Foremost among sacrificial donations was the human heart (tona), seat of the teyolia that moderns call the soul. It was believed to be a fragment of the sun’s fire (istli), the invisible seed of life that never dies. The instrument of sacrifice, the nahui tecpatl, was a knife divinized as a god, the implement of the Fifth Sun, used for heart extraction. It was a short six-to-eight-inch-long flint or obsidian double-edge blade with, for important ceremonies, a mosaic crouched figure of a god on the handle. The carved image shows circular plugs in its ears and a bow ornament made of feathers associated with Tonatiuh the Sun god; the figure’s hands appear to hold the knife’s blade. After a sacrifice, the water from cleaning the blood-encrusted blade and handle, was believed to produce a magical drink mixed with peyote (Lophophora williamsi), a psychoactive drug that was believed to make one contemptuous of death. Such a mixture was given to Eagle and Jaguar warriors going off to battle, and to noble captives led to the techcatl, the sacrificial stone. Standing about three to four feet high, and two feet or so wide with a sloped top upon which a captive was firmly held on his back. It stood about a foot from the front edge of the upper terrace of a pyramid so that the lifeless body could easily be tipped off to tumble down to the pyramid threshold, the apetlatl. “Heart extraction was a common form of sacrifice and was one of the most dramatic and grisly skills ever created by the imagination of man. The subject is unpleasant but, without at least a cursory knowledge of this practice, one can never know the Aztecs” (Brundage, 1979:215).

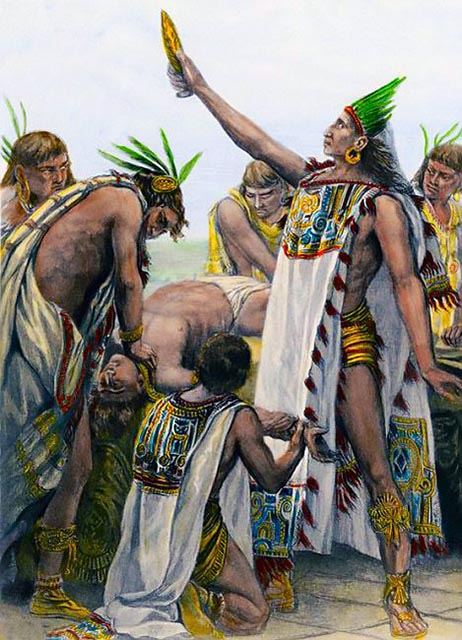

The sacrificial victim was forcefully brought up the pyramid’s steps by strong temple guards. On the Great Temple upper terrace, facing Huitzilopoltchli, the victim was met by the high priest and the priest-executioner. He was then forcefully stretched and held spreadeagled on his back on the techcatl by temple attendants (calmecacs). For religious sacrifices six souls were tasked to help release the seventh through the pain of deliverance. They were the five temple attendants, who each held the victim’s arms, legs, and head, the executioner was the sixth, and the sacrificed, the seventh soul. This symbolic order answered to the four Tezcatlipocas, lords of the four cardinal directions, together with those of the zenith and the nadir, with the victim on the techcatl at their intersection. Prayers and singsong incantations to the gods were attended with a low drumbeat.

Upon completion of invocations, the priest-executioner holding the sacrificial knife (nahui tecpatl), cut a deep eight-to-ten-inch lateral gash below the ribs on the left side of the rib cage. The screams of fear and pain coming from the victim were believed to please the deity. The priest then forcibly put his hand in the gash and, seizing the beating heart, ripped it out of the chest. The blood from the severed aorta and arteries gushed forcefully over the priest and his attendants. The high priest then lifted the heart above his head and sung praises to the god to whom the sacrifice was dedicated, attended by now louder drumbeats and conch shell trumpets. The heart, offered to the Sun was then thrown in a carved stone bowl (cuauhxicalli), shaped on the belly of the reclining stone statue of a man leaning on its elbows (chac mool); “later the heart was cooked and eaten by the priests” (Brundage, 1979:217). Once the heart was removed, the body was shoved from the blood-drenched sacrificial stone down the pyramid steep stairway of the pyramid and allowed to tumble to the bottom. There, it was seized by temple guards. The head was cut and taken to join others on the large skull rack (huey tzompantli), a tall rectangular structure erected on the plaza facing the Great Temple. The body was then cut to pieces and select parts were shared in a ritual cannibalistic feast by the captor (tlamanih), his family, and friends; a femur was given to the captor who hung it in his house as proof of his valor.

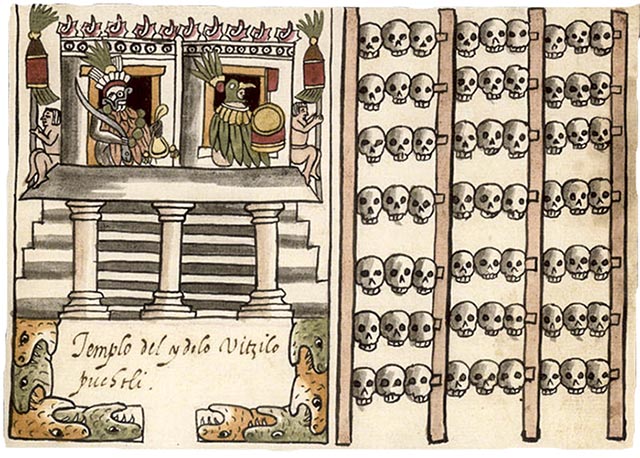

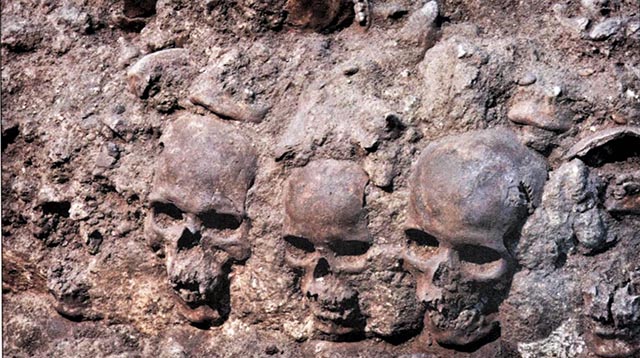

The skull rack facing the Great Temple was 115 long by 40 feet wide. On its top was erected a forty-plus foot high scaffold of wood poles connected by a series of smaller horizontal section of wooden crossbeams. The skulls had the skin and hair removed, except for those of nobles and army officers. They were then displayed on the tzompantli by punching holes through skull temples where the crossbeam pole was inserted. Display of skulls of war captives and other victims was meant to impress citizens and visitors alike. When the tzompantli ran out of room, old skulls were simply discarded. Why display only skulls and no other body parts? In ancient cultures the head, skull and brain were one and the same. It was perceived as the seat of physiological and emotional vitality, the locus of identity and social status.

The head was then believed to be the portal to the sacred and to life cycles. The central plateau of Mexico ancient records drawn by local people, point to thousands of sacrifices taking place each year in mid to large urban areas. In Cholula with its unusual number of temples, hundreds were sacrificed annually (Torquemada.II,120 – Acosta, 1962,). The great skull rack structure (tzompantli) in Tenochtitlan’s Great Temple precinct, was flanked by two tall towers in which were embedded hundreds of skulls. Between the towers the enormous lattice work of wood beams held thousands of skulls.

Taking war captives (yaoyotl) was very important to Aztec warriors. For common soldiers, social aspirations were tied to attaining emblematic status of “butterfly” (papalotl) by capturing four enemies for sacrifice, which would result in a promotion to officer rank. All the actors on a battle ground were aware that their foremost aim was to capture rather than kill the opponent. Enemies seriously wounded were dispatched on the spot, while others were taken behind the front line, by dedicated teams. Their hands were tied behind their backs and a wood collar (cuauhcozcatl), was fastened around their neck, and linked to a long rope tied on which other captives (maltin) were also tied. At the end of the battle, every enemy captured was brutally driven to the city limits where he was recorded and credited to his captor. Once inside the city, however, the captives were treated kindly and with deference, because, from this moment on, they were no longer captives or slaves but recognized as full-fledged Aztecs citizens, not foreigners. All their needs were met, and they were offered sumptuous garments, fine food, drink, and women, since as citizens, they were now the god’s properties preordained for sacrifice. For months they paraded in the streets, attended popular events, sang, danced, and were housed in nobles’ quarters. Civil servants, merchants (pochteca) and other notable people bought slaves they donated to their temple for sacrifice to their select deities. The Aztecs could not conceive of gods and their welfare without sacrificing their own, not foreigners, for these gods were their gods, not the gods of others. As noted by Garcia Icazbalceta, “no slaves were taken in the wars of these natives, for they kept them all for sacrifice, and such formed the majority of those sacrificed in the land. Few except those taken in war were sacrificed, for which reason wars were continual” (1824-1894).

Sacrifices increased with time, and Flower Wars (xochiyaoyotl) were dedicated to capture victims in time of peace. These so-called wars did not aim to gain political, military, or economic benefits, but to secure offerings for the gods. The parties fought under a set of agreed upon rules, among which was the presence of an equal number of well-trained fighters on each side. According to Ixtlilxochitl (1500-1550), a lord from Texcoco, the rationale for the Flower Wars arose in response to another enduring crop failure and consecutive famine due to a severe drought (1450-1454). According to Ixtlilxochitl, the high priests of the Triple Alliance, Tenochtitlan, Texcoco and Tacuba said that the flayed one Xipe Totec, the god of nature, was angry, and to placate his ire it was necessary for the affected communities to supply victims. Those, such as in Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, Tlaxcala, Cholula and Huijotzingo, among other cities, were mandated to obtain human sacrifices to appease the gods with lives and especially for the war god Huitzilopotchli patron of the state. In his old age, Tlacaelel referred to the Flower Wars as a military “fair” or “market,” arguing just as merchants went to distant places to purchase luxuries, the god accompanied the army to the Flower War to purchase the food, and drink he coveted. Sacrificed knights were understood to be the god’s food and blood, or the currency with which to purchase food for the deity (Assig, 1988).

The important site of the rain god Tlaloc, beside its sanctuary atop the Great Temple next to Huitzilopotchli’s at Tenochtitlan, was on the Tlaloc Peak (Tlalocatépetl) a 3,500-feet-high mountain on the eastern rim of the Valley of Mexico situated at the end of a forty-four miles road connecting the two places of worship. The Tlaloc Peak is located directly east of the Great Temple, in-line with classic Aztec architecture with sunrise, for the Mexica designed everything to cosmological directions. To appease the gods and deities of the water world and rain destructive forces, babies, and children up to eight years old were sacrificed there during dry periods until rains started. Young children were joyfully carried on open litter to the sanctuary atop the peak. At dawn for the Huey tozoztli celebrations, little boys and girls were decapitated to honor the gods Cinteotl, Chicomecoatl, Quetzalcoatl, and Tlaloc. Sacrifices also included starvation of the little ones when they were left in a small, sealed cave in which they slowly died. (Berrelleza, Torre Blanco – arqueomex. 1998:31). In 1980, in Mexico City’s Great Temple, at the northeast corner of Tlaloc’s temple, “Offering.#8” was uncovered where were found the decapitated remains of thirty-eight children of both genders aged two to seven years, sacrificed at the time of the 1450-1454 famine. Together with the remains were found turquoise disks, a Tlaloc effigy, jade necklaces, and other semi-precious jewels (Duverger, 2007:618). At the time, the depth of beliefs was so deep-seated in people’s mind and heart that it overcame elemental compassion for one’s own. In Mesoamerican cultures, in time of collective crisis, such as persistent droughts and repeated food shortage, a community would sacrifice its best and most cherished, not the sickly or the maimed. Sacrificial victims had to be able, in their prime, and the younger the better, for the gods would not accept anything less.

In other Mesoamerican cultures there were also numerous secular and religious holy days that required human sacrifices believed to pacify the deities of the cosmic order. But they never reached the extent found with the Aztecs. The constant emotional turmoil of endless wars drove common folks to suicide as found in codices, that show people strangling themselves. Were the people moved by deep religious convictions which required them to create public and private elaborate forms of individual spiritual cleansing and penance? A cursory reading of ancient texts in the nahuatl language, as Brundage points out, reveals the terrible anguish and fear of individuals because of offences against religious or moral laws (1979:186). For this reason, perhaps, collective cleansing events took place at dedicated times.

Prominent in the Aztec spiritual universe, was the end of the fifty-two-year calendar round associated with the 260-day sacred calendar (Tonalpohualli), and the 365-day agricultural calendar (Xiupohualli). The two-time cycles together created the 52-years Aztec “century” associated with the putting out and rekindling of fires throughout the empire. At that time, fires on temples and homes were extinguished. Ritual cleansing together with self-bloodletting by parents and children took place in each household. Ceramic bowls and plates, stone jars and cooking utensils were broken, for they were believed to carry the essence of the old cycle. Huehueteotl (aka Xiuhtecuhtlil) the lord of fire, was celebrated throughout the year but especially at the end of the fifty-two years cycles. For Huitzilopochtli was said to be in a constant struggle with darkness and required nourishment in the form of sacrifices to ensure the sun would survive the cycle of fifty-two years, which was the basis of many Mesoamerican myths. At that time, it was believed that the new fire ceremony would forestall the end of the Fifth Sun for it represented the shift from one time cycle to the following. Then, priests marched in solemn procession up the extinct Huixachtlan volcano to wait for Orion’s belt, called “the fire drill” to rise over the mountain; then a man was sacrificed. The victim’s heart was ripped from his body and a ceremonial hearth was lit in the cavity of the chest using the hand drill method to generate the sacred flame. A large wood pyre was then lit from that flame and torches were carried on pine sticks by runners to light the fires on temples in Tenochtitlan and beyond. The fires were also lit in homes and all family members drew blood anew from their nose or ears, and threw the blood-stained rags into the new fire, the smoke carrying their pleas and hopes to the gods. At dawn, the entire populace of a city or town would go to nearby bodies of water to wash and cleanse themselves of past anguish and despair.

It was during the reign of the eighth Tlatoani, Ahuitzol (1486-1502), that sacrifices knew no bounds. Ahuitzol inherited the throne after the short and weak rule of Tizok (1481-1486), who left serious problems unsettled with allies and foes alike, that required swift and forceful resolutions. Reasserting Aztec power was a major concern of the nobles for they depended on the income from Tenochtitlan’s tributaries, and it must have been a matter of significant concern for Ahuitzol as well. Tenochtitlan could ill afford another weak leader, and the fate of any such leader would probably be swifter than Tizoc’s but equally final (Assig, 1988:204). Upon his crowning Ahuitzol marched first into the Huastec region which had rebelled against Tenochtitlan but quickly came to its senses to avoid extermination. Then the army marched and conquered Cuextecs, Xolotan, Xiuhcoac, Tochpan, Tetzapotitlan, Nauhtlan and other city states (atlepetl), whose defenders were no match for the Aztec army. Many captives were slain on the field of battle, while thousands were captured and carried away to be sacrificed for the dedication of the sixth remodeling of the Great Temple in 1487. Ahuitzol’s coronation ceremony was treated with disdain by enemy states after Tizok’s tenure. The Tlatoani brutal military campaign, however, led rulers of allied and enemy cities alike to hurriedly flock to the temple dedication ceremony. To eradicate Tizoc weakness with friends and foes alike, Ahuitzol put on a frightening display of military power unprecedented in size with hundreds of captives reported sacrificed each day for weeks. The main beneficiary of the sacrifices was the god of war Huitzilopochtli, while other deities were provided with sacrificial victims on other temples.

The killing of so many did not allow time for a swift cut by the priests to retrieve the heart. Gone was society’s amity toward the prisoners that had prevailed when they were received at the city’s gates. The cries of pain and screams of terror arising from many temples kept residents shaken long after the killings stopped at nightfall. By midday, the temple guards had a hard time bringing the screaming and fighting victims up the temple’s steep slippery stairs, drenched as they were with blood. Because of the large number of victims, these were lined up in the streets leading to the temples to wait for execution, their hands tied behind their back and linked together by a rope passing through their nose septum (Assig, 1988:205). With the Aztecs reputation greatly restored through fear, Ahuitzol eased his control over internal matters.

Many cities received their newly appointed rulers in 1486, but others were not permitted home rule until 1488, while still others were deferred until 1493. On August 13, 1521, with the Aztec defeat at the hands of men from another world, the Sun set on the last Tlatoani, Moctezuma.II Xocoyotzin (1502-1520) and the ancient gods. Then another sun rose for the Mexican people.

This is Part Two of a Two-Part Article.

You Can Read Part One Here.

References – Further Reading:

Arqueología Mexicana:

Los Tlatoanis Mexicas – EE.40

Aztecas, Cultura y Vida Cotidiana – EE.75

Los Ejes de Vida y Muerte en el Templo Mayor y en el

Los Dioses de Mesoamérica – Vol.IV-20

Investigaciones Recientes en el Templo Mayor – Vol.VI-31

Plantas Medicinales Prehispanicas – Vol.VII-39

La Muerte en el Mexico Prehispanico – Vol.VII-40

El Sacrificio Humano – Vol.XI-63

La Guerra en Mesoamérica – Vol.XIV-84

Coyolxauhqui, Diosa de la Luna – Vol.XVII-102

Los Tzompantlis en Mesoamérica – Vol.XXV-148

Alfonso Caso, 1953 – El Pueblo del Sol

Padre Andrés de Olmos, 1530 – Historia de los Mexicanos por sus pinturas

Nigel Davies, 1987 – The Aztec Empire

Ross Hassig, 1988 – Aztec Warfare, Imperial Expansion and Political Control

Rebekah C. Bellum, 2015 – Narrative of Violence and Tales of Power

Broda, D. Carrasco, E. Matos Moctezuma, 1987 – The Great Temple of Tenochtitlan

Christian Duverger, 2007 – El Primer Mestizaje

John M. Allegro, 1970 – The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross

Anthony Aveni et al., 2023 – Aztec Myths and Legends

Nigel Davies, 1977 – The Toltecs, Until the Fall of Tula

Fray Diego Duran, 1569-1582 – Historia de las Indias de Nueva-Espana e Islas de Tierra Firme.

Berrin, E. Pasztory, 1993 – Teotihuacan

About the author:

Creative non-fiction writer, researcher and photographer, the author’s articles are about the history of the Americas before European arrival, their culture and beliefs. His articles are published online at travelthruhistory.com, ancient-origins.net and popular-archaeology.com, in the quarterly magazine Ancient American (ancientamerican.com), as well as in the U.K. at mexicolore.co.uk. The author is a fellow of the Institute of Maya Studies instituteofmayastudies.org Miami, FL and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org; as well as member in good standing of the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org, the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org, the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. americanindian.si.edu, and the NFAA – Non-Fiction Authors Association nonfictionauthrosassociation.com.

Contact: Georges Fery – 5200 Keller Springs Road, Apt. 1511, Dallas, Texas 75248, (786) 501 9692 –gfery.43@gmail.com and www.georgefery.com

Photo Credits:

Ph.08 – Seven Souls @PierreFritel artworks in commons.wikimedia.org

Ph.09 – Tecpatl, Sacrificial Knife @britishmuseum.co.uk

Ph.10 – Chac Mool, Tlaloc Temple @georgefery.com

Ph. 11 – Skull Rack, “Tzompantli” @arqueologiamexicana.mx

Ph. 12 – Skulls in Rack Towers @arqueologiamexicana.mx

Ph.13 – Huehueteotl, God of Fire @georgefery.com

Ph.14 – 2024, Mexico City Great Temple @georgefery.com

In San Ángel, the two artists fed, and bled, off each other. Medical problems plagued Frida, and her third pregnancy ended in yet another abortion. Diego had affairs, including one with Frida’s own sister, Cristina, resulting in a temporary separation. But Frida’s artistic and intellectual power also grew during this time, not only thanks to her husband, but also to the circle they drew around them. There, the surrealist André Breton recognized Frida’s talent and offered to show her work in Paris. Not long after, she gave her first solo exhibition at Julien Levy’s gallery in New York City. The San Ángel house was an incubator for both Frida’s talent and her misery. The two went hand in hand, as she painted portrait after portrait of herself in the form of an invalid and scorned woman, sad and withering away just as her star began to grow. Yet, through all this, Frida was slowly, but surely, becoming recognized for something more than her marriage to Diego Rivera. She was an artist in her own right, standing on her own two, albeit crippled, feet.

In San Ángel, the two artists fed, and bled, off each other. Medical problems plagued Frida, and her third pregnancy ended in yet another abortion. Diego had affairs, including one with Frida’s own sister, Cristina, resulting in a temporary separation. But Frida’s artistic and intellectual power also grew during this time, not only thanks to her husband, but also to the circle they drew around them. There, the surrealist André Breton recognized Frida’s talent and offered to show her work in Paris. Not long after, she gave her first solo exhibition at Julien Levy’s gallery in New York City. The San Ángel house was an incubator for both Frida’s talent and her misery. The two went hand in hand, as she painted portrait after portrait of herself in the form of an invalid and scorned woman, sad and withering away just as her star began to grow. Yet, through all this, Frida was slowly, but surely, becoming recognized for something more than her marriage to Diego Rivera. She was an artist in her own right, standing on her own two, albeit crippled, feet.

While Plaza San Jacinto is the neighborhood’s most popular outdoor space, the neighboring church (of the same name) provides a much more beautiful and calm place in which to rest. The Iglesia de San Jacinto was built in the 16th century, and feels almost lost in time. Both the building and its garden predate the Great Fire of London, with an architecture and sensibility that might be more at home in Italy, or France, than Mexico. The cloister feels Tuscan, the sanctuary Spanish. The garden is wonderfully wild, almost English in style, hidden behind large stone walls, yet easily accessible through both the church and a stone archway. It’s one of the most serene places in Mexico City, a beautiful spot to rest and contemplate, and begin to understand how truly ancient this country is, even in its colonial manifestations.

While Plaza San Jacinto is the neighborhood’s most popular outdoor space, the neighboring church (of the same name) provides a much more beautiful and calm place in which to rest. The Iglesia de San Jacinto was built in the 16th century, and feels almost lost in time. Both the building and its garden predate the Great Fire of London, with an architecture and sensibility that might be more at home in Italy, or France, than Mexico. The cloister feels Tuscan, the sanctuary Spanish. The garden is wonderfully wild, almost English in style, hidden behind large stone walls, yet easily accessible through both the church and a stone archway. It’s one of the most serene places in Mexico City, a beautiful spot to rest and contemplate, and begin to understand how truly ancient this country is, even in its colonial manifestations. Frida’s painting, The Two Fridas, tackles that very same subject, and dates from the years in which she lived in San Ángel. In the double self-portrait, a European Frida holds the hand of an indigenous Mexican version of herself. Even more importantly, their bloodstreams are connected by an artery flowing from heart to heart, bleeding out one end. In many ways, The Two Fridas is about acceptance – of Kahlo’s ancestry, and of Mexico’s—though it’s also about struggle, both in her understanding of her own personal identity, and of her marriage. It’s no accident that Frida needs to hold her own hand in the picture. The Two Fridas was painted just as her marriage was falling apart, and she divorced Diego for the first time.

Frida’s painting, The Two Fridas, tackles that very same subject, and dates from the years in which she lived in San Ángel. In the double self-portrait, a European Frida holds the hand of an indigenous Mexican version of herself. Even more importantly, their bloodstreams are connected by an artery flowing from heart to heart, bleeding out one end. In many ways, The Two Fridas is about acceptance – of Kahlo’s ancestry, and of Mexico’s—though it’s also about struggle, both in her understanding of her own personal identity, and of her marriage. It’s no accident that Frida needs to hold her own hand in the picture. The Two Fridas was painted just as her marriage was falling apart, and she divorced Diego for the first time. Despite the tragedy that surrounded their relationship, Frida’s San Ángel house is not an inherently sad place to visit. It’s architecturally interesting, and provides a hands-on, visceral glimpse into the two artists’ lives—a chance to see the furniture, books and giant papier maché dolls that filled Diego’s studio, and the ghosts that are left behind in Frida’s. Outside, tall cactuses grow like relics of a great pre-Columbian past, and purple Jacaranda trees frame Frida’s part of the building, which like her house in Coyoacán is painted a deep, vibrant blue. For all the pain and hardship she endured there, her resilience shines through.

Despite the tragedy that surrounded their relationship, Frida’s San Ángel house is not an inherently sad place to visit. It’s architecturally interesting, and provides a hands-on, visceral glimpse into the two artists’ lives—a chance to see the furniture, books and giant papier maché dolls that filled Diego’s studio, and the ghosts that are left behind in Frida’s. Outside, tall cactuses grow like relics of a great pre-Columbian past, and purple Jacaranda trees frame Frida’s part of the building, which like her house in Coyoacán is painted a deep, vibrant blue. For all the pain and hardship she endured there, her resilience shines through.

Over sixty years ago, two members of America’s Beat Generation did just that. First William Burroughs, then Jack Kerouac, came to Mexico City, searching for freedom, beauty and surreal inspiration in its storied, hallowed streets. They were drawn to a neighbourhood called “La Roma”, an enclave with a spirit that remains decidedly bohemian to this day, despite rising prices and gentrification spilling over from the neighbouring Colonia Condesa (“colonia” is the word that denizens of Mexico City, Chilangos, use for “neighbourhood”.)

Over sixty years ago, two members of America’s Beat Generation did just that. First William Burroughs, then Jack Kerouac, came to Mexico City, searching for freedom, beauty and surreal inspiration in its storied, hallowed streets. They were drawn to a neighbourhood called “La Roma”, an enclave with a spirit that remains decidedly bohemian to this day, despite rising prices and gentrification spilling over from the neighbouring Colonia Condesa (“colonia” is the word that denizens of Mexico City, Chilangos, use for “neighbourhood”.) La Roma is still the kind of place where a drag queen can live off the proceeds of her costume designs. Believe me, I met her. She lives in a small apartment off of Avenida Insurgentes and a red light shines from her window day and night, like a beacon, signalling to those who are wild and crazy and wonderfully artistic that they still can, unlike their Gringo counterparts, afford to live in a beautiful, central and historic neighbourhood.

La Roma is still the kind of place where a drag queen can live off the proceeds of her costume designs. Believe me, I met her. She lives in a small apartment off of Avenida Insurgentes and a red light shines from her window day and night, like a beacon, signalling to those who are wild and crazy and wonderfully artistic that they still can, unlike their Gringo counterparts, afford to live in a beautiful, central and historic neighbourhood. Today Calle Orizaba is one of the most beautiful in the neighbourhood, and the walk from 210 Orizaba north to the Insurgentes metro station is fantastic, taking you past historic homes, galleries, and the previously mentioned Plaza Luis Cabrera. It also passes the even lovelier Plaza Rio de Janeiro, where a replica of Michelangelo’s David towers above the square. Several intersecting streets are also worth exploring along the way, especially Colima and Durango, for their brightly coloured buildings, independent boutiques and art-filled watering holes. Casa Lamm, at the intersection of Orizaba and Alvaro Obregon is a cultural highlight, as is MUCA Roma on nearby Tonala street, a satellite gallery of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Located in an old historic home, it contains several floors of modern art, as well as one of the few free public washrooms in the area. These institutions are a testament to the dichotomy between historic preservation and gentrification that is now occurring in La Roma. On one hand they have kept art thriving and alive in the neighbourhood, and on the other, they have made it easier for businesses like American Apparel (Mexico City’s only outlet) to move in. It’s a double-edged sword, and you can pick your side amongst the al fresco dining options that surround nearby Plaza Rio de Janeiro. Orígenes Orgánicos, a corner café, represents the new, serving healthy vegetarian organic options on a private patio, bucking the trends in a country known for its love of meat. The dishes are not cheap by Mexican standards, about 90-120 pesos each (8-10 dollars), though they can provide welcome relief to travellers weighed down by a lack of plant-based options. For a new take on an old favourite, try their Nopales Huichapan: grilled cactus served with organic cheese, tomato and avocado. If you’re feeling more traditionalist, however, you can load up on birria tacos, made from stewed goat meat, around the corner for 6 pesos each, and eat them in the more democratic shade of the Plaza. Both are delicious.

Today Calle Orizaba is one of the most beautiful in the neighbourhood, and the walk from 210 Orizaba north to the Insurgentes metro station is fantastic, taking you past historic homes, galleries, and the previously mentioned Plaza Luis Cabrera. It also passes the even lovelier Plaza Rio de Janeiro, where a replica of Michelangelo’s David towers above the square. Several intersecting streets are also worth exploring along the way, especially Colima and Durango, for their brightly coloured buildings, independent boutiques and art-filled watering holes. Casa Lamm, at the intersection of Orizaba and Alvaro Obregon is a cultural highlight, as is MUCA Roma on nearby Tonala street, a satellite gallery of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Located in an old historic home, it contains several floors of modern art, as well as one of the few free public washrooms in the area. These institutions are a testament to the dichotomy between historic preservation and gentrification that is now occurring in La Roma. On one hand they have kept art thriving and alive in the neighbourhood, and on the other, they have made it easier for businesses like American Apparel (Mexico City’s only outlet) to move in. It’s a double-edged sword, and you can pick your side amongst the al fresco dining options that surround nearby Plaza Rio de Janeiro. Orígenes Orgánicos, a corner café, represents the new, serving healthy vegetarian organic options on a private patio, bucking the trends in a country known for its love of meat. The dishes are not cheap by Mexican standards, about 90-120 pesos each (8-10 dollars), though they can provide welcome relief to travellers weighed down by a lack of plant-based options. For a new take on an old favourite, try their Nopales Huichapan: grilled cactus served with organic cheese, tomato and avocado. If you’re feeling more traditionalist, however, you can load up on birria tacos, made from stewed goat meat, around the corner for 6 pesos each, and eat them in the more democratic shade of the Plaza. Both are delicious.

For a less trendy, more downhome perspective of La Roma, head to Roma Sur, which, for those of you who are Spanish-deficient, is the southern section of the neighbourhood. Centred around the Chilpancingo Metro station, Roma Sur is less pretty than its northern neighbour, but offers many cheaper, more authentically Latin American experiences. Right outside the Chilpancingo Metro station, on Avenida Baja California, La Espiga, a Mexican bakery, serves up delicious pastries for around five pesos, and fresh out of the oven Bolillos (buns) for even less. Walk a few blocks east and you hit Calle Medellin, home to Colombian restaurants and bakeries, and the Mercado de Medellin, a huge indoor market where you can do your produce shopping, buy fresh juice, or, if you feel like it, sit down to a delicious meal of chilaquiles con longaniza or enchiladas verdes for less than four dollars.

For a less trendy, more downhome perspective of La Roma, head to Roma Sur, which, for those of you who are Spanish-deficient, is the southern section of the neighbourhood. Centred around the Chilpancingo Metro station, Roma Sur is less pretty than its northern neighbour, but offers many cheaper, more authentically Latin American experiences. Right outside the Chilpancingo Metro station, on Avenida Baja California, La Espiga, a Mexican bakery, serves up delicious pastries for around five pesos, and fresh out of the oven Bolillos (buns) for even less. Walk a few blocks east and you hit Calle Medellin, home to Colombian restaurants and bakeries, and the Mercado de Medellin, a huge indoor market where you can do your produce shopping, buy fresh juice, or, if you feel like it, sit down to a delicious meal of chilaquiles con longaniza or enchiladas verdes for less than four dollars.