Czech Republic

by Emily Monaco

What do rock and roll music and the fall of the Iron Curtain have in common? In Prague, the answer is quite a bit.

I’ve always been fascinated by revolutions and rebellions, particularly in countries that I’m otherwise not that familiar with. There’s little more evocative of what makes a people tick than what makes them revolt… and the Velvet Revolution in Prague is no different. Which is why when I visited Prague for the first time, I set out to learn all I could about this revolution, seeking clues to this history in modern Prague.

Prague fell to a Communist Coup d’état in February 1948, known in Communist historiography as “Victorious February.” This set the stage for many years of cultural and historical development – development that, oddly enough, is frequently linked to a rock star who was living on the other side of the Atlantic at the time.

Many come to Prague to visit the John Lennon Wall, a wall technically belonging to the Knights of Malta that’s completely covered in graffiti devoted to Lennon. But how many people know what this emblem to one of Western music’s most important figures means to locals of Prague? I decided to find out.

A Museum and Mausoleum for Czech Communism

In order to understand Prague’s revolution, one must understand what led to it, and there’s nothing better than the Communism museum for this. The museum is full of exhibits of life under the regime, though one gets the feeling that it’s rather tongue in cheek, given the postcards devoted to life under Communism – “You couldn’t get laundry detergent, but you could get your brainwashed”; “It was a time of happy, shiny people. The shiniest were in the uranium mines.” That was my first clue that music had something to do with all of this dark history.

In order to understand Prague’s revolution, one must understand what led to it, and there’s nothing better than the Communism museum for this. The museum is full of exhibits of life under the regime, though one gets the feeling that it’s rather tongue in cheek, given the postcards devoted to life under Communism – “You couldn’t get laundry detergent, but you could get your brainwashed”; “It was a time of happy, shiny people. The shiniest were in the uranium mines.” That was my first clue that music had something to do with all of this dark history.

A fairly no-nonsense timeline is nevertheless available at the beginning of the museum, detailing how Prague eventually ended up under a Communist régime for several decades. But what’s more interesting, at least to me, are the exhibits that show what life was really like – school, daily life, shopping… — under Communism.

The exhibit ends with a video, images that we don’t have of other European revolutions that took place too long ago. Images of people marching along Wenceslas Square, calling out for freedom, for the end of Communism and the beginning of something new. And behind it all, a soundtrack for the ages. This was only the beginning of my discovery, but everything I encountered would point back to this video, this peaceful protest.

How Music Saved Their Souls

The Prague Spring came about in 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubcek was elected as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Reforms by Dubcek were intended to grant more rights to citizens, including loosening strict restrictions on media – for the first time, young Czechs could listen to the Beatles on the radio. That was one thing that surprised me as I wandered the Communist museum – how willing locals were to seek out their favorite rock groups from America, buying records on vinyl from Western Europe and listening to them in secret.

The Prague Spring came about in 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubcek was elected as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Reforms by Dubcek were intended to grant more rights to citizens, including loosening strict restrictions on media – for the first time, young Czechs could listen to the Beatles on the radio. That was one thing that surprised me as I wandered the Communist museum – how willing locals were to seek out their favorite rock groups from America, buying records on vinyl from Western Europe and listening to them in secret.

Unsurprisingly, the Soviets did not take Dubcek’s attempts in favor of change well. The country was occupied after failed negotiations, and non-violent resistance began throughout the country, lasting 8 months. Bear these non-violent resistances in mind – they’ll come back later.

1968 was an important year for other reasons linked not to politics but to music. Of course, in this case, it’s hard to separate the two. While some young Czechs were listening to the newly released “Revolution” B-Side of the Beatles’ “Hey Jude” single, others were listening to more works of rock and roll.

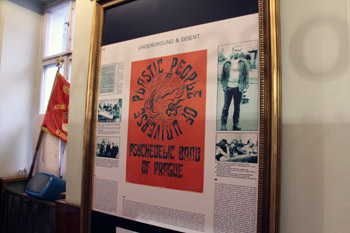

Inspired by the Velvet Underground, a group of Prague natives formed a band called the Plastic People of the Universe, just a month after the Prague Spring was suppressed by Warsaw Pact troops and just after Jan Palach, a philosophy student, set himself on fire on Wenceslas Square, issuing a warning before his death not to follow in his footsteps, a warning displayed on the walls of the Communism museum. The Plastic People played psychedelic garage rock typical of American FM stations of the time – led by front man Milan Hlavsa, a butcher by training, the group sang controversial songs of freedom, first in English, then in Czech. Their first studio album was called “Egon Bondy’s Happy Hearts Club Banned,” an ironic spin on poems by outlawed Czech poet Egon Bondy and the everpresent Liverpudlian Fab Four.

Inspired by the Velvet Underground, a group of Prague natives formed a band called the Plastic People of the Universe, just a month after the Prague Spring was suppressed by Warsaw Pact troops and just after Jan Palach, a philosophy student, set himself on fire on Wenceslas Square, issuing a warning before his death not to follow in his footsteps, a warning displayed on the walls of the Communism museum. The Plastic People played psychedelic garage rock typical of American FM stations of the time – led by front man Milan Hlavsa, a butcher by training, the group sang controversial songs of freedom, first in English, then in Czech. Their first studio album was called “Egon Bondy’s Happy Hearts Club Banned,” an ironic spin on poems by outlawed Czech poet Egon Bondy and the everpresent Liverpudlian Fab Four.

Nearly everything the Plastic People did was illegal in Prague at the time. It was hard to know what would be outlawed next – laughing in a cinema, singing English songs. Professional musicians were required to wear their hair short, but the Plastics wore their hair long. Their dark, subversive lyrics got them thrown in jail for years. And yet they kept playing… and people kept listening.

In 1970, the Communist government revoked the license for the Plastics to perform in public, forcing them to take the second part of the band title that had so inspired them literally – the Plastics were going underground. For years, they remained relatively off the radar, until 1976, when they played a music festival in the town of Bojanvovice, leading to arrests of all of the band members on charges of “subversive activities against the state.”

In 1970, the Communist government revoked the license for the Plastics to perform in public, forcing them to take the second part of the band title that had so inspired them literally – the Plastics were going underground. For years, they remained relatively off the radar, until 1976, when they played a music festival in the town of Bojanvovice, leading to arrests of all of the band members on charges of “subversive activities against the state.”

But nearly 10 years later, their message still pulsed throughout Prague. In 1989, Velvet was no longer Underground – evolving slowly from the moment that people like the Plastics first began to question authority, the Velvet Revolution had arrived in the city.

The Velvet Revolution – Resistance in Song

Marta Kubisova is just one of the many Czechs who was inspired by the “Hey Jude” single. The actress and singer first graced the public eye when “Prayer for Marta” became a symbol of national resistance in 1968, during the Prague Spring. And in the same year, when “Hey Jude” was released, Marta adapted it, releasing her own translated version in 1969 – the cover made her a local star.

Marta Kubisova is just one of the many Czechs who was inspired by the “Hey Jude” single. The actress and singer first graced the public eye when “Prayer for Marta” became a symbol of national resistance in 1968, during the Prague Spring. And in the same year, when “Hey Jude” was released, Marta adapted it, releasing her own translated version in 1969 – the cover made her a local star.

After a falsified pornography lawsuit, she was unable to work in many different places and ended up auditioning for the Plastic People of the Universe, a move disallowed by the secret police. On November 22nd, after several days of peaceful student protests and 20 years of having been banned from appearing in public, Marta sang “Prayer for Marta” from a balcony on Wenceslas Square.

Let peace continue with this country.

Let wrath, envy, hate, fear and struggle vanish.

Now, when the lost reign over your affairs will return to you, people, it will return.”

– “Prayer for Marta”

The biggest difference between the Velvet Revolution and any other revolution I’ve studied is the modifier: velvet. Stemming perhaps from a belief forged by the Plastics — that any dialogue with the totalitarian regime was futile and it was better to simply turn one’s back — the Velvet Revolutionaries did not fight for freedom, per se, but merely acted as though they were already free. The students walked. Marta sang. And it worked.

Revolution and Rock and Roll in Prague Today

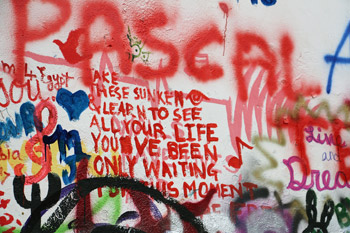

Today, the John Lennon wall still attracts hundreds of tourists, who come to look at the ever-changing paintings. The Knights of Malta have long since ceased trying to stop the graffiti. But while John Lennon is a meaningful symbol for many, it’s hard to understand just how much his music meant to young Czechs in the 80s.

Today, the John Lennon wall still attracts hundreds of tourists, who come to look at the ever-changing paintings. The Knights of Malta have long since ceased trying to stop the graffiti. But while John Lennon is a meaningful symbol for many, it’s hard to understand just how much his music meant to young Czechs in the 80s.

The wall first popped up in 1980, just after Lennon’s death, just a few years before Prague students took to the streets. The wall was created in memory of the man who, for them, embodied the freedom and liberation they so craved. “Lennonism,” then, a celebration of freedom and independence, became the counterpoint to Communism, and the evidence remains in Prague today, years after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

The wall first popped up in 1980, just after Lennon’s death, just a few years before Prague students took to the streets. The wall was created in memory of the man who, for them, embodied the freedom and liberation they so craved. “Lennonism,” then, a celebration of freedom and independence, became the counterpoint to Communism, and the evidence remains in Prague today, years after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

As I walk through modern Prague, I see music everywhere – folk metal bagpipe players on a central square, a lone guitarist in a fringed suede jacket playing a Beatles song. I find Wenceslas Square, finally, on one of my last days in Prague. It’s understated and small, hardly even labeled – it seems, to me, to be the perfect place for Velvet.

Skip-the-Line Museum of Communism Ticket and Prague City Private Tour

If You Go:

♦ Museum of Communism – Na príkope 852/10, 110 00 Praha 1

♦ National Museum – U Památníku 1900, 130 00 Praha 3 (The Music and Politics exhibit runs the end of March 2015)

♦ The Museum and Archive of Popular Music – Belohorská 201/150, 169 00 Praha

About the author:

Emily Monaco is a native New Yorker living in Paris. She earned a Master’s degree in 19th century French literature from the Sorbonne and now writes about revolution, cheese, and beer. Discover her experiences with Franglais and food on her blog, tomatokumato.com. Her writing has been featured in That’s Paris, an anthology about life in Paris.

All photos by Emily Monaco:

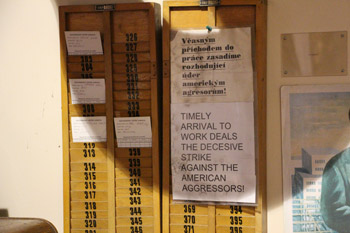

Communist anti-American propaganda at the Prague Communism Museum.

School under Communism as depicted at the Prague Communism Museum.

A hidden record player displayed at the Prague Communism Museum.

A Plastic People of the Universe poster.

The lyrics to “Blackbird” painted on the John Lennon Wall.

Paintings of John Lennon on the John Lennon Wall.

A folk metal bagpipe player busking in Prague.

A lone dog crossing an empty Wenceslas Square.

Wenceslas Square, one of the most legendary squares in Central Europe, in Prague, Czech Republic, has played host to a number of fitting names as well as false names. In tandem with the Czech people daily traversing its dark cobblestone, political subjugation in the 20th century led to cultural suppression and the great Wenceslas Square- named after a beloved Czech Saint and hero- was known momentarily by other names. Wenceslas Square (Vaclavske Namesti in Czech) was victimized by names and ideals forced upon it first by Adolf Hitler and then by Josef Stalin.

Wenceslas Square, one of the most legendary squares in Central Europe, in Prague, Czech Republic, has played host to a number of fitting names as well as false names. In tandem with the Czech people daily traversing its dark cobblestone, political subjugation in the 20th century led to cultural suppression and the great Wenceslas Square- named after a beloved Czech Saint and hero- was known momentarily by other names. Wenceslas Square (Vaclavske Namesti in Czech) was victimized by names and ideals forced upon it first by Adolf Hitler and then by Josef Stalin.

The bridge has also felt the steps of moved masses coming from Mozart’s premier of “Don Giovanni.” Perhaps the happy tempo of these steps felt similar to those that walked the bridge in 1918 when Czech people crossed it — citizens of a sovereign country for the first time in their long history.

The bridge has also felt the steps of moved masses coming from Mozart’s premier of “Don Giovanni.” Perhaps the happy tempo of these steps felt similar to those that walked the bridge in 1918 when Czech people crossed it — citizens of a sovereign country for the first time in their long history.

Then came The Devil. No one knows exactly when he first came, but everyone agrees it was over 10 years ago. On the edge of the bridge he set up shop where he thought he belonged, next to the other artists selling their creations to eager tourists in front of the Mala Strana tower.

Then came The Devil. No one knows exactly when he first came, but everyone agrees it was over 10 years ago. On the edge of the bridge he set up shop where he thought he belonged, next to the other artists selling their creations to eager tourists in front of the Mala Strana tower. Did he believe he was the devil? Why the Charles Bridge? Was it all a ploy for the money or was their some higher reason for what he did? I don’t know. And I won’t know. When I set out to find him and ask, he was not to be found. The other vendors informed me with long faces that he recently passed away.

Did he believe he was the devil? Why the Charles Bridge? Was it all a ploy for the money or was their some higher reason for what he did? I don’t know. And I won’t know. When I set out to find him and ask, he was not to be found. The other vendors informed me with long faces that he recently passed away.