by Shelly Lachish

The ancient port of Acre (Akko in Hebrew, or Akka in Arabic), with its heavily fortified sea walls and imposing hilltop citadel, juts out defiantly from Israel’s coastline into the sapphire waters of the Mediterranean Sea. Standing at the city’s southernmost rampart, which is today equipped with a lighthouse and viewing platform, I cast my gaze over the golden fortress and down to the dramatic coastline where the waves break endlessly against the ancient sandstone walls that have withstood centuries of aggression.

For millennia, this mediaeval promontory, one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited locations, was a site of strategic military importance due to its commanding position on the trade route between Egypt and Syria. It is not surprising, therefore, that Acre’s history is a series of tumultuous invasions, defeats, victories and conquests that have played out over 1000’s of years by a multitude of conquering empires. Today, however, families of all nationalities and faiths live side by side in harmony in Acre, and the only shots heard over this UNESCO world heritage city come from cameras that belong to the army of tourists hungry to photograph this magnificent and intriguing historical site. Because even in this region of the world that teems with rich archaeological wonders, Akko stands out.

For millennia, this mediaeval promontory, one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited locations, was a site of strategic military importance due to its commanding position on the trade route between Egypt and Syria. It is not surprising, therefore, that Acre’s history is a series of tumultuous invasions, defeats, victories and conquests that have played out over 1000’s of years by a multitude of conquering empires. Today, however, families of all nationalities and faiths live side by side in harmony in Acre, and the only shots heard over this UNESCO world heritage city come from cameras that belong to the army of tourists hungry to photograph this magnificent and intriguing historical site. Because even in this region of the world that teems with rich archaeological wonders, Akko stands out.

Acre’s historical and archaeological intrigue lies in the fact that the forts, mosques, churches, synagogues and labyrinthine alleyways of the Old City that date back 350 years to the Arab and Ottoman periods, conceal below them an exceptionally intact 800 year-old Crusader city that has only recently been discovered. Leaving behind the city walls and the spectacular views of Haifa harbor that they offer, I begin my exploration of this ancient underground city by delving into the Templar Tunnel, a 350 meters underground passage that was constructed by knights of the Templar order and led from their own fortress to the port.

The tunnel, now restored and endowed with lighting, signage and a boardwalk alongside which rainwater flows freely to the sea, shrinks to just one meter in height before opening up to ground level at the resplendent Ottoman-built Pillar’s Inn (Khan Al-Umdan), a large multi-arched caravanserai, which was once the hub of international trade. From here, my explorations remain at ground level and lead me into the colorful Suk, the vibrant market street that forms the main thoroughfare of the Old City. It is midmorning and the market is crowded and bustling with activity as the locals attend to their shopping needs. Sweet stalls, vegetable stands, and shops selling clothing, ornaments, perfumes and other oriental artifacts, mix with bakeries, falafel shops, fishmongers and butchers stands, beneath which countless street cats make a healthy, if furtive, living. I amble slowly absorbing the sights and smells, and stop frequently to sample the delicious foods on offer.

The tunnel, now restored and endowed with lighting, signage and a boardwalk alongside which rainwater flows freely to the sea, shrinks to just one meter in height before opening up to ground level at the resplendent Ottoman-built Pillar’s Inn (Khan Al-Umdan), a large multi-arched caravanserai, which was once the hub of international trade. From here, my explorations remain at ground level and lead me into the colorful Suk, the vibrant market street that forms the main thoroughfare of the Old City. It is midmorning and the market is crowded and bustling with activity as the locals attend to their shopping needs. Sweet stalls, vegetable stands, and shops selling clothing, ornaments, perfumes and other oriental artifacts, mix with bakeries, falafel shops, fishmongers and butchers stands, beneath which countless street cats make a healthy, if furtive, living. I amble slowly absorbing the sights and smells, and stop frequently to sample the delicious foods on offer.

The market street snakes past the beautiful emerald-domed Al-Jezzar mosque and towards the main citadel complex where archaeological excavations allow the visitor to literally descend through the layers of history. At the modern, and mercifully well air-conditioned, visitor center, I rent an audio guide and embark on my own discovery of these fascinating ruins. I am guided aurally through the existing fortress building, an Ottoman fortification that was built on the foundations of the ruined Crusader citadel, and then down to the underground Prisoner’s Hall, where during the period of British mandate hundreds of members of Jewish resistance movements (Haganah, Irgun and Lehi) were held prisoner and even executed. The tour then descends further underground to the recently excavated Knights’ Hall comprising a series of long narrow chambers with ten meter high vaulted ceilings and massive dividing walls connected by great arched entrances. Also preserved in time are the remains of a dungeon, living quarters, and a mediaeval church. Tantalizingly, some of the rooms of this impressive feat of 13th century architecture remain roped off with teams of archaeologists and engineers busy with ongoing excavations: a promise of more exciting discoveries for future generations of tourists to behold.

The market street snakes past the beautiful emerald-domed Al-Jezzar mosque and towards the main citadel complex where archaeological excavations allow the visitor to literally descend through the layers of history. At the modern, and mercifully well air-conditioned, visitor center, I rent an audio guide and embark on my own discovery of these fascinating ruins. I am guided aurally through the existing fortress building, an Ottoman fortification that was built on the foundations of the ruined Crusader citadel, and then down to the underground Prisoner’s Hall, where during the period of British mandate hundreds of members of Jewish resistance movements (Haganah, Irgun and Lehi) were held prisoner and even executed. The tour then descends further underground to the recently excavated Knights’ Hall comprising a series of long narrow chambers with ten meter high vaulted ceilings and massive dividing walls connected by great arched entrances. Also preserved in time are the remains of a dungeon, living quarters, and a mediaeval church. Tantalizingly, some of the rooms of this impressive feat of 13th century architecture remain roped off with teams of archaeologists and engineers busy with ongoing excavations: a promise of more exciting discoveries for future generations of tourists to behold.

Ascending from the cavernous subterranean ruins of the Knights Hall I find myself at the entrance to the Hamam al Basha, a traditional 18th century Turkish bathhouse that remained in use until the 1940’s. Today the bathhouse has been reinvented as a light and sound experience in which a moderately humorous but slightly lengthy video presentation attempts to portray everyday life in the bathhouse culture. Despite the cheesy audio-visuals, the expertly restored, beautifully ornate bathhouse is well worth a visit. The entrance is a superb, domed-roof, marble room decorated with exquisite traditional ceramic tiles. A large marble fountain takes pride of place in the center of the room. At the base of the tiled walls there are small cavities, lockers of the past, which would one day have held the shoes and belongings of bathers. I take my sandals off and the chill of the 200-year-old marble floor feels wonderful on my weary feet. I proceed barefoot through a narrow corridor of smaller rooms where some of the more refined aspects of personal grooming and hygiene would have occurred, and into the main steam room – the social heart of the hamam. Here the domed ceiling has been perforated with geometrically placed holes through which hundreds of shafts of light penetrate to the raised marble massage area below. The dappled light is soothing and serene. Sculpted bronze figures and other relics placed around the large octagonal steam room help to recreate the authentic renowned feeling of communal relaxation for which the Turkish hamams were famous.

Ascending from the cavernous subterranean ruins of the Knights Hall I find myself at the entrance to the Hamam al Basha, a traditional 18th century Turkish bathhouse that remained in use until the 1940’s. Today the bathhouse has been reinvented as a light and sound experience in which a moderately humorous but slightly lengthy video presentation attempts to portray everyday life in the bathhouse culture. Despite the cheesy audio-visuals, the expertly restored, beautifully ornate bathhouse is well worth a visit. The entrance is a superb, domed-roof, marble room decorated with exquisite traditional ceramic tiles. A large marble fountain takes pride of place in the center of the room. At the base of the tiled walls there are small cavities, lockers of the past, which would one day have held the shoes and belongings of bathers. I take my sandals off and the chill of the 200-year-old marble floor feels wonderful on my weary feet. I proceed barefoot through a narrow corridor of smaller rooms where some of the more refined aspects of personal grooming and hygiene would have occurred, and into the main steam room – the social heart of the hamam. Here the domed ceiling has been perforated with geometrically placed holes through which hundreds of shafts of light penetrate to the raised marble massage area below. The dappled light is soothing and serene. Sculpted bronze figures and other relics placed around the large octagonal steam room help to recreate the authentic renowned feeling of communal relaxation for which the Turkish hamams were famous.

The audio tour ends and I surface from the relative cool and peaceful spaciousness of the bathhouse into the blinding heat of afternoon Mediterranean sunshine. Suddenly, the call of the muezzin sings resounds over the city, broadcast from speakers mounted at the top of Al-Jezzera mosque’s minaret. “Allah Akbar! Allah Akbar!” The distinctive melancholy melody calling the faithful to prayer casts an ethereal atmosphere over this mysterious city, and immediately transports me back to historic times. Undeniably, it is this combination of above ground beauty, hidden underground treasures, a thriving cultural life, and buried secrets yet to be discovered that ensures Acre will remain a living historical monument for years to come.

To the North of Israel Haifa Acre and Rosh Ha-Nikra Private Tour

If You Go:

♦ Acre is about 50 minutes’ drive from Haifa, or 1 hour and 45 minutes’ drive from Tel Aviv. Trains run every 20 minutes in peak times from either Haifa or Tel Aviv. There are also direct buses from Haifa and Nazareth to Acre.

♦ A full ticket entrance to the old city and the Turkish baths costs around $12 and includes the audio tour. Entrance to the Al-Jezzar mosque is extra.

♦ For more information: www.akko.org.il

About the author:

Shelly Lachish is an ecologist and freelance writer who has travelled extensively in Israel, Europe and Oceania. She currently resides in Oxford, England, where she moonlights as an academic. She blogs about her travels at thetravelaffair.net. This is her first contribution to Travel Thru History.

Photo credits:

All photos are by S. Lachish, and may be used under creative commons license.

The walled port city

The Pillar’s Inn (Khan Al-Umdan)

Women in the suk

Al-Jezzera mosque

Turkish bathhouse

Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem on a colt fulfilled the prophecy of Zechariah (Zechariah 9:9). As he descended the Mount of Olives, he stopped and looked out over the city. Jesus wept upon seeing the Holy Temple across the Kidron Valley (Luke 19:41-44) because he knew that Jerusalem would be destroyed – and it came to pass in 70 CE. This event is commemorated half way down the Mount of Olives where you find the “tear drop”-shaped Church of the Dominus Flevit (Latin for “the Lord Wept”).

Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem on a colt fulfilled the prophecy of Zechariah (Zechariah 9:9). As he descended the Mount of Olives, he stopped and looked out over the city. Jesus wept upon seeing the Holy Temple across the Kidron Valley (Luke 19:41-44) because he knew that Jerusalem would be destroyed – and it came to pass in 70 CE. This event is commemorated half way down the Mount of Olives where you find the “tear drop”-shaped Church of the Dominus Flevit (Latin for “the Lord Wept”). Entering the church, your eyes are immediately drawn to the arch-shaped picture window behind the altar. Those attending mass might be forgiven (hopefully) for being distracted by the magnificent view of the Old City of Jerusalem set within the window frame. The Dome of the Rock and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre are both conspicuous in this picture.

Entering the church, your eyes are immediately drawn to the arch-shaped picture window behind the altar. Those attending mass might be forgiven (hopefully) for being distracted by the magnificent view of the Old City of Jerusalem set within the window frame. The Dome of the Rock and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre are both conspicuous in this picture. Before he was betrayed, Jesus visited the Garden of Gethsemane to pray (Matthew 26:30, Mark 14:32, Luke 22:12, John 13:1). Located at the foot of the Mount of Olives, the Garden of Gethsemane showcases the Basilica of the Agony with its mosaic façade depicting Jesus as the mediator between God and man.

Before he was betrayed, Jesus visited the Garden of Gethsemane to pray (Matthew 26:30, Mark 14:32, Luke 22:12, John 13:1). Located at the foot of the Mount of Olives, the Garden of Gethsemane showcases the Basilica of the Agony with its mosaic façade depicting Jesus as the mediator between God and man. Inside the basilica, dark alabaster windows set the sombre mood for the agony and betrayal of Jesus. The flat “Stone of Agony” near the altar marks the spot where Jesus sweated blood (Luke 22:44) as he prayed. A mosaic behind the altar preserves that moment in time.

Inside the basilica, dark alabaster windows set the sombre mood for the agony and betrayal of Jesus. The flat “Stone of Agony” near the altar marks the spot where Jesus sweated blood (Luke 22:44) as he prayed. A mosaic behind the altar preserves that moment in time. Also on the site of the original Antonia Fortress, the Franciscan Monastery is located opposite the Al-Omariya School on the Via Dolorosa. This monastery houses both the Church of the Flagellation and Church of the Condemnation (the 2nd Station of the Cross).

Also on the site of the original Antonia Fortress, the Franciscan Monastery is located opposite the Al-Omariya School on the Via Dolorosa. This monastery houses both the Church of the Flagellation and Church of the Condemnation (the 2nd Station of the Cross). The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the holiest site in Christendom, is the traditional site of the crucifixion and tomb of Jesus. Enter the church and climb the well-worn stairs immediately to your right to the top of Golgotha/Calvary (Matthew 23:35, Mark 15:22, Luke 23:33, John 19:17). Here you enter the Roman Catholic Chapel of the Nailing of the Cross – the 11th Station of the Cross.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the holiest site in Christendom, is the traditional site of the crucifixion and tomb of Jesus. Enter the church and climb the well-worn stairs immediately to your right to the top of Golgotha/Calvary (Matthew 23:35, Mark 15:22, Luke 23:33, John 19:17). Here you enter the Roman Catholic Chapel of the Nailing of the Cross – the 11th Station of the Cross. Join the line to enter the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre inside the Edicule – the 14th Station of the Cross. Inside you find a reconstructed slab on your right consisting of two marble stones. A vase with candles marks the spot where Jesus’ head once rested.

Join the line to enter the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre inside the Edicule – the 14th Station of the Cross. Inside you find a reconstructed slab on your right consisting of two marble stones. A vase with candles marks the spot where Jesus’ head once rested.

Set on a sheer hillside, the Church of St. Peter in Gallicantu is the traditional the site of the High Priest Caiaphas’ house. Jesus was brought before Caiaphas immediately after his arrest (Luke 22:54, Mark 14:54, John 18:24, Matthew 26:57). You can easily find this church by looking for the roof with a golden rooster set on top of a cross. The rooster identifies this as the site where Peter denied Christ three times before the cock crowed (Matthew 26:69-75, Mark 14:66-72, Luke 22:55-62, John 18:25-27) hence the name “Gallicantu” (Latin for “the cock’s crow”). A statue in the courtyard depicts the event.

Set on a sheer hillside, the Church of St. Peter in Gallicantu is the traditional the site of the High Priest Caiaphas’ house. Jesus was brought before Caiaphas immediately after his arrest (Luke 22:54, Mark 14:54, John 18:24, Matthew 26:57). You can easily find this church by looking for the roof with a golden rooster set on top of a cross. The rooster identifies this as the site where Peter denied Christ three times before the cock crowed (Matthew 26:69-75, Mark 14:66-72, Luke 22:55-62, John 18:25-27) hence the name “Gallicantu” (Latin for “the cock’s crow”). A statue in the courtyard depicts the event. The churchyard features a number of ruins including olive presses, a bath house and a stone stairway leading to the Pool of Silwan below. Jesus may have used this stairway as he walked from the Coenaculum to the Garden of Gethsemane by way of the Kidron Valley before his betrayal. Visitors also find a model of the Old City of Jerusalem during the 4th-6th centuries CE. The Temple Mount is conspicuously bare and remained that way until the Dome of the Rock was constructed in 691 CE after the Muslim conquest.

The churchyard features a number of ruins including olive presses, a bath house and a stone stairway leading to the Pool of Silwan below. Jesus may have used this stairway as he walked from the Coenaculum to the Garden of Gethsemane by way of the Kidron Valley before his betrayal. Visitors also find a model of the Old City of Jerusalem during the 4th-6th centuries CE. The Temple Mount is conspicuously bare and remained that way until the Dome of the Rock was constructed in 691 CE after the Muslim conquest.

Straddling the shore of the Dead Sea, Highway 90 takes you through some of the most breathtaking desert scenery in the Middle East. You could be forgiven if you simply traveled southward and made an occasional stop to photograph the sandy brown cliffs and wadis (valleys) seemingly flowing into the salty water at the lowest place on earth. However en route, you also pass the unobtrusive sites of Qumran and Masada whose presence are only betrayed by signs denoting the park entrances. Neither site is visible from the road so if you are preoccupied with the scenery, you might miss them. And that would be a shame.

Straddling the shore of the Dead Sea, Highway 90 takes you through some of the most breathtaking desert scenery in the Middle East. You could be forgiven if you simply traveled southward and made an occasional stop to photograph the sandy brown cliffs and wadis (valleys) seemingly flowing into the salty water at the lowest place on earth. However en route, you also pass the unobtrusive sites of Qumran and Masada whose presence are only betrayed by signs denoting the park entrances. Neither site is visible from the road so if you are preoccupied with the scenery, you might miss them. And that would be a shame. Masada has come to symbolize the tenacity of the modern state of Israel. Each year members of the Israel Defence Forces visit the ancient fortress and swear that “Masada shall not fall again”. But in 73 CE, Masada did fall after a prolonged siege. When the end came, 960 Jewish zealots chose death before slavery and committed mass suicide just hours before the Romans stormed the site.

Masada has come to symbolize the tenacity of the modern state of Israel. Each year members of the Israel Defence Forces visit the ancient fortress and swear that “Masada shall not fall again”. But in 73 CE, Masada did fall after a prolonged siege. When the end came, 960 Jewish zealots chose death before slavery and committed mass suicide just hours before the Romans stormed the site. Return to the top of the stairs and walk along the western casemate wall to the appropriately named Western Palace – the largest structure on the plateau. Built around a central courtyard, this palace houses the throne room. The floor features the remnants of a mosaic with floral and geometric patterns.

Return to the top of the stairs and walk along the western casemate wall to the appropriately named Western Palace – the largest structure on the plateau. Built around a central courtyard, this palace houses the throne room. The floor features the remnants of a mosaic with floral and geometric patterns.

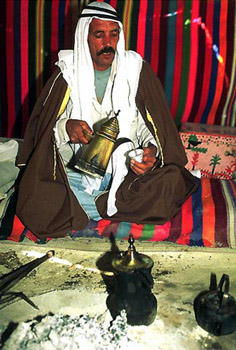

In 1947, a young Bedouin shepherd changed history when he threw a stone into a cave. Upon hearing the sound of shattered pottery, he climbed into the cave to investigate. Inside he discovered a number of earthenware jars containing 2000-year old parchment manuscripts. These documents, now known as the Dead Sea Scrolls, are some of the oldest Bible writings discovered to date. Eventually additional documents were also found in ten other caves, all of which are located near an isolated plateau holding the ancient village of Qumran.

In 1947, a young Bedouin shepherd changed history when he threw a stone into a cave. Upon hearing the sound of shattered pottery, he climbed into the cave to investigate. Inside he discovered a number of earthenware jars containing 2000-year old parchment manuscripts. These documents, now known as the Dead Sea Scrolls, are some of the oldest Bible writings discovered to date. Eventually additional documents were also found in ten other caves, all of which are located near an isolated plateau holding the ancient village of Qumran. Constructed of rough, brown stones and mud/clay mortar, all buildings at Qumran reflect the ascetic and communal lifestyle of the 200 Essenes living there. Believing that they were living in “the end of days”, their lives were focused on strict adherence to religious laws that included ritual bathing, voluntary poverty and an abstinence from worldly pleasures including marriage. Every day residents bathed before prayer and the noon meal. Dressed in white veiled clothing, each person descended steps and submerged himself into the cold water of a ritual bath (miqva’ot). Scattered around the village, ten ritual baths testify to the Essenes’ preoccupation with purity and ritual bathing. Ritual purity was so important that most of the baths had a division along the plaster-covered steps to prevent contact between those ascending (the purified) and those descending (the impure).

Constructed of rough, brown stones and mud/clay mortar, all buildings at Qumran reflect the ascetic and communal lifestyle of the 200 Essenes living there. Believing that they were living in “the end of days”, their lives were focused on strict adherence to religious laws that included ritual bathing, voluntary poverty and an abstinence from worldly pleasures including marriage. Every day residents bathed before prayer and the noon meal. Dressed in white veiled clothing, each person descended steps and submerged himself into the cold water of a ritual bath (miqva’ot). Scattered around the village, ten ritual baths testify to the Essenes’ preoccupation with purity and ritual bathing. Ritual purity was so important that most of the baths had a division along the plaster-covered steps to prevent contact between those ascending (the purified) and those descending (the impure).