If there’s one thing that’s wholeheartedly true to the Australian spirit of independence, then it has to be the coolness of Australian beer. It’s not something that you discover in a heady rush over a single weekend! Instead, you will have to take the time to indulge in the beer, take a deep dive into the bubbling fantasy, and feel the beverage create its grasp. As the drink seeps into your system, you have to let your spirit wander in the hinterlands of Australia, from the urban lights to the overlapping aboriginal wilderness. If you are not suddenly feeling all macho to gulp down an entire crate, you might be missing out on the very point of drinking up in Australia!

Enjoy Your Evening in Leichhardt

While you try to decide from the bars in Leichhardt, settle for the one that sits upon the beverage and lets it take over the body without discomfort. Also, the bar should be able to offer an ample selection of choices between beers, wines, and cocktails. The Australian love for cocktails is not something that the rest of the world will understand! It’s quite embodied in the weather, the ambiance, the fun with friends, and the love for a tropical vacation. To feel a bit tipsy about it and to swirl in the thick, fruity flavors is something that an Australian will easily relate to.

Speaking of bars and night outs, the discussion usually veers again to beer drinking. Ever since Captain James Cook brought beer to the sun-burnt country, it has kept up its testament to the Aussie spirit of indulgence without spending over the top. To speak it bluntly, a typical Aussie guy would not care much about refinements and subtle etiquette. Instead, he will simply chug down a can of beer and be mates with everyone at the bar. Also, with the Aussie love for roasted food (such as barbecues and kebabs), beer conveniently fills in the gap in the taste buds.

Feel the Dizzy Drinking Fest

A good bar will maintain a diverse collection of beer from the strong ones to the light ales. Medium-strength beers are quite popular as you can swirl down a lot of them before you feel the dizziness hammering your head. Australian men love to binge out and shout (and maybe talk about kangaroos, spiders, and cricket). If there’s something that wholeheartedly applies to this spirit of heavy partying, it’s got to be your favorite beer.

That said, wine is also a quite popular drink in Australia. Also, other types, such as whiskey, rum, gin, and vodka, have their fair share of appreciation. However, overall, an Aussie will always pick up beer as the first choice and then maybe think about other stuff. Even when Aussies drink wine, it’s always loud and lively, not giving a damn about the whiffs and halos. You should be able to discover this fun-loving spirit in most bars in Leichhardt. So, you should just take your time, tag your mates, and let yourself drown in the thick, dizzy drain-out of drinks that got you in the first place.

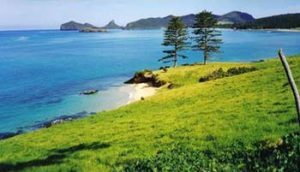

Photo credit:

Thorby Buildings, Leichhardt by RosieWylie, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons