A Scottish Effort to Colonize Eastern Panama in the late 17th Century

by Georges Fery

The conquest of the New World was devastating for its ancient cultures. Its aftershocks are still deeply felt today in communities across the Americas. Soon after Spain’s subjugation, other European nations tried to organize trade with her colonists or forcefully capture part of her new possessions. When foreign ships, among them were those of buccaneers and corsairs, succeeded in their penetration of Spain’s colonies, they returned to Europe with the rich spoils of the West Indies. Commercial ventures sprang up to trade or settle in those new lands. At the end of the 17th century, a Scotsman, William Paterson, devised a plan to establish a colony in Darien in eastern Panamá. In fact, it was no less than a filibustering expedition into Spanish America, with the aim of securing a foothold on the Isthmus. The plan was to control the passes over the central mountain range, with the goal of capturing a trade route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. A vision that flew in the face of reality given the two hundred years occupation of the isthmus by Spain.

William Paterson, a co-founder of the Bank of England and instigator of the Darien Scheme as it was called, was born in 1658 in Scotland. At seventeen, he was involved in a Presbyterian plot against the rule of King Charles II and had to run away from home. He went to Bristol, a port of infectious adventure and, at nineteen, he went to sea from there like the buccaneer Henry Morgan, to seek his fortune first in the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam and then in the English colony of Jamaica. When he came back ten years later, he was a wealthy man; he had also acquired an understanding of trade and high finance, together with a collection of maps and reports of Central America, no doubt acquired from the buccaneers calling in Jamaican ports.

The end of the 17th century was the only time when the Scots could have formed the national project of a colony, since at this time, Scotland was independent from England. The “seven ill years” of the 1690s saw widespread crop failure, famine and extreme poverty that may have killed ten to fifteen per cent of the population; Scotland was desperate. In the ninety years since the death of Elizabeth.I (1533-1603), the Scots had shared the English kings but had their own Parliament, except when Cromwell (1599-1658), brought them under English rule.

In the 1680s, there was no sign that Scotland would ever be capable of embarking on such grand design as the one proposed by Paterson. He took his idea to Germany and offered it to the trading cities of Emden and Bremen, but everyone turned him down. So, he came back to England and settled in London as a merchant and, at thirty-nine, took a leading role in founding the Bank of England.

The Darien Company

In 1683, Scotland’s Parliament passed the Act for Encouraging Trade, and on June 26, 1695, created “The Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies,” generally known as the “Darien Company.” Paterson, and the Company directors’ covert plan was to capture a foothold on the isthmus, to secure a gateway and control trade between the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. The company was given monopoly of trade for 31 years and freedom of taxation for 21. Paterson was named a director. On November 13, 1695, Paterson and his co-founders raised the capital for their venture; half of it in London, the other half in Scotland.

The East India Company took alarm at the prospect of a Scottish rival and petitioned the House of Commons. Political pressure led the king to withdraw his already lukewarm support for the Darien Company, and the whole London stock issue had to be withdrawn. It was sold in Scotland; every Scotsman with a hundred pounds rushed to invest. That is when Paterson revealed his dream to his fellow directors and showed them his maps and reports from Darien; they were captivated by his plans. But at that time, England was at peace with Spain, and the English were forbidden to supply ships or sailors so the Darien Company was forced to order five ships to be built in Hamburg and Amsterdam. Large stocks of supplies and trade goods were purchased, which were stored in warehouses in Edinburgh.

The board of directors sent Paterson to Hamburg to pay for five ships and their equipment. He deposited the money with James Smyth, that proved to be an untrustworthy merchant friend in London. This led to a tragedy that had dire repercussions, and from which Paterson never recovered. To get a better rate of exchange, he was robbed of £17,000 by Smyth, of which £9,000 were later recovered. The investigation committee ultimately cleared Paterson of any wrong doings but held him morally responsible for the loss. He was told that he still could go on the expedition but only as a volunteer, without any official capacity or authority.

In November 1697, the five ships arrived in Leith Roads, Scotland, and wintered in the nearby Firth of Forth. In March 1698, the Company selected about 1,200 individuals, of which 60 were ex-army officers and soldiers; there were few women among them. At that time, a famine in Scotland pushed people to seek their fortune in faraway lands, and far more Scots volunteered than could be accepted. However, there was still no mention of Darien or any other destination. On July 17, 1698, the fleet set sail, taking the highest hopes of Scotland with it. The captains had received sealed orders, which they were to open in Madeira. Not a soul on board the ships, except for Paterson, knew for certain where they were going.

The five ships were the St. Andrew, the Unicorn, the Caledonia, the Endeavour and the Dolphin; the first three were armed merchantmen of forty-six guns, the last ones were tenders. Paterson was on board the Unicorn and traveled as a simple planter. Upon opening their sealed orders, the captains proceeded to a sandy bay southeast of Golden Island, off the coast of Darien, where they dropped anchor in a protected bay on the morning of October 30, 1698, they named it Caledonia Bay. The port was well sheltered from the sea by a long peninsula, where the Scots selected the site of New Edinburgh for their settlement. A battery of 16 guns was erected to command the harbor they called Fort St. Andrew.

Across the bay was the deserted Spanish settlement of Acla founded by order of the Governor of Castilla de Oro, Pedro Arias Dávila, in 1515. Acla was then to be the Atlantic anchor of a trail leading to a future town on the Gulf of San Miguel, on the Pacific coast.

Spain was much alarmed by the invasion and settlement by other Europeans in its “Castilla de Oro” or Golden Castile territories. They remembered the raids of buccaneers on the isthmus by Francis Drake, twice: Nombre de Dios on the coast of Darien in 1572 and the sack of Panama in 1595, and then again by Morgan in 1671. The Spaniards realized that the Scots settlement close to Acla was not a random choice but one driven by a bigger plan than that of a trading outpost. The record shows that the Directors instructed the Council in Darien to purchase land on the Atlantic coast from the Indians as well as on the Pacific, “for certain reasons, of which you shall be acquainted with in due time.” The governor of Panamá and Cartagena gathered land and sea forces to evict the invaders. In December 1698, an English ship called on the colony and was able to report to England that the Scots were indeed carving a settlement in Spanish America, against the wishes of the Crown, then at peace with Spain. The king issued secret orders to the English colonial governors of America, forbidding them to trade, supply food or offer any assistance to the Scottish colonists.

In Darien a small group of Cuná Indians approached the Scotts settlement waving their unstrung bows, a sign of friendship, no doubt they learned the hard way from the Spaniards. The Scots told Pedro the headman, that they meant to settle in Darien if the Indians received them as friends. After two months, a turtle-hunting ship stopped over and the colonists took that chance to send their first report to the Company at home. The report reached Edinburgh in March 1699. All over Scotland, there was rejoicing and pride at the news of the colonists’ safe arrival, the Indians’ welcome and the verdant beauty of the country. At the very time the bells were ringing in Scotland, and prayers of thanksgiving were being offered in the churches, the colonists were faced with disaster.

The seeds of the ultimate tragedy had been planted by the stubborn ignorance of the Company’s directors. They had not only fitted the expedition out with a ludicrous choice of supplies and goods, and rejected Paterson, who was by far the wisest man at their disposal. They had appointed a council of seven men to rule the colony but had not appointed its president. It was to be run by a committee, the catastrophic effect of such decision was to deprive the colony of effective leadership.

A Heavy Price For Terrible Mistakes

In April 1699, the worst disaster hit them. It had started to rain. The settlers had arrived, by chance, at the beginning of the dry season, but now it was over. Their delight in the climate, which had at first seemed so healthful turned to disgust and horror. For the colony, Paterson had selected a site in the middle of the coast of Darien, because he believed there were no Spanish settlements there. The reason, of course, was that no European had ever been able to live for long there. The rainy season arrived and now, with pouring rains, the swamps steamed, the mosquitoes bred, and the Scotsmen paid a heavy price for their terrible mistakes.

Upon receipt of the first report of the colony, and while the directors in Scotland were rejoicing over the good news and anticipated profits, the Caledonians were preparing to leave Darien. The accumulation of troubles, very real and oppressing, and fears both justified and fancied, brought the colony into a state of panic. Furthermore, sickness among the colonist, attributed to “flux and fever” (yellow fever), aggravated by lack of food took a heavy toll, and about 400 of them had already died of diseases. On June 22, 1699, about eight months after landing, and having heard nothing from the company, the 800 enfeebled survivors evacuated New Edinburgh.

Each ship selected her own course to hasten away from the mortal bay. The St. Andrew reached Jamaica, losing 120 persons to sickness. Paterson was carried on board the Unicorn in delirium; his wife, her maid and his clerk had already died; this ship steered for New York, losing about 250 souls to diseases. In New York, they found the Caledonia which had arrived ten days before, having lost 150 people to the same causes. People that died in transit were perfunctorily buried at sea.

The story ought to have ended there, but it did not. It started all over again, simply because nobody on either side of the Atlantic knew what was happening on the other side. The directors fitted a small relief fleet with provisions made up of two ships, the Hopeful Binning of Bo’ness and the Olive Branch with 300 recruits. The small fleet sailed from Leith Roads on May 12, 1699. They found New Edinburgh deserted. A week after their arrival, a careless accident by a steward set fire to the Olive Branch, burning all supplies. The would-be settlers could not stay with the few supplies in the second ship, so about 12 Scots elected to stay in Darien, including the carpenter and his wife, while the rest boarded the remaining ship which sailed to Jamaica, where most of them died.

A third expedition was ready to sail in the Clyde in western Scotland, on August 18, 1699, four days after the Unicorn, from the first expedition, had crept into the port of New York. The news of the Colony’s desertion was on its way to Scotland, and if only it could have arrived in time, the new ships might have been reequipped and the old mistakes rectified.

The Caledonian Disaster

The four ships in the Clyde, packed with over 1,200 men and a few women, were delayed a whole month by contrary winds. Meanwhile, a ship was beating its way across the Atlantic bearing the news of the Caledonian disaster. It finally reached Bristol and a coach rumbled up the Great North Road to Edinburgh with the details. On September 22, 1699, while the fleet still waited, orders were dispatched to the fleet commander with new instructions. The captains, fearful of further delays and since that night the wind had changed course, disregarded their instructions. In less than twelve hours after receiving the orders, the fleet set sail at dawn on September 24, 1699.

This third expedition was the largest body of colonists sent to Darien and was called the Rising Sun Party. The four ships party were, the Rising Sun, the Company’s Hope, the Duke of Hamilton and the Hope of Boroughstomen. The Rising Sun Party reached Caledonia Bay on November 30, 1699 and was shocked to find New Edinburgh deserted. During the trip, 160 people perished, and once again all the old mistakes from the first expedition were repeated. Like the previous parties, things went rapidly from bad to worse. Time and again, the headless council overrode the most sensible advice made by knowledgeable people; its members fighting among themselves could not grasp the magnitude of their mission.

A sloop from Jamaica brought news of four Spanish men-of-war that had newly arrived from Spain to Portobello, a few miles from Caledonia on the Atlantic coast, and of three more expected from Cartagena. On February 13, 1700, Cuná Indians warned the colonists of a Spanish army approaching across the isthmus. Two days later, Captain Alexander Campbell and Lieutenant Turnbull, with two hundred Scots and forty Indians, clashed with the Spaniards and defeated them. Both Campbell, Turnbull and Chief Pedro were wounded while seven Scots were killed. The Caledonians were elated over the “successful” encounter, but their joy proved to be short lived, for this was only a skirmish. A few days later, on February 25, eleven Spanish men-or-war anchored within Caledonia Bay, in plain view of the settlement.

Following the interrogation of two Scottish deserter, the enemy landed troops at Caret Bay, two leagues to the west of the settlement, under the command of the Darien governor, Don Miguel Cordoñes. Spaniards, Creoles, and Choco Indians were reported coming from Panamá and others from Santa Marta. A few skirmishes left several Scots dead and wounded; they could not be replaced. In defiance of serious losses and the Caledonians’ bravery, the Spaniards advanced their line of battle to within a mile from the Scottish fort. They also captured small streams, a half mile from the settlement, where the colonists got their drinking water. There were no options but to surrender.

Articles of Capitulation

During the second meeting with the Scots on March 31, 1700, and their signing the Articles of Capitulation, the Spanish commander, Don Juan Pimienta governor of Cartagena and Panamá, gave the Scots fourteen days to prepare for sea and leave Darien. The capitulation terms were favorable to the Scots allowed to retain their weapons and leave with drums beating and colors flying. The Cuná Indians were included in the Seventh Article that specified that they would not be molested following the Scotts’ withdrawal.

Early in the morning of April 11, 1700, the sixty-gun ship Rising Sun, was helped by a Spanish ship out of a wind locked Caledonia Bay. The following day, the three other vessels sailed, heading for Blewfields, Jamaica. All four vessels met with disaster. The Hope of Boroughstomen leaked so badly, it had to be sold in Cartagena. The Company’s Hope missed Blewfields and was wrecked on the rocks called Colorados off the west end of Cuba. The Rising Sun reached Blewfields then struggled on to Charles Town in Carolina where, on August 24, 1700, it anchored about 9 miles from the harbor on a sand bar. Two week later, the ship was lost to a hurricane together with all hands, 112 passengers and Captain James Gibson. The Duke of Hamilton also went down in the same storm, but the crew was saved for most were on shore.

The 1,200 members of this third expedition fared no better than those of the first two. On the outward voyage, 160 perished, 315 died during the brief stay in Darien, and after evacuating New Edinburgh, 250 died of diseases and, with a hasty ceremony, were thrown overboard. Another 100 or so died in Jamaica, and 112 were lost in the wreck of the Rising Sun. About 360 survivors were dispersed among the English settlements; fewer would return to Scotland.

What Happened to William Paterson

As for Paterson, he reached home from New York on December 19, 1699, too late to help save the third expedition. Yet, even after this third disaster, he refused to give up. Now, however, he could not convince anyone. The Crown’s investigation of the disaster lay most of the blame on the directors in Edinburgh. On March 25, 1707, the Parliament of Scotland’s last motions before its dissolution, was to reimburse the Darien subscribers for their losses and “to recommend Mr. William Paterson to her Majesty for his good services.” In 1714 an Act of Parliament of Great Britain granted Paterson an indemnity of several thousand pounds. He died in 1719 in his native land and is buried in Sweetheart Abbey.

The wreck of the Scots dream carried a heavy toll. The cost was horrendous, accounting for the loss of nearly 2000 souls, in the Darien and at sea. From the 14 ships that sailed from Scotland, 11 never returned. Should a traveler visit Caledonia Bay today, one would only see those indestructible remains the jungle could not eradicate. There is the berm of the moat that the Scots dug to defend Fort St. Andrew. Indians today pole their canoes in it, and have no idea or care, what it is. The actual fort built of wood, decay and vanished long ago. The place where it stood is covered by a dense palm grove and tropical foliage; among their roots, if anyone cares to disturb them, the bones of a thousand Scots might be found.

Image Credits:

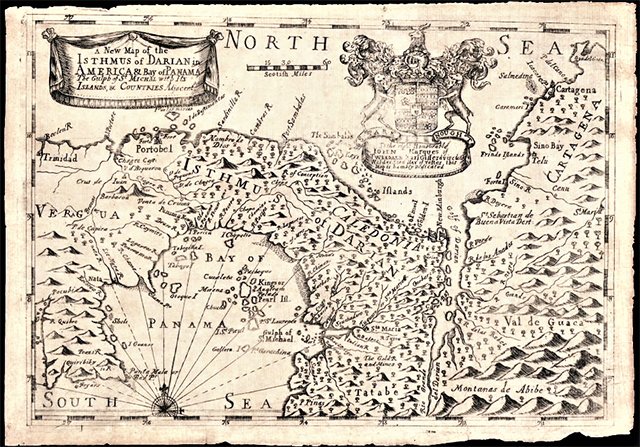

Graphic.1 – Map of the Isthmus of Darien, 1699 – Credit: Trustees of the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh

Graphic.2 – Ships of the East India Co. – Credit: in “The Disaster at Darien”, Russell Hart, Riverside Press, 1929

Graphic.3 – Toward the Unknown – Credit: artwork @ art-antiques-design.com

Graphic.4 – The Bay of Caledonia – Credit: Wikipedia.org, public domain

Graphic.5 – The Scots at Caledonia Bay – Credit: Wikipedia.org, public domain

Graphic.6 – A Short Lived Victory – Credit: artwork @ elgrancapitan.org

Graphic.7 – Return on Stormy Seas – Credit: Andy Simmons, 2004 @ ans.graphics.co.uk

References:

The Disaster of Darien – Francis Russell Hart, Riverside Press, 1929

Caribbean Sea of the New World – German Arciniegas, Knopf, 1946

Old Panama and Castilla del Oro – Dr. C. Anderson, North River, 1944

The Darien Disaster – John Prebble, Secker & Warburg, London, 1968

The People of Panama – John and Mavis Biesanz, Columbia Press, 1955

The Price of Scotland – Douglas Watt, Luath Press, Edimburgh, U.K., 2007

About the author:

Freelance writer, researcher and photographer, Georges Fery (georgefery.com) addresses topics, from history, culture, and beliefs to daily living of ancient and today’s communities of the Americas. His articles are published online at travelthruhistory.com, ancient-origins.net, popular-archaeology.com and in the quarterly magazine Ancient American (ancientamerican.com), as well as in the U.K. at mexicolore.co.uk. The author is a fellow of the Institute of Maya Studies instituteofmayastudies.org Miami, FL and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org. As well as member in good standing of the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org, the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org, the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. americanindian.si.edu, and the NFAA, Non-Fiction Authors Association nonfictionauthorsassociation.com.

Contact: Georges Fery – 5200 Keller Springs Road, Apt. 1511, Dallas, Texas 75248, (786) 501 9692 –gfery.43@gmail.com and www.georgefery.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.