by Bev Lundahl

As my companion and I wound through the forest and mountains of Vancouver Island from Nanaimo up to Port MacNeil, my thoughts kept returning to the mystery of what lay ahead. I was nearing the end of my journey from the prairies to Alert Bay on Cormorant Island, a short ferry ride from Port McNeill, British Columbia. And I was bringing with me the crest from HMCS Quesnel, the corvette my father had served on in World War Two. This crest had embroidered on it the image of a thunderbird totem, a totem that I had discovered originated from a burial ground at Alert Bay, British Columbia. Some of the crew had snatched this grave marker while on shore the summer of 1942 and it had become their mascot until the end of the war.

The ‘Namgis First Nation of the Kwakwaka’wakw people I was soon to meet were as mysterious to me as the symbolism of the thunderbird. To the veterans the totem was a lucky talisman but one of them thought it was a horned owl and another saw an eagle. An officer had wanted it removed from the ship because he considered it to be idol worship. When I mentioned its horns a friend suggested tufts was a better word because horns denoted evil. And finally the son of a Quesnel veteran writing about this badge described the image in part as a “multi-colored demon.” It seemed none of us really understood what the thunderbird represented.

Who were these people? Reading at the library of the First Nations University of Canada, I had learned that outsiders cannot decipher the markings on totem poles as if they were graphic or pictographic presentation of myth or history. They are visible expressions of a family history and of the possession of powers derived from their ancestors. The history had to be publicly recounted and witnessed and the erection of a pole was to be surrounded by ritual.

Who were these people? Reading at the library of the First Nations University of Canada, I had learned that outsiders cannot decipher the markings on totem poles as if they were graphic or pictographic presentation of myth or history. They are visible expressions of a family history and of the possession of powers derived from their ancestors. The history had to be publicly recounted and witnessed and the erection of a pole was to be surrounded by ritual.

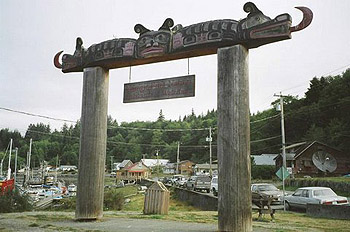

When we descended the ferry at Alert Bay I looked around with anticipation. An elaborate gateway (photo top) carved with “ ‘Namgis First Nation, Gilakas’la Welcome” greeted us. Down Front Street, which ran forever along the waterfront was the “Namgis Burial Grounds” (photo above) dotted with numerous totem poles interspersed with a few crosses to mark the graves.

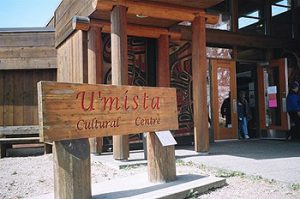

Walking further along Front Street we passed houses with people sitting out on the verandas carving masks and totems. The U’mista Cultural Center (photo at bottom) at the far end was situated beside the derelict remains of a faded brick residential school, that had closed some thirty years earlier. The old shop in the basement of the school was used as a workroom for carvers. (Photo left of Sean Whonnock)

Walking further along Front Street we passed houses with people sitting out on the verandas carving masks and totems. The U’mista Cultural Center (photo at bottom) at the far end was situated beside the derelict remains of a faded brick residential school, that had closed some thirty years earlier. The old shop in the basement of the school was used as a workroom for carvers. (Photo left of Sean Whonnock)

Inside the Cultural Center the history of the government’s banning of the potlatch was told in excerpts taken from Indian Affairs documents and displayed beside the ceremonial masks that had been confiscated by the authorities in the 1920’s and then returned over half a century later.

Up the hill in the Big House we learned more about their history and culture. There we watched the dancers (photo right) step to the beat of the music pounded out on a cedar log – dances that told of stories and legends through the use of masks and costume. It was a spectacular and moving sight, watching them circulate around a fire in the middle of the earthen floor.

Up the hill in the Big House we learned more about their history and culture. There we watched the dancers (photo right) step to the beat of the music pounded out on a cedar log – dances that told of stories and legends through the use of masks and costume. It was a spectacular and moving sight, watching them circulate around a fire in the middle of the earthen floor.

On the other side of the island a boardwalk led us on the eco-walk through the trees and marsh. As one gazed upward at the old defoliated trees, interspersed throughout the forest it wasn’t hard to see beaks and faces and wings – the inspiration for the totems that have been carved by these people for thousands of years – long before European contact.

Before retiring that evening to the Lodge, which was an old United Church that had been converted to a hostel, we watched the sunset from the waterfront deck of the Nimpkish Pub. Could this have been the same pub the sailors of sixty years ago had frequented? The orange glow of the sinking sun created burning steel gray shadows against the silver water, water that reflected the black, mountains in the background. Such a calm peaceful scene!

Prior to leaving this village I spent some time with Andrea Sanborn, the director of the Cultural Center and felt her pain regarding the theft of the grave marker of an Alert Bay family sixty years ago. The Navy newspaper “The Trident” quotes her as saying, “These stories need to be brought out in public, because not enough people really understand the history of First Nations people in this country”. In a quote in another newspaper she says “We would say that his spirit has been disturbed and that he is not at rest until it (the grave marker) is replaced”

Prior to leaving this village I spent some time with Andrea Sanborn, the director of the Cultural Center and felt her pain regarding the theft of the grave marker of an Alert Bay family sixty years ago. The Navy newspaper “The Trident” quotes her as saying, “These stories need to be brought out in public, because not enough people really understand the history of First Nations people in this country”. In a quote in another newspaper she says “We would say that his spirit has been disturbed and that he is not at rest until it (the grave marker) is replaced”

I did not learn the meaning of the markings on the thunderbird nor did I meet the family of Mr. Dutch, whose grave it had marked. I did learn something about our entangled histories but I believe this is only the surface. Because our country had a policy of segregation the mystery of this history can really only be learned through face to face contact and honest exchange. My trip to Alert Bay is only the beginning but it has opened my eyes and revealed another world out there. Alert Bay and the culture expressed there is beautiful but sadly the imprint of our intertwined history has left an indelible mark.

More Information:

U’mista Cultural Society

Village of Alert Bay, BC

To Get There:

Take the ferry from Tsawassen or Horseshoe Bay to Nanaimo B.C., then head up the Island Highway # 19 north from Nanaimo to Port McNeill. From there take the ferry to Alert Bay. Info: www.bcferries.com

About the author:

Bev Lundahl is a genealogist by nature thus most of her writing is historical, based on her research. She has been published in The Beaver magazine, Folklore Saskatchewan, The Heritage Gazette of Trent Valley (Ontario), Lifestyles (Estevan Sask.) and some of her research has been used on CBC Radio as well as in various Canadian newspapers. Bev lives in Regina, Saskatchewan.

Contact: bev.lundahl@accesscomm.ca.

Photo Credits:

All photos are by Bev Lundahl.

[…] mocha at the Culture Shock Gallery and walked along the waterfront to making our way over to the ʼNa̱mǥis Burial Ground where there are stands of totem poles. The totem poles ranged from those in final stages of […]