasn’t until the Greek War of Independence on July 21, 1821 that the town was liberated.

Lying on an important trade route, Monemvasia was occupied by the Venetians after pirate raids caused the inhabitants to ask for their help. There were 90 famous pirates in the Mediterranean at that time. After the Venetians took over, the town became inhabited with knights, merchants and officials. New building and restoration work began. But once Venetian power began to wane it fell to the Turks. When Turkey declared war on Venice, the city was recaptured but it wasn’t until the Greek War of Independence on July 21, 1821 that the town was liberated.

At the corner of Lysikrattis and Vironos Streets in Athens Plaka, stands a choreographic monument awarded to a choir at a Festival for Dionysos in ancient Athens’ Dionysos Theatre. Once, next to this monument, the last of its kind in Athens, was a French Capuchin convent. The poet, George, Lord Byron, stayed here when he was in Athens. At that time, the panels between the columns of the monument had been removed, so Byron used it as his study and wrote part of Childe Harold here in 1810-11. This was once the theatre district of ancient Athens, so it seemed appropriate that the flamboyant poet should choose to spend his time there. In Greek, “Vironos” means “Byron” and this is Byron’s street. I used to live there and spent much of my leisure time at the little milk shop, now a posh coffee shop, at that corner. The convent was destroyed in a fire, but there’s an inscribed monument on the spot where it once stood honouring Byron. His presence always seemed near.

At the corner of Lysikrattis and Vironos Streets in Athens Plaka, stands a choreographic monument awarded to a choir at a Festival for Dionysos in ancient Athens’ Dionysos Theatre. Once, next to this monument, the last of its kind in Athens, was a French Capuchin convent. The poet, George, Lord Byron, stayed here when he was in Athens. At that time, the panels between the columns of the monument had been removed, so Byron used it as his study and wrote part of Childe Harold here in 1810-11. This was once the theatre district of ancient Athens, so it seemed appropriate that the flamboyant poet should choose to spend his time there. In Greek, “Vironos” means “Byron” and this is Byron’s street. I used to live there and spent much of my leisure time at the little milk shop, now a posh coffee shop, at that corner. The convent was destroyed in a fire, but there’s an inscribed monument on the spot where it once stood honouring Byron. His presence always seemed near. The street adjacent, is Shelley Street, named for his poet colleague Percy Bysshe Shelly who tragically drowned in Italy. Both poets are honoured in Greece, especially Byron, who became a national hero when he joined the Greek resistance movement during the War of Independence.

The street adjacent, is Shelley Street, named for his poet colleague Percy Bysshe Shelly who tragically drowned in Italy. Both poets are honoured in Greece, especially Byron, who became a national hero when he joined the Greek resistance movement during the War of Independence. He lived for awhile on the island of Kefalonia (Cephalonia) in the tiny village of Metaxata, near Argostoli, where he enjoyed exploring the ruins of a Venetian castle at Ayios Yeoryios, once the Venetian capital of the island.

He lived for awhile on the island of Kefalonia (Cephalonia) in the tiny village of Metaxata, near Argostoli, where he enjoyed exploring the ruins of a Venetian castle at Ayios Yeoryios, once the Venetian capital of the island.

Life on Ithaka is quiet. There is no nightlife and very few buses run between the villages. Consequently, taxi drivers do a brisk business. Of the population of 2500, most are elderly and retired people. Most young people leave, preferring life in mainland cities for school and work. Those who do remain, mix agriculture with tourism, but the season is only for two months. The Ithakans want more tourism, but they hope to attract mainly a mature public who can appreciate the island’s unique history.

Life on Ithaka is quiet. There is no nightlife and very few buses run between the villages. Consequently, taxi drivers do a brisk business. Of the population of 2500, most are elderly and retired people. Most young people leave, preferring life in mainland cities for school and work. Those who do remain, mix agriculture with tourism, but the season is only for two months. The Ithakans want more tourism, but they hope to attract mainly a mature public who can appreciate the island’s unique history. Teams of archaeologists have been digging around the island, looking for evidence of Homer’s Ithaka and Odysseus’ Bronze Age city. I visit the Cave of the Nymphs where a team of American archaeologists and students are busy sifting and sorting through rubble brought up from a ten meter pit. This cave is believed to be the one where Odysseus hid the gifts given to him by the Phaecians when he returned home after his long, arduous voyage. There were originally two caves in two levels, but they have been collapsed by an earthquake. The cave has two entrances, so it fits the description in The Odyssey. Homer says it was a cave dedicated to the Nymphs. The cave has been used as a religious site, so in this way it fits with the Odyssey. These excavations may help identify the location of Homer’s Ithaka.

Teams of archaeologists have been digging around the island, looking for evidence of Homer’s Ithaka and Odysseus’ Bronze Age city. I visit the Cave of the Nymphs where a team of American archaeologists and students are busy sifting and sorting through rubble brought up from a ten meter pit. This cave is believed to be the one where Odysseus hid the gifts given to him by the Phaecians when he returned home after his long, arduous voyage. There were originally two caves in two levels, but they have been collapsed by an earthquake. The cave has two entrances, so it fits the description in The Odyssey. Homer says it was a cave dedicated to the Nymphs. The cave has been used as a religious site, so in this way it fits with the Odyssey. These excavations may help identify the location of Homer’s Ithaka. Is Ithaka the Homeric Ithaka? German archaeologists have claimed that the island of Lefkada is really the island Homer described. Why would Odysseus have his kingdom a small island such as Ithaka?

Is Ithaka the Homeric Ithaka? German archaeologists have claimed that the island of Lefkada is really the island Homer described. Why would Odysseus have his kingdom a small island such as Ithaka?