Italy’s Emerald Coast

by Paola Fornari

“So where are you heading next?” the news agent asked, as he handed me my change and my postcards.

“Porto Cervo,” I replied.

“Why do you want to go there?” he asked. “That’s not the real Sardinia. You should stay here in Orgosolo, and explore further up into the hills.”

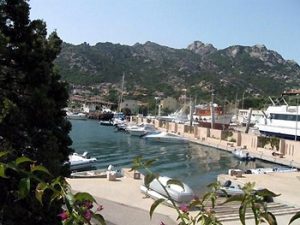

We had been planning a trip to Porto Cervo, the capital of Sardinia’s Emerald Coast – the Costa Smeralda – a thin strip of idyllic coastline on Sardinia’s north-eastern tip, seventy miles north of Orgosolo. The Aga Khan fell in love with the area in 1958, and bought it up, developing it into a designer-chic oasis for the rich and famous. That’s where we were heading. Instead, we took the news agent’s advice to explore ‘the real Sardinia’.

We had been planning a trip to Porto Cervo, the capital of Sardinia’s Emerald Coast – the Costa Smeralda – a thin strip of idyllic coastline on Sardinia’s north-eastern tip, seventy miles north of Orgosolo. The Aga Khan fell in love with the area in 1958, and bought it up, developing it into a designer-chic oasis for the rich and famous. That’s where we were heading. Instead, we took the news agent’s advice to explore ‘the real Sardinia’.

When we had begun our journey to Orgoloso earlier that day, driving up the mountainside, navigating narrow hairpin bends, my husband questioned the precarious journey.

“Are you sure this is wise?” he had asked.

I was engrossed in reading The Rough Guide: ‘ … bandit capital … between 1901 and 1954, Orgosolo – population 4,000 – clocked up an average of one murder every two months.’ Always the adventurer, I dismissed his worry. “Of course it’s wise,” I reassured him. “ The Guide wouldn’t recommend it if it wasn’t worth seeing. Oh listen, here’s another good bit: ‘… crime wave … lucrative practice of kidnapping … ’”

I must admit that as I read, I was becoming mildly anxious. Apart from the horror stories and scary sheer drops into the valley, there was a steady drizzle of rain and our battered hired car was struggling. But as this expedition had been my brainwave, I had to feign confidence and enthusiasm.

I must admit that as I read, I was becoming mildly anxious. Apart from the horror stories and scary sheer drops into the valley, there was a steady drizzle of rain and our battered hired car was struggling. But as this expedition had been my brainwave, I had to feign confidence and enthusiasm.

When we finally reached the town of Orgosolo, we had been relieved to find a few tourist coaches parked in the main square. It seems we had inadvertently taken the more tortuous of two eighteen-kilometre routes up from Oliena in the valley below. Tourists milled about, and there was an air of relaxed friendliness about the place. So we decided to stay. Orgosolo is an ugly town in a beautiful region called the Barbagia. The name is a corruption of Barbaria, which is what the Romans called the area, because even back in Roman times, the people had a reputation for being pretty fierce. It is close to the Supramonte, a high plateau dotted with caves and canyons.

Traditionally, shepherd communities inhabited the region, the men spending much of their time away from home with their herds. It is a poor area, and there was large-scale emigration after the war. Sheep-rustling was rife: poor shepherds would steal sheep from neighbouring villages, but never from their own. As in Calabria and Sicily, the people have developed their own way of dealing with disagreements and disputes, by-passing the authorities, and organised crime is rampant. In the early twentieth century a feud over inheritance lasted fourteen years and almost wiped out two entire families. Vendettas are still common today, happening usually around Christmas time, when families are gathered together. Usually victims are shot in the face, to prevent the families from being able to have open-casket funerals. We noticed that many local women were dressed in the traditional black clothing worn by women in mourning.

Traditionally, shepherd communities inhabited the region, the men spending much of their time away from home with their herds. It is a poor area, and there was large-scale emigration after the war. Sheep-rustling was rife: poor shepherds would steal sheep from neighbouring villages, but never from their own. As in Calabria and Sicily, the people have developed their own way of dealing with disagreements and disputes, by-passing the authorities, and organised crime is rampant. In the early twentieth century a feud over inheritance lasted fourteen years and almost wiped out two entire families. Vendettas are still common today, happening usually around Christmas time, when families are gathered together. Usually victims are shot in the face, to prevent the families from being able to have open-casket funerals. We noticed that many local women were dressed in the traditional black clothing worn by women in mourning.

In the middle of the 20th century, sheep-rustling was gradually replaced by kidnapping, which was found to be more lucrative. Initially the victims were wealthy local industrialists, but soon, high-profile holidaymakers became targets. They were hidden in the hills until their ransom demands were met.

The most well-known case was that of Farouk Kassam, a seven-year-old Belgian boy of Lebanese origin who in January 1992 was snatched by three masked gunmen from his holiday home in Porto Cervo. He was held for seven months in caves and hideouts. Part of his ear was sliced off and sent to his parents, in a bid to hasten the ransom payment. This triggered a wave of public revulsion, and a massive police hunt began. When he was reunited with his father, Farouk said ‘I didn’t cry.’

Graziano Mesina, known as ‘The Scarlet Rose’, Sardinia’s most notorious bandit, was pulled out of prison, where he’d been on and off for about half a century, to negotiate with the kidnappers, and was seemingly instrumental in the boy’s release, although the details are not clear. Some say a ransom of two million pounds was paid; the police deny this. Mesina was released from prison in 2004, and lives in Orgosolo with his sisters.

Graziano Mesina, known as ‘The Scarlet Rose’, Sardinia’s most notorious bandit, was pulled out of prison, where he’d been on and off for about half a century, to negotiate with the kidnappers, and was seemingly instrumental in the boy’s release, although the details are not clear. Some say a ransom of two million pounds was paid; the police deny this. Mesina was released from prison in 2004, and lives in Orgosolo with his sisters.

A local cult hero, Mesina’s romantic image was perhaps a little exaggerated. In 1960, unable to find his brother’s murderer, he found and killed the assassin’s brother instead. However, he was a Robin Hood-type figure, who robbed from the rich to give to the poor, and only killed those who betrayed him. Apparently, in the Sixties, he kidnapped a young boy, but repented only hours later, and released him, giving him money to buy chocolates on the way home.

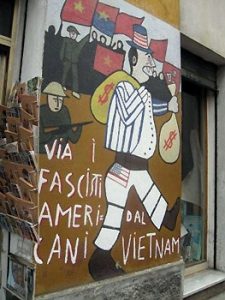

In 1975, to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Resistance and the liberation, the residents of Orgosolo decided they needed to improve the town’s reputation. They started decorating entire outside walls of houses and shop fronts with murals, many of them about the celebration. The town already had some murals dating back to the Sixties.

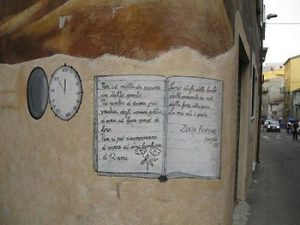

This new trend took off in a big way, and now the entire town is decorated with huge and beautifully executed Cubist-style frescoes, with subjects ranging from local political issues and the struggle of the peasant society, to 9/11, famine in Africa, or purely artistic trompe-l’oeils. Some are more recent, such as one depicting a letter from a child in Sarajevo, saying she is tired of the violence.

This new trend took off in a big way, and now the entire town is decorated with huge and beautifully executed Cubist-style frescoes, with subjects ranging from local political issues and the struggle of the peasant society, to 9/11, famine in Africa, or purely artistic trompe-l’oeils. Some are more recent, such as one depicting a letter from a child in Sarajevo, saying she is tired of the violence.

But the makeover was only cosmetic. Violence in Orgosolo has continued. In December 1998, a local priest, Graziano Muntoni, was shot dead for preaching against gun violence. His murderer is still at large. In December 2007, Peppino Marotto, a local poet in his eighties, was shot six times in the shoulders, and died, when he went to buy his morning paper. He was an unlikely target, a man who dearly loved and wrote about peasants, shepherds and brigands. But it seems that this was the end of a vendetta dating back fifty years. In typical Sardinian fashion, the locals clammed up. Marotto died on a busy street and strangely enough, or maybe not so strangely, no witnesses have come forward.

Perhaps, had I known all this at the time – rather more than the sketchy few lines provided by the Rough Guide – I may have answered a little differently to my husband’s ‘Is this wise?’ and insisted we go on to Porto Cervo. But then ignorance is bliss. There are plenty Porto Cervo-type glitzy resorts around the world, and they’re all pretty much the same, but there’s only one Orgosolo!

Barbagia Experience: Mamoiada and Orgosolo Day Tour from Cagliari

If You Go:

For a comprehensive site to learn more about Orgosolo history, accommodation and events, visit the Orgosolo, Sardinia online travel guide.

About Orgosolo:

– Population: 4779

– Area Barbagia di Ollolai, Sardinia

Sardinia Tourism website

About the author:

Paola Fornari was born on an island in Lake Victoria, and was brought up in Tanzania. She has lived in almost a dozen countries over three continents, speaks five and a half languages, and describes herself as an “expatriate sin patria”. Her articles have featured in publications as diverse as “The Buenos Aires Herald”, “The Oldie”, and “Practical Fishkeeping.” Wherever she goes, she makes it her business to get involved in local activities, explore, and learn the language, thus making each new destination a real home. She currently resides in Belgium.

Photo credits:

First Orgosolo mural photo by rbtraun from Pixabay

All other photos are by Paola Fornari.