by: Georges Fery

This is the 2nd part of a two-part article. Read part one here.

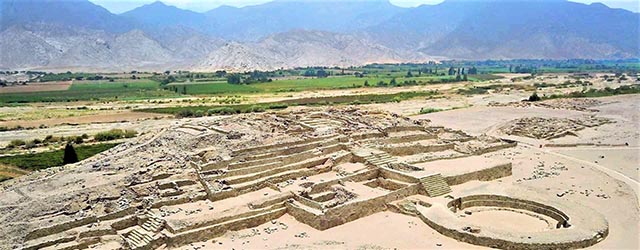

The Complex of the Amphitheater and its monumental circular sunken court is dated 2160BC. It is an important structure in the lower part (hurin) of the city, the counterpart to the Great Pyramid (hanan), but is not as commanding as the later. The walled complex is made of various components: a deck with a series of aligned cubicles; a large circular sunken plaza and a building with platforms that ascend sequentially. “On the east side of its perimeter is a circular altar and an elite dwelling. In the building were found several ceremonial hearths or Altars of the Sacred Fire, with their ventilation shafts built underneath. Buried in the circular sunken plaza of the Amphitheater were found 32 flutes finely carved from condor and pelican bones, as well as 37 bugles made of deer and llama bones, which point to the building’s ceremonial importance. They were “decorated with incised designs and painted with figures of local fauna and humans” (Shady, 1999b).

The main Altar of the Sacred Fire was found in an isolated area within the wall encircling the Amphitheatre complex. The religious ceremonies that took place there, as for most ancient agrarian societies, revolved around the powers of the sun, the moon, water, earth, celestial bodies, and their respective deities. This religious structure stems from the Kotosh religious tradition of the Late Archaic (4200BC) in the upper Andes, which influenced Caral religion through most of the millennium between 3000 and 2000 BC.

The priests were believed to draw their spiritual power from predicting cyclical natural events, such as the cycles of the sun the moon, and other heavenly bodies. For that reason, they were acknowledged as the anointed intercessors between people and the deities of nature. However, the priests lacked the scientific knowledge associated with their observations that would be acquired much later in time, so they merely acknowledged the repetition of those events that indeed appeared at predicated times. But what the priests could not predict were nature’s variables such as the intensities of the above-mentioned disrupters. At Caral as in most societies of the past, there was no separation between secular and creed for, as Shady notes, “religion was the nexus of cohesion and the ideology of the state acted as the instrument of domination of its government. Most of the activities carried out at Caral were, in some form or another, related to religious rituals and sacrifices” (1999a). The most important religious ceremonies may have taken place around the Altars of the Sacred Fire in the Great Pyramid, as well as in that of the Amphitheater. Less important ceremonies took place in other buildings. The shrine for the Sacred Fire is often made of a small circular platform with a fire pit in which small offerings were burned, such as those found at Kotosh.

The circular platform of the Sacred Fire was enclosed in a low quadrangular six-foot-high wall open space with access for only one person, most probably the high priest. A ventilation duct was built underneath the hearth that led the heat and smoke outside. In the shrine, the high priest called on natural forces and their deities to ascertain the timely arrival of natural events such as rains, winds, or other phenomena, and their consequences on crops. Planting and harvesting were daily concerns for most societies of the past associated, as they were, with the weather, rain specifically.

Delayed rains, or their diminished downpour, could translate into a bad or no crop at all, and the consequences: famine, the return of fear, and death. So the priests had to assure the city’s elite that the gods indeed helped in understanding nature’s hidden behavior.

Two other prominent architectural features at Caral are the large sunken circular courts built at the foot of the monumental staircases of the Great Pyramid and the Pyramid of the Amphitheater. They were used, as were the Maya rectilinear ball courts, for multi-function events at dedicated times. Religious ceremonies were likely prominent to celebrate major events such as spring and autumn equinoxes, the Austral solstices and the rising and setting of stars and planets mythologically associated with gods, deities, and seasonal celebrations, such as planting and harvesting. The discovery of finely carved flutes and bugles beneath the Pyramid of the Amphitheater’s sunken court, point tos the importance of musical instruments used during ceremonies and pageants. Remains of drums have not been found, so far, for their material may not have survived the test of time. Drums or percussion instruments, however, are recorded far back in time as the oldest device used by most cultures. Secular games may have taken place in the arena-like courts to celebrate social and sport events, an answer to ingrained human needs to compete in a controlled environment.

Through history, the universal use of games for secular or ritual purposes, underscore a commitment to maintain peace and balance between communal factions. Essential to ritual games, and to a certain extent secular games as well, was the need to keep in check latent antagonism within the same polity, as well as between polities.

In several buildings, archaeologists found human burials, mainly of children or young adults that are generally associated with specific rituals. As Shady points out, “the discovery of the body of a young man, deposited among stones that were used in an atrium in preparation for the construction of a new one, demonstrate this concept. The body was found above a layer of soil and stones, covered with other stones and the floor of the new atrium. It was nude and had no offerings except for the careful arrangement of the hair. Forensic analysis by Dr. Guido Lombardi indicates that it was a male of about twenty years of age, who was subjected to hard labor for most of his short life. He had received two forceful blows, one to the face and the other to the head (which was the cause of death); some of his fingers were placed in one of the niches of the temple” (2002). The remains of children were found underneath the floor of dwellings. This burial practice, as found in later cultures, was related to the belief that such offerings would contribute to the long life of the building.

Also found in residences were Quipus, the knotted strings made of camelid fibers such as llama or alpaca wool. Quipus were used, from the Late Archaic or probably earlier, as recording and communication devices arranged on a base ten positional system. The ones identified at Caral are among the oldest found in Peru. Furthermore, small low fired ceramic figurines – on average: five high by two inches wide – were found in secular and religious contexts. Their similarity with those of the San Pedro’s phase of the Valdivia culture of Ecuador (2700 BC), is striking.

The small Caral figurines are low fired with red and gray colors applied. The arms of the figurines, like those at Valdivia, are usually short and bent toward the chest or placed under the chin. In the Americas, diffusion of ceramics took place over a long span of time and across extensive geographical areas through trade, and some found their replicas at Caral.

The floor plans of residential houses vary according to their proximity to a pyramid complex, a direct reflection of the status of their residents. Their architecture is similar in both upper and lower Caral and, as for collective structures, are built of rocks set with mud. The largest household complex in Caral is found in Sector.A, in the upper half of the city (hanan). The quadrangular houses are built with a main entrance at the front and a door at the back, the later perhaps used for the kitchen or other services. Their sizes vary from 530 to 860 square feet, and they had interconnected rooms, also an indication of the status of a household. In several rooms small platforms and benches (beds?) were found. The walls and floors were covered with white, beige, or light-grey colored plasters, while those with red and yellow paints may indicate that they were the homes of the Caral elite” (Shady, 1997).

The central point still argued today about the diffusion of Peruvian cultures is whether it initiate from the coast, with its bountiful marine resources, or from the Andes Mountains to the Pacific Coast. In the view of archeologists Jonathan Haas and Winifred Creamer, “a complex society arose in Peru, thanks to irrigation agriculture, the same way it did in the world’s five other “pristine” civilizations, Mesopotamia, ca. 3500 BC, Egypt, ca. 3000 BC, India, ca. 2600 BC, China, 1900 BC and Mexico, ca.1200 BC (2005). Historian Karl Wittfogel points out that “irrigation was the catalyst that transformed tribal societies into city-states; for it required forced labor, central planning, a managerial elite, and provided the excess food necessary to support workers and administrators.” (1957). At Caral, the state government was sustained by dynamic diversified crops and a fishing economy. “Its sphere of domination and control included the populations of the Supe, Pativilca and Fortaleza valleys.

However, its connections and prestige extended across the entire north-central Peruvian region” (Shady, 2005). Social groups shared water through five ecological zones. The rivers begin in the high Andean Altiplano and flow through the mountain’s piedmont and, ultimately, to the coastal plains and the Pacific Ocean, a topography that was at the core of Caral’s survival for over a thousand years.

Haas and Creamer raise a pertinent point about “how ancient South Americans made the leap from subsistence fishing to urban sophistication.” Their main argument: “If the exploitation of marine resources is the reason for cultural complexity, why don’t you get a string of these big, complex societies up and down the Pacific coast? You don’t.” Haas maintains that the Late Preceramic sites of Aspero and Banduria, “grew as complex as they did because they could trade with inland settlements that had been revolutionized by irrigation agriculture.”

It takes a complex society to undertake big public construction projects, and the consensus is that complexity sprang from mastering agriculture. Hunter-gatherers had neither the means nor the need to create social hierarchies. That process (which entailed the division of labor and the emergence of a managerial caste), got under way only after humans settled down to farm” (2005). However, Aspero at the mouth of the Supe River, may still reveal surprises since recent radiocarbon dating showed that the village, with its two large platforms and circular sunken courts, had flourished as early as 3033BC.

Caral and its neighboring communities in the Pativilca and Fortaleza valleys were abandoned between 1800 and 1600BC. Why? We are not sure, but archaeological and geological data point to the relentless onslaught of disrupters and their cumulative effects, which priests could not foresee. Geological data uncovered that an earthquake estimated at 7.2 on the Richter scale took place in about 1820BC and destroyed much of Caral and Aspero (Sandweiss et all., 2009). This major earthquake was most probably followed by successive tremors of various intensity over the following weeks and months and contributed to more unstable rock and mud slides into the valleys.

The damages may have been worsened by an El Niño event that came concurrently or followed closely the earthquake and its aftershocks. Remains of torrential rains and consecutive gravel and dirt slides from the surrounding hills found by geologists are testimonies to the destruction of agriculture, that clogged rivers and wells in the valleys. The mouth of the Supe River was heavily choked by sediments that, together with storms, gale force winds and ocean current shifts over months, built up a sand belt along the coast that, is to this is day, is referred to as the “Middle World.”

This situation exacerbated an already unstable food supply, for the shift in ocean temperatures with La Niña pushed schools of fish farther and deeper offshore. Worsening an already catastrophic situation were climate shifts and sands blown inland from the coast to agricultural fields in the valleys, further destroyed cultures and obstructed canals already damaged by rock and mud slides.

Furthermore, Caral’s neighbors on its north and south were likewise severely impacted by these disastrous events. Food shortage worsened to such an extent that, together with the loss of cotton, produce and fishing, the economy collapsed. The pleas and tears of Caral’s priests could not prevent nor help in such a tragic situation, and Caralinos had no alternative but to flee and seek refuge in less afflicted communities.

The powers of nature were harsh on Caral and, so it seems, were its gods and deities. Garcia-Acosta points out that disasters are “triggers and revealers that have been important catalysts of change for much of human history.” As people begin to rebuild their lives in the wake of calamity, “one of their pressing concerns is for closure, for people need to understand why things happened in order to seek ways to make sure it does not happen again” (2002). Under severe conditions, new religious ideas and new leaders often emerge that take cultures in new directions.

Further Reading:

Ruth Shady Solis, 2001 – The Oldest City in the New World

Jennings, J., 2008 – Catastrophe, Revitalization and Religious Change on the Prehispanic North Coast of Peru

Ruth Shady and Carlos Leyva, 2003 – La Ciudad Sagrado de Caral-Supe

Roxana Hernandez Garcia, 2015 – Caral: 5000 Años de Identidad

Jesús Sánchez Jaén, 2008 – Caral, la Cultura de las Plazas Circulares

Ruth Shady Solis, J. Haas, and W. Creamer, 2001 – Dating Caral, a Preceramic in the Supe Valley on the Central Coast of Peru (Science, 292).

Haas and M. Piscitelli, 2004 – The Rise of Andean Pre-Inca Civilizations

Ruth Shady Solis, 2006 – La Civilización Caral: Sistema Social y Manejo del Territorio y sus Recursos; sus Transcendancia en el Proceso Cultural

Eva Jobbova, Ch. Elmke & A. Bevan, 2018 – Ritual Responses to Drought: An Examination of Ritual Expressions

Arthur D. Faram, 2010 – A Geographic Study of the Ancient Caral, Peru

About the author:

Freelance writer, researcher and photographer, Georges Fery (georgefery.com) addresses topics, from history, culture, and beliefs to daily living of ancient and today’s communities of Mesoamerica and South America. His articles are published online at travelthruhistory.com, ancient-origins.net and popular-archaeology.com, in the quarterly magazine Ancient American (ancientamerican.com), as well as in the U.K. at mexicolore.co.uk. The author is a fellow of the Institute of Maya Studies instituteofmayastudies.org Miami, FL and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org. As well as member in good standing of the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org, the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org, the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. americanindian.si.edu, and the NFAA – Non-Fiction Authors Association nonfictionauthrosassociation.com.

Contact: Georges Fery – 5200 Keller Springs Road, Apt. 1511, Dallas, Texas 75248, (786) 501 9692 –gfery.43@gmail.com and www.georgefery.com

Photo Credits:

7 – The Great Pyramid and the Supe Valley courtesy of cordilleraviajes.com

8 – El Altar del Fuego Sagrado: Se.Xauxa, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

9 – Amphitheatre and sunken court courtesy of qosqoexpeditions.com

10 – Condor and Pelican Bone Flutes courtesy of noticiasdelaciencia.org

11 – Caral, Ceramic Figurines courtesy of enperublog.com

12 – Pyramids and Residences courtesy of incatrail.com

13 – Banduria, the Middle World © georgefery.com

Caral, an abandoned city eroded by time and windswept sand, holds twenty-five structures including six pyramids that are as old as the Step Pyramid in Egypt. More remarkably, this early civilization developed in complete isolation without the use of pottery, metalwork or writing, unlike its contemporaries in the ancient Near East.

Caral, an abandoned city eroded by time and windswept sand, holds twenty-five structures including six pyramids that are as old as the Step Pyramid in Egypt. More remarkably, this early civilization developed in complete isolation without the use of pottery, metalwork or writing, unlike its contemporaries in the ancient Near East.

Just across the plaza, the Huanca Pyramid, named for the nearby 2.15 meter high huanca stone whose edges are oriented to the cardinal directions, holds three rooms atop its 12.8 meter summit. These rooms may have been used for astronomical and ceremonial purposes.

Just across the plaza, the Huanca Pyramid, named for the nearby 2.15 meter high huanca stone whose edges are oriented to the cardinal directions, holds three rooms atop its 12.8 meter summit. These rooms may have been used for astronomical and ceremonial purposes. En route to our next destination, the Greater Pyramid, I fought back a sneeze as a sudden gust of wind raised a cloud of dust. Seen through the haze, the Greater Pyramid is the largest structure on site covering approximately four football fields. From a height of 19.27 meters (seven platforms), city officials oversaw all of the activities within the city.

En route to our next destination, the Greater Pyramid, I fought back a sneeze as a sudden gust of wind raised a cloud of dust. Seen through the haze, the Greater Pyramid is the largest structure on site covering approximately four football fields. From a height of 19.27 meters (seven platforms), city officials oversaw all of the activities within the city. After making quick stops at the Lesser Pyramid, Quarry Pyramid and Central pyramid, we returned to the lower section of the city to visit the Temple of the Amphitheater. Julio directed us to a bank of twelve cubicles lining the entry platform that once held the remains of burnt food offerings.

After making quick stops at the Lesser Pyramid, Quarry Pyramid and Central pyramid, we returned to the lower section of the city to visit the Temple of the Amphitheater. Julio directed us to a bank of twelve cubicles lining the entry platform that once held the remains of burnt food offerings. Deeper inside the temple complex is the Altar of the Sacred Fire. This cramped round space houses an altar with a two-level fireplace; an air duct runs beneath. This room was likely used for mysterious ceremonies that the general public was not privy.

Deeper inside the temple complex is the Altar of the Sacred Fire. This cramped round space houses an altar with a two-level fireplace; an air duct runs beneath. This room was likely used for mysterious ceremonies that the general public was not privy.

The town of Pisac (elevation about 9,500 ft) has a central market that is frequently visited by tour buses on their way to the ruins on the hills above Pisac. Most tours stop at the craft market and then head up to the ruins for the morning, and then move on down the Sacred Valley to other archaeological sites. From the town of Pisac, you can view the ancient Inca terraces far up on the steep hillsides. Looking up the steep slopes from Pisac, it is hard to imagine walking up the steep slopes of the mountains to labor making stone terraces and farm these remote and high fields, but evidently the Inca did it. In the ancient construction of the agricultural terraces included both normal stairs and stones inserted into the walls to allow them to move up through the terraces as they tended their crops on the high slopes.

The town of Pisac (elevation about 9,500 ft) has a central market that is frequently visited by tour buses on their way to the ruins on the hills above Pisac. Most tours stop at the craft market and then head up to the ruins for the morning, and then move on down the Sacred Valley to other archaeological sites. From the town of Pisac, you can view the ancient Inca terraces far up on the steep hillsides. Looking up the steep slopes from Pisac, it is hard to imagine walking up the steep slopes of the mountains to labor making stone terraces and farm these remote and high fields, but evidently the Inca did it. In the ancient construction of the agricultural terraces included both normal stairs and stones inserted into the walls to allow them to move up through the terraces as they tended their crops on the high slopes. The next morning after arriving in town, finding a place to stay and getting some food for the hike, we set out up the stairs leading from town to the first set of terraces. We headed through the market stalls selling colorful alpaca wool shawls, blankets and hats, stopping to barter and eventually buy some woolen hats to ward off the chill of the thin mountain air. Leaving the market by a small back street passing between mud wall compounds and heading towards the steep slopes at the edge of town, we walked over the cobblestones of a path which led up towards the first ascent into the terraces above the village.

The next morning after arriving in town, finding a place to stay and getting some food for the hike, we set out up the stairs leading from town to the first set of terraces. We headed through the market stalls selling colorful alpaca wool shawls, blankets and hats, stopping to barter and eventually buy some woolen hats to ward off the chill of the thin mountain air. Leaving the market by a small back street passing between mud wall compounds and heading towards the steep slopes at the edge of town, we walked over the cobblestones of a path which led up towards the first ascent into the terraces above the village.

Fortunately, we had been at high elevations for over a week to allow our bodies enough time to adjust to the elevation and thin mountain air, so the climb did not cause any altitude sickness. As we steadily climbed the hill, breathing heavily as we strained to extract oxygen from the cool and crisp morning air, we climbed a long series of stairs up between two small guard towers. We continued through the high farm terraces and into the ruins of small settlement on the steep slopes where the buildings had been laid out to form the shape of a bird when viewed from above. Then we climbed up to the ceremonial center of Intihuatana within the ruins.

Fortunately, we had been at high elevations for over a week to allow our bodies enough time to adjust to the elevation and thin mountain air, so the climb did not cause any altitude sickness. As we steadily climbed the hill, breathing heavily as we strained to extract oxygen from the cool and crisp morning air, we climbed a long series of stairs up between two small guard towers. We continued through the high farm terraces and into the ruins of small settlement on the steep slopes where the buildings had been laid out to form the shape of a bird when viewed from above. Then we climbed up to the ceremonial center of Intihuatana within the ruins. From the ceremonial center, we moved up through an Inca tunnel carved into the rocky mountain top, along a defensive wall beneath military barracks (where they guarded the main entrance) and into a saddle that had sacred baths and views of cliff sides with burial caves in them. Since the caves have been hit by grave robbers, tourists are not allowed into that area. We finished by going to the tour bus drop off area to get a some fresh squeezed orange juice before heading back down into town. In addition to the sense of accomplishment from having climbed all the way up (11,200 feet above see level) from town (over 1,700 feet of elevation gain) we got to visit the site in the opposite direction as the flow of the tour groups, and we could not help but feel a little smug as tourists huffed and puffed their way back to the bus parking area after their short tour, loudly complaining about the short hike.

From the ceremonial center, we moved up through an Inca tunnel carved into the rocky mountain top, along a defensive wall beneath military barracks (where they guarded the main entrance) and into a saddle that had sacred baths and views of cliff sides with burial caves in them. Since the caves have been hit by grave robbers, tourists are not allowed into that area. We finished by going to the tour bus drop off area to get a some fresh squeezed orange juice before heading back down into town. In addition to the sense of accomplishment from having climbed all the way up (11,200 feet above see level) from town (over 1,700 feet of elevation gain) we got to visit the site in the opposite direction as the flow of the tour groups, and we could not help but feel a little smug as tourists huffed and puffed their way back to the bus parking area after their short tour, loudly complaining about the short hike.

The very Spanish-looking Plaza de Armas was once surrounded by Inca palaces but now it is a holy square. The Cathedral, flanked by two lesser churches, is the focal point. The conquerors disassembled the Palace of Viracocha and re-used its gray stone blocks in the Cathedral as walls and supporting columns.

The very Spanish-looking Plaza de Armas was once surrounded by Inca palaces but now it is a holy square. The Cathedral, flanked by two lesser churches, is the focal point. The conquerors disassembled the Palace of Viracocha and re-used its gray stone blocks in the Cathedral as walls and supporting columns. The cathedral also contains over 400 colonial paintings. The most interesting is “The Last Supper” where the main course is guinea pig and a local corn beer called chicha. At the bottom of the painting, to the right of center, Conquistador Francisco Pizarro sits as Judas.

The cathedral also contains over 400 colonial paintings. The most interesting is “The Last Supper” where the main course is guinea pig and a local corn beer called chicha. At the bottom of the painting, to the right of center, Conquistador Francisco Pizarro sits as Judas. Novice nuns were trained at the monastery until 1960. Their bedrooms were filled with personal furnishings that they were expected to provide for themselves as a condition of entry into the Order. Two-foot long cords were hung near their personal crucifixes suggesting that self-flagellation was fashionable at one time.

Novice nuns were trained at the monastery until 1960. Their bedrooms were filled with personal furnishings that they were expected to provide for themselves as a condition of entry into the Order. Two-foot long cords were hung near their personal crucifixes suggesting that self-flagellation was fashionable at one time.

More recently, part of the cloister crumbled during an earthquake thereby exposing four of the original Inca chambers within Qoricancha. The cyclopean walls are striking because of the carefully interlocking stonework. The Incas did not use mortar so as to provide the walls with greater flexibility during an earthquake. This design appears to have functioned very well over time but it was not fool-proof. Past tremors have misaligned a number of stones situated in the upper section of one room.

More recently, part of the cloister crumbled during an earthquake thereby exposing four of the original Inca chambers within Qoricancha. The cyclopean walls are striking because of the carefully interlocking stonework. The Incas did not use mortar so as to provide the walls with greater flexibility during an earthquake. This design appears to have functioned very well over time but it was not fool-proof. Past tremors have misaligned a number of stones situated in the upper section of one room.